節足動物

| 節足動物 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

現生および絶滅した様々な節足動物[注釈 1]

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 地質時代 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| カンブリア紀 - 現世 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Arthropoda Gravenhorst, 1843[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 和名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 節足動物 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 英名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Arthropod | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 亜門 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

絶滅群は本文参照 |

節足動物(せっそくどうぶつ、英語: Arthropod、学名: Arthropoda[3])とは、昆虫・甲殻類・クモ・ムカデなど、外骨格と関節を持つ動物を含んだ分類群。分類学上は節足動物門とされる。動物界最大かつ多様性の最も高い動物門であり[4][1][5][6]、現生種は全動物種の85%以上を占め、約110万種が記載されている[7]。陸・海・空・土中・寄生などあらゆる場所に進出し、様々な生態系と深く関わっている。なお、いわゆる「虫」の範疇に入る動物は当動物門のものが多い[注釈 2]。

学名 Arthropoda はギリシア語の ἄρθρον(arthron, 関節)と πούς(pous, 脚)の合成語であり、本動物門の関節に分かれた付属肢(関節肢)にちなんで名づけられた[8]。

形態学、解剖学と生理学[編集]

節足動物の形態は多様で、種類により様々な外見を持つ。現生種の大きさは1mm未満のダニから数10 cmのロブスターまで幅広く、古生物にまで範囲を広げると2m以上と考えられる巨大な種類も含まれる[9][10][11]。体の表皮はキチン質とタンパク質等からなるクチクラ(cuticle)で、外骨格(exoskeleton, sclerite)と関節(articulation)を構成する。これは成長につれて更新されていき、古い表皮は脱皮により脱ぎ捨てられる[12]。

体節制[編集]

節足動物は体節制(segmentation)をもつ。すなわち、体は体節(somite)という単位の繰り返し構造からなり、各体節は原則として1対の付属肢をもつ(後述)[13]。体は原則として上下が背板(tergite, tergum)と腹板(sternite, sternum)に覆われており、更に左右に側板(pleuron)を持つものもある。これらの外骨格も体節単位になっており、体節の間は関節に分かれて可動であることが多い。体の先頭の体節は先節(ocular somite)といい、節足動物の眼と口はここに由来する[14]。体の末端に尾節(telson)という非体節性の尾に相当する構造をもつ場合もある[13]。

ただし、節足動物は異規体節制(heteronomous metamerism[15])がある程度発達し、複数の体節が組み合わされ、合体節(tagma)という外観上あるいは機能上の単位を構成する(節融合、tagmosis, tagmatization)例が多く見られる[16][13]。例えば、体を「頭部 (head, cephalon)・胴部 (trunk)」、「頭胸部 (cephalothorax)・腹部 (abdomen)」、「前体 (prosoma)・後体 (opisthosoma)」などの2部、または「頭部・胸部 (thorax)・腹部」、「頭部・胸部・尾部 (pygidium)」、「前体・中体 (mesosoma)・終体 (metasoma)」などの3部に分けて呼ぶ場合があり、これは節足動物の各分類群ごとの特徴として用いられる[13]。特に前方の合体節(頭部融合節 head tagma, 頭部・前体など)は往々にして体節の癒合が進み、外見上では元の体節構造が見当たらず、すべて単一の外骨格に覆われている[13]。一方、体節の融合や退化が極端に進み、外見上の体節構造が全く見当たらない例もある[13]。

付属肢[編集]

節足動物の各体節からは、原則として1対の関節肢(arthropodized appendage)という本群に特有の付属肢が出ている。これが「節足動物」という名前およびその学名の由来となっている[8]。関節肢も体節と同様に外骨格で覆われ、関節によって分かれた肢節(podomere)からなる。これは分類群や位置により歩脚・遊泳脚・鋏・鎌・顎・触角・鰓・生殖肢など様々な機能に応じて様々な形に特化している[13]。例えば頭部には感覚用の触角と摂食用の顎、胴部には移動用の歩脚を持つなど、節足動物は、往々にして異なる機能を担った様々な関節肢を兼ね備え、「アーミーナイフのように、別々の機能をもつ複数の道具が同時にセットされる」とも比喩される[17]。また、節足動物は多くが口の直前に上唇(labrum)やハイポストーマ(hypostome)などという1枚の蓋状の構造体があり、これも付属肢由来の部分ではないかと考えられる[18][19][20][14]。なお、前述の体節のように、関節肢が不明瞭もしくは完全に退化消失した例もある[13]。

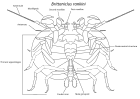

A: バッタ、B: ハチ、C: チョウ、D: カ、a: 触角、c: 複眼、lb: 上唇、lr: 下唇、md: 大顎、mx: 小顎

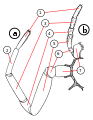

節足動物の関節肢は、全長が枝分かれしていない単枝型付属肢(単肢型付属肢、uniramous appendage)、もしくは内側の内肢(endopod, endopodite)と外側の外肢(exopod, exopodite)に枝分かれした二叉型付属肢(二肢型付属肢、biramous appendage)で現れる。多くの現生節足動物(六脚類・多足類・ほとんどの鋏角類)は単枝型付属肢のみをもつが、甲殻類[21]や三葉虫・メガケイラ類などの古生代の絶滅群では二叉型付属肢の方が一般的である[22][23]。それ以外にも、外側に外葉(exite, 副肢 epipod, epipodite)、内側に内葉(endite, 内突起)などという非肢節性な分岐をもつものがある[23]。

-

カマキリの鎌状の前脚

運動[編集]

節足動物の外骨格は分節した関節と、その間にある柔らかい節間膜(arthrodial membrane)により可動域を得られている。分節した体節は関節が伸縮から湾曲まで、様々な方向に動かせる場合が多いが、関節肢の関節は往々にして1つか1対の関節丘(condyle)により外骨格の支点を固定され、特に1対の場合では軸や蝶番のように1つの平面上で安定に折り曲げる[24][25][26]。そのため節足動物の関節肢、特に基部は往々にして複数の関節に分かれ、様々な動きに対応するようになっている[24][25][27][28]。外骨格の関節の摩擦を抑えるように、それに隣接した外骨格の縁辺部から潤滑物質を分泌することも知られている[29]。

また、節足動物の運動機構は往々にして上述の外骨格のみならず、体内の筋肉に付着面を提供する内骨格(endoskeleton)も兼ね備えている。これは主に外骨格の内壁から伸長したもの、もしくは筋肉の付け根から硬化した腱(内突起、internal tendon, apodeme)である[31]。例えばほとんどの節足動物は、付属肢基部の外在筋に繋がる内腹板(endosternite, 内腹甲[32])を体節内にもつ[31][33][34][30]。カニなどの強力な挟む力をもつ鋏の中には、可動指内側の関節に繋がった、大量の屈筋とそれに付着する板状の腱が見られる[35][36][37]。

また、筋肉以外の機構で関節を動かす例も多く見られる。例えば多くのクモガタ類は脚の途中の関節に伸筋を持たず、体内の血リンパ(後述)の水圧(クモなど)、もしくは弾性のある特殊な外骨格(ヒヨケムシなど)で関節を広げて脚を伸ばす[25][38][39][30]。

他の内部構造[編集]

赤:心臓、黄:消化管、青:中枢神経

他の多くの左右相称動物と同様、節足動物は体腔を持ち、消化系は体の前後を貫通し、いわゆる口と肛門という2つ開口を持つ。心臓は体腔の背面に、脳以外の中枢神経系は体腔の腹面に付属する。

消化系と排出器[編集]

消化管は往々にして順に咽頭(pharynx)・食道(esophagus)・前腸(foregut, 前胃 proventriculus)・中腸(midgut)・後腸(hindgut)などと分かれるように分化が進み、発達した分岐(diverticula, 消化腺 digestive gland, 中腸腺 midgut gland)を中腸にもつ場合もある[40]。消化管の前後、いわゆる口と肛門のすぐ内側の内壁はクチクラ性で、成長の際には外部の表皮と同様に脱皮して更新される[41]。

基本的な排出器として対になる腎管(nephridium)がある。これは分類群ごとに特定の付属肢基部で開口することにより、触角腺(antennal gland, 甲殻類の第2触角)[42]・小顎腺(maxillary gland, 甲殻類の第2小顎)[43]・基節腺(coxal gland, 鋏角類の脚)[44]などと呼ばれている。それ以外の排出器としては消化管から枝分かれたマルピーギ管(malpighian tubule)があり、六脚類、多足類とクモガタ類に見られる[45][46][47]。

循環系[編集]

節足動物の循環系は基本として開放血管系(open circulatory system)であり、細胞外液はリンパ液や血液という区別はなく、リンパ液と血液の役割を兼ねた血リンパ(hemolymph)が背面の心臓と組織の間隙(血体腔)に流れている[48]。心臓の伸縮や体の運動により、血リンパは心臓の動脈から体の静脈や呼吸器などの器官を通り、心門を介して再び心臓に戻る。血リンパの中には免疫系の血球(hemocyte)がある[49]。心臓は消化管の背面にあり、基本では体長の大部分を占めるほど縦長いが、カニやミジンコのように一ヶ所に集中する例もある[50]。

神経系[編集]

体節制をもつ他の前口動物に似て、節足動物の中枢神経系の様式ははしご形神経系(ladder-like nervous system)である。前背面の脳(後述)の直後に続く腹面1対の腹神経索(腹髄神経索、ventral nerve cord)は体節ごとに神経節(ganglion)となって左右の連絡(横連合 commissure)で繋がり、全体的はしご形となっている。ただし、神経節が集中してはしご形が不明瞭な場合もあり、例えばカブトガニやクモガタ類の前体において脳と腹神経索を集約させた synganglion、およびカニや派生的な昆虫において著しく集約した胸部と腹部の神経節がその例である[51]。

神経系の前端部には脳があり、食道の前上方にあることから食道上神経節(supraoesophageal ganglion, 大脳神経節[52])とも呼ぶ。現生の節足動物では、これは先頭3つの体節(先節・第1体節・第2体節)がもつ3対の神経節の融合でできた脳(tripartite brain)であり、前大脳(protocerebrum)・中大脳(deutocerebrum)・後大脳(tritocerebrum)という3つの脳神経節(cerebral ganglion)から構成される[53][20][54][14][55]。前大脳には複眼からの視覚情報を処理する視葉(optic lobe)、嗅覚の識別や記憶および感覚神経の統御を司るキノコ体(mushroom body)、視覚行動の統御を行う中心複合体(central body)を持つ[54]。脳は前大脳をはじめとして背側にあるため、中央もしくは直後から食道を囲み、食道神経環(circumesophageal nerve ring)を介して腹面の腹神経索に連結する。昆虫・甲殻類などの大顎類の場合、食道神経環の直後は顎(大顎・小顎/下唇)に対応する神経節で、まとめて食道下神経節(suboesophageal ganglion、顎神経節[52])といい[54]、ハエやハチ、チョウなどにおいては脳と融合し頭部神経節を構成する(この場合は食道上神経節のみならず、食道下神経節も脳の一部と扱う)[54]。

感覚器[編集]

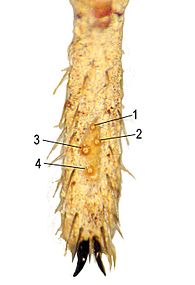

節足動物は様々な感覚器を通じて周りの環境を感知する。体表は常に剛毛(刺毛、感覚毛、seta, 複: setae)をもち、種類により触覚・振動・音・水流・気流・温度・嗅覚・味覚・化学物質など視力以外の感覚を担う。中で振動を感知するのに特化したものは聴毛(trichobothrium, 複: trichobothria)と呼ぶ[56]。

鋏角類以外の節足動物の頭部は、往々にして触角(antenna, 複: antennae)という関節肢をもち、ほとんどの場合は重要な感覚器である。なお、触角をもたない鋏角類の中でも、ウデムシやサソリモドキのように、一部の脚が触角状の感覚器に特化した例がある[25][57]。

他にも昆虫の小顎と下唇にある顎鬚(palp)が嗅覚や味覚に関わり、一部の昆虫と甲殻類の後端にある尾毛(cercus, caudal ramus)も感覚器官として用いられる[58]。サソリの櫛状板(pectine)とヒヨケムシのラケット器官(malleoi)は各群に特有の感覚器であり[57][59]、一部の昆虫は特定の部分(例えばコオロギやキリギリスの前脚脛節[60]・バッタの腹部[61]・カマキリの後胸部腹面[62])に特化した聴覚器官である鼓膜器官(tympanal organ)をもつ[63]。

-

感覚用の第1脚をもつウデムシ

眼[編集]

節足動物は、中眼(median eye)と側眼(lateral eye)という先節由来[14]の2種類の眼を兼ね備え、その中で中眼は単眼(ocellus, simple eye)、側眼は複眼(compound eye)であることが基本と思われる[64][65][66]。しかしその片方しか持たず、複眼が単眼(側単眼)に変化し、または眼が完全に退化消失した例もある。

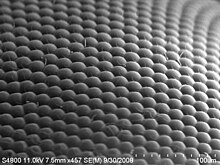

複眼は図形認識能力をもち、数多くの個眼(ommatidium)というレンズ様の構成単位からモザイク画のような視覚を形成する。単眼は主に明暗を感知するなど補助的な機能を担うが、一部のクモ(ハエトリグモ、メダマグモなど)のように単眼が優れた視力をもつ例もある[39]。

眼をもつ節足動物の中で、六脚類と甲殻類は基本的に中眼と側眼を兼ね備える。後者の場合、中眼はノープリウス幼生期のノープリウス眼に当たる[64]。多足類は全て中眼をもたず、中でゲジ類のムカデは側眼が複眼のままで、他のムカデとヤスデは複眼由来の側単眼をもつ。鋏角類の中でウミグモは中眼のみ、カブトガニとウミサソリは複眼と中眼の両方、現生のクモガタ類は複眼を持たず、中眼と複眼由来の単眼を兼ね備えるか片方のみを持つ[65]。また、古生代の三葉虫やラディオドンタ類をはじめとして、化石種のみ知られる絶滅群も多くが発達した複眼を有し[67][68]、中眼をもつことが認められるものもある[69][66]。

呼吸[編集]

節足動物は様々な生息環境に進出しており、それに応じた多様な呼吸様式がみられる。水中呼吸の水生種では鰓(gill)、空気呼吸の陸生種では気管系(tracheal system)や書肺(book lung)などをもつものがあり、気管系と書肺は気門(spiracle, stigma)を介して空気を出入りする。呼吸器は特に持たず、体表で直接的に皮膚呼吸を行う種類もある。

- 六脚類は主に陸生で発達した気管を持ち、胸部と腹部のほとんどの体節に一対の気門を持つ[70]。一部の水生昆虫の幼虫は、気門の代わりに水中呼吸用の気管鰓(tracheal gill)を持つ[71]。不均翅亜目のトンボの幼虫(ヤゴ)は、鰓に特化した直腸内側の皺状突起(rectal gill)で水中呼吸する[72]。

- 多足類は全て陸上性で、呼吸器をもたないエダヒゲムシ以外[73]では六脚類と似たような気管と気門で呼吸する。気門の位置は分類群によって異なり、ゲジ類のムカデ(背気門類)は発達した背板ごとに背面1つ[74]、他のムカデ(側気門類)は1-2胴節につき左右1対、ヤスデは1体環につき両腹面2対[73]、コムカデは頭部に1対もつ[75]。

- 鋏角類の中で、陸生のクモガタ類は主に書肺や気管系、水生のカブトガニ類は可動な蓋板に付属した書鰓(book gill)で呼吸する[57]。なお、ウミグモ、コヨリムシと一部のダニは呼吸器を持たず、皮膚呼吸を行う[76][10]。

- 甲殻類は多くが水生で、通常では付属肢基部の外葉(副肢)が鰓となって水中呼吸をする[21]。陸生等脚類(ワラジムシ亜目)は腹肢の白体(pleopodal lung, 偽気管 pseudotrachae)で空気呼吸する[77][78]。陸生十脚類は元々水中呼吸用だった鰓が空気呼吸に特化し、特にヤシガニなどの陸生ヤドカリ類は空気呼吸用の二次的な突起物も兼ね備えている[79]。

繁殖と発育[編集]

求愛・包接・メイトガード・交尾・交接・護卵・育児など、節足動物は分類群により様々な繁殖行動を持つ。原則として有性生殖を行う卵生動物であるが、単為生殖や卵胎生を行う例も知られている。例えばアブラムシとサソリの雌親は幼生を産み、ミジンコは環境に応じて単為生殖と有性生殖を切り替える[80]。

節足動物の幼生は基本的に成体と似たような外見を持つが、かけ離れた姿で生まれ、成長するたびに著しく形態が変化する変態(metamorphosis)を行う分類群も少なくない。甲殻類のノープリウス幼生から始まる生活環、昆虫の完全変態(holometabolism, 幼虫と蛹を経て成虫になる)、および多足類の増節変態(anamorphosis, 成長するたびに体節が増える[81][82])がその例である。

成長するたびに、外骨格を含めて節足動物のクチクラはそれと共に大きくならず、代わりに既存のクチクラの下で柔軟な新しいクチクラを形成し、古いクチクラを抜き捨ててから新しいクチクラが膨らんで大きくなる。この過程は脱皮(ecdysis)といい、昆虫の場合は特定の成長過程を指すのに蛹化(終齢幼虫から蛹になる脱皮)や羽化(成虫になる最終脱皮)とも呼ばれる。ただし新しいクチクラの外骨格は柔らかく、元の硬さになるまで時間も掛かるため、脱皮中や脱皮直後の節足動物は普段より無防備で、外骨格が硬くなるまで主に体内の水圧や空気で体の形を整っている[12]。そのため節足動物の脱皮は、捕食者が少ない時間帯や巣穴などの隠れ場所で行うことが多く、例えばセミは夜中で羽化し[83]、一部の昆虫の幼虫とヤスデは脱皮前に繭を作る[84]。また、成分を回収するように古いクチクラを摂食する種類や、脱皮直後の配偶の無防備さを利して繁殖行動をする種類も知られている[39]。

他の動物門との関係[編集]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 左右相称動物における節足動物の系統的位置 |

節足動物と他の動物門の類縁関係は長らく議論をなされ、20世紀末と2000年代を介して劇的に更新された[85][86][20][87][4]。21世紀以前では、前口動物で体節制を持つなどの共通点から、節足動物と環形動物は近縁である同時に、舌形動物(シタムシ)・有爪動物(カギムシ)・緩歩動物(クマムシ)という3つの動物門は、両者の中間形態を示唆するという考えが主流であった。これらの動物群は、体節動物(Articulata[88])という単系統群を構成すると考えられ[89][90][91][92]、中でも有爪動物と緩歩動物は節足動物に内包され[3][93]、もしくは舌形動物・有爪動物・緩歩動物がまとめて側節足動物(Parathropoda[94])として区別される経緯すらあった[95]。

しかし21世紀以降では、分子系統学をはじめとする多方面(遺伝子発現・解剖学・発生学)な進展により、環形動物は他の体節動物に類縁でなく、むしろトロコフォア幼生を共有する軟体動物などと共に単系統群の冠輪動物(Lophotrochozoa)に属するものであると判明した。同時に他の体節動物も環形動物より、むしろ脱皮などの性質を共有する線形動物などと単系統群になると判明し、脱皮動物(Ecdysozoa[96])として区別されるようになった[97][85][86][87][4]。かつて体節動物の根拠とされてきた環形動物と他の体節動物の体節制も、後に発生学と遺伝子発現の違いにより別起源(収斂進化)であることが示唆される[98][99][100]。更に、かつて側節足動物ともされてきた群の中で、緩歩動物と有爪動物は節足動物に内包されない独立の動物門として広く認められる一方、舌形動物は独立した動物門ではなく、鰓尾類に近縁の甲殻類、すなわち極端に特化した節足動物の一員だと判明した[101][102][4]。

その結果、古典的な「体節動物」と「側節足動物」はいずれも系統関係を反映できない多系統群として解体され、徐々に21世紀以降の分類体系から廃止された[87][4]。21世紀、特に2000年代後期以降では、脱皮動物の中で、節足動物・有爪動物・緩歩動物という3動物門が単系統群を構成する説が広く認められ、まとめて汎節足動物(Panarthropoda[103])と呼ばれている[104][105][106][4]。

なお、脱皮動物と汎節足動物の単系統性が広く認められるものの、汎節足動物と他の脱皮動物(環神経動物 Cycloneuralia[107][108])の系統関係ははっきりしておらず、汎節足動物内の3動物門は形態の類似と分子系統解析の食い違いにより、お互いの系統関係は諸説に分かれている[109]。これらの議論の詳細については汎節足動物#系統関係および汎節足動物#内部系統関係を参照のこと。

起源[編集]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 節足動物の初期系統を中心とする汎節足動物の内部系統関係[110] †:絶滅群、青枠:基盤的な節足動物、*:葉足動物 |

知られる最古の節足動物は、およそ5億年前のカンブリア紀に遡る[1]。この地質時代からは、アノマロカリスとオパビニアをはじめとするラディオドンタ類(アノマロカリス類)やオパビニア類など、節足動物的性質と節足動物らしからぬ性質を兼ね備える古生物が見つかり、節足動物の絶滅した基部系統(ステムグループ)を表したものとして広く注目される(後述)[111][112][113][114][4][115]。しかし、派生的な節足動物の知られる最古の化石記録はそれ以上に早期(体の化石は約5億2,100万年前まで、生痕化石は約5億3,700万年前まで)のため、節足動物の基部系統は中間的な化石記録を欠いており、実際の起源は記録以上に古かったことが示唆される[1]。なお、カンブリア紀とその直前のエディアカラ紀の化石産地の比較により、その起源は、エディアカラ紀晩期(約5億5,000万年前)より古くはなかったと考えられる[1]。

節足動物の基部系統に含まれる古生物、いわゆる基盤的な節足動物(ステム節足動物 stem-arthropods, ステムグループ節足動物 stem-group arthropods)は、主にラディオドンタ類、オパビニア類、シベリオン類、およびこれらの古生物の特徴を掛け合わせたようなケリグマケラとパンブデルリオンがある。これらの古生物は特化した先頭1対の前部付属肢が特徴的で[20][14]、体の両筋に鰭をもつ種類は恐蟹類(dinocaridids, Dinocaridida)、パンブデルリオンとケリグマケラは便宜的に「gilled lobopodians」としてまとめられる場合もある[116][117]。

これらの古生物は胴部が柔軟で口器も放射状であり、一見では節足動物らしくないが、ある程度の節足動物的性質をもつことが分かる[20][14]。いずれも早期の節足動物において特徴的な消化腺をもち[40]、特にラディオドンタ類は最も節足動物的で、関節肢・複眼・背面の外骨格(背板)などという節足動物として決定的な特徴が頭部に出揃っている[20][14][64][4]。オパビニア類は節足動物に似た後ろ向きの口と分化した眼を有し[20][14][110][118]、ラディオドンタ類やパンブデルリオンに見られる背腹2種類の付属肢構成(背側の鰓/鰭と腹側の鰭/脚)も、節足動物の外葉と内肢を兼ね備える二叉型付属肢を彷彿とさせる[111][114]。

一方、シベリオン類は姿そのものがれっきとした葉足動物(脚のある蠕虫様の化石汎節足動物)であり、パンブデルリオンとケリグマケラも葉足動物に似た表皮構造と付属肢(葉足)をもつ[111]。このような中間型生物の存在により、汎節足動物の中で、節足動物は有爪動物や緩歩動物と同様、葉足動物から派生した動物群であることが示唆される[20][14][1]。また、ラディオドンタ類とオパビニア類の複合的な性質により、節足動物の体節構造・複眼・頭部外骨格・関節肢(arthropodization)は、後大脳と胴部外骨格(arthrodization)より早期に進化し、基部系統で既に出揃ったことも示される[20][14][4][118][66]。

基盤的な節足動物より派生的で、現生群をも含んだ残り全ての節足動物は一般に真節足動物[16](Euarthropoda, または Deuteropoda)として区別される[20][14][66]。この系統群をはじめとする節足動物は、頭部は後大脳をもつ体節まで融合した合体節で、胴部まで外骨格と関節肢を備わっており、前述の基盤的な節足動物とは明らかに異なる[20][14]が、キリンシアなどという、基盤的な節足動物に似た特徴が顕著に見られる中間型生物もある[110]。他にはイソキシス類(イソキシス、スルシカリス)・メガケイラ類(レアンコイリア、ヨホイアなど)・フーシェンフイア類・Hymenocarina類(ワプティア、カナダスピスなど)が挙げられており、これらは文献や種類により現生節足動物の系統群(鋏角類・多足類・甲殻類・六脚類)全体よりも基盤的[14][20]、もしくは特定の現生群の基部系統に属すると考えられる(後述)[4][115][110]。

分類[編集]

系統関係と体節の相同性[編集]

現生の節足動物は、鋏角類(Chelicerata, クモ、サソリ、カブトガニなど)・多足類(Myriapoda, ムカデ、ヤスデなど)・甲殻類(Crustacea, カニとエビ、フジツボ、ミジンコなど)・六脚類(Hexapoda, 昆虫、トビムシなど)という4つの亜門に分類されている。化石種まで範囲を広げれば、三葉虫などを含んだ Artiopoda という過去の亜門や、前述の亜門には明確に収まらない分類群も数多く知られている(後述参照)[4][115]。

それそれの分類群で特に注目される特徴は、先頭複数体節の融合でできた合体節(頭部および前体)の付属肢である。これは前述のような高次分類群によって異なり、例えば各亜門では次のような既形をもつ[6][14][57]:

- 六脚類:触角1対・大顎1対・小顎1対・下唇1枚(1対の小顎から癒合した部分)

- 多足類:触角1対・大顎1対・小顎2対

- 甲殻類:触角2対・大顎1対・小顎2対

- 鋏角類(真鋏角類):鋏角1対・触肢1対・脚4対

- 鋏角類(ウミグモ類):鋏肢1対・触肢1対・担卵肢1対・脚1対

- Artiopoda類:触角1対・脚3対以上

これらの付属肢の由来と対応関係(相同性)は、節足動物の各分類群の系統関係を示唆する重要な指標の1つであるが、分類群ごとの形態の違いや化石群の証拠の欠如により難解な場合が多く、この問題は「Arthropod head problem」として知られている[14][4]。それに対しては「終わりのない論争」(endless dispute)とも呼ばれるほど、昔今を通じて文献記載により様々な解釈を与えられた[119][14]。

21世紀以前の古典的な見解では、鋏角類は中大脳性な触角を退化して鋏角は後大脳性と考えられ[120]、頭部付属肢や呼吸器の類似を基に多足類と六脚類は近縁という説が主流であり[16][121]、付属肢の単枝型と二叉型の基本形態を基に、節足動物を多系統群として2つに分けるという異説すらあった。しかしこれらの知見は、後に発生学・神経解剖学・遺伝子発現・分子系統学など多方面の情報により根本から否定され、節足動物は疑いなく単系統群・鋏角類の鋏角は他の節足動物の第1触角と同様に中大脳性[122][123][124][125]・六脚類は甲殻類に近縁で側系統群の甲殻類から分岐したことが強く示唆される[126][127][128][129][130][131][132]。また、通常では鋏角類とされるウミグモ類の系統位置がしばしば疑問視されるようになり、分子系統解析では鋏角類であることを支持するものが多い[133][134][115]が、2000年代ではそれ以外の節足動物と対置すべき説もあった[135][129][136]。

三葉虫やメガケイラ類をはじめとして、幾つかの化石節足動物の分類群と現生分類群の類縁関係については、未だに定説がない[4]。例えば三葉虫などを含む Artiopoda類は、鋏角類に類縁という伝統的な系統仮説はあった[120]が、頭部構造の類似に基づいて触角をもつ現生群(多足類・甲殻類・六脚類)に近い[137][138][139]、またはどの現生群よりも基盤的[140]とも考えられる[4]。メガケイラ類は先頭の付属肢と脳の類似に基づいて鋏角類に近いとされる[141]が、どの現生群よりも基盤的ともされる[20][14][4]。Hymenocarina類は一時では単調な頭部をもつと解釈され、それを基にどの現生群よりも基盤的と考えられていた[20][14]が、大顎をもつ口器の発見により、多足類・甲殻類・六脚類と同じ系統群に含める説が主流になりつつある[140][142][4][115]。

こうした研究の発展に伴い、節足動物の高次系統に対して様々な系統仮説が提唱されており、以下の例が挙げられる[143][144]。

- 大顎類 Mandibulata

- 現生群では多足類・甲殻類・六脚類からなる。大顎が共有形質とされる。

- 汎甲殻類 Pancrustacea(=八分錘類 Tetraconata)

- 現生群では甲殻類と六脚類からなる。複眼の八分割される硝子体などが共有形質とされる。

- 多足鋏角類 Myriochelata(=矛盾足類 Paradoxopoda)

- 多足類と鋏角類からなる。

- 裂肢類 Schizoramia(='CCT' clade)

- 甲殻類・鋏角類・Artiopoda類などからなる。ニ叉型付属肢が共有形質とされる[145]。

- 無角類 Atelocerata(=気門類 Tracheata、狭義の単肢類 Uniramia sensu stricto)

- 現生群では多足類と六脚類からなる。後大脳性/第2体節付属肢の欠如・気門などが共有形質とされる。

- 広義の単肢類 Uniramia sensu lato

- 有爪動物・多足類・六脚類からなる。単枝型付属肢が共有形質とされる。またこの系統仮説に従えば、有爪動物は節足動物に含まれ、もしくは節足動物が有爪動物に対して多系統群になる[16]。

- Arachnomorpha(=蛛形様類 Arachnata[146])

- Artiopoda類と鋏角類からなる。

- Antennulata

- Artiopoda類・多足類・甲殻類・六脚類などからなる。中大脳性/第1体節由来の第1触角が共有形質とされる。

- 板肢類 Lamellipedia[145][146]

- Artiopoda類と Marrellomorpha類からなる。

2010年代以降では、少なくとも大顎類説、汎甲殻類説、およびウミグモ類が鋏角類に含める説が広く認められる[4][115]。

| 節足動物の内部系統関係 |

| 節足動物の各亜門(太字)の類縁関係とそれぞれの主要な内部高次系統までの分岐図[4][115]。青枠以内の分類群、すなわち六脚類以外の汎甲殻類は側系統の甲殻類に属する。絶滅群は「†」、類縁関係が議論的なもの(鋏角類とArtiopoda類と大顎類、貝形虫類とヒゲエビ類とウオヤドリエビ類、軟甲類と鞘甲類とカイアシ類)は3本以上の多分岐、単系統性が議論的なもの(節口類、クモガタ類、内顎類)は二重線で示される。亜門が未定・不確実、もしくはそのクラウングループに含まれない絶滅群、およびほとんどの系統解析に含まれないヒメヤドリエビ類はここに示さない。 |

また、現生節足動物の胚発生において、眼と前大脳が由来する先頭の体節、いわゆる先節には付属肢を持たないのが従来の解釈であった。しかし、多くの節足動物の口の前にある蓋状の構造体、いわゆる上唇やハイポストーマは、著しく融合・退化した先節由来の1対の付属肢であることが2000年代以降から有力視されつつある[18][19]。この構造体は、有爪動物の触角や基盤的な節足動物(ラディオドンタ類など)の前部付属肢との相同性まで議論をなされ、初期の節足動物、果ては汎節足動物全般における頭部の起源と進化を示唆する手掛かりの一つとして注目される[113][20][14]。

下位分類[編集]

節足動物は記載された種数の最も多い動物門である[1][5][6]。その数は動物に限らず、真核生物の種の大部分をも占める[5][147]。2011年まででは、100万種以上の六脚類・11万種以上の鋏角類・6万種以上の甲殻類・1万種以上の多足類という計120万種以上の現生節足動物が記載されている[148][6]。また、絶滅した三葉虫も大きなグループであり、1万種以上が記載される[149]。

節足動物の主要な高次分類群(綱/亜綱/目)までの下位分類は次の通り。なお、これらは必ずしも2010年代後期以降の主流な系統関係を反映しているとは限らず(例えば甲殻類は六脚類に対して側系統)、分類階級が文献により異なる(鞘甲類・カイアシ類など)・単系統性に議論が続いているものもある(節口類・クモガタ類・六幼生類・内顎類など)[4]。

- 甲殻亜門 Crustacea(側系統群)

- 貝形虫綱 Ostracoda - 貝虫(カイミジンコ、ウミホタルなど)

- ヒゲエビ亜綱[153] Mystacocarida - ヒゲエビ

- ウオヤドリエビ綱[153](イクチオストラカ綱[154]) Ichthyostraca

- 鰓尾亜綱 Branchiura - 鰓尾類(チョウ/ウオジラミなど)

- 舌形亜綱 Pentastomida - シタムシ

- 軟甲綱 Malacostraca - シャコ、カニ、エビ、オキアミ、ダンゴムシなど

- 六幼生綱[153](六齢ノープリウス綱[154]) Hexanauplia

- 鰓脚綱 Branchiopoda - アルテミア、ホウネンエビ、カブトエビ、カイエビ、ミジンコなど

- カシラエビ綱 Cephalocarida - カシラエビ

- ムカデエビ綱 Remipedia - ムカデエビ

-

様々な昆虫

絶滅した分類群[編集]

以下は上記の現存群(鋏角類・多足類・甲殻類・六脚類)のクラウングループに含まれていない(例えば該当現存群に対して基盤的な化石分類群、ステムグループ)、もしくは所属する現存群が不確実な化石分類群を列挙する。

- ラディオドンタ目(放射歯目)Radiodonta - ラディオドンタ類[156][157][158][159](放射歯類[151]、広義のアノマロカリス類[160][161])。アノマロカリス、アンプレクトベルア、ペイトイア、フルディアなど。

-

様々なラディオドンタ類

- (目)Hymenocarina[140]

- カナダスピス、ブランキオカリス、オダライア、ワプティアなど。真節足動物[163][164][22]/大顎類[140][142][165][110][166][167][162]/汎甲殻類[142][168][169]のいずれかのステムグループ。カンブリア紀に生息。

- フーシェンフイア目 Fuxianhuiida[22]

- フーシェンフイア類。フーシェンフイア、チェンジャンゴカリスなど。真節足動物[163][164][20][22]/大顎類[140][142][110]のいずれかのステムグループ。カンブリア紀に生息。

- メガケイラ綱 Megacheira[145]

- メガケイラ類[156](大付属肢節足動物、大付属肢型節足動物)。ヨホイア、ハイコウカリス、レアンコイリア、フォルティフォルケプスなど。真節足動物[20][22][170][169][165]/鋏角類[141][110][162][66]のいずれかのステムグループ。カンブリア紀( - デボン紀?)に生息。

-

インディアナ(化石)

- (目)Phosphatocopina

- Hesslandona、Vestrogothia など。大顎類のステムグループ[164]もしくは甲殻類[172]。カンブリア紀に生息。

- マーレロモルフ綱 Marrellomorpha

- マーレロモルフ類[156][158](マレロモルフ類[159])。マーレラ、ヴァコシニア、フルカ、ミメタスターなど。真節足動物[140]/大顎類[164][170]のいずれかのステムグループ。カンブリア紀 - デボン紀に生息。

- ユーシカルシノイド綱 Euthycarcinoidea

- ユーシカルシノイド類[156]。ユーシカルシヌス、ヘテロクラニア、アパンクラなど。大顎類[140]/多足類[173]のいずれかのステムグループ。カンブリア紀 - 三畳紀に生息。

- 嚢頭綱 Thylacocephala

- 嚢頭類(ティラコセファルス類[156])。Thylacares、ドロカリス、アンキトカゾカリス[174]など。甲殻類としての位置は不確実[175]。オルドビス紀[176](カンブリア紀?)- 白亜紀に生息。

-

Brittaniclus rankini

- モリソニア目 Mollisoniida[179]

- モリソニア類。モリソニア[180]、セリオペなど。鋏角類/真鋏角類のいずれかのステムグループ[168][179]。カンブリア紀 - オルドビス紀に生息。

- (亜門[181])Artiopoda[182][145]

- 三葉虫、光楯類など。真節足動物[140]/鋏角類[164][66]/大顎類[139][110][162]のいずれかのステムグループ。カンブリア紀 - ペルム紀に生息。

- (上綱[181])Vicissicaudata - シドネイア、エメラルデラ、ケロニエロン類、光楯類など。

- 三葉形類 Trilobitomorpha

- Petalopleura - シンダレラ、シャンダレラなど。

- Nektaspida - ナラオイアなど。

- Conciliterga - クアマイア、サペリオンなど。

- 三葉虫綱 Trilobita - 三葉虫。

旧分類[編集]

分子系統学・分岐分類学が盛行する以前には、形態に基づく以下の分類体系が使用されていた。流通している書籍と文献にもこの分類にしたがっているものも多い。よって参考・比較のため、また生物学史上の意義もあり、以下に併記する。

- 大顎亜門 Mandibulata(その後の大顎類に相当)

人間との関わり[編集]

この節の加筆が望まれています。 |

食文化[編集]

節足動物は人間の食文化と深く関わっている。食材・食品の生成・農作物の繁殖などに貢献するものがあれば、食害を与えるものもある。

食材とされる節足動物の中で甲殻類は特に代表的で、カニ・エビなどの十脚類は世界中に魚介類として一般的である。それ以外の甲殻類、例えばアミ・オキアミ・フジツボなどにも食用とされる場合がある。クモ・サソリ・ムカデ・昆虫などという一般に「虫」と扱われる節足動物の中でも、地域により一般的な食材とされる種類がある(昆虫食)。蜂蜜(ミツバチによる)やミルベンケーゼ(チーズダニによる)[183]のように、特定の節足動物の生態行動による産物が食品とされるものがあり、カイガラムシのように分泌物(ラックカイガラムシなどによるシェラック)や色素(コチニールカイガラムシなどによるコチニール)が食品添加物として用いられるものもある[184][185][186]。また、節足動物は農作物の重要な授粉者であり、例えば2005年中の節足動物の授粉は1530億ユーロに値するほどの経済価値をもつと推定され、これは当時人間の食品に用いられる農業生産の9.5%を占める[187]。

一方で、人間の食材や食品を食害する節足動物もあり、特に農作物を食害するものは農業害虫に含まれる。このような害虫とされる種類を持つ節足動物は、バッタ(蝗害など)・カメムシ(ミナミアオカメムシなど)・アブラムシ・甲虫(コクゾウムシなど)・鱗翅類(農作物を食害するイモムシとケムシ)などの昆虫のみならず、ダニ(ハダニなど)・ヤスデ[188]にも食害を与える種類がある。

観賞[編集]

節足動物は観賞目的でペットとして飼育されることが多い。その範囲は幅広く、陸生の昆虫やクモガタ類から水生の甲殻類まで及ぶ。有名なものとして甲虫(カブトムシ、クワガタムシなど)・十脚類(ヤドカリ、ザリガニなど)[189]・オオツチグモ[190][191]などが挙げられる。一部の分類群に対して累代飼育方法や飼料が開発され(昆虫ゼリーなど)、また節足動物そのものが飼育キットとセットで販売されることもある(カブトエビ、アルテミアなど)[192]。

医学[編集]

医学の分野に貢献・利用されることが代表的な節足動物としてカブトガニが挙げられる。この類の血リンパには細菌の内毒素と反応して凝固する成分をもち、その毒素を検出するための試薬として用いられる[193][194]。他には一部の昆虫が地域により伝統薬として用いられ、その防御用の化学物質が現代医学で新しい薬品などの開発に繋がる可能性も示される[195]。

一方、ヒトに対して刺咬・吸血・接触・寄生・媒介などにより疾患を発生させ、衛生害虫に含まれる節足動物もある。これは吸血性で感染症を媒介するカやマダニが代表的で、例えばハマダラカが媒介するマラリアは、2000年から2020年間に全世界では約17億人が感染し、そのうち約1,060万人が死亡していると推定される[196]。

日本に生息し、疾患を発生させる危険性をもつ節足動物は、以下の例が挙げられる[197]。

- 刺咬性のもの

- 吸血性のもの

- 接触性のもの

- 鱗翅類(昆虫類) - ドクガやチャドクガなどの毒針毛とイラガなどの毒棘による皮膚炎[201]。

- 甲虫類(昆虫類) - アオバアリガタハネカクシから分泌されるペデリンによる皮膚炎[201]。アオカミキリモドキなどから分泌されるカンタリジンによる水疱性皮膚炎[201]。ミイデラゴミムシから噴射されるガスに含まれるベンゾキノンによる皮膚炎[201]。オサムシ類やマイマイカブリから噴射されるメタアクリル酸による皮膚炎[201]。

- カメムシ類(半翅類) - クサギカメムシの分泌液による皮膚炎[201]。

- サソリモドキ類(クモガタ類) - アマミサソリモドキやタイワンサソリモドキから噴射される酢酸を含む液体による皮膚炎[201]。

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c d e f g Daley, Allison; Antcliffe, Jonathan; Drage, Harriet; Pates, Stephen (2018-05-21). “Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: 201719962. doi:10.1073/pnas.1719962115.

- ^ Carlos A. Martínez-Muñoz (2023). “The correct authorship of Arthropoda—A reappraisal”. Integrative Systematics: Stuttgart Contributions to Natural History 6 (1). doi:10.18476/2023.472723.

- ^ a b Siebold, C. Th. E. von; Siebold, C. Th E. von; Stannius, Hermann (1848). Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie der Wirbellosen Thiere. Erster Theil. In Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie (eds C. T. von Siebold and H. Stannius). Berlin: Verlag von Veit & Comp.. pp. 679

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2019-06-17). “The Phylogeny and Evolutionary History of Arthropods”. Current Biology 29 (12): R592–R602. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.057. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ a b c “Arthropoda (arthropods)” (英語). Animal Diversity Web. 2018年10月24日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2013). Minelli, Alessandro; Boxshall, Geoffrey; Fusco, Giuseppe. eds (英語). The Arthropoda: A Phylogenetic Framework. In book: Arthropod Biology and Evolution – Molecules, Development, Morphology (pp.17-40)Chapter: The Arthropoda: a phylogenetic framework. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 17–40. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36160-9_2. ISBN 978-3-642-36159-3

- ^ 宮崎勝己 著「節足動物における分類学の歴史」、石川, 良輔、岩槻, 邦男、馬渡, 峻輔監修 編『節足動物の多様性と系統』裳華房〈バイオディバーシティ・シリーズ6〉、2008年4月11日、2頁。ISBN 978-4-7853-5829-7。

- ^ a b (英語) A Dictionary of Entomology. CABI. (2011). ISBN 9781845935429

- ^ Braddy, Simon J; Poschmann, Markus; Tetlie, O. Erik (2008-02-23). “Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod”. Biology Letters 4 (1): 106–109. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491. PMC 2412931. PMID 18029297.

- ^ a b Dunlop, Jason A. (2019-01-01). “Miniaturisation in Chelicerata” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 48: 20–34. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2018.10.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Davies, Neil S.; Garwood, Russell J.; McMahon, William J.; Schneider, Joerg W.; Shillito, Anthony P. (2021-12-20). “The largest arthropod in Earth history: insights from newly discovered Arthropleura remains (Serpukhovian Stainmore Formation, Northumberland, England)”. Journal of the Geological Society 179 (3): jgs2021–115. doi:10.1144/jgs2021-115. ISSN 0016-7649.

- ^ a b Ewer, John (2005-10-11). “How the Ecdysozoan Changed Its Coat” (英語). PLOS Biology 3 (10): e349. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030349. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 1250302. PMID 16207077.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fusco, Giuseppe; Minelli, Alessandro (2013). Minelli, Alessandro; Boxshall, Geoffrey; Fusco, Giuseppe. eds (英語). Arthropod Biology and Evolution: Molecules, Development, Morphology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 197–221. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36160-9_9. ISBN 978-3-642-36160-9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Javier Ortega-Hernández, Ralf Janssen, Graham E. Budd (2017-05-01). “Origin and evolution of the panarthropod head – A palaeobiological and developmental perspective” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 354–379. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.011. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Khanna, D. R. (2004) (英語). Biology of Arthropoda. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 9788171418978

- ^ a b c d 季雄, 椎野「甲殻類系統発生雑記(動物分類学会シンポジウム講演要旨)」『動物分類学会会報』第28巻、1963年、7–12頁、doi:10.19004/jsszc.28.0_7。

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; R. S. Fox; R. D. Barnes (2004), Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.), Brooks/Cole, ISBN 0-03-025982-7

- ^ a b Haas, M. Susan; Brown, Susan J.; Beeman, Richard W. (2001-03-08). “Homeotic evidence for the appendicular origin of the labrum in Tribolium castaneum” (英語). Development Genes and Evolution 211 (2): 96–102. doi:10.1007/s004270000129. ISSN 0949-944X.

- ^ a b Du, Xiaoliang; Yue, Chao; Hua, Baozhen (2009-08). “Embryonic development of the scorpionfly Panorpa emarginata Cheng with special reference to external morphology (Mecoptera: Panorpidae)” (英語). Journal of Morphology 270 (8): 984–995. doi:10.1002/jmor.10736. ISSN 0362-2525.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Javier, Ortega-Hernández, (2016). “Making sense of ‘lower’ and ‘upper’ stem-group Euarthropoda, with comments on the strict use of the name Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848” (英語). Biological Reviews 91 (1): 255-273. ISSN 1464-7931.

- ^ a b Boxshall, G. (2009年). “Exopodites , Epipodites and Gills in Crustaceans” (英語). www.semanticscholar.org. 2021年12月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f Yang, Jie; Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Legg, David A.; Lan, Tian; Hou, Jin-bo; Zhang, Xi-guang (2018-02-01). “Early Cambrian fuxianhuiids from China reveal origin of the gnathobasic protopodite in euarthropods” (英語). Nature Communications 9 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02754-z. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ a b Liu, Yu; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Schmidt, Michel; Bond, Andrew D.; Melzer, Roland R.; Zhai, Dayou; Mai, Huijuan; Zhang, Maoyin et al. (2021-07-30). “Exites in Cambrian arthropods and homology of arthropod limb branches” (英語). Nature Communications 12 (1): 4619. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24918-8. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ a b Wootton, R. (1999). “Invertebrate paraxial locomotory appendages: design, deformation and control.”. The Journal of experimental biology.

- ^ a b c d SHULTZ, JEFFREY W. (1989-09-01). “Morphology of locomotor appendages in Arachnida: evolutionary trends and phylogenetic implications”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 97 (1): 1–56. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1989.tb00552.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Alexander, David E. (2017-01-01), Alexander, David E., ed. (英語), Chapter 5 - Systems and Scaling, Academic Press, pp. 121–150, ISBN 978-0-12-804404-9 2022年4月16日閲覧。

- ^ Frantsevich, Leonid; Wang, Weiying (2009-01-01). “Gimbals in the insect leg” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 38 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2008.06.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Turetzek, Natascha; Pechmann, Matthias; Schomburg, Christoph; Schneider, Julia; Prpic, Nikola-Michael (2016-01-01). “Neofunctionalization of a Duplicate dachshund Gene Underlies the Evolution of a Novel Leg Segment in Arachnids”. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (1): 109–121. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv200. ISSN 0737-4038.

- ^ Nadein, K.; Gorb, S. (2022-01). “Lubrication in the joints of insects (Arthropoda: Insecta)” (英語). Journal of Zoology 316 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1111/jzo.12922. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ a b c Runge, Jens; Wirkner, Christian S. (2020-12). “Evolutionary and functional substitution of extrinsic musculature in Solifugae (Arachnida)” (英語). Journal of Morphology 281 (12): 1524–1533. doi:10.1002/jmor.21260. ISSN 0362-2525.

- ^ a b Bitsch, Colette; Bitsch, Jacques (2002-02). “The endoskeletal structures in arthropods: cytology, morphology and evolution” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 30 (3): 159–177. doi:10.1016/S1467-8039(01)00032-9.

- ^ “endosterniteの意味・使い方”. eow.alc.co.jp. 2022年8月5日閲覧。

- ^ Shultz, Jeffrey W. (2007-03-01). “Morphology of the prosomal endoskeleton of Scorpiones (Arachnida) and a new hypothesis for the evolution of cuticular cephalic endoskeletons in arthropods” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 36 (1): 77–102. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2006.08.001. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Brunet, Thibaut; Arendt, Detlev (2016-07-25). “Animal Evolution: The Hard Problem of Cartilage Origins” (英語). Current Biology 26 (14): R685–R688. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.062. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ Schenk, Steve C.; Wainwright, Peter C. (2001-09). “Dimorphism and the functional basis of claw strength in six brachyuran crabs” (英語). Journal of Zoology 255 (1): 105–119. doi:10.1017/S0952836901001157. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ Taylor, Graeme M. (2001). “THE EVOLUTION OF ARMAMENT STRENGTH: EVIDENCE FOR A CONSTRAINT ON THE BITING PERFORMANCE OF CLAWS OF DUROPHAGOUS DECAPODS” (英語). Evolution 55 (3): 550. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0550:TEOASE]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0014-3820.

- ^ Fujiwara, Shin-ichi; Kawai, Hiroki (2016-10). “Crabs grab strongly depending on mechanical advantages of pinching and disarticulation of chela: Functional Morphology Of Decapod Chela” (英語). Journal of Morphology 277 (10): 1259–1272. doi:10.1002/jmor.20573.

- ^ Sensenig, Andrew T.; Shultz, Jeffrey W. (2003-02-15). “Mechanics of cuticular elastic energy storage in leg joints lacking extensor muscles in arachnids”. Journal of Experimental Biology 206 (4): 771–784. doi:10.1242/jeb.00182. ISSN 0022-0949.

- ^ a b c Rainer F. Foelix (2011). Biology of spiders (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-981324-7. OCLC 693776865

- ^ a b Vannier, Jean; Liu, Jianni; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Vinther, Jakob; Daley, Allison C. (2014-05-02). “Sophisticated digestive systems in early arthropods” (英語). Nature Communications 5 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1038/ncomms4641. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ “Digestive System” (英語). ENT 425 - General Entomology. 2022年7月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (Antennal gland)”. research.nhm.org. 2022年7月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (Maxillary gland)”. research.nhm.org. 2022年7月29日閲覧。

- ^ Little, Colin; Little, Honorary Research Associate Colin (1983-12-15) (英語). The Colonisation of Land: Origins and Adaptations of Terrestrial Animals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-25218-8

- ^ WENNING, ANGELA; GREISINGER, U. T. E.; PROUX, JACQUES P. (1991-07-01). “Insect-Like Characteristics of the Malpighian Tubules of a Non-Insect: Fluid Secretion in the Centipede Uthobius Forficatus (Myriapoda: Chilopoda)”. Journal of Experimental Biology 158 (1): 165–180. doi:10.1242/jeb.158.1.165. ISSN 0022-0949.

- ^ Hazelton, S. Renee; Townsend, Victor R.; Richter, Courtney; Ritter, Marnie E.; Felgenhauer, Bruce E.; Spring, Jeffrey H. (2002-01). “Morphology and ultrastructure of the malpighian tubules of the Chilean common tarantula (Araneae: Theraphosidae)” (英語). Journal of Morphology 251 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1002/jmor.1074. ISSN 0362-2525.

- ^ O'Donnell, Michael J.; Ianowski, Juan P.; Linton, Stuart M.; Rheault, Mark R. (2003-12-30). “Inorganic and organic anion transport by insect renal epithelia” (英語). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1618 (2): 194–206. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.07.003. ISSN 0005-2736.

- ^ Wyatt, G. R. (1961-01). “The Biochemistry of Insect Hemolymph” (英語). Annual Review of Entomology 6 (1): 75–102. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.06.010161.000451. ISSN 0066-4170.

- ^ Grigorian, Melina; Hartenstein, Volker (2013-3). “Hematopoiesis and Hematopoietic Organs in Arthropods”. Development genes and evolution 223 (0): 10.1007/s00427–012–0428-2. doi:10.1007/s00427-012-0428-2. ISSN 0949-944X. PMC 3873168. PMID 23319182.

- ^ Richter; Scholtz (2001-09). “Phylogenetic analysis of the Malacostraca (Crustacea)” (英語). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 39 (3): 113–136. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0469.2001.00164.x. ISSN 0947-5745.

- ^ Smarandache-Wellmann, Carmen Ramona (10 24, 2016). “Arthropod neurons and nervous system”. Current biology: CB 26 (20): R960–R965. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.063. ISSN 1879-0445. PMID 27780069.

- ^ a b 村上安則 著「神経系の発生 ―ひとりでに出来上がるコンピュータ」、公益社団法人 日本動物学会 編『動物学の百科事典』丸善出版、2018年9月28日、310-311頁。ISBN 978-4621303092。

- ^ Scholtz, Gerhard; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2006-07-01). “The evolution of arthropod heads: reconciling morphological, developmental and palaeontological evidence” (英語). Development Genes and Evolution 216 (7): 395–415. doi:10.1007/s00427-006-0085-4. ISSN 1432-041X.

- ^ a b c d 水波誠 著「昆虫の微小脳 ―小さな脳のすごい働き」、公益社団法人 日本動物学会 編『動物学の百科事典』丸善出版、2018年9月28日、362-363頁。ISBN 978-4621303092。

- ^ Lev, Oren; Edgecombe, Gregory D; Chipman, Ariel D (2022-01-01). “Serial Homology and Segment Identity in the Arthropod Head”. Integrative Organismal Biology 4 (1): obac015. doi:10.1093/iob/obac015. ISSN 2517-4843. PMC 9128542. PMID 35620450.

- ^ Reissland, Andreas; Görner, Peter (1985), Barth, Friedrich G., ed. (英語), Trichobothria, Springer, pp. 138–161, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-70348-5_8, ISBN 978-3-642-70348-5 2022年7月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Lamsdell, James C.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2017-05). “Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 395–418. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.05.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Edwards, J. S.; Palka, J. (1974). “The Cerci and Abdominal Giant Fibres of the House Cricket, Acheta domesticus. I. Anatomy and Physiology of Normal Adults”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 185 (1078): 83–103. ISSN 0080-4649.

- ^ Sombke, Andy; Klann, Anja E.; Lipke, Elisabeth; Wolf, Harald (2019-08-02). “Primary processing neuropils associated with the malleoli of camel spiders (Arachnida, Solifugae): a re-evaluation of axonal pathways”. Zoological Letters 5 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s40851-019-0137-z. ISSN 2056-306X. PMC 6679463. PMID 31388441.

- ^ Bailey, Winston J. (1993-04-01). “The tettigoniid (Orthoptera : Tettigoniidae) ear: Multiple functions and structural diversity” (英語). International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology 22 (2): 185–205. doi:10.1016/0020-7322(93)90009-P. ISSN 0020-7322.

- ^ “Acoustic Receivers: From Insect Ear to Next-Generation Sensor | ARCHIE-WeSt”. 2018年12月20日閲覧。

- ^ Yager, David; Hoy, Ron (1988-01-01). “The midline metathoracic ear of the praying mantis, Mantis religiosa”. Cell and tissue research 250: 531-541. doi:10.1007/BF00218944.

- ^ Yack, Jayne E. (2004-04-15). “The structure and function of auditory chordotonal organs in insects” (英語). Microscopy Research and Technique 63 (6): 315–337. doi:10.1002/jemt.20051. ISSN 1059-910X.

- ^ a b c Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2015-06-15). “Homology of Head Sclerites in Burgess Shale Euarthropods” (英語). Current Biology 25 (12): 1625-1631. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.034. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ a b Miether, Sebastian T.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2016/07). “Lateral eye evolution in the arachnids”. Arachnology 17 (2): 103-119. doi:10.13156/arac.2006.17.2.103. ISSN 2050-9928.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moysiuk, Joseph; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2022-07-08). “A three-eyed radiodont with fossilized neuroanatomy informs the origin of the arthropod head and segmentation” (English). Current Biology 0 (0). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.027. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 35809569.

- ^ Kühl, Gabriele; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Rust, Jes (2009-02-06). “A Great-Appendage Arthropod with a Radial Mouth from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate, Germany” (英語). Science 323 (5915): 771-773. doi:10.1126/science.1166586. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19197061.

- ^ Paterson, John R.; García-Bellido, Diego C.; Lee, Michael S. Y.; Brock, Glenn A.; Jago, James B.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2011-12). “Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes” (英語). Nature 480 (7376): 237–240. doi:10.1038/nature10689. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Strausfeld, Nicholas J.; Ma, Xiaoya; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Fortey, Richard A.; Land, Michael F.; Liu, Yu; Cong, Peiyun; Hou, Xianguang (2016-03). “Arthropod eyes: The early Cambrian fossil record and divergent evolution of visual systems” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 45 (2): 152–172. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2015.07.005.

- ^ Snodgrass, R. E. (2019-05-20) (英語). XI. The Hexapoda. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-013/html. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ Morgan, Ann H.; O'Neil, Helen D. (1931). “The Function of the Tracheal Gills in Larvae of the Caddis Fly, Macronema zebratum Hagen”. Physiological Zoology 4 (3): 361–379. ISSN 0031-935X.

- ^ de Pennart, Auguste; Matthews, Philip G. D. (2020-01-01). “The bimodal gas exchange strategies of dragonfly nymphs across development” (英語). Journal of Insect Physiology 120: 103982. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2019.103982. ISSN 0022-1910.

- ^ a b Snodgrass, R. E. (2019-05-20) (英語). VIII. The Diplopoda. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-010/html. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ Hilken, Gero; Rosenberg, Jörg; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Blüml, Valentin; Hammel, Jörg U.; Hasenberg, Anja; Sombke, Andy (2021-01-01). “The tracheal system of scutigeromorph centipedes and the evolution of respiratory systems of myriapods” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 60: 101006. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2020.101006. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Snodgrass, R. E. (2019-05-20) (英語). X. The Symphyla. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-012/html. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ Woods, H. Arthur; Lane, Steven J.; Shishido, Caitlin; Tobalske, Bret W.; Arango, Claudia P.; Moran, Amy L. (2017-07-10). “Respiratory gut peristalsis by sea spiders” (English). Current Biology 27 (13): R638–R639. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.062. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28697358.

- ^ Unwin, Earnest Ewart (1931). “On the structure of the respiratory organs of the terrestrial Isopoda” (英語). Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania: 37–104. ISSN 0080-4703.

- ^ Hornung, Elisabeth (2011). “Evolutionary adaptation of oniscidean isopods to terrestrial life: Structure, physiology and behavior”. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4 (2): 95. ISSN 1874-9828.

- ^ Farrelly, C.A.; Greenaway, P. (2005-1). “The morphology and vasculature of the respiratory organs of terrestrial hermit crabs (Coenobita and Birgus): gills, branchiostegal lungs and abdominal lungs” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 34 (1): 63–87. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2004.11.002.

- ^ Dodson, Stanley L.; Cáceres, Carla E.; Rogers, D. Christopher (2010-01-01), Thorp, James H.; Covich, Alan P., eds. (英語), Chapter 20 - Cladocera and Other Branchiopoda, Academic Press, pp. 773–827, ISBN 978-0-12-374855-3 2022年8月1日閲覧。

- ^ Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2007-01-01). “Evolutionary Biology of Centipedes (Myriapoda: Chilopoda)”. Annual Review of Entomology 52 (1): 151–170. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091326. ISSN 0066-4170.

- ^ Fusco, Giuseppe; Minelli, Alessandro (2021). “The Development of Arthropod Segmentation Across the Embryonic/Post-embryonic Divide – An Evolutionary Perspective”. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.622482/full. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ “An Animated Guide to This Year's Massive Brood X Cicada Emergence” (英語). Time. 2022年8月5日閲覧。

- ^ Reboleira, Ana Sofia P. S.; Enghoff, Henrik (2016-05-01). “Mud and silk in the dark: A new type of millipede moulting chamber and first observations on the maturation moult in the order Callipodida” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 45 (3): 301–306. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.04.001. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b Telford, Maximilian J; Bourlat, Sarah J; Economou, Andrew; Papillon, Daniel; Rota-Stabelli, Omar (2008-04-27). “The evolution of the Ecdysozoa”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363 (1496): 1529–1537. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2243. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2614232. PMID 18192181.

- ^ a b Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2009-06). “Palaeontological and Molecular Evidence Linking Arthropods, Onychophorans, and other Ecdysozoa” (英語). Evolution: Education and Outreach 2 (2): 178–190. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0118-3. ISSN 1936-6434.

- ^ a b c Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2017-09-01). “Current Understanding of Ecdysozoa and its Internal Phylogenetic Relationships”. Integrative and Comparative Biology 57 (3): 455–466. doi:10.1093/icb/icx072. ISSN 1540-7063.

- ^ Haeckel E. 1866. Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Allgemeine Grundzüge der Organischen formen-wissenschaft, mechanisch begründet durch die von Charles Darwin reformirte descendenztheorie, 2 vols. Berlin: Georg Reimer.

- ^ Snodgrass, Robert Evans. 1938. "Evolution of the annelida onychophora and arthropoda." Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 97 (6):1–159.

- ^ Boudreaux, H. Bruce (1979). Arthropod phylogeny with special reference to insects. Internet Archive. New York : Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-04290-7

- ^ Dzik, Jerzy; Krumbiegel, Günter (1989). “The oldest ‘onychophoran’Xenusion: a link connecting phyla?” (英語). Lethaia 22 (2): 169–181. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1989.tb01679.x. ISSN 1502-3931.

- ^ MONGE-NAJERA, JULIAN (1995-05-01). “Phylogeny, biogeography and reproductive trends in the Onychophora”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 114 (1): 21–60. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1995.tb00111.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ LANKESTER, E. RAY (1904-03-01). “Memoirs: The Structure and Classification of the Arthropoda”. Journal of Cell Science s2-47 (188): 523–582. doi:10.1242/jcs.s2-47.188.523. ISSN 0021-9533.

- ^ Vandel A. 1949. Arthropodes: Généralités, composition de l’embranchement. In: Grassé pp, ed. Traité de Zoologie, 6. Paris: Masson, 79–158.

- ^ SALVADOR V. PERIS 1971. Los órdenes de los artrópodos. Trab. Cátedra Artrópodos (Fac. Biología, Univ. Complutense) 1. 1-121

- ^ Aguinaldo, Anna Marie A.; Turbeville, James M.; Linford, Lawrence S.; Rivera, Maria C.; Garey, James R.; Raff, Rudolf A.; Lake, James A. (1997-05). “Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods and other moulting animals” (英語). Nature 387 (6632): 489–493. doi:10.1038/387489a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Adoutte, A; Balavoine, Guillaume; Lartillot, N; Lespinet, O; Prud’homme, B; de Rosa, R (2000-05-01). The new animal phylogeny: Reliability and implications. 97

- ^ Seaver, Elaine C.; Kaneshige, Lori M. (2006-01-01). “Expression of ‘segmentation’ genes during larval and juvenile development in the polychaetes Capitella sp. I and H. elegans” (英語). Developmental Biology 289 (1): 179–194. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.025. ISSN 0012-1606.

- ^ Mayer, Georg (2006-03-01). “Origin and differentiation of nephridia in the Onychophora provide no support for the Articulata” (英語). Zoomorphology 125 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1007/s00435-005-0006-5. ISSN 1432-234X.

- ^ Chipman, Ariel D. (2010). “Parallel evolution of segmentation by co-option of ancestral gene regulatory networks” (英語). BioEssays 32 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1002/bies.200900130. ISSN 1521-1878.

- ^ Storch, Volker; Jamieson, Barrie G. M. (1992-02-01). “Further spermatological evidence for including the pentastomida (tongue worms) in the Crustacea” (英語). International Journal for Parasitology 22 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1016/0020-7519(92)90085-Y. ISSN 0020-7519.

- ^ Lavrov, Dennis V.; Brown, Wesley M.; Boore, Jeffrey L. (2004-03-07). “Phylogenetic position of the Pentastomida and (pan)crustacean relationships”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 271 (1538): 537–544. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2631. PMC 1691615. PMID 15129965.

- ^ Nielsen, C. (1995). Animal Evolution, Interrelationships of the Living Phyla. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ Persson, Dennis K.; Halberg, Kenneth A.; Jørgensen, Aslak; Møbjerg, Nadja; Kristensen, Reinhardt M. (2012-11-01). “Neuroanatomy of Halobiotus crispae (Eutardigrada: Hypsibiidae): Tardigrade brain structure supports the clade panarthropoda” (英語). Journal of Morphology 273 (11). doi:10.1002/jmor.20054/abstract. ISSN 1097-4687.

- ^ Hyun Ryu, Shi; Lee, Jimin; Jang, Kuem-Hee; Hwa Choi, Eun; Ju Park, Shin; Chang, Cheon; Kim, Won; Hwang, Ui Wook (2008-01-01). “Partial mitochondrial gene arrangements support a close relationship between Tardigrada and Arthropoda”. Molecules and cells 24: 351-357.

- ^ Omar Rota-Stabelli, Ehsan Kayal, Dianne Gleeson, Jennifer Daub, Jeffrey L. Boore, Maximilian J. Telford, Davide Pisani, Mark Blaxter & Dennis V. Lavrov (2010). “Ecdysozoan mitogenomics: evidence for a common origin of the legged invertebrates, the Panarthropoda”. Genome Biology and Evolution 2: 425–440. doi:10.1093/gbe/evq030. PMID 20624745.

- ^ Ahlrichs, Wilko (1995) (German). Ultrastruktur und Phylogenie von Seison nebaliae (Grube 1859) und Seison annulatus (Claus 1876) : Hypothesen zu phylogenetischen Verwandtschaftsverhältnissen innerhalb der Bilateria. Cuvillier. ISBN 978-3-89588-295-1. OCLC 40302795

- ^ HejnolAndreas 著、WanningerAndreas 編(英語)『Cycloneuralia』Springer、2015年、1–13頁。doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-1865-8_1。ISBN 978-3-7091-1865-8。2021年12月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Segmentation in Tardigrada and diversification of segmental patterns in Panarthropoda” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 328–340. (2017-05-01). doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.005. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zeng, Han; Zhao, Fangchen; Niu, Kecheng; Zhu, Maoyan; Huang, Diying (2020-12). “An early Cambrian euarthropod with radiodont-like raptorial appendages” (英語). Nature 588 (7836): 101–105. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b c Budd, Graham (1993-08). “A Cambrian gilled lobopod from Greenland” (英語). Nature 364 (6439): 709–711. doi:10.1038/364709a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ BUDD, GRAHAM E. (1996-03). “The morphology of Opabinia regalis and the reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group” (英語). Lethaia 29 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01831.x. ISSN 0024-1164.

- ^ a b Cong, Peiyun; Ma, Xiaoya; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. (2014-07-16). “Brain structure resolves the segmental affinity of anomalocaridid appendages” (英語). Nature 513 (7519): 538–542. doi:10.1038/nature13486. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b Van Roy, Peter; Daley, Allison C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2015-03-11). “Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps” (英語). Nature 522 (7554): 77–80. doi:10.1038/nature14256. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2020-11-02). “Arthropod Origins: Integrating Paleontological and Molecular Evidence”. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-124437. ISSN 1543-592X.

- ^ Collins, Desmond (1996/03). “The “evolution” of Anomalocaris and its classification in the arthropod class Dinocarida (nov.) and order Radiodonta (nov.)” (英語). Journal of Paleontology 70 (2): 280–293. doi:10.1017/S0022336000023362. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2015). “Cephalic and limb anatomy of a new Isoxyid from the Burgess Shale and the role of "stem bivalved arthropods" in the disparity of the frontalmost appendage”. PloS One 10 (6): e0124979. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124979. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4454494. PMID 26038846.

- ^ a b Pates, Stephen; Wolfe, Joanna; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Daley, Allison; Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2022-02-09). “New opabiniid diversifies the weirdest wonders of the euarthropod stem group”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 289: 20212093. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.2093.

- ^ Rempel, J. G. (1975). “The Evolution of the Insect Head: the Endless Dispute”. Quaestiones entomologicae 11 (1): 7–24. ISSN 0033-5037.

- ^ a b Størmer, Leif (1944) (English). On the relationships and phylogeny of fossil and recent Arachnomorpha: a comparative study on Arachnida, Xiphosura, Eurypterida, Trilobita, and other fossil Arthropoda. Oslo: Jacob Dybwad. OCLC 961296639

- ^ Kraus, O. (1998). Fortey, R. A.; Thomas, R. H.. eds (英語). Arthropod Relationships. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 295–303. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4904-4_22. ISBN 978-94-011-4904-4

- ^ Telford, Maximilian J.; Thomas, Richard H. (1998-09-01). “Expression of homeobox genes shows chelicerate arthropods retain their deutocerebral segment” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95 (18): 10671–10675. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 9724762.

- ^ Mittmann, Beate; Scholtz, Gerhard (2003-02-01). “Development of the nervous system in the "head" of Limulus polyphemus (Chelicerata: Xiphosura): morphological evidence for a correspondence between the segments of the chelicerae and of the (first) antennae of Mandibulata” (英語). Development Genes and Evolution 213 (1): 9?17. doi:10.1007/s00427-002-0285-5. ISSN 1432-041X.

- ^ “Immunohistochemical localization of neurotransmitters in the nervous system of larval Limulus polyphemus (Chelicerata, Xiphosura): evidence for a conserved protocerebral architecture in Euarthropoda” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 34 (3): 327–342. (2005-07-01). doi:10.1016/j.asd.2005.01.006. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Sharma, Prashant P.; Tarazona, Oscar A.; Lopez, Davys H.; Schwager, Evelyn E.; Cohn, Martin J.; Wheeler, Ward C.; Extavour, Cassandra G. (2015-06-07). “A conserved genetic mechanism specifies deutocerebral appendage identity in insects and arachnids”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282 (1808): 20150698. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0698. PMC 4455815. PMID 25948691.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo; Ribera, Carles (2000-06). “A Review of Arthropod Phylogeny: New Data Based on Ribosomal DNA Sequences and Direct Character Optimization” (英語). Cladistics 16 (2): 204–231. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00353.x. ISSN 0748-3007.

- ^ Nardi, Francesco; Spinsanti, Giacomo; Boore, Jeffrey L.; Carapelli, Antonio; Dallai, Romano; Frati, Francesco (2003-03-21). “Hexapod Origins: Monophyletic or Paraphyletic?” (英語). Science 299 (5614): 1887–1889. doi:10.1126/science.1078607. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12649480.

- ^ Regier, Jerome C.; Shultz, Jeffrey W.; Kambic, Robert E. (2005-02-22). “Pancrustacean phylogeny: hexapods are terrestrial crustaceans and maxillopods are not monophyletic”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272 (1561): 395–401. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2917. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1634985. PMID 15734694.

- ^ a b Regier, Jerome C.; Shultz, Jeffrey W.; Zwick, Andreas; Hussey, April; Ball, Bernard; Wetzer, Regina; Martin, Joel W.; Cunningham, Clifford W. (2010-02). “Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences” (英語). Nature 463 (7284): 1079–1083. doi:10.1038/nature08742. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Oakley, Todd H.; Wolfe, Joanna M.; Lindgren, Annie R.; Zaharoff, Alexander K. (2012-09-12). “Phylotranscriptomics to Bring the Understudied into the Fold: Monophyletic Ostracoda, Fossil Placement, and Pancrustacean Phylogeny” (英語). Molecular Biology and Evolution 30 (1): 215–233. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss216. ISSN 1537-1719.

- ^ Harrison, Jon Fewell (2015年). “Linking Insects with Crustacea : Comparative Physiology of the Pancrustacea Organized by” (英語). 2018年10月24日閲覧。

- ^ Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus; Giacomelli, Mattia; Fleming, James F; Chen, Albert; Vinther, Jakob; Thomsen, Philip Francis; Glenner, Henrik; Palero, Ferran et al. (2019-08-01). “Pancrustacean Evolution Illuminated by Taxon-Rich Genomic-Scale Data Sets with an Expanded Remipede Sampling”. Genome Biology and Evolution 11 (8): 2055–2070. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz097. ISSN 1759-6653.

- ^ Dunlop, Jason; Borner, Janus; Burmester, Thorsten (2014-02-27) (英語). 16 Phylogeny of the Chelicerates: Morphological and molecular evidence. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110277524.399. ISBN 978-3-11-027752-4

- ^ Hassanin, Alexandre; Prieur, Stéphanie le; Bonillo, Céline; Krapp, Franz; Corbari, Laure; Sabroux, Romain (2017-02-24). “Biodiversity and phylogeny of Ammotheidae (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida)” (英語). European Journal of Taxonomy 0 (286). doi:10.5852/ejt.2017.286. ISSN 2118-9773.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Wheeler, Ward C. (2001-09). “Arthropod phylogeny based on eight molecular loci and morphology” (英語). Nature 413 (6852): 157–161. doi:10.1038/35093097. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Dunlop, J. A.; Arango, C. P. (2005). “Pycnogonid affinities: A review”. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 43: 8–21. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2004.00284.x.

- ^ Lamsdell, James (2013-01-01). “Revised systematics of Palaeozoic ‘horseshoe crabs’ and the myth of monophyletic Xiphosura”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 167: 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00874.x.

- ^ Scholtz, Gerhard; Edgecombe, Gregory (2005-04-27), Koenemann, Stefan; Jenner, Ronald, eds. (英語), Heads, Hox and the phylogenetic position of trilobites, 16, CRC Press, pp. 139–165, doi:10.1201/9781420037548.ch6, ISBN 978-0-8493-3498-6 2022年8月1日閲覧。

- ^ a b Scholtz, Gerhard; Staude, Andreas; Dunlop, Jason A. (2019-06-07). “Trilobite compound eyes with crystalline cones and rhabdoms show mandibulate affinities” (英語). Nature Communications 10 (1): 1-7. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-10459-8. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2017-05). “Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan” (英語). Nature 545 (7652): 89–92. doi:10.1038/nature22080. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b Tanaka, Gengo; Hou, Xianguang; Ma, Xiaoya; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. (2013-10). “Chelicerate neural ground pattern in a Cambrian great appendage arthropod” (英語). Nature 502 (7471): 364–367. doi:10.1038/nature12520. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b c d Vannier, Jean; Aria, Cédric; Taylor, Rod S.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2018). “Waptia fieldensis Walcott, a mandibulate arthropod from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale”. Royal Society Open Science 5 (6): 172206. doi:10.1098/rsos.172206. PMC 6030330. PMID 30110460.

- ^ Legg, David (2013-06). The impact of fossils on arthropod phylogeny.

- ^ 宮崎勝己「節足動物全体の分類体系・系統の現状」石川良輔編『節足動物の多様性と系統』〈バイオディバーシティ・シリーズ〉第6巻、岩槻邦男・馬渡峻輔監修、裳華房、2008年、11-27頁。

- ^ a b c d Hou, Xianguang; Bergström, Jan (1997). Arthropods of the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna, southwest China. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. ISBN 82-00-37693-1. OCLC 38305908

- ^ a b 鈴木雄太郎「三葉虫綱」石川良輔編『節足動物の多様性と系統』〈バイオディバーシティ・シリーズ〉第6巻、岩槻邦男・馬渡峻輔監修、裳華房、2008年、114-121頁。

- ^ Basset, Yves; Cizek, Lukas; Cuenoud, Philippe; Didham, Raphael; Guilhaumon, Francois; Missa, Olivier; Novotny, Vojtech; Ødegaard, Frode et al. (2012-12-14). “Arthropod Diversity in a Tropical Forest”. Science 338: 1481–1484. doi:10.1126/science.1226727.

- ^ Zhi-Qiang Zhang (2011), “Phylum Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848”. In: Zhang Z.-Q. (Ed.), Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa, Volume 3148, Magnolia Press, Pages 99-103.

- ^ “What are trilobites? - Australian Museum” (英語). australianmuseum.net.au. 2018年10月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b Sharma, Prashant P.; Ballesteros, Jesús A.; Santibáñez-López, Carlos E. (2021-11). “What Is an “Arachnid”? Consensus, Consilience, and Confirmation Bias in the Phylogenetics of Chelicerata” (英語). Diversity 13 (11): 568. doi:10.3390/d13110568. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ a b 金子, 隆一 (2012) (Japanese). ぞわぞわした生きものたち: 古生代の巨大節足動物. 東京: ソフトバンククリエイティブ. ISBN 978-4-7973-4411-0. OCLC 816905375

- ^ Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus; Tanner, Alastair R.; Giacomelli, Mattia; Carton, Robert; Vinther, Jakob; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Pisani, Davide (2019-05-24). “Increasing species sampling in chelicerate genomic-scale datasets provides support for monophyly of Acari and Arachnida” (英語). Nature Communications 10 (1): 2295. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-10244-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6534568. PMID 31127117.

- ^ a b c d e f 大塚攻、田中隼人「顎脚類(甲殻類)の分類と系統に関する研究の最近の動向」『タクサ:日本動物分類学会誌』第48巻、日本動物分類学会、2020年、49–62頁、doi:10.19004/taxa.48.0_49。

- ^ a b “岡山県野生生物目録2019 - 岡山県ホームページ(自然環境課)”. www.pref.okayama.jp. 2019年8月16日閲覧。

- ^ Chan, Benny K K; Dreyer, Niklas; Gale, Andy S; Glenner, Henrik; Ewers-Saucedo, Christine; Pérez-Losada, Marcos; Kolbasov, Gregory A; Crandall, Keith A et al. (2021-02-25). “The evolutionary diversity of barnacles, with an updated classification of fossil and living forms”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 193 (3): 789–846. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa160. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b c d e 加藤太一 (2017) (Japanese). 古生物. 東京: 学研プラス. ISBN 978-4-05-204576-9. OCLC 992701133

- ^ 土屋, 健; かわさき, しゅんいち; 田中, 源吾 (2020) (Japanese). アノマロカリス解体新書. ISBN 978-4-89308-928-1. OCLC 1141813539

- ^ a b 群馬県立自然史博物館 (2020) (Japanese). 大むかしの生きもの. 東京: 講談社. ISBN 978-4-06-518985-6. OCLC 1163637303

- ^ a b 土屋, 健; 土屋, 香; 芝原, 暁彦 (2021) (Japanese). ゼロから楽しむ古生物: 姿かたちの移り変わり. ISBN 978-4-297-12228-7. OCLC 1262176890

- ^ 小林快次 (2014) (Japanese). 大昔の生きもの. 東京: ポプラ社. ISBN 978-4-591-14071-0. OCLC 883613863

- ^ 土屋健; 群馬県立自然史博物館 (2017). 生命史図譜 = History of life. ISBN 978-4-7741-9075-4. OCLC 995843160

- ^ a b c d O’Flynn, Robert J.; Williams, Mark; Yu, Mengxiao; Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Liu, Yu. “A new euarthropod with large frontal appendages from the early Cambrian Chengjiang biota” (English). Palaeontologia Electronica 25 (1): 1–21. doi:10.26879/1167. ISSN 1094-8074.

- ^ a b Legg, David A.; Sutton, Mark D.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2012-12-07). “Cambrian bivalved arthropod reveals origin of arthrodization”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279 (1748): 4699–4704. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1958. PMC 3497099. PMID 23055069.

- ^ a b c d e f Legg, David A.; Sutton, Mark D.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2013). “Arthropod fossil data increase congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies” (英語). Nature Communications 4 (1). ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ a b Ou, Qiang; Vannier, Jean; Yang, Xianfeng; Chen, Ailin; Mai, Huijuan; Shu, Degan; Han, Jian; Fu, Dongjing et al. (2020-05). “Evolutionary trade-off in reproduction of Cambrian arthropods” (英語). Science Advances 6 (18): eaaz3376. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz3376. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7190318. PMID 32426476.

- ^ Aria, Cédric; Zhao, Fangchen; Zhu, Maoyan (2021-03-22). “Fuxianhuiids are mandibulates and share affinities with total-group Myriapoda”. Journal of the Geological Society 178 (5). doi:10.1144/jgs2020-246. ISSN 0016-7649.

- ^ Izquierdo‐López, Alejandro; Caron, Jean‐Bernard (2021-11). Zhang, Xi‐Guang. ed. “A Burgess Shale mandibulate arthropod with a pygidium: a case of convergent evolution” (英語). Papers in Palaeontology 7 (4): 1877–1894. doi:10.1002/spp2.1366. ISSN 2056-2799.

- ^ a b c Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2019-09). “A middle Cambrian arthropod with chelicerae and proto-book gills” (英語). Nature 573 (7775): 586–589. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1525-4. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b Aria, Cédric; Zhao, Fangchen; Zeng, Han; Guo, Jin; Zhu, Maoyan (2020-01-08). “Fossils from South China redefine the ancestral euarthropod body plan”. BMC Evolutionary Biology 20 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s12862-019-1560-7. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 6950928. PMID 31914921.

- ^ a b c Zhai, Dayou; Williams, Mark; Siveter, David J.; Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Sansom, Robert S.; Gabbott, Sarah E.; Siveter, Derek J.; Ma, Xiaoya et al. (2019-09-03). “Variation in appendages in early Cambrian bradoriids reveals a wide range of body plans in stem-euarthropods” (英語). Communications Biology 2 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0573-5. ISSN 2399-3642.

- ^ Hou, Xianguang; Williams, Mark; Siveter, David J.; Siveter, Derek J.; Aldridge, Richard J.; Sansom, Robert S. (2010-06-22). “Soft-part anatomy of the Early Cambrian bivalved arthropods Kunyangella and Kunmingella: significance for the phylogenetic relationships of Bradoriida”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277 (1689): 1835-1841. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2194. PMC 2871875. PMID 20181565.

- ^ Fossils and Strata, Morphology, Ontogeny and Phylogeny of the Phosphatocopina (Crustacea) from the Upper Cambrian Orsten of Sweden.. Waloszek, Dieter., Maas, Andreas., Muller, Klaus.. Wiley. (2009). ISBN 1-282-11829-3. OCLC 741343594

- ^ Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strullu-Derrien, Christine; Góral, Tomasz; Hetherington, Alexander J.; Thompson, Christine; Koch, Markus (2020-04-01). “Aquatic stem group myriapods close a gap between molecular divergence dates and the terrestrial fossil record” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1073/pnas.1920733117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 32253305.

- ^ Laville, Thomas; Smith, Christopher P. A.; Forel, Marie-Béatrice; Brayard, Arnaud; Charbonnier, Sylvain (2021-02-25). “REVIEW OF EARLY TRIASSIC THYLACOCEPHALA” (英語). RIVISTA ITALIANA DI PALEONTOLOGIA E STRATIGRAFIA 127 (1). doi:10.13130/2039-4942/15188. ISSN 2039-4942.

- ^ Lange, Sven; Schram, Frederick R.; Steeman, Fedor A.; Hof, Cees H. J. (2001). “New Genus and Species from the Cretaceous of Lebanon Links the Thylacocephala To the Crustacea” (英語). Palaeontology 44 (5): 905–912. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00207. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ Roy, Peter Van; Rak, Štěpán; Budil, Petr; Fatka, Oldřich (2021). “Upper Ordovician Thylacocephala (Euarthropoda, Eucrustacea) from Bohemia indicate early ecological differentiation” (英語). Papers in Palaeontology 7 (3): 1727–1751. doi:10.1002/spp2.1363. ISSN 2056-2802.

- ^ Schädel, Mario; Haug, Joachim T. (2020/05). “A new interpretation of the enigmatic fossil arthropod Anhelkocephalon handlirschi Bill, 1914 – important insights in the morphology of Cyclida”. Palaeodiversity 13 (1): 69–81. doi:10.18476/pale.v13.a7. ISSN 1867-6294.

- ^ a b Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2017-12). “Mandibulate convergence in an armoured Cambrian stem chelicerate” (英語). BMC Evolutionary Biology 17 (1): 261. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-1088-7. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5738823. PMID 29262772.

- ^ a b Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Skabelund, Jacob; Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2020-04-09). “Revision of the mollisoniid chelicerate(?) Thelxiope , with a new species from the middle Cambrian Wheeler Formation of Utah” (英語). PeerJ 8: e8879. doi:10.7717/peerj.8879. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ a b Gould, Stephen Jay; 渡辺, 政隆 (2000) (Japanese). ワンダフル・ライフ: バージェス頁岩と生物進化の物語. ISBN 978-4-15-050236-2. OCLC 676428996

- ^ a b Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Zhu, Xuejian; Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2017-12). “The Vicissicaudata revisited – insights from a new aglaspidid arthropod with caudal appendages from the Furongian of China” (英語). Scientific Reports 7 (1): 11117. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11610-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5593897. PMID 28894246.

- ^ Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Azizi, Abdelfattah; Hearing, Thomas W.; Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Hafid, Ahmid; El Hariri, Khadija (2017-02-17). “A xandarellid artiopodan from Morocco – a middle Cambrian link between soft-bodied euarthropod communities in North Africa and South China” (英語). Scientific Reports 7 (1). doi:10.1038/srep42616. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ “Manufaktur” (ドイツ語). Würchwitzer Milbenkäse: Der lebendigste Käse der Welt.. 2019年8月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation of cochineal, carminic acid, carmines (E 120) as a food additive | EFSA” (英語). www.efsa.europa.eu. 2022年8月12日閲覧。

- ^ “GSFA Online Food Additive Details for Shellac”. www.fao.org. 2022年8月12日閲覧。

- ^ Thombare, Nandkishore; Kumar, Saurav; Kumari, Usha; Sakare, Priyanka; Yogi, Raj Kumar; Prasad, Niranjan; Sharma, Kewal Krishan (2022-08-31). “Shellac as a multifunctional biopolymer: A review on properties, applications and future potential” (英語). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 215: 203–223. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.06.090. ISSN 0141-8130.

- ^ Gallai, Nicola; Salles, Jean-Michel; Settele, Josef; Vaissière, Bernard E. (2009-01-15). “Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline” (英語). Ecological Economics 68 (3): 810–821. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014. ISSN 0921-8009.

- ^ Ebregt, E.; Struik, P. C.; Odongo, B.; Abidin, P. E. (2005-01-01). “Pest damage in sweet potato, groundnut and maize in north-eastern Uganda with special reference to damage by millipedes (Diplopoda)”. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 53 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1016/S1573-5214(05)80010-7. ISSN 1573-5214.

- ^ 潤, 佐々木「観賞用として扱われている甲殻類の現状: 企画趣旨とシンポジウムの内容(シンポジウム報告 観賞用として扱われている甲殻類の現状)」『Cancer』第23巻、2014年、63–88頁、doi:10.18988/cancer.23.0_63。

- ^ “Query on global tarantula trade” (英語). 2022年8月12日閲覧。

- ^ Marshall, Benjamin M.; Strine, Colin T.; Fukushima, Caroline S.; Cardoso, Pedro; Orr, Michael C.; Hughes, Alice C. (2022-05-19). “Searching the web builds fuller picture of arachnid trade” (英語). Communications Biology 5 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03374-0. ISSN 2399-3642.

- ^ “History of Sea-Monkeys – The Original Sea-Monkeys”. www.sea-monkeys.com. 2022年8月8日閲覧。

- ^ Iwanaga, Sadaaki (2007). “Biochemical principle of Limulus test for detecting bacterial endotoxins”. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 83 (4): 110–119. doi:10.2183/pjab.83.110. PMC 3756735. PMID 24019589.

- ^ Sheng, Jianling; Zhou, Jufen; Peng, Yanhua; Zhu, Zhenmei; Chen, Linchu (2006-01-01). “Tachypleus Amebocyte Lysate Test Using in Transfusion Reaction” (Chinese). Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology 0 (08). ISSN 1005-4529.

- ^ Dossey, Aaron T. (2010-11-17). “Insects and their chemical weaponry: New potential for drug discovery” (英語). Natural Product Reports 27 (12): 1737–1757. doi:10.1039/C005319H. ISSN 1460-4752.

- ^ “World malaria report 2021” (英語). www.who.int. 2022年8月12日閲覧。

- ^ 夏秋優『Dr.夏秋の臨床図鑑 虫と皮膚炎』学研プラス、2013年、10頁。

- ^ a b c d e 夏秋優『Dr.夏秋の臨床図鑑 虫と皮膚炎』学研プラス、2013年、13頁。

- ^ a b c d 夏秋優『Dr.夏秋の臨床図鑑 虫と皮膚炎』学研プラス、2013年、14頁。

- ^ “CDC - DPDx - American Trypanosomiasis” (英語). www.cdc.gov (2017年12月19日). 2019年1月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g 夏秋優『Dr.夏秋の臨床図鑑 虫と皮膚炎』学研プラス、2013年、15頁。

参考文献[編集]

- 石川良輔編、岩槻邦男・馬渡峻輔監修 『節足動物の多様性と系統』 裳華房、2008年、495頁、ISBN 978-4-7853-5829-7

- 白山義久編 『無脊椎動物の多様性と系統(節足動物を除く)』 裳華房、2002年、ISBN 4-7853-5828-9

![クモ(左)とヒヨケムシ(右)の前体断面。脚の筋肉に繋がる内骨格(内腹板と腱)を示す[30]。](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Jmor21260-fig-0005-m.jpg/529px-Jmor21260-fig-0005-m.jpg)

![2017年時点で広く認められる、様々な節足動物における前部の体節と付属肢の対応関係[14][57]。先頭の合体節(頭部および前体)に含まれる体節は暗灰色で、前大脳性・中大脳性・後大脳性の体節と付属肢はそれぞれP(赤)・D(黄)T(青)で示される。](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/20220000_Arthropoda_head_segments_appendages_tagmosis_ja.png/1144px-20220000_Arthropoda_head_segments_appendages_tagmosis_ja.png)

![2017年時点で広く認められる、様々な汎節足動物における前部の体節と付属肢の対応関係[14]。先節は「0」、頭部に含まれる部分は暗灰色、前大脳性・中大脳性・後大脳性の体節と付属肢はそれぞれP(赤)・D(黄)T(青)で示される。](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/20191106_Panarthropoda_head_segments_appendages_ja.png/1472px-20191106_Panarthropoda_head_segments_appendages_ja.png)