「全身麻酔の歴史」の版間の差分

Anesth Earth (会話 | 投稿記録) →麻酔: seealso |

Anesth Earth (会話 | 投稿記録) →20世紀: 出典追加 |

||

| 174行目: | 174行目: | ||

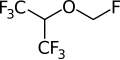

ファイル:(RS)-Desfluran Structural Formula V1.svg|[[デスフルラン]] |

ファイル:(RS)-Desfluran Structural Formula V1.svg|[[デスフルラン]] |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

100年以上の間、[[吸入麻酔薬]]の主流は1930年代に導入された[[シクロプロパン]]とエーテルのままであった。これらはいずれも引火しやすかった。1956年には、引火性がないという大きな利点を持つ[[ハロタン]]が導入された<ref name="Raventos1956">{{Cite journal|last1=Raventos|first1=J|last2=Goodall|first2=R|date=1956|title=The Action of Fluothane-A New Volatile Anaesthetic|journal=British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy|volume=11|issue=4|pages=394–410|doi=10.1111/j.1476-5381.1956.tb00007.x|pmc=1510559|pmid=13383118}}</ref>。これにより、手術室[[火災]]のリスクが減少した。1960年代には、まれにではあるが、ハロタンに不整脈や肝毒性といった重大な副作用が出たため、{{仮リンク|ハロゲン化エーテル|en|halogenated ether|redirect=1}}がハロタンに取って代わった。最初の2種類のハロゲン化エーテルは[[メトキシフルラン]]と[[エンフルラン]]であった。これらは更に1980年代から1990年代にかけて、現在の標準である[[イソフルラン]]、[[セボフルラン]]、[[デスフルラン]]に取って代わられたが、オーストラリアではメトキシフルランがペンスロックス |

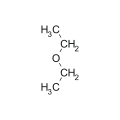

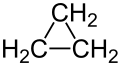

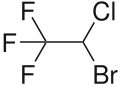

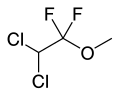

100年以上の間、[[吸入麻酔薬]]の主流は1930年代に導入された[[シクロプロパン]]とエーテルのままであった。これらはいずれも引火しやすかった。1956年には、引火性がないという大きな利点を持つ[[ハロタン]]が導入された<ref name="Raventos1956">{{Cite journal|last1=Raventos|first1=J|last2=Goodall|first2=R|date=1956|title=The Action of Fluothane-A New Volatile Anaesthetic|journal=British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy|volume=11|issue=4|pages=394–410|doi=10.1111/j.1476-5381.1956.tb00007.x|pmc=1510559|pmid=13383118}}</ref>。これにより、手術室[[火災]]のリスクが減少した。1960年代には、まれにではあるが、ハロタンに不整脈や肝毒性といった重大な副作用が出たため、{{仮リンク|ハロゲン化エーテル|en|halogenated ether|redirect=1}}がハロタンに取って代わった。最初の2種類のハロゲン化エーテルは[[メトキシフルラン]]と[[エンフルラン]]であった。これらは更に1980年代から1990年代にかけて、現在の標準である[[イソフルラン]]、[[セボフルラン]]、[[デスフルラン]]に取って代わられたが、オーストラリアではメトキシフルランがペンスロックス(商品名、Penthrox)として[[病院前救護]]の麻酔に用いられている<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Trimmel|first=Helmut|last2=Egger|first2=Alexander|last3=Doppler|first3=Reinhard|last4=Pimiskern|first4=Mathias|last5=Voelckel|first5=Wolfgang G.|date=2022-01-15|title=Usability and effectiveness of inhaled methoxyflurane for prehospital analgesia - a prospective, observational study|url=https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-021-00565-6|journal=BMC Emergency Medicine|volume=22|issue=1|pages=8|doi=10.1186/s12873-021-00565-6|issn=1471-227X|pmc=PMC8760876|pmid=35033003}}</ref>。 ハロタンは、発展途上国の多くで依然用いられている<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mahboobi|first=N.|last2=Esmaeili|first2=S.|last3=Safari|first3=S.|last4=Habibollahi|first4=P.|last5=Dabbagh|first5=A.|last6=Alavian|first6=S. M.|date=2012-02|title=Halothane: how should it be used in a developing country?|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22571093/|journal=Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue De Sante De La Mediterranee Orientale = Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit|volume=18|issue=2|pages=159–164|doi=10.26719/2012.18.2.159|issn=1020-3397|pmid=22571093}}</ref>。<gallery> |

||

ファイル:Beerse Statue Paul Janssen 070225 (cropped).JPG|ベルギーにある[[ポール・ヤンセン]]の像 |

ファイル:Beerse Statue Paul Janssen 070225 (cropped).JPG|ベルギーにある[[ポール・ヤンセン]]の像 |

||

ファイル:Haloperidol.svg|ハロペリドール |

ファイル:Haloperidol.svg|ハロペリドール |

||

2024年1月9日 (火) 14:58時点における版

全身麻酔の歴史(ぜんしんますいのれきし)では、世界の歴史において全身麻酔に関わる事物がどのような発展を遂げてきたかについて概説する。

歴史時代を通じて、全身麻酔状態を作り出す試みは、古代のシュメール人、バビロニア人、アッシリア人、エジプト人、インド人、中国人の著作にまで遡ることができる。ルネサンス期には解剖学や手術手技が大きく進歩したにもかかわらず、手術は、それに伴う痛みのため、最後の手段の治療法のままであった。しかし、18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけての科学的発見により、近代的な麻酔技術の開発への道が開かれた。

19世紀後半には、2つの大きな進歩が近代的な外科手術への移行を可能にした。すなわち、病気の病原体説の結果として無菌操作が開発・応用され、合併症と死亡率が低下したことと、薬理学と生理学の進歩によって全身麻酔と疼痛管理が開発されたことである。20世紀に入ると、全身麻酔の安全性と有効性は、気管挿管と高度な気道確保をルーチンに行い、モニタリングを行い、特性が改善された新しい麻酔薬の登場により、さらに向上した。

麻酔の語源

麻酔

日本語の「麻酔」は、英語の "anesthesia" やドイツ語の "Anästhesie" に対する訳語である。初出は杉田成卿『済生備考』(1850年)とされる[1]。これは、全身麻酔の先駆者である、華岡青洲の没後であり、青洲は自らの著述で「麻酔」という言葉を使っていない[1]。中国語でも同様に「麻醉」と記載される[2]が、日本での初出より前には用例が確認されておらず、「麻酔」が中国で日本より先に造語された可能性は低いとされる[1]。

anesthesia

『ヒポクラテス全集』『ティマイオス』などの古代ギリシア語文献には、ἀναισθησίᾱ(anaisthēsíā、無感覚)という用語があり、ἀν- (an-、「無し」)と αἴσθησις (aisthēsis、「感覚」)に由来する[3][4]。

1679年、オランダの医師ステファン・ブランカールトがラテン語の"anaisthesia"を用いたギリシャ・ラテン語医学辞典(Lexicon medicum graeco-latinum)を出版した。1684年、「身体の辞書(A Physical Dictionary)」という題名で英訳が出版され、anaisthesiaは「麻痺患者や泥酔者のような感覚の欠如」と定義された。その後、この言葉やanæsthesiaのような綴りの変化は、医学文献で「無感覚」を意味するようになった[3]。

1846年、アメリカの作家・医学者のオリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・シニアは書簡の中で、ある薬剤によって誘発される状態をanesthesia、薬剤そのものをanestheticという用語として提案した。ホームズは、医学文献におけるanesthesiaの以前の用法が、特に「触れるもの」に対する「無感覚」を意味するものであったことから、このように考えたのである[3][5][6]。

古代

全身麻酔の最初の試みは、おそらく先史時代に投与された薬草療法であろう。アルコールは最も古くから知られている鎮静剤で、数千年前の古代メソポタミアで用いられていた[7]。

アヘン

アヘンの有効成分はモルヒネであり、現在でもオピオイド鎮痛薬として用いられている[8]。シュメール人は、紀元前3400年頃にはメソポタミア下流でケシを栽培し、アヘンを収穫していたと言われているが[9][10]、これには異論がある[11]。現在までに発見されているケシに関する最も古い証言は、紀元前3千年紀の終わりに小さな白い粘土板に楔形文字で刻まれたものである。この石版は1954年、ニップルでの発掘調査で発見され、現在ペンシルベニア大学考古学人類学博物館に保管されている。サミュエル・ノア・クレイマーとマーティン・リーヴによって解読され、現存する最古の薬局方とされている[12][13]。この時代のシュメール語の石版には"hul gil"という表意文字が刻まれており、「喜びの植物」と訳されて、アヘンを意味するという説がある[14][15]。gilという言葉は、世界のある地域では今でもアヘンに用いられている[16]。シュメールの女神ニダバは、しばしば肩からケシが生えている姿で描かれている。紀元前2225年頃、シュメール領域はバビロニア帝国の一部となった。アヘンとその多幸感に関する知識と用い方はバビロニア人に伝わり、バビロニア人は帝国を東のペルシャ、西のエジプトへと拡大した。これにより、アヘンに関する知見はこれらの文明にまで広がっている[16]。イギリスの考古学者で楔形文字学者のレジナルド・キャンベル・トンプソンは、アヘンは紀元前7世紀にはアッシリア人に知られていたと書いている[17]。紀元前650年頃のアッシリアの石版に刻まれた「アッシリアの草本誌(Herbal)」の中に、"Arat Pa Pa"という言葉が出てくる。トンプソンによれば、この用語はケシの汁のアッシリア語名であり、ラテン語のケシ属(papaver)の語源である可能性があるという[14]。

古代エジプト人は、おそらくマンドレイクの果実から抽出したエキスを含む、原始的な鎮痛剤と鎮静剤だけでなく[18]、外科器具[19][20]もいくつか持っていた。アヘンに似た製剤を手術に用いたことは、第18王朝時代に書かれたエジプトの医学パピルス、エーベルス・パピルスに記録されている[16][21][19]。しかし、古代エジプトでアヘンそのものが知られていたかどうかは疑問である[22]。

ギリシャ神話の神ヒュプノス(眠り)、ニュクス(夜)、タナトス(死)は、しばしばケシを手にした姿で描かれていた[23]。

古代インドと中国にアヘンが伝来する以前、これらの文明は大麻の香とトリカブトを他に先駆けて用いていた。紀元前400年頃、インド亜大陸のアーユルヴェーダ医学と外科手術に関する書物『スシュルタ・サンヒター』では、麻酔のためにワインと大麻の香を用いることが提唱されている[24]。紀元8世紀までには、アラブの商人がインド[25]と中国[26]にアヘンを持ち込んだ。アヘンからモルヒネが単離されるにはここから2500年を待つことになる[27]。

古代中国

扁鵲(紀元前300年頃)は中国の伝説的な内科医であり外科医で、外科手技に全身麻酔を用いたと伝えられている。『韓非子』(紀元前250年頃)『史記』(紀元前100年頃)『列子』(紀元300年頃)には、扁鵲が 魯公扈と趙齊嬰という二人の男に毒物を飲ませ、三日間意識を失わせ、その間に胃瘻を造ったことが記されている[28][29][30]。

華佗は紀元2世紀の中国の外科医。『三国志』(紀元270年頃)と『後漢書』(紀元430年頃)によると、華佗は酒と麻沸散と呼ばれる薬草抽出物の混合物を用いて開発した処方で全身麻酔下の手術を行ったという[31]。華陀は、壊死した腸の部分切除のような大きな手術にも麻沸散を用いたと伝えられている[31][32][33]。手術の前に、彼はおそらく酒に溶かした麻酔薬を経口投与し、意識消失と不完全ながらな筋弛緩状態を引き起こした[31]。

麻沸散の正確な組成は、華陀の臨床知識のすべてと同様、死の直前に原稿を焼却した際に失われてしまった[34]。『三国志』にも『後漢書』にも麻酔薬の組成は記されていない。儒教の教えでは身体は神聖なものとされ、手術は身体を切り刻む行為と考えられていたため、古代中国では手術は強く禁じられていた[31]。そのため、華陀が全身麻酔に成功したと伝えられているにもかかわらず、古代中国における外科手術は彼の死とともに終焉を迎えた[31]。

麻沸散という名前は、麻(「大麻、麻、しびれる、うずく」の意)、沸(「沸騰する、泡立つ」の意)、散(「砕く、散らばる」の意、「粉末状の薬」の意)を組み合わせたものである。従って、麻沸散という言葉からは大麻を含むものと推測されてきたが、これに関しては当時の中国大陸には中枢神経作用のある大麻が伝来していなかったことから異論もある[35]。多くの中国学者や中国医学の研究者が、華陀の麻沸散の成分を推測しているが、正確な成分はいまだに不明である。彼の処方には、以下の組み合わせが含まれていたと考えられている[31][34][36][37]。

- 白芷(ビャクシ)

- 草烏(トリカブト)

- 川芎(Ligusticum wallichii)

- 当帰(カラトウキ(Angelica sinensis))

- 烏頭(ハナトリカブトの根茎)

- シロバナヨウシュチョウセンアサガオ

- Mandragora officinarum(マンドレイクの一種)

- ツツジの花

- ジャスミンの根

また、この薬にはハシシ[33]、バングー[32]、商陸[28]、アヘン[38]も含まれていた可能性があると指摘する者もいる。アメリカの中国学者ヴィクター・メアは、麻沸散は「モルヒネ」に関連するインド・ヨーロッパ語の転写であろうとした[39]。華陀は鍼による手術時の鎮痛を発見したのであり、麻沸散は彼の麻酔法とは無関係か、あるいは単に補助的なものであったと考える研究者もいる[40]。多くの医師が歴史的記録に基づいて同じ処方を再現しようと試みているが、華陀のものと同じ臨床効果を達成した医師はいない。いずれにせよ、華陀の処方は大手術には効果がなかったようである[39][41]。

古代から麻酔薬として用いられてきた他の物質には、ビャクシンやコカの抽出物がある[42][43][44]。華佗の学統は途絶えたが、およそ2000年後に同じ東洋の医師、華岡青洲が麻酔薬を開発し、青洲はそれに華佗の処方と同じ、麻沸散と命名することになる[45]。

中世・ルネサンス期

フェルドウスィー(940-1020)はアッバース朝カリフ時代に生きたペルシアの詩人である。彼の民族叙事詩である『シャー・ナーメ』の中で、フェルドウスィーはヒロイン、ルダバに施された帝王切開を描写している。この手術には、ゾロアスター教の司祭が用意した特別なワインが麻酔薬として用いられた[28]。

1020年頃、ペルシアのイブン・スィーナー(980-1037)は『医学典範』の中で、外科手術の際に患者の鼻の下に置く、芳香剤と麻薬が染み込んだスポンジである「催眠スポンジ」について述べている[46][47][48]。アヘンは10世紀から13世紀にかけて、小アジアからヨーロッパ各地に伝わった[49]。

イギリスでは西暦1200年から1500年にかけて、ドウェール(dwale)と呼ばれる薬が麻酔薬として用いられた[50]。このアルコールベースの混合物には、胆汁、アヘン、レタス、ブリオニア(bryony、多年生のつる植物)、ヒヨス、ドクニンジン、酢が含まれていた[50]。外科医は、酢と塩を頬骨にこすりつけることで患者を覚醒させた[50]。シェイクスピアの『ハムレット』やジョン・キーツの詩『ナイチンゲールへの頌歌』など、多くの文学作品にドウェールの記録が見られる[50]。13世紀には、未熟なクワ、亜麻、マンドラゴラの葉、ツタ、レタスの種子、スイバ、ヒヨスの毒汁にスポンジを浸した「睡眠スポンジ」が初めて処方された。処理および/または貯蔵後、スポンジを加熱して蒸気を吸入すると麻酔効果が得られる[要出典]。

後に最初の有効な吸入麻酔薬として用いられることになるジエチルエーテルは、錬金術師のラモン・リュイが、1275年に発見したとされている[50]。パラケルススとして知られるアウレオルス・テオフラストス・ボンバストゥス・フォン・ホーエンハイム(1493-1541)は、1525年頃にジエチルエーテルの鎮痛作用を発見した[51]。1540年、ヴァレリウス・コルドゥスによって初めて合成され、彼はその薬理作用のいくつかに注目した[要出典]。彼はこれをオレウム・デュルチェ・ヴィトリオリ(oleum dulce vitrioli)と呼んだが、これはエタノールと硫酸の混合物(当時はビトリオール(vitriol)油として知られていた)を蒸留することによって合成されるという事実を反映した名前である。ドイツ生まれの化学者アウグスト・ジークムント・フロベニウス(August Sigmund Frobenius)は1730年、この物質にスピリトゥス・ヴィニ・エーテリウス(Spiritus Vini Æthereus)という名前を付けた[52][53]。

18世紀

ジョセフ・プリーストリー(1733~1804)は、亜酸化窒素、一酸化窒素、アンモニア、塩化水素、そして(カール・ヴィルヘルム・シェーレ、アントワーヌ・ラヴォアジエとともに)酸素を発見したイギリスの数学者である。1775年から、プリーストリーは6巻からなる『異なる種類の気体に関する実験と観察(Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air)』を出版した[54]。これに記述された気体や他の気体に関する最近の発見は、ヨーロッパの科学界に大きな関心を呼び起こした。トーマス・ベドーズ(1760-1808)はイギリスの哲学者、医師、医学部教官で、年上の同僚プリーストリー同様、バーミンガムのルナー・ソサエティのメンバーでもあった。この新しい科学をさらに発展させ、これまで治療不可能と考えられていた病気(喘息や結核など)の治療法を提供することを視野に入れ、ベドーズは1798年、ブリストルのクリフトンにあるダウリー・スクエアに、吸入ガス療法のための気体研究所(Pneumatic Institution)を設立した[55]。ベドーズは、化学者であり物理学者でもあったハンフリー・デービー(1778-1829)を研究所の管理責任者として雇い、技術者のジェームズ・ワット(1736-1819)をガスの製造に協力させた。エラズマス・ダーウィンやジョサイア・ウェッジウッドといったルナー・ソサエティの他のメンバーもまた、研究所に積極的に関わっていた。

気体研究所での研究の過程で、デービーは亜酸化窒素に麻酔作用があることを発見した[56]。亜酸化窒素のことを「笑気ガス」と呼ぶようになったデービーは、翌年、現在では古典的な論文となった『主に亜酸化窒素または脱フロギストン空気とその呼吸に関する化学的・哲学的研究』(Researches, chemical and philosophical–chiefly concerning nitrous oxide or dephlogisticated nitrous air, and its respiration)の中で、自分の研究成果を発表した。デービーは医師ではなかったので、手術中に亜酸化窒素を投与したことはなかった。しかし、彼は亜酸化窒素の鎮痛効果と手術中の痛みを和らげる潜在的な利点を最初に記録した人物である[57]。

「亜酸化窒素は、その広範な作用において、肉体的な痛みを破壊することができるようであるので、おそらく、大量に血液が流出することのない外科手術の際に、有利に用いることができるであろう。」

近代医学の始まりとともに、医療において麻酔が実用化されるパラダイムを構築する舞台が整った[58]。

19世紀

琉球・日本

琉球王国首里出身の高嶺徳明は、1689年に琉球(現在の沖縄)で全身麻酔を行ったと伝えられている。彼は1690年に薩摩の医師たちに、1714年には琉球の医師たちにその知識を伝えた[59]。

大坂の華岡青洲(1760-1835)は江戸時代の外科医で、漢方医学の知識と蘭学で学んだ西洋の外科技術を備えていた。1785年頃から、花岡は華陀の麻沸散に似た薬理作用を持つ処方を再び作り出す探求に乗り出した[60]。何年にもわたる研究と実験の末、彼はついに通仙散(別名麻沸散)と名付けた処方を開発した。華陀の処方と同様、この処方は以下の数種類の植物から抽出したエキスで構成されていた[61][62][63]。

通仙散の有効成分は、スコポラミン、ヒヨスチアミン、アトロピン、アコニチン、アンゲリコトキシンである。十分な量を摂取すると、通仙散は全身麻酔と骨格筋の麻痺状態をもたらす[63]。花岡の親友であった中川修亭(1773-1850)は、1796年に『麻薬考』という小冊子を書いた。原本は1867年の火事で失われてしまったが、この冊子には華岡の全身麻酔研究の現状が記されていた[64]。

1804年10月13日、華岡は通仙散を全身麻酔薬として用いて、藍屋勘という60歳の女性の乳癌の乳房部分切除を行った。これは一般に、全身麻酔で行われた手術の最初の確実な記録と見なされている[60][62][65][66][67]。華岡はその後も、悪性腫瘍の切除、膀胱結石の摘出、四肢の切断など、通仙散を用いた多くの手術を行った。1835年に亡くなるまでに、華岡は150例以上の乳癌手術を行った[60][66][68][69]。

欧米

ドイツの薬剤師、フリードリヒ・ゼルチュルナー(1783~1841)は1804年にアヘンからモルヒネを初めて単離した[27]。彼はこれをギリシャ神話の夢の神モルフェウスにちなんでモルフィウムと命名した[70][71]。1817年に今日用いられている名称、モルヒネ(morphine)に改名したのは、フランスの化学者、ゲイ・リュサックである[72]。

イギリスの医師、ヘンリー・ヒル・ヒックマン(Henry Hill Hickman)(1800-1830)は1820年代に麻酔薬として二酸化炭素を用いる実験を行った。彼は動物を二酸化炭素で窒息寸前まで効果的に失神させ、その後四肢の一本を切断して、その効果を調べた。1824年、ヒックマンは研究の結果を『仮死状態に関するレター:人体に対する外科手術の有用性を確認する目的で』という短報にして王立協会に提出した。これに対して1826年、ランセット(Lancet)誌に 『外科的詐欺』と題する論文が掲載され、彼の研究は無慈悲な批判を受けた。ヒックマンは4年後、30歳で亡くなった。亡くなった当時は評価されなかったが、その後、彼の研究は肯定的に再評価され、現在では英国王立医学会によって彼の名を冠した賞とメダルが創設され、麻酔科学上の貢献者に授与されている[73]。

1830年代後半になると、ハンフリー・デービーの実験はアメリカ北東部の学界で広く知られるようになった。放浪する講談師たちは、「エーテル遊び」[74]と呼ばれる大衆集会を開き、観衆のある者達にジエチルエーテルや亜酸化窒素を吸入させ、これらの薬剤の精神に作用する特性を実証するとともに、見物人に多くの娯楽を提供した[75]。このようなイベントに参加し、エーテルがこのように用いられるのを目撃した著名人が4人いる。ウィリアム・エドワード・クラーク(1819-1898)、クロウフォード・ロング (1815-1878)、ホーレス・ウェルズ(1815-1848)、そして ウィリアム・T・G・モートン(1819-1868)である。後年、彼らのある者は、エーテルの麻酔への応用の発明を巡って争うことになり[76]、最初にエーテル麻酔を行ったのが誰か、後世にも議論が起こることになる。

1839年、ニューヨーク州ロチェスターの大学に通っていたクラスメートのクラークとモートンは、定期的にエーテル騒ぎに参加していたようだ[77][78][79][80]。1842年1月、バークシャー医科大学(現ロバートラーナー医科大学)の医学生になっていたクラークが、一女性にエーテルを投与し、その間に抜歯が行われた[78]。こうして彼は、外科的手技を容易にするために吸入麻酔薬を投与した最初の人物となった。クラークは自分の功績をほとんど評価していなかったようで、この技術を発表することも、それ以上追求することもしなかった。実際、この出来事はクラークの伝記にさえ記されていない[81]。

クロウフォード・ロングは、19世紀半ばにジョージア州ジェファーソン市で開業していた医師であり薬剤師であった。1830年代後半、ペンシルベニア大学医学大学院の学生だった彼は、当時流行していたエーテル遊びを観察し、おそらく参加していた。このような集まりでロングは、何人かの参加者にたんこぶやあざができても、その後、彼らが何が起こったのかまったく覚えていないのを観察した。彼は、ジエチルエーテルが亜酸化窒素と同様の薬理効果をもたらすと仮定した。1842年3月30日、彼は、ジェームズ・ヴェナブルという男の首から腫瘍を摘出するために、ジエチルエーテルを吸入させた[82]。ロングはその後、ヴェナブルから2つ目の腫瘍を摘出したが、その際もエーテル麻酔をかけた。さらに彼は、四肢の切断や出産のための全身麻酔薬としてエーテルを使用した。しかし、ロングはその経験を1849年まで発表しなかった。その結果、彼自身が受けるべき名誉の多くを失うことになった[82]。

1844年12月10日、ガードナー・コルトン(Gardner Quincy Colton)はコネチカット州ハートフォードで亜酸化窒素の公開デモンストレーションを行った。参加者の一人が亜酸化窒素の影響下、気づかない間に足に大きな怪我を負った。その日、会場にいたコネチカット州の歯科医ホーレス・ウェルズは、亜酸化窒素のこの明らかな鎮痛効果の重要性をすぐに察知した。翌日、ウェルズはコルトンが投与した亜酸化窒素の影響下で、痛みのない抜歯を受けた。ウェルズはそれから亜酸化窒素を患者に投与するようになり、その後数週間にわたって数回の抜歯を成功させた。

ウィリアム・T・G・モートンもニューイングランドの歯科医で、ウェルズの元教え子であり、その時から当時までウェルズの仕事仲間だった。彼はまた、ウィリアム・エドワード・クラークと面識があり、同級生でもあった(2人はニューヨーク州ロチェスターの大学院で一緒だった)。モートンは、著名な外科医ジョン・コリンズ・ウォーレン(John Collins Warren)と共同で、ウェルズがマサチューセッツ総合病院で亜酸化窒素全身麻酔下での抜歯技術を実演できるよう手配した。だが、1845年1月20日に行われたこのデモンストレーションは、患者が手術の最中に痛みで泣き叫んだため失敗に終わった[83]。

1846年9月30日、モートンは抜歯のため、ボストンの音楽教師エベン・フロストにジエチルエーテルを投与した。その2週間後、モートンはマサチューセッツ総合病院で、今日エーテルドームとして知られている場所で、全身麻酔薬としてジエチルエーテルを用いることを初めて公に実証した[84]。1846年10月16日、ジョン・コリンズ・ウォーレンは、地元の印刷業者エドワード・ギルバート・アボット(Edward Gilbert Abbott)の首から腫瘍を摘出した。手技が終わると、ウォーレンは 「諸君、これは決してインチキではない 」と言ったと伝えられている。この出来事のニュースは瞬く間に世界中を駆け巡った[85]。その年の12月には、スコットランドの外科医ロバート・リストンが最初の四肢切断手術を行った。モートンはその直後に自分の経験を発表した[84]。その後、ハーバード大学のチャールズ・トーマス・ジャクソン(Charles Thomas Jackson)教授(1805-1880)は、モートンが自分のアイデアを盗んだと主張した[86]が、モートンはこれに同意せず、生涯にわたる論争が始まった[85]。長い間、モートンは西半球における全身麻酔の先駆者と信じられていたが、実のところ、彼の実演はクロウフォード・ロングの最初の経験から4年後であった。ロングはその後、当時ジョージア州選出の合衆国上院議員であったウィリアム・クロスビー・ドーソン(William Crosby Dawson)(1798-1856)に、合衆国上院の議場でエーテル麻酔を最初に行ったのは自分であると主張させてくれるよう、請願した[87]。

-

イギリスの産科医、ジェームズ・シンプソン

-

英国の公衆衛生学者・麻酔科医、ジョン・スノウ

1847年、スコットランドのエジンバラの産科医ジェームス・ヤング・シンプソン(1811-1870)が、クロロホルムを全身麻酔薬として初めて人間に用いた(ロバート・モーティマー・グラバー(Robert Mortimer Glover)は1842年にこの可能性について書いていたが、犬にしか用いていなかった)。その後、ヨーロッパではクロロホルム麻酔の使用が急速に拡大した。クロロホルムは20世紀初頭、米国で麻酔薬としてエーテルに取って代わり始めた。しかし、クロロホルムは、その肝毒性と心毒性、特に致命的な不整脈を引き起こす傾向が明らかになると、またすぐにエーテルに取って代わられた。実際のところは、主要な麻酔ガスとしてクロロホルムを用いるかエーテルを用いるかは、国や地域によって異なっていた。たとえば、イギリスとアメリカ南部はクロロホルムにこだわり、アメリカ北部はエーテルに戻った[58]。ジョン・スノウはすぐに、エーテルとクロロホルムという新しい麻酔ガスを扱う最も経験豊富な英国人医師となり、事実上、英国初の麻酔科医となった。入念な臨床記録を通じて、彼はやがてロンドン医学界のエリートたちに、クロロホルム麻酔が出産において正当な位置を占めることを納得させることができた。こうして1853年、ヴィクトリア女王の侍女たちは、ジョン・スノウを女王の8人目の子供の出産の麻酔に招いた[88]。エーテルとクロロホルムの麻酔が始まってから20世紀に至るまで、標準的な麻酔薬の投与方法は開放点滴法、であった。つまり、マスクを患者の口に当て、その中に布を入れて、患者が自然に呼吸する状態で揮発性の液体をマスクに滴下した。後に安全な気管チューブが開発されると、この方法は変わった[89]。ロンドンの医療は独特の社会的環境であったため、19世紀末には麻酔が独自の専門分野となったが、英国の他の地域や世界のほとんどの地域では、麻酔は外科医の権限下にあり、外科医はその仕事を下級医師や看護師に任せていた[58]。アメリカで麻酔科が独立部門となるには1936年まで待たねばならなかった[90]

オーストリアの外交官カール・フォン・シェルツァー(Karl von Scherzer)がペルーから十分な量のコカの葉を持ち帰った後、1860年にアルバート・ニーマン(Albert Niemann)がコカインを単離し[91]、これが最初の局所麻酔薬となった[92][93][94]。

1871年、ドイツの外科医フリードリヒ・トレンデレンブルク(Friedrich Trendelenburg)(1844~1924年)が、全身麻酔を目的とした待機的気管切開を初めて成功させたという論文を発表した[95][96]。

1880年には、スコットランドの外科医ウィリアム・メイスウェン(William Macewen)(1848-1924)が、声門浮腫のある患者に呼吸を可能にするために、気管切開の代替として、またクロロホルムを用いた全身麻酔の際に、気管挿管を用いたことを報告している[97][98][99]。1895年4月23日、ドイツのアルフレッド・キルシュタイン(Alfred Kirstein, 1863-1922)が声帯の直接可視化(喉頭展開)を初めて報告するまで、それまでの声門と喉頭の観察(マヌエル・ガルシア(Manuel García)[100]、ヴィルヘルム・ハック(Wilhelm Hack)[101][102]、メイスウェンなど)はすべて、鏡を用いた間接観察で行われていた。キルシュタインはこの目的のために改造した食道鏡(オートスコープと命名された)を用いて、ベルリンで最初の直接喉頭展開を行った[103]。皇帝フリードリヒ3世(1831-1888)の死[104]が、キルシュタインがオートスコープを開発する動機となった可能性があるとされる[105]。

20世紀

20世紀には、気管切開、内視鏡、気管挿管といった手技が、めったに行われないものから、麻酔、集中治療、救急医療、消化器病学、呼吸器病学、外科の診療に不可欠な要素へと変貌を遂げた。

1902年、ドイツの化学者、エミール・フィッシャー(Hermann Emil Fischer, 1852-1919)とジョセフ・フォン・メリング(Joseph von Mering)(1849-1908)は、ジエチルバルビツール酸が効果的な睡眠薬であることを発見した[106]。バルビタールまたはベロナール(バイエル薬品が命名した商品名)とも呼ばれるこの新薬は、商業的に販売された最初のバルビツール酸となり、1903年から1950年代半ばまで不眠症の治療薬として用いられた。しかし、この系統の薬剤から、今日でも用いられている短時間作用性麻酔薬チオペンタールが開発されるのには30年以上待たねばならなかった[107]。1913年まで、口腔および顎顔面外科手術は、マスク吸入麻酔、局所麻酔薬の粘膜への表面麻酔、直腸麻酔、または静脈麻酔によって行われていた。これらの麻酔法は有効ではあったが、気道の閉塞から守ることはできず、血液や粘液が気管や気管支に吸引される危険に患者をさらすものであった。1913年、シュバリエ・ジャクソン(Chevalier Jackson)(1865-1958)が、気管挿管の手段として直接喉頭展開を行って高い成功率を報告した最初の人物である[108]。ジャクソンは、キルシュタインが用いた操作者側の光源ではなく、器具の患者側の先端に光源を持つ新しい喉頭鏡のブレードを導入した[109]。この新しいブレードには、気管チューブや気管支鏡を通すスペースを確保するために、操作者がスライドできる部品が組み込まれていた[110]。

また1913年には、ヘンリー・H・ジェインウェイ(Henry H. Janeway)(1873-1921)が、最近開発した喉頭鏡を用いて達成した結果を発表した[111]。ニューヨークのベルビュー病院(Bellevue Hospital)で開業していた麻酔科医のジェインウェイは、揮発性麻酔薬を直接気管内に送気すれば、耳鼻咽喉科手術の条件が改善されると考えていた。そこで彼は、気管挿管専用の喉頭鏡を開発した。ジャクソンの器具と同様、ジェインウェイの装置にも遠位光源が組み込まれていた。しかし、ユニークな点は、ハンドルに電池が内蔵されていること、挿管中に気管チューブを口腔咽頭の正中線に維持するためにブレードの中央に切り欠きがあること、チューブを声門に導くためにブレードの先端がわずかにカーブしていることであった。この設計が成功したことで、その後、他の種類の手術にも用いられるようになった。こうしてジェインウェイは、麻酔科診療における直接喉頭展開と気管挿管の普及に貢献した[105]。

-

カフ付き気管チューブ

-

気管チューブ留置のイラスト

1928年、アーサー・アーネスト・ゲデル(Arthur Ernest Guedel)は、カフ付き気管内チューブを臨床に導入した。このチューブは、自発呼吸を完全に抑制する深い麻酔を可能にする一方、麻酔科医が制御する陽圧換気によって麻酔ガスと酸素を患者に供給するものであった[112]。わずか3年後、ジョセフ・W・ゲイル(Joseph W. Gale)が、麻酔科医が一度に片方の肺だけを人工呼吸できる技術、すなわち分離肺換気を開発した[113]。これによって、それまで胸郭が大気に開放されているために胸腔内の陰圧が失われ、患者の呼気によって手術最中の肺が膨らんでしまうペンデルフト(Pendelluft)現象に悩まされていた胸部外科手術が発展することになった[114]。やがて1980年代初頭には、透明プラスチック製のダブルルーメンチューブが登場した。フレキシブルな光ファイバー気管支鏡を用いてこのチューブを適切な位置に留置し、麻酔科医が片方の肺を選択的に換気しながら、手術する側の肺の気管支を遮断し、安静術野の提供が可能となった[89]。現代麻酔科学に不可欠なのは麻酔器である。初期の装置のひとつであるカッパーケテルは、ウィスコンシン大学のルシアン・E・モリス(Lucien E. Morris)によって開発された[115][116]。

最初の静脈麻酔薬であるチオペンタールナトリウムは、アボット・ラボラトリーズのアーネスト・ボルワイラー(Ernest H. Volwiler)(1893-1992)とドナリー・L・タバーン(Donalee L. Tabern, 1900-1974)によって1934年に合成された[107]。この薬は1934年3月8日、ラルフ・M・ウォーターズ(Ralph M. Waters)がその特性を調査するために初めてヒトに用いたが、その特性は短時間の麻酔作用であり、鎮痛作用は驚くほど少なかった。その3ヵ月後、ジョン・サイラス・ランディ(John Silas Lundy)がアボットラボラトリーズの依頼を受け、メイヨークリニックでチオペンタールの臨床試験を開始した。ヴォルワイラーとタバーンはチオペンタールの発見により、1939年に米国特許第2,153,729号を取得し、1986年に全米発明家殿堂に名を連ねた。

1939年、アトロピンの代用となる合成薬の探索は、偶然にもモルヒネとは全く異なる構造を持つ最初のオピオイドであるメペリジンの発見へと結実した[117]。続いて1947年には、モルヒネと薬理学的特性が類似するものの、構造的に無関係な化合物であるメサドンが広く用いられるようになった[118]。

第一次世界大戦後、気管内麻酔法の分野でさらなる進歩があった。中でもイヴァン・マギル(Ivan Magill)(1888-1986)の功績は大きかった。イギリスのシドカップ(Sidcup)の顔面・顎外傷専門のクイーンズ病院(Queen's Hospital for Facial and Jaw Injuries)で、形成外科医のハロルド・ギリーズ(Harold Gillies)(1882-1960)、麻酔医のE.スタンレー・ロウボサム(E. Stanley Rowbotham、1890-1979)と共に働いていたマギルは、意識下盲目的盲経鼻気管挿管の手技を開発した[119][120][121][122][123][124]。マギルは、角度のついた新型の鉗子(マギル鉗子)も考案した[125]。これは、マギルが報告した当初の手技とほとんど変わらない方法で、経鼻気管挿管を容易にするために現在も用いられている[125]。マギルが発明したその他の器具には、マギル喉頭鏡のブレード[126]や、揮発性麻酔薬を投与するためのいくつかの器具がある[127][128][129]。気管チューブの弯曲(Magill curve)もマギルにちなんで命名されたものである。

最初の病院内の麻酔科は、ヘンリー・ビーチャー(Henry Beecher)(1904–1976)の指導の下、1936年にマサチューセッツ総合病院に設立された。しかし、外科で訓練を受けたビーチャーに麻酔の経験はなかった[90]。

筋弛緩剤クラーレは当初、精神疾患への電気けいれん療法に伴う合併症の痙攣を軽減するために用いられたが、1940年代にE.M.パッパー( E.M. Papper)とスチュアート・カレン(Stuart Cullen)がスクイブ社(ブリストル・マイヤーズ・スクイブ社の前身)製の製剤を用いてニューヨークのベルビュー病院の手術室で用いるようになった[130]。この神経筋遮断薬によって横隔膜の完全麻痺が可能となり、陽圧換気による人工呼吸器による調節呼吸が可能となった[89]。陽圧換気が一般的に使われるようになったのは、1950年代のポリオの流行がきっかけであり、特にデンマークでは1952年に大流行し、麻酔科学から集中治療医学が誕生する契機となった。当初、麻酔科医は必要な場合を除き、人工呼吸器を手術室に持ち込むことをためらっており、1960年代までは標準的な手術室設備にはならなかった[89]。

ロバート・マッキントッシュ(Robert Macintosh)(1897-1989)は、1943年に新しい曲型喉頭鏡のブレードを発表し、気管挿管の技術を大きく進歩させた[131]。マッキントッシュ型ブレードは、今日でも気管挿管に最も広く用いられている喉頭鏡のブレードである[132]。1949年、マッキントッシュは気管内挿管を容易にするため、天然ゴム製の尿道カテーテルを気管挿管時のガイド(イントロデューサー)として用いた症例報告を発表した(ガムエラスティックブジーの原型)[133]。マッキントッシュの報告に触発されたヘックス・ヴェン(P. Hex Venn)が、このコンセプトに基づく気管チューブイントロデューサーの開発に着手した。ヴェンのデザインは1973年3月に採用され、Eschmann気管チューブイントロデューサーとして後に知られるようになったものが、その年の後半に生産が開始された[134]。ヴェンの設計の素材は、ポリエステル糸で織られたチューブの芯と外側の天然樹脂層の2層になっている点で、ガムエラスティックブジーとは異なっていた。これにより、剛性は増したが、柔軟性と気管チューブを操作するための滑らかな表面は維持された。その他の違いとしては、長さ(新型イントロデューサーは60cmで、ガムエラスティックブジーよりはるかに長い)と、先端が35度湾曲しており、口腔・咽頭内の障害物を避けて使用できることが挙げられる[135][136]。

-

ジエチルエーテル

-

セボフルラン

100年以上の間、吸入麻酔薬の主流は1930年代に導入されたシクロプロパンとエーテルのままであった。これらはいずれも引火しやすかった。1956年には、引火性がないという大きな利点を持つハロタンが導入された[137]。これにより、手術室火災のリスクが減少した。1960年代には、まれにではあるが、ハロタンに不整脈や肝毒性といった重大な副作用が出たため、ハロゲン化エーテルがハロタンに取って代わった。最初の2種類のハロゲン化エーテルはメトキシフルランとエンフルランであった。これらは更に1980年代から1990年代にかけて、現在の標準であるイソフルラン、セボフルラン、デスフルランに取って代わられたが、オーストラリアではメトキシフルランがペンスロックス(商品名、Penthrox)として病院前救護の麻酔に用いられている[138]。 ハロタンは、発展途上国の多くで依然用いられている[139]。

20世紀後半には、多くの新しい静脈麻酔薬やオピオイドが開発され、臨床で用いられるようになった。ヤンセンファーマの創設者であるポール・ヤンセン(Paul Janssen)(1926-2003)は、80種類以上の医薬化合物を開発したことで知られている[140]。ヤンセンはハロペリドール(1958年)とドロペリドール(1961年)[141]に始まるブチロフェノン系の抗精神病薬のほとんどすべてを合成した。これらの抗精神病薬は急速に麻酔の実践に組み込まれた[142][143][144][145][146]。

1960年、ヤンセンの研究チームは、ピペリジノン(piperidinone)誘導体の最初のオピオイドであるフェンタニルを合成した[147][148]。フェンタニルに続いて、スフェンタニル(1974年)[149]、アルフェンタニル(1976年)[150][151]、カルフェンタニル(1976年)[152]、ロフェンタニル(1980年)[153]が開発された。ヤンセンらのチームは、強力な静脈麻酔薬であるエトミデート(1964年)も開発した[154]。

気管挿管にファイバー内視鏡を用いるというコンセプトは、1967年にイギリスの麻酔科医ピーター・マーフィー(Peter Murphy)によって導入された[155]。1980年代半ばまでに、軟性のファイバー気管支鏡は、呼吸器科や麻酔科の分野では欠くことのできない器械となった[156][157]。

21世紀

21世紀の情報化時代において、気管挿管の技術と理論は進歩した。CMOSアクティブ・ピクセル・センサ(APS)などのデジタル技術を採用したビデオ喉頭鏡がいくつかのメーカーから開発され、気管挿管時に声門が画面で確認できるようになっている。ビデオ喉頭鏡グライドスコープはその一例である[158][159]。

脚注

注釈

出典

- ^ a b c 松木明知. “「麻酔」の語史学的研究”. 2023年2月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年12月25日閲覧。

- ^ “麻酔に関する説明書 2018 年 3 月版(中文/中国語)”. 厚生労働省. 2023年12月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Haridas, Rajesh P. (1 November 2017). “Earliest English Definitions of Anaisthesia and Anaesthesia”. Anesthesiology 127 (5): 747–753. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001764. PMID 28654424.

- ^ ἀναισθησία. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Small, MR (1962). Oliver Wendell Holmes. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8084-0237-4. OCLC 273508. "In a letter to dentist William T. G. Morton, Holmes wrote: "Everybody wants to have a hand in a great discovery. All I will do is to give a hint or two as to names—or the name—to be applied to the state produced and the agent. The state should, I think, be called 'Anaesthesia.' This signifies insensibility—more particularly ... to objects of touch.""

- ^ Haridas, R. P. (July 2016). “The etymology and Use of the Word 'Anaesthesia': Oliver Wendell Holmes' Letter to W. T. G. Morton”. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44: 38–44. doi:10.1177/0310057X1604401S07. PMID 27456290.

- ^ Powell MA (2004). “9: Wine and the vine in ancient Mesopotamia: the cuneiform evidence”. The Origins and Ancient History of Wine. Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology. 11 (1 ed.). Amsterdam: Taylor & Francis. pp. 96–124. ISBN 9780203392836. ISSN 0275-5769 2010年9月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Perioperative uses of intravenous opioids: Specific agents”. UpToDate. 2023年12月17日閲覧。

- ^ Evans, TC (1928). “The opium question, with special reference to Persia (book review)”. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 21 (4): 339–340. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(28)90031-0 2010年9月18日閲覧. "The earliest known mention of the poppy is in the language of the Sumerians, a non-Semitic people who descended from the uplands of Central Asia into Southern Mesopotamia...."[リンク切れ]

- ^ Booth M (1996). “The discovery of dreams”. Opium: A History. London: Simon & Schuster, Ltd.. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-312-20667-3 2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Krikorian, AD (March 1975). “Were the opium poppy and opium known in the ancient Near East?”. Journal of the History of Biology 8 (1): 95–114. doi:10.1007/BF00129597. PMID 11609871.

- ^ Kramer, SN (March 1954). “First pharmacopeia in man's recorded history”. American Journal of Pharmacy and the Sciences Supporting Public Health 126 (3): 76–84. ISSN 0002-9467. PMID 13148318.

- ^ History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History (3 ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. (March 1988). ISBN 978-0-8122-1276-1

- ^ a b “II: Development of the problem”. The Opium Problem. New York: Bureau of Social Hygiene. (1928). p. 54 2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Sonnedecker G (1962). “Emergence of the Concept of Opiate Addiction”. Journal Mondial de Pharmacie 3: 275–290. ISSN 0021-8405.

- ^ a b c “The pattern of man's use of narcotic drugs”. The Traffic in Narcotics. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. (1953). p. 1. ISBN 978-0-405-13567-5 2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Thompson RC (July 1926). “The Assyrian herbal: a monograph on the Assyrian vegetable drugs”. Isis 8 (3): 506–508. doi:10.1086/358424. JSTOR 223920. "Thompson reinforces his view with the following quotation from a cuneiform tablet: 'Early in the morning old women, boys, and girls collect the juice, scraping it off the notches (of the poppy-capsule) with a small iron blade, and place it within a clay receptacle.'"

- ^ Sullivan, R (August 1996). “The identity and work of the ancient Egyptian surgeon”. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 89 (8): 467–73. doi:10.1177/014107689608900813. PMC 1295891. PMID 8795503.

- ^ a b Ludwig Christian Stern 著、Ebers G 編(ドイツ語)『Papyrus Ebers』 2巻(1版)、Bei S. Hirzel、Leipzig、1889年。OCLC 14785083。2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Pahor, AL (August 1992). “Ear, nose and throat in ancient Egypt: Part I”. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 106 (8): 677–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100120560. PMID 1402355.

- ^ Ebbell B (1937). The Papyrus Ebers: The greatest Egyptian medical document. Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard. オリジナルの26 February 2005時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Was opium known in 18th Dynasty ancient Egypt? An examination of materials from the tomb of the chief royal architect Kha”. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 41 (1–2): 99–114. (January 1994). doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90064-7. PMID 8170167.

- ^ “The history of the poppy and of opium and their expansion in antiquity in the eastern Mediterranean area”. Bulletin on Narcotics 19 (3): 17–38. (1967). ISSN 0007-523X. オリジナルの2011-07-28時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月18日閲覧。.

- ^ Sushruta 著「Introduction」、Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna 編『Sushruta Samhita, Volume1: Sutrasthanam』Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna、Calcutta、1907年、iv頁。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Dwarakanath SC (1965). “Use of opium and cannabis in the traditional systems of medicine in India”. Bulletin on Narcotics 17 (1): 15–9. ISSN 0007-523X. オリジナルの2011-07-28時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月27日閲覧。.

- ^ Fort J (1965). “Giver of delight or Liberator of sin: Drug use and "addiction" in Asia”. Bulletin on Narcotics 17 (3): 1–11. ISSN 0007-523X. オリジナルの2011-07-28時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月27日閲覧。.

- ^ a b Meyer, K (2004年). “Dem Morphin auf der Spur” (ドイツ語). Pharmazeutischen Zeitung. GOVI-Verlag. 2012年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Gordon BL (1949). Medicine throughout Antiquity (1 ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. pp. 358, 379, 385, 387. ISBN 9780598609977. OCLC 1574261 2010年9月14日閲覧. "Pien Chiao (ca. 300 BC) used general anesthesia for surgical procedures. It is recorded that he gave two men, named "Lu" and "Chao", a toxic drink which rendered them unconscious for three days, during which time he performed a gastrotomy upon them"

- ^ Giles L (transl.)『Taoist teachings from the book of Lieh-Tzŭ, translated from the Chinese, with introduction and notes, by Lionel Giles (Wisdom of the East series)』John Murray、London、1912年。2010年9月14日閲覧。

- ^ Salguero, CP (February 2009). “The Buddhist medicine king in literary context: reconsidering an early medieval example of Indian influence on Chinese medicine and surgery”. History of Religions 48 (3): 183–210. doi:10.1086/598230. ISSN 0018-2710.

- ^ a b c d e f Chu NS (December 2004). “Legendary Hwa Tuo's surgery under general anesthesia in the second century China” (中国語). Acta Neurologica Taiwanica 13 (4): 211–6. ISSN 1028-768X. PMID 15666698. オリジナルの26 February 2012時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月18日閲覧。.

- ^ a b Giles L (transl.) 著、Cranmer-Byng JL 編『A Gallery of Chinese immortals: selected biographies, translated from Chinese sources by Lionel Giles (Wisdom of the East series)』(1版)John Murray、London、1948年。2010年9月14日閲覧。"The well-attested fact that Hua T'o made use of an anaesthetic for surgical operations over 1,600 years before Sir James Simpson certainly places him to our eyes on a pinnacle of fame...."。

- ^ a b Giles HA『A Chinese Biographical Dictionary』Bernard Quaritch、London、1898年、323–4, 762–3頁。ISBN 9780896440104。2010年9月14日閲覧。"If a disease seemed beyond the reach of needles and cautery, he operated, giving his patients a dose of hashish which rendered them unconscious."。

- ^ a b Chen J (August 2008). “A Brief Biography of Hua Tuo”. Acupuncture Today 9 (8). ISSN 1526-7784.

- ^ 松木明知「麻酔科学史研究最近の知見(23)一 華佗の麻酔法と大麻の分布に関連して一」『麻酔』第34巻、1985年、375-379頁。

- ^ Wang Z; Ping C (1999). “Well-known medical scientists: Hua Tuo”. In Ping C. History and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 1. Beijing: Science Press. pp. 88–93. ISBN 978-7-03-006567-4 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Fu LK (August 2002). “Hua Tuo, the Chinese god of surgery”. Journal of Medical Biography 10 (3): 160–6. doi:10.1177/096777200201000310. PMID 12114950. オリジナルの19 July 2009時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ Huang Ti Nei Ching Su Wen: The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. (1972). p. 265. ISBN 978-0-520-02158-7

- ^ a b Ch'en S 著「The Biography of Hua-t'o from the History of the Three Kingdoms」、Mair VH 編『The shorter Columbia anthology of traditional Chinese literature』 Part III: Prose、Columbia University Press、New York、2000年、441–9頁。ISBN 978-0-231-11998-6。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Lu GD; Needham J (2002). “Acupuncture and major surgery”. Celestial lancets: a history and rationale of acupuncture and moxa. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 218–30. ISBN 978-0-7007-1458-2 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Wai, FK (2004). “On Hua Tuo's Position in the History of Chinese Medicine”. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 32 (2): 313–20. doi:10.1142/S0192415X04001965. PMID 15315268.

- ^ Carroll E. (1997). “Coca: the plant and its use”. In Robert C. Petersen; Richard C. Stillman. Cocaine: 1977. United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. p. 35. オリジナルの4 November 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。 2014年11月3日閲覧。

- ^ Peterson, RC (1997). “History of Cocaine”. In Robert C. Petersen; Richard C. Stillman. Cocaine: 1977. United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. pp. 17–32. オリジナルの4 November 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月16日閲覧。

- ^ Rivera MA; Aufderheide AC; Cartmell LW; Torres CM; Langsjoen O (December 2005). “Antiquity of coca-leaf chewing in the south central Andes: a 3,000 year archaeological record of coca-leaf chewing from northern Chile”. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 37 (4): 455–8. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10399820. PMID 16480174.

- ^ Maltby 2016, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Skinner, P (2008). "Unani-tibbi". In Laurie J. Fundukian (ed.). The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine (3rd ed.). Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale. ISBN 978-1-4144-4872-5. 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Ajram K (1992). Miracle of Islamic Science (1 ed.). Vernon Hills, IL: Knowledge House Publishers. pp. Appendix B. ISBN 978-0-911119-43-5 2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Hunke S(ドイツ語)『Allahs Sonne über dem Abendland: unser arabisches Erbe』(2版)Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt、Stuttgart、1960年、279–80頁。ISBN 978-3-596-23543-8。2010年9月13日閲覧。"The science of medicine has gained a great and extremely important discovery and that is the use of general anaesthetics for surgical operations, and how unique, efficient, and merciful for those who tried it the Muslim anaesthetic was. It was quite different from the drinks the Indians, Romans and Greeks were forcing their patients to have for relief of pain. There had been some allegations to credit this discovery to an Italian or to an Alexandrian, but the truth is and history proves that, the art of using the anaesthetic sponge is a pure Muslim technique, which was not known before. The sponge used to be dipped and left in a mixture prepared from cannabis, opium, hyoscyamus, and a plant called Zoan."。

- ^ “The History of the Poppy and of Opium and Their Expansion in Antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean Area”. Bulletin on Narcotics 19 (4): 5–10. (1967). ISSN 0007-523X.

- ^ a b c d e Carter, Anthony J. (18 December 1999). “Dwale: an anaesthetic from old England”. BMJ 319 (7225): 1623–1626. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1623. PMC 1127089. PMID 10600971.

- ^ Gravenstein JS (November–December 1965). “Paracelsus and his contributions to anesthesia”. Anesthesiology 26 (6): 805–11. doi:10.1097/00000542-196511000-00016. PMID 5320896.

- ^ Frobenius, AS (1 January 1729). “An Account of a Spiritus Vini Æthereus, Together with Several Experiments Tried Therewith”. Philosophical Transactions 36 (413): 283–9. doi:10.1098/rstl.1729.0045.

- ^ Mortimer, C; Mortimer, C. (1 January 1739). “Abstracts of the Original Papers Communicated to the Royal Society by Sigismond Augustus Frobenius, M. D. concerning His Spiritus Vini Aethereus: Collected by C. Mortimer, M. D. Secr. R. S”. Philosophical Transactions 41 (461): 864–70. Bibcode: 1739RSPT...41..864F. doi:10.1098/rstl.1739.0161.

- ^ Priestley J『Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air』 1巻(2版)、J. Johnson、London、1775年、108–29, 203–29頁。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Levere, TH (July 1977). “Dr. Thomas Beddoes and the establishment of his Pneumatic Institution: a tale of three presidents”. Notes and Records of the Royal Society 32 (1): 41–9. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1977.0005. JSTOR 531764. PMID 11615622.

- ^ Sneader W (2005). “Chapter 8: Systematic medicine”. Drug discovery: a history. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 78–9. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Davy H『Researches, chemical and philosophical–chiefly concerning nitrous oxide or dephlogisticated nitrous air, and its respiration』Biggs and Cottle、Bristol、1800年。2010年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Snow, Stephanie (2005). Operations without pain: the practice and science of anaesthesia in Victorian Britain. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-333-71492-8

- ^ Arashiro Toshiaki, Ryukyu-Okinawa Rekishi Jinbutusuden OkinawaJijishuppan, 12006. pp. 66–68

- ^ a b c Izuo, M (November 2004). “Medical history: Seishū Hanaoka and his success in breast cancer surgery under general anesthesia two hundred years ago”. Breast Cancer 11 (4): 319–24. doi:10.1007/BF02968037. PMID 15604985.

- ^ Ogata T (November 1973). “Seishu Hanaoka and his anaesthesiology and surgery”. Anaesthesia 28 (6): 645–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1973.tb00549.x. PMID 4586362.

- ^ a b Hyodo M (1992). “Doctor S. Hanaoka, the world's-first success in providing general anesthesia”. The Pain Clinic IV: proceedings of the fourth international symposium. Utrecht, Netherlands: VSP. pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-90-6764-147-0 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b van D., JH (2010年). “Chosen-asagao and the recipe for Hanaoka's anesthetic 'tsusensan'”. Brighton, UK: BLTC Research. 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ 松木明知「中川修亭の『麻薬考』の書誌学的研究 4種の写本の検討」『日本医史学雑誌』第45巻第4号、1999年12月、585–99頁、ISSN 0549-3323、PMID 11624281、 オリジナルの2012年3月13日時点におけるアーカイブ、2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Perrin, N『Giving up the gun: Japan's reversion to the sword, 1543–1879』David R. Godine、Boston、1979年、86頁。ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b Matsuki A (September 2000). “New studies on the history of anesthesiology—a new study on Seishū Hanaoka's "Nyugan Ckiken Roku" (a surgical experience with breast cancer)”. Masui 49 (9): 1038–43. ISSN 0021-4892. PMID 11025965 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ “医学・医療の電子コンテンツ配信サービス”. 医書ジェーピー. doi:10.11477/mf.1408101987. 2023年12月17日閲覧。

- ^ Tominaga, T (30 December 1994). “Presidential address: Newly established Japanese breast cancer society and the future”. Breast Cancer 1 (2): 69–78. doi:10.1007/BF02967035. PMID 11091513.

- ^ Matsuki A「A Study on Seishu Hanaoka's Nyugan Seimei Roku (Scroll of Diseases): A Name List of Breast Cancer Patients」『Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi』第48巻第1号、2002年3月、53–65頁、ISSN 0549-3323、PMID 12152628、 オリジナルの2012年3月13日時点におけるアーカイブ、2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Drugs and Drug Policy: The Control of Consciousness Alteration. SAGE Publications. (2013). p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4833-2188-2. オリジナルの8 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Sertürner coined the term morphium in: Sertuerner (1817) "Ueber das Morphium, eine neue salzfähige Grundlage, und die Mekonsäure, als Hauptbestandtheile des Opiums" (On morphine, a new salifiable [i.e., precipitable], fundamental substance, and meconic acid, as principal components of opium), Annalen der Physik, 55 : 56–89. It was Gay-Lussac, a French chemist and editor of Annales de Chimie et de Physique, who coined the word morphine in a French translation of Sertuener's original German article: Sertuener (1817) "Analyse de l'opium: De la morphine et de l'acide méconique, considérés comme parties essentielles de l'opium" (Analysis of opium: On morphine and on meconic acid, considered as essential constituents of opium), Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 2nd series, 5 : 21–42. From p. 22: " ... car il a pris pour cette substance, que j'appelle morphine (morphium), ce qui n'en était qu'une combinaison avec l'acide de l'opium." ( ... for he [i.e., French chemist and pharmacist Charles Derosne (1780–1846)] took as that substance [i.e., the active ingredient in opium], which I call "morphine" (or morphium), what was only a compound of it with acid of opium.)

- ^ Sertuerner, F.W. (1817). “De la morphine et de l’acide meconique, consideres comme parties essentielles de l’opium.”. Annales de Chimie et de Physique 5: 21–42.

- ^ “Hickman Medal” (英語). Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology. 2023年12月11日閲覧。

- ^ 松木明知 1998, p. 5.

- ^ “The Discovery of Modern Anaesthesia–Contributions of Davy, Clarke, Long, Wells, and Morton”. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia 51 (6): 472–8. (2007). ISSN 0019-5049.

- ^ 松木明知 1998, pp. 12, 16.

- ^ Sims JM (1877). “The Discovery of Anaesthesia”. Virginia Medical Monthly 4 (2): 81–100.

- ^ a b Lyman HM (1881). “History of anaesthesia”. Artificial anaesthesia and anaesthetics. New York: William Wood and Company. p. 6 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Lyman HM (September 1886). “The discovery of anesthesia”. Virginia Medical Monthly 13 (6): 369–92 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ Richmond PA (1950). “Was William E. Clarke of Rochester the first American to use ether for surgical anesthesia?”. Genesee County Scrapbook of the Rochester Historical Society 1: 11–3.

- ^ Stone RF (1898). Stone RF. ed. Biography of Eminent American Physicians and Surgeons (2 ed.). Indianapolis: CE Hollenbeck. p. 89 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b Long CW (December 1849). “An account of the first use of Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation as an Anaesthetic in Surgical Operations”. Southern Medical and Surgical Journal 5: 705–13. reprinted in Long, C. W. (December 1991). “An account of the first use of Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation as an Anaesthetic in Surgical Operations”. Survey of Anesthesiology 35 (6): 375. doi:10.1097/00132586-199112000-00049.

- ^ Wells, H『A History of the Discovery of the Application of Nitrous Oxide Gas, Ether, and Other Vapors to Surgical Operations』J. Gaylord Wells、Hartford、1847年。2010年9月13日閲覧。"Horace Wells."。

- ^ a b Morton, WTG『Remarks on the Proper Mode of Administering Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation』Button and Wentworth、Boston、1847年。OCLC 14825070。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b Fenster, JM (2001). Ether Day: The Strange Tale of America's Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019523-6

- ^ Jackson CT『A Manual of Etherization: Containing Directions for the Employment of Ether』J.B. Mansfield、Boston、1861年。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Northen WJ; Graves JT (1910). Men of Mark in Georgia: A Complete and Elaborate History of the State from Its Settlement to the Present Time, Chiefly Told in Biographies and Autobiographies of the Most Eminent Men of Each Period of Georgia's Progress and Development. 2. Atlanta, Georgia: A.B. Caldwell. pp. 131–136

- ^ Caton, D (2000). “John Snow's practice of obstetric anesthesia”. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 92 (1): 247–52. doi:10.1097/00000542-200001000-00037. PMID 10638922.

- ^ a b c d Brodsky, J; Lemmens, H (2007). “The history of anesthesia for thoracic surgery”. Minerva Anestesiologica 73 (10): 513–24. PMID 17380101.

- ^ a b Gravenstein, Joachim (January 1998). “Henry K. Beecher: The Introduction of Anesthesia into the University”. Anesthesiology 88 (1): 245–253. doi:10.1097/00000542-199801000-00033. PMID 9447878.

- ^ Niemann, A (1860). Uber eine Neue Organische Base in den Cocablättern [thesis]. Göttingen.

- ^ Wawersik, J (May–June 1991). “History of anesthesia in Germany”. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 3 (3): 235–244. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(91)90167-L. PMID 1878238 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ Bain, JA; Spoerel, WE (November 1964). “Observation on the use of cuffed tracheostomy tubes (with particular reference to the James tube)”. Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal 11 (6): 598–608. doi:10.1007/BF03004104. PMID 14232175.

- ^ Reutsch, Y; Boni, T; Borgeat, A (2001). “From cocaine to ropivacaine: the history of local anesthetic drugs”. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 1 (3): 175–182. doi:10.2174/1568026013395335. PMID 11895133.

- ^ Trendelenburg, F (1871). “Beiträge zu den Operationen an den Luftwegen [Contributions to airways surgery]” (ドイツ語). Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie 12: 112–33.

- ^ Hargrave, R (June 1934). “Endotracheal Anæsthesia in Surgery of the Head and Neck”. Canadian Medical Association Journal 30 (6): 633–7. PMC 403396. PMID 20319535.

- ^ Macewen, W (July 1880). “General Observations on the Introduction of Tracheal Tubes by the Mouth, Instead of Performing Tracheotomy or Laryngotomy”. British Medical Journal 2 (1021): 122–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1021.122. PMC 2241154. PMID 20749630.

- ^ Macewen, W (July 1880). “Clinical Observations on the Introduction of Tracheal Tubes by the Mouth, Instead of Performing Tracheotomy or Laryngotomy”. British Medical Journal 2 (1022): 163–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1022.163. PMC 2241109. PMID 20749636.

- ^ Macmillan, M (May 2010). “William Macewen [1848–1924]”. Journal of Neurology 257 (5): 858–9. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5524-5. PMID 20306068.

- ^ García, M (24 May 1855). “Observations on the Human Voice”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 7 (60): 399–410. Bibcode: 1854RSPS....7..399G. doi:10.1098/rspl.1854.0094. PMC 5180321. PMID 30163547 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ Hack, W (1878). “Über die mechanische Behandlung der Larynxstenosen [On the mechanical treatment of laryngeal stenosis]” (ドイツ語). Sammlung Klinischer Vorträge 152: 52–75.

- ^ Hack, W (March 1878). “Über einen fall endolaryngealer exstirpation eines polypen der vorderen commissur während der inspirationspause” (ドイツ語). Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift: 135–7 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ Hirsch, NP; Smith, GB; Hirsch, PO (January 1986). “Alfred Kirstein. Pioneer of direct laryngoscopy”. Anaesthesia 41 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb12702.x. PMID 3511764.

- ^ Mackenzie, M『The case of Emperor Frederick III.: full official reports by the German physicians and by Sir Morell Mackenzie』Edgar S. Werner、New York、1888年、276頁。2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b Burkle, CM; Zepeda, FA; Bacon, DR; Rose, SH (April 2004). “A Historical Perspective on Use of the Laryngoscope as a Tool in Anesthesiology”. Anesthesiology 100 (4): 1003–6. doi:10.1097/00000542-200404000-00034. PMID 15087639.

- ^ Fischer EH; Mering J (March 1903). “Ueber eine neue Klasse von Schlafmitteln” (ドイツ語). Die Therapie der Gegenwart 5: 97–101 2010年9月13日閲覧。.

- ^ a b Tabern, DL; Volwiler, EH (October 1935). “Sulfur-containing barbiturate hypnotics”. Journal of the American Chemical Society 57 (10): 1961–3. doi:10.1021/ja01313a062.

- ^ Jackson, C (1913). “The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes”. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 17: 507–9. Reprinted in Jackson, Chevalier (May 1996). “The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes”. Pediatric Anesthesia 6 (3): 230. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.1996.tb00434.x.

- ^ Zeitels, S (March 1998). “Chevalier Jackson's contributions to direct laryngoscopy”. Journal of Voice 12 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(98)80069-6. PMID 9619973.

- ^ Jackson, C (1922). “I: Instrumentarium”. A manual of peroral endoscopy and laryngeal surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 17–52. ISBN 978-1-4326-6305-6 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Janeway, HH (November 1913). “Intra-tracheal anesthesia from the standpoint of the nose, throat and oral surgeon with a description of a new instrument for catheterizing the trachea”. The Laryngoscope 23 (11): 1082–90. doi:10.1288/00005537-191311000-00009.

- ^ Guedel, A; Waters, R (1928). “A new intratracheal catheter”. Anesthesia and Analgesia 7 (4): 238–239. doi:10.1213/00000539-192801000-00089.

- ^ Gale, J; Waters, R (1932). “Closed endobronchial anesthesia in thoracic surgery: preliminary report”. Anesthesia and Analgesia 11 (6): 283–288. doi:10.1213/00000539-193201000-00049.

- ^ Greenblatt, E; Butler, J; Venegas, J; Winkler, T (2014). “Pendelluft in the bronchial tree”. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology 117 (9): 979–988. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00466.2014. PMC 4217048. PMID 25170072.

- ^ Morris, L (1952). “A new vaporizer for liquid anesthetic agents”. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 13 (6): 587–593. doi:10.1097/00000542-195211000-00003. PMID 12986220.

- ^ Morris, L (2006). “Copper kettle revisited”. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 104 (4): 881–884. doi:10.1097/00000542-200604000-00034. PMID 16571985.

- ^ Eisleb, 0. & Schaumann, 0. (1939) Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 65, 967–968.

- ^ Scott C. C., Chen K. K. (1946). “The action of 1,1-diphenyl-1 (Dimethylaminoisopropyl) butanone-2, a potent analgesic agent”. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 87: 63–71. PMID 20986681.

- ^ Rowbotham, ES; Magill, I (1921). “Anæsthetics in the Plastic Surgery of the Face and Jaws”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 14 (Sect Anaesth): 17–27. doi:10.1177/003591572101401402. PMC 2152821. PMID 19981941.

- ^ Magill, I (14 July 1923). “The provision for expiration in endotracheal insufflations anaesthesia”. The Lancet 202 (5211): 68–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)37756-5.

- ^ Magill, I (December 1928). “Endotracheal Anæsthesia”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 22 (2): 85–8. PMC 2101959. PMID 19986772.

- ^ Magill, I (November 1930). “Technique in Endotracheal Anaesthesia”. British Medical Journal 2 (1243): 817–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1243.817-a. PMC 2451624. PMID 20775829.

- ^ Thomas, KB (July–August 1978). “Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill, KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA. A review of his publications and other references to his life and work”. Anaesthesia 33 (7): 628–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1978.tb08426.x. PMID 356665.

- ^ McLachlan, G (September 2008). “Sir Ivan Magill KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA, (1888–1986)”. Ulster Medical Journal 77 (3): 146–52. PMC 2604469. PMID 18956794.

- ^ a b Magill, I (October 1920). “Appliances and Preparations”. British Medical Journal 2 (3122): 670. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.571.670. PMC 2338485. PMID 20770050.

- ^ Magill, I (6 March 1926). “An improved laryngoscope for anaesthetists”. The Lancet 207 (5349): 500. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)17109-6.

- ^ Magill, I (30 April 1921). “A Portable Apparatus for Tracheal Insufflation Anaesthesia”. The Lancet 197 (5096): 918. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)55592-5.

- ^ Magill, I (11 June 1921). “Warming Ether Vapour for Inhalation”. The Lancet 197 (5102): 1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)24908-3.

- ^ Magill, I (4 August 1923). “An apparatus for the administration of nitrous oxide, oxygen, and ether”. The Lancet 202 (5214): 228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)22460-X.

- ^ Betcher, A (1977). “The civilizing of curare: a history of its development and introduction into anesthesiology”. Anesthesia & Analgesia 56 (2): 305–319. doi:10.1213/00000539-197703000-00032. PMID 322548.

- ^ Macintosh, RR (13 February 1943). “A new laryngoscope”. The Lancet 241 (6233): 205. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)89390-3.

- ^ Scott, J; Baker, PA (July 2009). “How did the Macintosh laryngoscope become so popular?”. Pediatric Anesthesia 19 (Suppl 1): 24–9. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03026.x. PMID 19572841.

- ^ Macintosh, RR (1 January 1949). “Marxist Genetics”. British Medical Journal 1 (4591): 26–28. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4591.26-b. PMC 2049235.

- ^ Venn, PH (March 1993). “The gum elastic bougie”. Anaesthesia 48 (3): 274–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06936.X.

- ^ Viswanathan, S; Campbell, C; Wood, DG; Riopelle, JM; Naraghi, M (November–December 1992). “The Eschmann Tracheal Tube Introducer. (Gum elastic bougie)”. Anesthesiology Review 19 (6): 29–34. PMID 10148170.

- ^ Henderson, JJ (January 2003). “Development of the 'gum-elastic bougie'”. Anaesthesia 58 (1): 103–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.296828.x. PMID 12492697.

- ^ Raventos, J; Goodall, R (1956). “The Action of Fluothane-A New Volatile Anaesthetic”. British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy 11 (4): 394–410. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1956.tb00007.x. PMC 1510559. PMID 13383118.

- ^ Trimmel, Helmut; Egger, Alexander; Doppler, Reinhard; Pimiskern, Mathias; Voelckel, Wolfgang G. (2022-01-15). “Usability and effectiveness of inhaled methoxyflurane for prehospital analgesia - a prospective, observational study”. BMC Emergency Medicine 22 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/s12873-021-00565-6. ISSN 1471-227X. PMC PMC8760876. PMID 35033003.

- ^ Mahboobi, N.; Esmaeili, S.; Safari, S.; Habibollahi, P.; Dabbagh, A.; Alavian, S. M. (2012-02). “Halothane: how should it be used in a developing country?”. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue De Sante De La Mediterranee Orientale = Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit 18 (2): 159–164. doi:10.26719/2012.18.2.159. ISSN 1020-3397. PMID 22571093.

- ^ Stanley, TH; Egan, TD; Van Aken, H (February 2008). “A Tribute to Dr. Paul A. J. Janssen: Entrepreneur Extraordinaire, Innovative Scientist, and Significant Contributor to Anesthesiology”. Anesthesia & Analgesia 106 (2): 451–62. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181605add. PMID 18227300.

- ^ Janssen, PA; Niemegeers, CJ; Schellekens, KH; Verbruggen, FJ; Van Nueten, JM (March 1963). “The pharmacology of dehydrobenzperidol, a new potent and short acting neuroleptic agent chemically related to Haloperidol”. Arzneimittel-Forschung 13: 205–11. PMID 13957425.

- ^ “Anesthésie sans barbituriques: la neuroleptanalgésie” (フランス語). Anesthésie, Analgésie, Réanimation 16: 1022–56. (1959). ISSN 0003-3014.

- ^ “Neurolept-analgesia: an alternative to general anesthesia”. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 5 (2): 73–84. (1961). doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1961.tb00085.x. ISSN 0001-5172. PMID 13729171.

- ^ Aubry, U; Carignan, G; Chare-Tee, D; Keeri-Szanto, M; Lavallee, JP (May 1966). “Neuroleptanalgesia with fentanyl-droperidol: An appreciation based on more than 1000 anaesthetics for major surgery”. Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal 13 (3): 263–71. doi:10.1007/BF03003549. PMID 5961929.

- ^ Corssen, G; Domino, EF; Sweet, RB (November–December 1964). “Neuroleptanalgesia and Anesthesia”. Anesthesia & Analgesia 43 (6): 748–63. doi:10.1213/00000539-196411000-00028. PMID 14230731.

- ^ “Neuroleptanalgesia and anesthesia: Experiences in 60 poor risk geriatric patients”. South Dakota Journal of Medicine 22 (9): 31–3. (September 1969). PMID 5259472.

- ^ J., PA; Eddy, NB (February 1960). “Compounds Related to Pethidine--IV. New General Chemical Methods of Increasing the Analgesic Activity of Pethidine”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1021/jm50008a003. PMID 14406754.

- ^ Janssen, PA; Niemegeers, CJ; Dony, JG (1963). “The inhibitory effect of fentanyl and other morphine-like analgesics on the warm water induced tail withdrawal reflex in rats”. Arzneimittel-Forschung 13: 502–7. PMID 13957426.

- ^ Niemegeers, CJ; Schellekens, KH; Van Bever, WF; Janssen, PA (1976). “Sufentanil, a very potent and extremely safe intravenous morphine-like compound in mice, rats and dogs”. Arzneimittel-Forschung 26 (8): 1551–6. PMID 12772.

- ^ “Alfentanil: a new narcotic induction agent”. Anesthesiology 53: S32. (1980). doi:10.1097/00000542-198009001-00032.

- ^ “Alfentanil (R39209)-a particularly short acting intravenous narcotic analgesic in rats”. Drug Development Research 1: 830–8. (1981). doi:10.1002/ddr.430010111. ISSN 0272-4391.

- ^ De Vos, V (22 July 1978). “Immobilisation of free-ranging wild animals using a new drug”. Veterinary Record 103 (4): 64–8. doi:10.1136/vr.103.4.64. PMID 685103.

- ^ Laduron, P; Janssen, PF (August 1982). “Axoplasmic transport and possible recycling of opiate receptors labelled with 3H-lofentanil”. Life Sciences 31 (5): 457–62. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(82)90331-9. PMID 6182434.

- ^ Morgan, M; Lumley, Jean; Whitwam, J.G. (26 April 1975). “Etomidate, a New Water-Soluble Non-barbiturate Intravenous Induction Agent”. The Lancet 305 (7913): 955–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92011-5. PMID 48126.

- ^ Murphy, P (July 1967). “A fibre-optic endoscope used for nasal intubation”. Anaesthesia 22 (3): 489–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1967.tb02771.x. PMID 4951601.

- ^ “[Cerebral function under etomidate, a new non-barbiturate i.v. hypnotic”] (ドイツ語). Der Anaesthesist 22 (8): 353–66. (August 1973). ISSN 0003-2417. PMID 4584133. オリジナルの20 July 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年9月27日閲覧。.

- ^ Wheeler M and Ovassapian A (2007). “Chapter 18: Fiberoptic endoscopy-aided technique”. In Benumof, JL. Benumof's Airway Management: Principles and Practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby-Elsevier. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-323-02233-0 2010年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ Agrò, F; Barzoi, G; Montecchia, F (May 2003). “Tracheal intubation using a Macintosh laryngoscope or a GlideScope in 15 patients with cervical spine immobilization”. British Journal of Anaesthesia 90 (5): 705–6. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg560. PMID 12697606.

- ^ Cooper, RM; Pacey, JA; Bishop, MJ; McCluskey, SA (February 2005). “Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in 728 patients”. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 52 (2): 191–8. doi:10.1007/BF03027728. PMID 15684262.

参考文献

- 松木明知『麻酔の歴史 150年の軌跡』克誠堂出版、1998年。ISBN 4-7719-0201-1。

- Maltby, J.Roger 著、菊地博達、岩瀬良範 訳『麻酔の偉人たち』総合医学社、2016年。ISBN 9784883786411。

関連文献

- Goldsmith, WM (1945). “Trepanation and the 'CatlinMark'”. American Antiquity 10 (4): 348–52. doi:10.2307/275576. JSTOR 275576.

- Guerra Doce, E (2006). “Evidencias del consumo de drogas en Europa durante la Prehistoria” (スペイン語). Trastornos Adictivos 8 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1016/S1575-0973(06)75106-6. オリジナルの15 May 2008時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年11月14日閲覧。.

- Gurlt, EJ「VI: Volkschirurgie in Japan in alter und neuerer」(ドイツ語)『Geschichte der Chirurgie und ihrer Ausübung』 1巻、Verlag von August Hirschwald、Berlin、1898年、83頁。2010年11月14日閲覧。

- Hrdlicka, A (1939). “Trepanation among prehistoric people, especially in America”. Ciba Foundation Symposium 1 (6): 170–7.

- Matsuki, A「A brief history of the biographical study of Seishu Hanaoka」『Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi』第51巻第3号、2005年、355–84頁、ISSN 0549-3323、PMID 16450478、2010年11月14日閲覧。

- Matsuki, A「Why did Hanaoka's Method of Anesthesia Decay Rapidly at the End of the Edo Period?」『Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi』第52巻第1号、2006年、40–1頁、ISSN 0549-3323。

- Ruffer, MA (1918). “Studies in paleopathology. Some recent researches on prehistoric trephining”. Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology 22: 90–104. doi:10.1002/path.1700220109.

- Stewart, TD (1958). “Stone Age skull surgery. A general review with emphasis on the New World”. Smithsonian Annual Report of the Board of Regents, 1957. pp. 469–91

- Arashiro Toshiaki, Ryukyu-Okinawa Rekishi Jinbutsuden, Okinawajijishuppan, 2006 p66 ISBN 978-4-903042-04-6

- "Reevaluation of surgical achievements by Tokumei Takamine". Matsuki A. Masui. November 2000; 49(11):1285-9. Japanese.[要文献特定詳細情報]

- "The secret anesthetic used in the repair of a hare-lip performed by Tokumei Takamine in Ryukyu". Matsuki A. Nippon Ishigaku Zasshi. October 1985 31(4):463-89. Japanese.

関連項目

- ヘンリー・E・G・ボイル(Henry Edmund Gaskin Boyle) - 初期の麻酔器を開発した麻酔科医

- ウォルター・チャニング(Walter Channing) - アメリカの産科麻酔科学の先駆者

- ジョセフ・トーマス・クローバー(Joseph Thomas Clover) - 19世紀イギリスの麻酔科医

外部リンク

- ウッド・ライブラリー-麻酔博物館(英語) - 麻酔科学における最も包括的な教育的、科学的なアーカイブのリソース。

- 「クロロホルム」分子レベルのライフセーバー - クロロホルムに関する興味深い事実を伝えるブリストル大学の記事。

- オーストラリア・ニュージーランド麻酔科医協会のモニター基準(英語、2002-01-25、アーカイブ)

- 英国王立麻酔科学会の患者向けサイト(英語、アーカイブ日付20051219)

- “華岡青洲が残した図譜の復元資料”. アメリカ国立医学図書館. 2010年7月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年7月28日閲覧。

- “麻酔の歴史” (ドイツ語). 2012年11月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年11月14日閲覧。

- “Anesthesia as a specialty - Past, present and future(邦訳: 専門科としての麻酔科 -過去・現在・未来)” (英語). Prof. Janusz Andres (Head of the Chair and Department). 2011年7月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年7月5日閲覧。