「動物」の版間の差分

タグ: モバイル編集 モバイルアプリ編集 Androidアプリ編集 |

en:Animal 19 July 2018, at 07:18よりコピー タグ: サイズの大幅な増減 ビジュアルエディター |

||

| 332行目: | 332行目: | ||

=== 各門の特徴とさらなる分類 === |

=== 各門の特徴とさらなる分類 === |

||

{{工事中|7月中|section=1}} |

{{工事中|7月中|section=1}} |

||

==== 前左右相称動物 ==== |

|||

== Phylogeny == |

|||

{{further|Lists of animals}}Animals are [[Monophyly|monophyletic]], meaning they are derived from a common ancestor and form a single [[clade]] within the [[Apoikozoa]]. The [[Choanoflagellata]] are their sister clade.<ref name="Budd2015">{{cite journal|last1=Budd|first1=Graham E|last2=Jensen|first2=Sören|year=2017|title=The origin of the animals and a 'Savannah' hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution|journal=Biological Reviews|volume=92|issue=1|pages=446–473|doi=10.1111/brv.12239|pmid=26588818}}</ref> The most [[Basal (phylogenetics)|basal]] animals, the [[Porifera]], [[Ctenophora]], Cnidaria, and Placozoa, have body plans that lack [[Symmetry in biology|bilateral symmetry]], but their relationships are still disputed. As of 2017, the Porifera are considered the basalmost animals.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Feuda|first=Roberto|last2=Dohrmann|first2=Martin|last3=Pett|first3=Walker|last4=Philippe|first4=Hervé|last5=Rota-Stabelli|first5=Omar|last6=Lartillot|first6=Nicolas|last7=Wörheide|first7=Gert|last8=Pisani|first8=Davide|year=2017|title=Improved Modeling of Compositional Heterogeneity Supports Sponges as Sister to All Other Animals|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982217314537|journal=Current Biology|volume=27|issue=24|pages=3864|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.008|pmid=29199080}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Pisani|first=Davide|last2=Pett|first2=Walker|last3=Dohrmann|first3=Martin|last4=Feuda|first4=Roberto|last5=Rota-Stabelli|first5=Omar|last6=Philippe|first6=Hervé|last7=Lartillot|first7=Nicolas|last8=Wörheide|first8=Gert|date=15 December 2015|title=Genomic data do not support comb jellies as the sister group to all other animals|url=http://www.pnas.org/content/112/50/15402|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=112|issue=50|pages=15402–15407|bibcode=2015PNAS..11215402P|doi=10.1073/pnas.1518127112|pmid=26621703|pmc=4687580}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Simion|first=Paul|last2=Philippe|first2=Hervé|last3=Baurain|first3=Denis|last4=Jager|first4=Muriel|last5=Richter|first5=Daniel J.|last6=Franco|first6=Arnaud Di|last7=Roure|first7=Béatrice|last8=Satoh|first8=Nori|last9=Quéinnec|first9=Éric|date=3 April 2017|title=A Large and Consistent Phylogenomic Dataset Supports Sponges as the Sister Group to All Other Animals|url=https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.031|journal=Current Biology|volume=27|issue=7|pages=958–967|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.031|pmid=28318975}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Giribet|first=Gonzalo|date=1 October 2016|title=Genomics and the animal tree of life: conflicts and future prospects|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/zsc.12215/abstract|journal=Zoologica Scripta|volume=45|pages=14–21|doi=10.1111/zsc.12215}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Laumer|first=Christopher E.|last2=Gruber-Vodicka|first2=Harald|last3=Hadfield|first3=Michael G.|last4=Pearse|first4=Vicki B.|last5=Riesgo|first5=Ana|last6=Marioni|first6=John C.|last7=Giribet|first7=Gonzalo|year=2017|title=Placozoans are eumetazoans related to Cnidaria|url=https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/10/11/200972|journal=BioRxiv|pages=200972|doi=10.1101/200972}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Eitel|first=Michael|last2=Francis|first2=Warren|last3=Osigus|first3=Hans-Jürgen|last4=Krebs|first4=Stefan|last5=Vargas|first5=Sergio|last6=Blum|first6=Helmut|last7=Williams|first7=Gray Argust|last8=Schierwater|first8=Bernd|last9=Wörheide|first9=Gert|date=2017-10-13|title=A taxogenomics approach uncovers a new genus in the phylum Placozoa|url=https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/10/13/202119|journal=BioRxiv|pages=202119|doi=10.1101/202119}}</ref> An alternative to the Porifera could be the Ctenophora,<ref>{{cite journal|last=Dunn|first=Casey W.|last2=Hejnol|first2=Andreas|last3=Matus|first3=David Q.|last4=Pang|first4=Kevin|last5=Browne|first5=William E.|last6=Smith|first6=Stephen A.|last7=Seaver|first7=Elaine|last8=Rouse|first8=Greg W.|last9=Obst|first9=Matthias|year=2008|title=Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life|url=http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nature06614|journal=Nature|volume=452|issue=7188|pages=745–749|bibcode=2008Natur.452..745D|doi=10.1038/nature06614|pmid=18322464}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Whelan|first=Nathan V.|last2=Kocot|first2=Kevin M.|last3=Moroz|first3=Tatiana P.|last4=Mukherjee|first4=Krishanu|last5=Williams|first5=Peter|last6=Paulay|first6=Gustav|last7=Moroz|first7=Leonid L.|last8=Halanych|first8=Kenneth M.|year=2017|title=Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals|url=http://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-017-0331-3|journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution|volume=1|issue=11|pages=1737|doi=10.1038/s41559-017-0331-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Shen|first=Xing-Xing|last2=Hittinger|first2=Chris Todd|last3=Rokas|first3=Antonis|date=2017-04-10|title=Contentious relationships in phylogenomic studies can be driven by a handful of genes|url=http://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-017-0126|journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution|volume=1|issue=5|pages=0126|doi=10.1038/s41559-017-0126}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Ryan|first=Joseph F.|last2=Pang|first2=Kevin|last3=Schnitzler|first3=Christine E.|last4=Nguyen|first4=Anh-Dao|last5=Moreland|first5=R. Travis|last6=Simmons|first6=David K.|last7=Koch|first7=Bernard J.|last8=Francis|first8=Warren R.|last9=Havlak|first9=Paul|date=13 December 2013|title=The Genome of the Ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and Its Implications for Cell Type Evolution|url=http://science.sciencemag.org/content/342/6164/1242592|journal=Science|volume=342|issue=6164|pages=1242592|doi=10.1126/science.1242592|pmid=24337300|pmc=3920664}}</ref> which like the Porifera lack [[Hox gene|hox genes]], [[Evolutionary developmental biology#Gene toolkit|important in body plan development]]. These genes are found in the Placozoa<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://emb.carnegiescience.edu/sites/emb.carnegiescience.edu/files/evodevo12.pdf|title=Evolution and Development|access-date=4 March 2018|date=1 May 2012|website=Carnegie Institution for Science Department of Embryology|page=38|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140302084415/http://emb.carnegiescience.edu/sites/emb.carnegiescience.edu/files/evodevo12.pdf|archive-date=2 March 2014|dead-url=yes}}</ref><ref name="Dellaporta2004">{{cite journal|last=Dellaporta|first=Stephen|last2=Holland|first2=Peter|last3=Schierwater|first3=Bernd|last4=Jakob|first4=Wolfgang|last5=Sagasser|first5=Sven|last6=Kuhn|first6=Kerstin|date=April 2004|title=The Trox-2 Hox/ParaHox gene of Trichoplax (Placozoa) marks an epithelial boundary|journal=Development Genes and Evolution|volume=214|issue=4|pages=170–175|doi=10.1007/s00427-004-0390-8}}</ref> and the higher animals, the Bilateria.<ref name="Peterson2001">{{cite journal|last1=Peterson|first1=Kevin J.|last2=Eernisse|first2=Douglas J|year=2001|title=Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: Inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x/full|journal=Evolution and Development|volume=3|issue=3|pages=170|accessdate=25 February 2018|doi=10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x|pmid=11440251}}</ref><ref name="KraemerEis2016">{{cite journal|last1=Kraemer-Eis|first1=Andrea|last2=Ferretti|first2=Luca|last3=Schiffer|first3=Philipp|last4=Heger|first4=Peter|last5=Wiehe|first5=Thomas|year=2016|title=A catalogue of Bilaterian-specific genes - their function and expression profiles in early development|url=https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2016/03/19/041806.full.pdf|accessdate=25 February 2018|doi=10.1101/041806}}</ref> 6,331 groups of [[Gene|genes]] common to all living animals have been identified; these may have arisen from a single [[Animal#Phylogeny|common ancestor]] that lived [[Cryogenian|650 million years ago]] in the [[Precambrian]]. 25 of these are novel core gene groups, found only in animals; of those, 8 are for essential components of the [[Wnt signaling pathway|Wnt]] and [[TGF-beta]] signalling pathways which may have enabled animals to become multicellular by providing a pattern for the body's system of axes (in three dimensions), and another 7 are for [[Transcription factor|transcription factors]] including [[homeodomain]] proteins involved in the [[Evo-devo gene toolkit|control of development]].<ref name="Zimmer2018">{{cite news|title=The Very First Animal Appeared Amid an Explosion of DNA|date=4 May 2018|last=Zimmer|first=Carl|authorlink=Carl Zimmer|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/04/science/first-animal-genes-evolution.html|accessdate=4 May 2018|work=[[The New York Times]]}}</ref><ref name="Paps2018">{{cite journal|last1=Paps|first1=Jordi|last2=Holland|first2=Peter W. H.|date=30 April 2018|title=Reconstruction of the ancestral metazoan genome reveals an increase in genomic novelty|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-04136-5|journal=[[Nature Communications]]|volume=9|number=1730 (2018)|accessdate=4 May 2018|bibcode=2018NatCo...9.1730P|doi=10.1038/s41467-018-04136-5}}</ref> |

|||

The [[phylogenetic tree]] (of major lineages only) indicates approximately how many millions of years ago ({{em|mya}}) the lineages split.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Peterson|first=Kevin J.|last2=Cotton|first2=James A.|last3=Gehling|first3=James G.|last4=Pisani|first4=Davide|date=27 April 2008|title=The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records|url=http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/363/1496/1435|journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences|volume=363|issue=1496|pages=1435–1443|doi=10.1098/rstb.2007.2233|pmid=18192191|pmc=2614224}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Parfrey|first=Laura Wegener|last2=Lahr|first2=Daniel J. G.|last3=Knoll|first3=Andrew H.|last4=Katz|first4=Laura A.|date=16 August 2011|title=Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks|url=http://www.pnas.org/content/108/33/13624|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=108|issue=33|pages=13624–13629|bibcode=2011PNAS..10813624P|doi=10.1073/pnas.1110633108|pmid=21810989|pmc=3158185}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://fossilcalibrations.org/|title=Raising the Standard in Fossil Calibration|accessdate=3 March 2018|website=Fossil Calibration Database}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Laumer|first=Christopher E.|last2=Gruber-Vodicka|first2=Harald|last3=Hadfield|first3=Michael G.|last4=Pearse|first4=Vicki B.|last5=Riesgo|first5=Ana|last6=Marioni|first6=John C.|last7=Giribet|first7=Gonzalo|date=2018-03-17|title=Placozoa and Cnidaria are sister taxa|url=https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/03/17/200972|journal=bioRxiv|pages=200972|language=en|doi=10.1101/200972}}</ref>{{Clade|{{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Choanoflagellate |Choanoflagellata]] [[File:Desmarella moniliformis.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|label2 ='''Animalia''' |sublabel2=760 mya |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Porifera]] [[File:Reef3859 - Flickr - NOAA Photo Library.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|label2=[[Eumetazoa]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Ctenophora]] [[File:Comb jelly.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|label2=[[ParaHoxozoa]] |

|||

|sublabel2=680 mya |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Placozoa]] [[File:Trichoplax adhaerens photograph.png|60 px]] |

|||

|2=[[Cnidaria]] [[File:Cauliflour Jellyfish, Cephea cephea at Marsa Shouna, Red Sea, Egypt SCUBA.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Bilateria]] |sublabel2=Triploblasts |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Xenacoelomorpha]] [[File:Proporus sp.png|60 px]] |

|||

|label2=[[Nephrozoa]] |sublabel2=650 mya |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|label1=[[Deuterostomia]] |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

<!--|sublabel1=525 mya --><!--Chordates--> |

|||

|1=[[Chordata]] [[File:Cyprinus carpio3.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|2=[[Echinodermata]] and allies [[File:Portugal 20140812-DSC01434 (21371237591).jpg|60 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2 =[[Protostomia]] |sublabel2=610 mya |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|label1=[[Ecdysozoa]] |sublabel1=>529 mya |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Arthropoda]] and allies [[File:Long nosed weevil edit.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|2=[[Nematoda]] and allies [[File:CelegansGoldsteinLabUNC.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Spiralia]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|label1=[[Gnathifera (clade)|Gnathifera]] |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Rotifera]] and allies [[File:Bdelloid Rotifer (cropped).jpg|50 px]] |

|||

|2=[[Chaetognatha]] [[File:Chaetoblack.png|60 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Platytrochozoa]] |sublabel2=580 mya |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Platyhelminthes]] and allies [[File:Sorocelis reticulosa.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|label2=[[Lophotrochozoa]] |sublabel2=550 mya |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Mollusca]] [[File:Grapevinesnail 01.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|2=[[Annelida]] and allies [[File:Polychaeta (no).JPG|75 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}}|style=font-size:80%; line-height:80%|label1=[[Apoikozoa]]|sublabel1=950 mya}} |

|||

{{anchor|Ctenophora.2C_Porifera.2C_Placozoa.2C_Cnidaria_and_Bilateria}} |

|||

=== Non-bilaterian animals === |

|||

[[ファイル:Elephant-ear-sponge.jpg|右|サムネイル|Non-bilaterians include sponges (centre) and corals (background).]] |

|||

Several animal phyla lack bilateral symmetry. Among these, the sponges (Porifera) probably diverged first, representing the oldest animal phylum.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Bhamrah|first1=H. S.|title=An Introduction to Porifera|year=2003|publisher=Anmol Publications|isbn=978-81-261-0675-2|page=58|last2=Juneja|first2=Kavita}}</ref> Sponges lack the complex organization found in most other animal phyla;<ref>{{cite book|last=Sumich|first=James L.|title=Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life|year=2008|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|isbn=978-0-7637-5730-4|page=67}}</ref> their cells are differentiated, but in most cases not organised into distinct tissues.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jessop|first=Nancy Meyer|title=Biosphere; a study of life|year=1970|publisher=Prentice-Hall|page=428}}</ref> They typically feed by drawing in water through pores.<ref>{{cite book|last=Sharma|first=N. S.|title=Continuity And Evolution Of Animals|year=2005|publisher=Mittal Publications|isbn=978-81-8293-018-6|page=106}}</ref> |

|||

The Ctenophora (comb jellies) and Cnidaria (which includes [[jellyfish]], [[Sea anemone|sea anemones]], and corals) are radially symmetric and have digestive chambers with a single opening, which serves as both mouth and anus.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Langstroth|first1=Lovell|editor-last=Newberry|editor-first=Todd|title=A Living Bay: The Underwater World of Monterey Bay|year=2000|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-22149-9|page=244|last2=Langstroth|first2=Libby}}</ref> Animals in both phyla have distinct tissues, but these are not organised into [[Organ (anatomy)|organs]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Safra|first=Jacob E.|title=The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 16|year=2003|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica|isbn=978-0-85229-961-6|page=523}}</ref> They are [[diploblastic]], having only two main germ layers, ectoderm and endoderm.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kotpal|first=R. L.|title=Modern Text Book of Zoology: Invertebrates|publisher=Rastogi Publications|isbn=978-81-7133-903-7|page=184}}</ref> The tiny [[Placozoan|placozoans]] are similar, but they do not have a permanent digestive chamber.<ref>{{cite book|author=Barnes, Robert D.|title=Invertebrate Zoology|year=1982|publisher=Holt-Saunders International|isbn=0-03-056747-5|pages=84–85}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/phyla/placozoa/placozoa.html|title=Introduction to Placozoa|accessdate=10 March 2018|author=<!--"A.G.C."-->|publisher=UCMP Berkeley}}</ref> |

|||

=== Bilaterian animals === |

|||

{{main|Bilateria|Symmetry (biology)#Bilateral symmetry}} |

|||

[[ファイル:Bilaterian_body_plan.svg|左|サムネイル|Idealised [[Bilateria|bilaterian]] body plan.{{efn|Compare [[:File:Annelid redone w white background.svg]] for a more specific and detailed model of a particular phylum with this general body plan.}} With an elongated body and a direction of movement the animal has head and tail ends. Sense organs and mouth form the [[Cephalisation|basis of the head]]. Opposed circular and longitudinal muscles enable [[Peristalsis|peristaltic motion]].]] |

|||

The remaining animals, the great majority – comprising some 29 phyla and over a million species – form a clade, the Bilateria. The body is [[Triploblasty|<!--this is the primary location for this wikilink-->triploblastic]], with three well-developed germ layers, and their tissues [[Organogenesis|form distinct organs]]. The digestive chamber has two openings, a mouth and an anus, and there is an internal body cavity, a [[coelom]] or pseudocoelom. Animals with this bilaterally symmetric [[body plan]] and a tendency to move in one direction have a head end (anterior) and a tail end (posterior) as well as a back (dorsal) and a belly (ventral); therefore they also have a left side and a right side.<ref name="Minelli2009" /><ref name="Brusca2016" /> |

|||

Having a front end means that this part of the body encounters stimuli, such as food, favouring [[cephalisation]], the development of a head with [[Sense organ|sense organs]] and a mouth. Many bilaterians have a combination of circular [[Muscle|muscles]] that constrict the body, making it longer, and an opposing set of longitudinal muscles, that shorten the body;<ref name="Brusca2016" /> these enable soft-bodied animals with a [[hydrostatic skeleton]] to move by [[peristalsis]].<ref name="Quillin">{{cite journal|author=Quillin, K. J.|date=May 1998|title=Ontogenetic scaling of hydrostatic skeletons: geometric, static stress and dynamic stress scaling of the earthworm lumbricus terrestris|url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9600869|journal=The Journal of Experimental Biology|volume=201|issue=12|pages=1871–83|pmid=9600869}}</ref> They also have a gut that extends through the basically cylindrical body from mouth to anus. Many bilaterian phyla have primary [[Larva|larvae]] which swim with [[cilia]] and have an apical organ containing sensory cells. However, there are exceptions to each of these characteristics; for example, adult echinoderms are radially symmetric (unlike their larvae), while some [[Helminths|parasitic worms]] have extremely simplified body structures.<ref name="Minelli2009">{{cite book|author=Minelli, Alessandro|title=Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jIASDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA53|year=2009|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-856620-5|page=53}}</ref><ref name="Brusca2016">{{Cite book|last=Brusca|first=Richard C.|title=Introduction to the Bilateria and the Phylum Xenacoelomorpha {{!}} Triploblasty and Bilateral Symmetry Provide New Avenues for Animal Radiation|url=http://www.sinauer.com/media/wysiwyg/samples/Brusca3e_Chapter_9.pdf|date=2016|publisher=Sinauer Associates|isbn=978-1605353753|pages=345–372|work=Invertebrates}}</ref> |

|||

Genetic studies have considerably changed zoologists' understanding of the relationships within the Bilateria. Most appear to belong to two major lineages, the [[protostomes]] and the [[deuterostomes]].<ref name="Telford 2008 pp. 457–459">{{cite journal|last=Telford|first=Maximilian J.|year=2008|title=Resolving Animal Phylogeny: A Sledgehammer for a Tough Nut?|journal=Developmental Cell|volume=14|issue=4|pages=457–459|doi=10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.016|pmid=18410719}}</ref> The basalmost bilaterians are the [[Xenacoelomorpha]].<ref name="Philippe2011">{{cite journal|last1=Philippe|first1=H.|last2=Brinkmann|first2=H.|last3=Copley|first3=R. R.|last4=Moroz|first4=L. L.|last5=Nakano|first5=H.|last6=Poustka|first6=A. J.|last7=Wallberg|first7=A.|last8=Peterson|first8=K. J.|last9=Telford|first9=M. J.|year=2011|title=Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to ''Xenoturbella''|journal=Nature|volume=470|issue=7333|pages=255–258|bibcode=2011Natur.470..255P|doi=10.1038/nature09676|pmid=21307940|pmc=4025995}}</ref><ref name="Perseke2007">{{cite journal|last1=Perseke|first1=M.|last2=Hankeln|first2=T.|last3=Weich|first3=B.|last4=Fritzsch|first4=G.|last5=Stadler|first5=P.F.|last6=Israelsson|first6=O.|last7=Bernhard|first7=D.|last8=Schlegel|first8=M.|date=August 2007|title=The mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: genomic architecture and phylogenetic analysis|url=http://www.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/Publications/PREPRINTS/07-009.pdf|journal=Theory Biosci|volume=126|issue=1|pages=35–42|doi=10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7|pmid=18087755}}</ref><ref name="Cannon 2016">{{cite journal|last=Cannon|first=Johanna T.|last2=Vellutini|first2=Bruno C.|last3=Smith III|first3=Julian.|last4=Ronquist|first4=Frederik|last5=Jondelius|first5=Ulf|last6=Hejnol|first6=Andreas|date=3 February 2016|title=Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa|url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v530/n7588/full/nature16520.html|journal=Nature|volume=530|issue=7588|pages=89–93|publisher=|bibcode=2016Natur.530...89C|doi=10.1038/nature16520|pmid=26842059|access-date=3 February 2016}}</ref>{{clear}} |

|||

==== Protostomes and deuterostomes ==== |

|||

{{main|Protostome|Deuterostome|}}{{further|Embryological origins of the mouth and anus}} |

|||

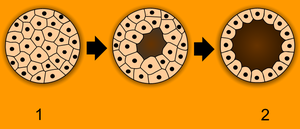

[[ファイル:Protovsdeuterostomes.svg|右|サムネイル|The bilaterian gut develops in two ways. In many [[Protostome|protostomes]], the blastopore develops into the mouth, while in [[Deuterostome|deuterostomes]] it becomes the anus.]] |

|||

Protostomes and deuterostomes differ in several ways. Early in development, deuterostome embryos undergo radial [[Cleavage (embryo)|cleavage]] during cell division, while many protostomes (the [[Spiralia]]) undergo spiral cleavage.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Valentine|first=James W.|date=July 1997|title=Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life|journal=PNAS|volume=94|issue=15|pages=8001–8005|publisher=The National Academy of Sciences|bibcode=1997PNAS...94.8001V|doi=10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001|pmid=9223303|pmc=21545}}</ref> Animals from both groups possess a complete digestive tract, but in protostomes the first opening of the [[Archenteron|embryonic gut]] develops into the mouth, and the anus forms secondarily. In deuterostomes, the anus forms first while the mouth develops secondarily.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Peters|first1=Kenneth E.|title=The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history|year=2005|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-83762-0|page=717|volume=2|last2=Walters|first2=Clifford C.|last3=Moldowan|first3=J. Michael}}</ref><ref name="Hejnol2009">{{cite book|last1=Hejnol|first1=A.|title=The mouth, the anus, and the blastopore – open questions about questionable openings|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230766195_The_mouth_the_anus_and_the_blastopore_-_open_questions_about_questionable_openings|date=2009|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0199570300|pages=33–40|last2=Martindale|first2=M.Q.|work=Animal Evolution — Genomes, Fossils, and Trees|veditors=Telford MJ, Littlewood DJ}}</ref> Most protostomes have [[Schizocoely|schizocoelous development]], where cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm. In deuterostomes, the mesoderm forms by [[Enterocoely|enterocoelic pouching]], through invagination of the endoderm.<ref>{{cite book|last=Safra|first=Jacob E.|title=The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3|year=2003|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica|isbn=978-0-85229-961-6|page=767}}</ref> |

|||

The main deuterostome phyla are the Echinodermata and the Chordata.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hyde|first=Kenneth|title=Zoology: An Inside View of Animals|year=2004|publisher=Kendall Hunt|isbn=978-0-7575-0997-1|page=345}}</ref> Echinoderms are exclusively marine and include [[starfish]], [[Sea urchin|sea urchins]], and [[Sea cucumber|sea cucumbers]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Alcamo|first=Edward|title=Biology Coloring Workbook|year=1998|publisher=The Princeton Review|isbn=978-0-679-77884-4|page=220}}</ref> The chordates are dominated by the [[vertebrates]] (animals with [[Vertebral column|backbones]]),<ref>{{cite book|last=Holmes|first=Thom|title=The First Vertebrates|year=2008|publisher=Infobase Publishing|isbn=978-0-8160-5958-4|p=64}}</ref> which consist of [[Fish|fishes]], [[Amphibia|amphibians]], [[Reptile|reptiles]], [[Bird|birds]], and [[Mammal|mammals]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Rice|first=Stanley A.|title=Encyclopedia of evolution|year=2007|publisher=Infobase Publishing|isbn=978-0-8160-5515-9|page=75}}</ref> The deuterostomes also include the [[Hemichordata]] (acorn worms).<ref>{{cite book|last1=Tobin|first1=Allan J.|title=Asking about life|year=2005|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-0-534-40653-0|page=497|last2=Dusheck|first2=Jennie}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Simakov|first=Oleg|last2=Kawashima|first2=Takeshi|last3=Marlétaz|first3=Ferdinand|last4=Jenkins|first4=Jerry|last5=Koyanagi|first5=Ryo|last6=Mitros|first6=Therese|last7=Hisata|first7=Kanako|last8=Bredeson|first8=Jessen|last9=Shoguchi|first9=Eiichi|date=26 November 2015|title=Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins|url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v527/n7579/full/nature16150.html|journal=Nature|volume=527|issue=7579|pages=459–465|bibcode=2015Natur.527..459S|doi=10.1038/nature16150|pmid=26580012|pmc=4729200}}</ref> |

|||

===== Ecdysozoa ===== |

|||

[[ファイル:Anax_Imperator_2(loz).JPG|サムネイル|[[Ecdysis]]: a [[dragonfly]] has emerged from its dry [[exuviae]] and is expanding its wings. Like other [[arthropods]], its body is [[Segmentation (biology)|divided into segments]].]] |

|||

{{main|Ecdysozoa}}The Ecdysozoa are protostomes, named after their shared [[Phenotypic trait|trait]] of [[ecdysis]], growth by moulting.<ref>{{cite book|last=Dawkins|first=Richard|authorlink=Richard Dawkins|title=The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution|year=2005|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt|isbn=978-0-618-61916-0|page=381}}</ref> They include the largest animal phylum, the Arthropoda, which contains insects, spiders, crabs, and their kin. All of these have a body divided into [[Segmentation (biology)|repeating segments]], typically with paired appendages. Two smaller phyla, the [[Onychophora]] and [[Tardigrada]], are close relatives of the arthropods and share these traits. The ecdysozoans also include the Nematoda or roundworms, perhaps the second largest animal phylum. Roundworms are typically microscopic, and occur in nearly every environment where there is water;<ref>{{cite book|last1=Prewitt|first1=Nancy L.|title=BioInquiry: making connections in biology|year=2003|publisher=John Wiley|isbn=978-0-471-20228-8|page=289|last2=Underwood|first2=Larry S.|last3=Surver|first3=William}}</ref> some are important parasites.<ref>{{cite book|last=Schmid-Hempel|first=Paul|title=Parasites in social insects|year=1998|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-05924-2|page=75}}</ref> Smaller phyla related to them are the [[Nematomorpha]] or horsehair worms, and the [[Kinorhyncha]], [[Priapulida]], and [[Loricifera]]. These groups have a reduced coelom, called a pseudocoelom.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Miller, Stephen A.|title=Zoology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BWZFAQAAIAAJ|year=2006|publisher=McGraw-Hill Higher Education|page=173|author2=Harley, John P.}}</ref> |

|||

===== Spiralia ===== |

|||

{{main|Spiralia}} |

|||

[[ファイル:Spiral_cleavage_in_Trochus.png|左|サムネイル|[[Spiral cleavage]] in a sea snail embryo]] |

|||

The Spiralia are a large group of protostomes that develop by spiral cleavage in the early embryo.<ref name="Shankland">{{cite journal|last1=Shankland|first1=M.|last2=Seaver|first2=E. C.|year=2000|title=Evolution of the bilaterian body plan: What have we learned from annelids?|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=97|issue=9|pages=4434–7|bibcode=2000PNAS...97.4434S|doi=10.1073/pnas.97.9.4434|jstor=122407|pmid=10781038|pmc=34316}}</ref> The Spiralia's phylogeny has been disputed, but it contains a large clade, the superphylum [[Lophotrochozoa]], and smaller groups of phyla such as the [[Rouphozoa]] which includes the [[Gastrotrich|gastrotrichs]] and the [[Flatworm|flatworms]]. All of these are grouped as the [[Platytrochozoa]], which has a sister group, the [[Gnathifera (clade)|Gnathifera]], which includes the [[Rotifer|rotifers]].<ref name="Struck2014">{{cite journal|last=Struck|first=Torsten H.|last2=Wey-Fabrizius|first2=Alexandra R.|last3=Golombek|first3=Anja|last4=Hering|first4=Lars|last5=Weigert|first5=Anne|last6=Bleidorn|first6=Christoph|last7=Klebow|first7=Sabrina|last8=Iakovenko|first8=Nataliia|last9=Hausdorf|first9=Bernhard|date=2014|title=Platyzoan Paraphyly Based on Phylogenomic Data Supports a Noncoelomate Ancestry of Spiralia|journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution|volume=31|issue=7|pages=1833–1849|doi=10.1093/molbev/msu143|pmid=24748651|last10=Petersen|first10=Malte|last11=Kück|first11=Patrick|last12=Herlyn|first12=Holger|last13=Hankeln|first13=Thomas}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fröbius|first=Andreas C.|last2=Funch|first2=Peter|date=April 2017|title=Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans|url=http://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-00020-w|journal=Nature Communications|volume=8|issue=1|bibcode=2017NatCo...8....9F|doi=10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w}}</ref> |

|||

The Lophotrochozoa includes the [[Mollusc|molluscs]], [[Annelid|annelids]], [[Brachiopod|brachiopods]], [[Nemertea|nemerteans]], [[bryozoa]] and [[Entoprocta|entoprocts]].<ref name="Struck2014" /><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hervé|first1=Philippe|last2=Lartillot|first2=Nicolas|last3=Brinkmann|first3=Henner|date=May 2005|title=Multigene Analyses of Bilaterian Animals Corroborate the Monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia|journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution|volume=22|issue=5|pages=1246–1253|doi=10.1093/molbev/msi111|pmid=15703236}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/phyla/lophotrochozoa.html|title=Introduction to the Lophotrochozoa {{!}} Of molluscs, worms, and lophophores...|accessdate=28 February 2018|publisher=UCMP Berkeley}}</ref> The molluscs, the second-largest animal phylum by number of described species, includes [[Snail|snails]], [[Clam|clams]], and [[Squid|squids]], while the annelids are the segmented worms, such as [[Earthworm|earthworms]], [[Lugworm|lugworms]], and [[Leech|leeches]]. These two groups have long been considered close relatives because they share [[trochophore]] larvae.<ref name="Giribet2000">{{cite journal|last1=Giribet|first1=G.|last2=Distel|first2=D.L.|last3=Polz|first3=M.|last4=Sterrer|first4=W.|last5=Wheeler|first5=W.C.|year=2000|title=Triploblastic relationships with emphasis on the acoelomates and the position of Gnathostomulida, Cycliophora, Plathelminthes, and Chaetognatha: a combined approach of 18S rDNA sequences and morphology|journal=Syst Biol|volume=49|issue=3|pages=539–562|doi=10.1080/10635159950127385|pmid=12116426}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Kim|first1=Chang Bae|last2=Moon|first2=Seung Yeo|last3=Gelder|first3=Stuart R.|last4=Kim|first4=Won|date=September 1996|title=Phylogenetic Relationships of Annelids, Molluscs, and Arthropods Evidenced from Molecules and Morphology|journal=Journal of Molecular Evolution|volume=43|issue=3|pages=207–215|doi=10.1007/PL00006079|pmid=8703086}}</ref> |

|||

== History of classification == |

|||

{{further|Taxonomy (biology)|History of zoology (through 1859)|History of zoology since 1859}} |

|||

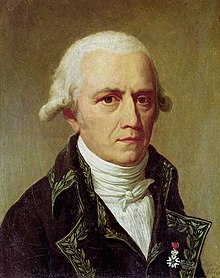

[[ファイル:Jean-Baptiste_de_Lamarck.jpg|左|サムネイル|[[Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck]] led the creation of a modern classification of invertebrates, breaking up Linnaeus's "Vermes" into 9 phyla by 1809.<ref name="Gould2011" />]] |

|||

In the [[classical era]], Aristotle [[Aristotle's biology|divided animals]],{{efn|In his ''[[History of Animals]]'' and ''[[Parts of Animals]]''.}} based on his own observations, into those with blood (roughly, the vertebrates) and those without. The animals were then [[Scala naturae|arranged on a scale]] from man (with blood, 2 legs, rational soul) down through the live-bearing tetrapods (with blood, 4 legs, sensitive soul) and other groups such as crustaceans (no blood, many legs, sensitive soul) down to spontaneously-generating creatures like sponges (no blood, no legs, vegetable soul). [[Aristotle]] was uncertain whether sponges were animals, which in his system ought to have sensation, appetite, and locomotion, or plants, which did not: he knew that sponges could sense touch, and would contract if about to be pulled off their rocks, but that they were rooted like plants and never moved about.<ref>{{cite book|last=Leroi|first=Armand Marie|authorlink=Armand Marie Leroi|title=The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science|date=2014|publisher=Bloomsbury|isbn=978-1-4088-3622-4|pages=111–119, 270–271|titlelink=Aristotle's Lagoon}}</ref> |

|||

In 1758, [[Carl Linnaeus]] created the first hierarchical classification in his ''[[Systema Naturae]]''.<ref name="Linn1758">{{cite book|last=Linnaeus|first=Carl|authorlink=Carl Linnaeus|title=Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.|url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/542|edition=[[10th edition of Systema Naturae |10th]]|year=1758|accessdate=22 September 2008|publisher=Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii)|language=Latin|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081010032456/http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/542|deadurl=no|archivedate=10 October 2008}}</ref> In his original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of [[Vermes in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae|Vermes]], [[Insecta in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae|Insecta]], [[Pisces in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae|Pisces]], [[Amphibia in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae|Amphibia]], [[Aves in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae|Aves]], and [[Mammalia in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae|Mammalia]]. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the [[Chordate|Chordata]], while his Insecta (which included the crustaceans and arachnids) and Vermes have been renamed or broken up. The process was begun in 1793 by [[Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck]], who called the Vermes ''une espèce de chaos'' (a sort of chaos){{efn|The prefix ''une espèce de'' is pejorative.<ref>{{cite web |title=Espèce de |url=http://dictionnaire.reverso.net/francais-anglais/esp%C3%A8ce%20de%20cr%C3%A9tin |publisher=Reverso Dictionnnaire |accessdate=1 March 2018}}</ref>}} and split the group into three new phyla, worms, echinoderms, and polyps (which contained corals and jellyfish). By 1809, in his ''[[Philosophie Zoologique]]'', Lamarck had created 9 phyla apart from vertebrates (where he still had 4 phyla: mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish) and molluscs, namely [[Cirripede|cirripedes]], annelids, crustaceans, arachnids, insects, worms, [[Radiata|radiates]], polyps, and [[Infusoria|infusorians]].<ref name="Gould2011">{{cite book|last=Gould|first=Stephen Jay|authorlink=Stephen Jay Gould|title=The Lying Stones of Marrakech|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wApMpVmi-5gC&pg=PA130|year=2011|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-06167-5|pages=130–134}}</ref> |

|||

In his 1817 ''[[Le Règne Animal]]'', [[Georges Cuvier]] used [[comparative anatomy]] to group the animals into four ''embranchements'' ("branches" with different body plans, roughly corresponding to phyla), namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals (arthropods and annelids), and zoophytes (echinoderms, cnidaria and other forms).<ref>{{cite book|author=De Wit, Hendrik C. D.|title=Histoire du Développement de la Biologie, Volume III|date=1994|publisher=Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes|isbn=2-88074-264-1|pages=94–96}}</ref> This division into four was followed by the embryologist [[Karl Ernst von Baer]] in 1828, the zoologist [[Louis Agassiz]] in 1857, and the comparative anatomist [[Richard Owen]] in 1860.<ref name="Valentine2004" /> |

|||

In 1874, [[Ernst Haeckel]] divided the animal kingdom into two subkingdoms: Metazoa (multicellular animals, with five phyla: coelenterates, echinoderms, articulates, molluscs, and vertebrates) and Protozoa (single-celled animals), including a sixth animal phylum, sponges.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Haeckel|first1=Ernst|authorlink=Ernst Haeckel|title=Anthropogenie oder Entwickelungsgeschichte des menschen|year=1874|language=German|page=202}}</ref><ref name="Valentine2004">{{cite book|last=Valentine|first=James W.|title=On the Origin of Phyla|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DMBkmHm5fe4C&pg=PA8|year=2004|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-84548-7|pages=7–8}}</ref> The protozoa were later moved to the former kingdom [[Protista]], leaving only the Metazoa as a synonym of Animalia.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hutchins|first1=Michael|title=Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia|edition=2nd|year=2003|publisher=Gale|isbn=0-7876-5777-8|page=3}}</ref> |

|||

== In human culture == |

|||

[[ファイル:Carni_bovine_macellate.JPG|サムネイル|Sides of [[beef]] in a [[slaughterhouse]]]] |

|||

{{main|Animals in culture}}The human population exploits a large number of other animal species for food, both of [[Domestication of animals|domesticated]] [[livestock]] species in [[animal husbandry]] and, mainly at sea, by hunting wild species.<ref name="FAOFish">{{cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/fishery/|title=Fisheries and Aquaculture|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=FAO}}</ref><ref name="Economist" /> Marine fish of many species are [[Fishing|caught commercially]] for food. A smaller number of species are [[Fish farming|farmed commercially]].<ref name="FAOFish" /><ref>{{cite book|last1=Helfman|first1=Gene S.|title=Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources|date=2007|publisher=Island Press|isbn=1-59726-760-0|page=11}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/i2727e/i2727e01.pdf|title=World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture|accessdate=13 August 2015|website=fao.org|publisher=FAO}}</ref> Invertebrates including [[Cephalopod|cephalopods]], [[Crustacea|crustaceans]], and [[bivalve]] or [[gastropod]] molluscs are hunted or farmed for food.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-85675992.html|title=Shellfish climbs up the popularity ladder|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=HighBeam Research}}</ref> Chickens, cattle, sheep, pigs and other animals are raised as livestock for meat across the world.<ref name="Economist">{{cite web|url=https://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/07/global-livestock-counts|title=Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens|accessdate=23 June 2016|date=27 July 2011|publisher=[[The Economist]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://cattle-today.com/|title=Breeds of Cattle at CATTLE TODAY|accessdate=15 October 2013|author=Cattle Today|publisher=Cattle-today.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/U4900T/u4900T0m.htm|title=Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems|accessdate=23 June 2016|publisher=[[Food and Agriculture Organization]]|last1=Lukefahr|first1=S.D.|last2=Cheeke|first2=P.R.}}</ref> Animal fibres such as wool are used to make textiles, while animal [[Sinew|sinews]] have been used as lashings and bindings, and leather is widely used to make shoes and other items. Animals have been hunted and farmed for their fur to make items such as coats and hats.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.peta.org/issues/animals-used-for-clothing/|title=Animals Used for Clothing|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=PETA}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.naturalfibres2009.org/en/fibres/|title=Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=Natural Fibres}}</ref> Dyestuffs including [[carmine]] ([[cochineal]]),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/v8879e/v8879e09.htm|title=Cochineal and Carmine|accessdate=June 16, 2015|work=Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems|publisher=FAO}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/ColorAdditives/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm153038.htm|title=Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine|accessdate=6 July 2016|publisher=FDA}}</ref> [[shellac]],<ref>{{cite news|title=How Shellac Is Manufactured|date=18 Dec 1937|url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55073762|accessdate=17 July 2015|publisher=The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 – 1954)}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|year=2003|title=Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets|journal=Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy|volume=29|issue=8|pages=925–938|doi=10.1081/ddc-120024188|pmid=14570313|author1=Pearnchob, N.|author2=Siepmann, J.|author3=Bodmeier, R.}}</ref> and [[Kermes (dye)|kermes]]<ref>{{cite book|last=Barber|first=E. J. W.|title=Prehistoric Textiles|year=1991|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=0-691-00224-X|pages=230–231}}</ref><ref name="Munro214">{{cite book|author=Munro, John H.|editor=Jenkins, David|title=Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology, and Organisation|year=2003|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=0-521-34107-8|pages=214–215|work=The Cambridge History of Western Textiles}}</ref> have been made from the bodies of insects. [[Working animals]] including cattle and horses have been used for work and transport from the first days of agriculture.<ref name="Pond2004">{{cite book|last=Pond|first=Wilson G.|title=Encyclopedia of Animal Science|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1SQl7Ao3mHoC&pg=PA248|year=2004|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-0-8247-5496-9|pages=248–250}}</ref> |

|||

Animals such as the fruit fly ''[[Drosophila melanogaster]]'' serve a major role in science as [[Model organism|experimental models]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aht.org.uk/cms-display/genetics.html|title=Genetics Research|accessdate=24 June 2016|publisher=Animal Health Trust}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.animalresearch.info/en/drug-development/|title=Drug Development|accessdate=24 June 2016|publisher=Animal Research.info}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/animals/using/experiments_1.shtml|title=Animal Experimentation|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=BBC}}</ref><ref name="EUstatistics2013">{{cite web|url=http://speakingofresearch.com/2013/12/12/eu-statistics-show-decline-in-animal-research-numbers/|title=EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers|accessdate=January 24, 2016|year=2013|publisher=Speaking of Research}}</ref> Animals have been used to create [[Vaccine|vaccines]] since their discovery in the 18th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.actip.org/library/vaccines-and-animal-cell-technology/|title=Vaccines and animal cell technology|accessdate=9 July 2016|publisher=Animal Cell Technology Industrial Platform}}</ref> Some medicines such as the cancer drug [[Yondelis]] are based on [[Toxin|toxins]] or other molecules of animal origin.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://publications.nigms.nih.gov/medbydesign/chapter3.html|title=Medicines by Design|accessdate=9 July 2016|publisher=National Institute of Health}}</ref> |

|||

[[ファイル:Hebbuz.JPG|左|サムネイル|A [[gun dog]] retrieving a duck during a hunt]] |

|||

People have used [[Hunting dog|hunting dogs]] to help chase down and retrieve animals,<ref>{{cite book|author=Fergus, Charles|title=Gun Dog Breeds, A Guide to Spaniels, Retrievers, and Pointing Dogs|date=2002|publisher=The Lyons Press|isbn=1-58574-618-5}}</ref> and [[Bird of prey|birds of prey]] to catch birds and mammals,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thefalconrycentre.co.uk/bird-info/conservation/nocturnal-raptors/history-falconry/|title=History of Falconry|accessdate=22 April 2016|publisher=The Falconry Centre}}</ref> while tethered [[Cormorant|cormorants]] have been [[Cormorant fishing|used to catch fish]].<ref name="King2013">{{cite book|author=King, Richard J.|title=The Devil's Cormorant: A Natural History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ucGyAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA9|date=2013|publisher=University of New Hampshire Press|isbn=978-1-61168-225-0|page=9}}</ref> [[Poison dart frog|Poison dart frogs]] have been used to poison the tips of [[Blowdart|blowpipe darts]].<ref name="amphibiaweb1">{{cite web|url=http://amphibiaweb.org/lists/Dendrobatidae.shtml|title=AmphibiaWeb – Dendrobatidae|accessdate=2008-10-10|publisher=AmphibiaWeb}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Dendrobatidae.html|title=Dendrobatidae|accessdate=9 July 2016|author=Heying, H.|year=2003|publisher=Animal Diversity Web}}</ref> A wide variety of animals are kept as pets, from invertebrates such as tarantulas and octopuses, insects including [[Praying mantis|praying mantises]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.keepinginsects.com/cockroaches-locusts-ants/|title=Other bugs|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=Keeping Insects}}</ref> reptiles such as [[Snake|snakes]] and [[Chameleon|chameleons]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.anapsid.org/parent.html|title=So, you think you want a reptile?|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=Anapsid.org|last1=Kaplan|first1=Melissa}}</ref> and birds including [[Canary (bird)|canaries]], [[Parakeet|parakeets]] and [[Parrot|parrots]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.humanesociety.org/animals/pet_birds/|title=Pet Birds|accessdate=8 July 2016|publisher=PDSA}}</ref> all finding a place. However, the most kept pet species are mammals, namely [[Dog|dogs]], [[Cat|cats]], and [[Rabbit|rabbits]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.shea-online.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Animals%20in%20Healthcare%20Facilities.pdf|title=Animals in Healthcare Facilities|year=2012|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304102728/http://www.shea-online.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Animals%20in%20Healthcare%20Facilities.pdf|archivedate=4 March 2016|deadurl=yes}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.humanesociety.org/issues/pet_overpopulation/facts/pet_ownership_statistics.html|title=U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics|accessdate=27 April 2012|last=The Humane Society of the United States}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/emergingissues/downloads/RabbitReport1.pdf|title=U.S. Rabbit Industry profile|accessdate=10 July 2013|last=USDA|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131020161216/http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/emergingissues/downloads/RabbitReport1.pdf|archivedate=20 October 2013|deadurl=yes|df=}}</ref> There is a tension between the role of animals as companions to humans, and their existence as [[Animal rights|individuals with rights]] of their own.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Plous, S.|date=1993|title=The Role of Animals in Human Society|journal=Journal of Social Issues|volume=49|issue=1|pages=1–9|doi=10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00906.x}}</ref> A wide variety of terrestrial and aquatic animals are hunted [[Animals in sport|for sport]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hummel|first1=Richard|title=Hunting and Fishing for Sport: Commerce, Controversy, Popular Culture|date=1994|publisher=Popular Press|isbn=978-0-87972-646-1}}</ref> |

|||

[[ファイル:Alexander_Coosemans_-_Still_Life_with_Lobster_and_Oysters.jpg|サムネイル|Artistic vision: ''[[Still Life]] with [[Lobster]] and [[Oyster|Oysters]]'' by [[Alexander Coosemans]], c. 1660]] |

|||

Animals have been the [[Animal style|subjects of art]] from the earliest times, both historical, as in [[Ancient Egypt]], and prehistoric, as in the [[Lascaux|cave paintings at Lascaux]]. Major animal paintings include [[Albrecht Dürer]]'s 1515 ''[[Dürer's Rhinoceros|The Rhinoceros]]'', and [[George Stubbs]]'s c. 1762 horse portrait ''[[Whistlejacket]]''.<ref name="Jones">{{cite news|title=The top 10 animal portraits in art|date=27 June 2014|last1=Jones|first1=Jonathan|url=https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/jun/27/top-10-animal-portraits-in-art|accessdate=24 June 2016|agency=[[The Guardian]]}}</ref> [[Arthropods in film|Insects]], birds and mammals play roles in literature and film,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199791286/obo-9780199791286-0044.xml|title=Animals in Film and Media|accessdate=24 June 2016|date=29 October 2013|publisher=Oxford Bibliographies|doi=10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0044|last1=Paterson|first1=Jennifer}}</ref> such as in giant bug movies.<ref name="GregersdotterHöglund2016">{{cite book|last1=Gregersdotter|first1=Katarina|title=Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hV-hCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA147|date=2016|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-1-137-49639-3|page=147|last2=Höglund|first2=Johan|last3=Hållén|first3=Nicklas}}</ref><ref name="WarrenThomas2009">{{cite book|last1=Warren|first1=Bill|title=Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B7kUCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT32|date=2009|publisher=McFarland|isbn=978-1-4766-2505-8|page=32|last2=Thomas|first2=Bill}}</ref><ref name="Crouse2008">{{cite book|last=Crouse|first=Richard|title=Son of the 100 Best Movies You've Never Seen|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B5alnowvF3sC&pg=PT200|year=2008|publisher=ECW Press|isbn=978-1-55490-330-6|page=200}}</ref> Animals including [[Insects in mythology|insects]]<ref name="Hearn" /> and mammals<ref name="TFL" /> feature in mythology and religion. In both Japan and Europe, a [[butterfly]] was seen as the personification of a person's soul,<ref name="Hearn">{{cite book|last=Hearn|first=Lafcadio|authorlink=Lafcadio Hearn|title=Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things|year=1904|publisher=Dover|isbn=0-486-21901-1|titlelink=Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=did;cc=did;rgn=main;view=text;idno=did2222.0001.694|title=Butterfly|accessdate=10 July 2016|work=Encyclopedia of Diderot and D'Alembert}}</ref><ref>Hutchins, M., Arthur V. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Volume 3, Insects. Gale, 2003.</ref> while the [[Scarab (artifact)|scarab beetle]] was sacred in ancient Egypt.<ref>{{cite book|author=Ben-Tor, Daphna|title=Scarabs, A Reflection of Ancient Egypt|date=1989|publisher=|isbn=965-278-083-9|page=8|location=Jerusalem}}</ref> Among the mammals, [[Cattle in religion and mythology|cattle]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-34513185|title=Why the humble cow is India's most polarising animal|accessdate=9 July 2016|publisher=BBC|last1=Biswas|first1=Soutik}}</ref> [[Deer in mythology|deer]],<ref name="TFL">{{cite web|url=http://treesforlife.org.uk/forest/mythology-folklore/deer/|title=Deer|accessdate=23 June 2016|publisher=[[Trees for Life (Scotland) |Trees for Life]]}}</ref> [[Horse worship|horses]],<ref>{{cite book|author=Robert Hans van Gulik|title=Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan|publisher=Brill Archive|page=9}}</ref> [[Cultural depictions of lions|lions]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://lionalert.org/page/Lion_Depiction_Across_Ancient_and_Modern_Religions|title=Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions|accessdate=6 July 2016|date=24 June 2012|publisher=ALERT|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160923134807/https://lionalert.org/page/Lion_Depiction_Across_Ancient_and_Modern_Religions|archivedate=23 September 2016|last1=Grainger|first1=Richard|deadurl=yes}}</ref> [[Bat#Cultural significance|bats]]<ref name="ReadGonzalez">{{cite book|last1=Read|first1=Kay Almere|title=Mesoamerican Mythology|year=2000|publisher=Oxford University Press|pages=132–134|last2=Gonzalez|first2=Jason J.}}</ref> and [[Wolves in folklore, religion and mythology|wolves]]<ref>{{cite book|author=McCone, Kim R.|editor=Meid, W.|title=Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen|date=1987|publisher=|pages=101–154|location=Innsbruck|work=Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz}}</ref> are the subjects of myths and worship. The [[Signs of the zodiac|signs of the Western]] and [[Chinese zodiac|Chinese zodiacs]] are based on animals.<ref>Lau, Theodora, ''The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes'', pp. 2–8, 30–5, 60–4, 88–94, 118–24, 148–53, 178–84, 208–13, 238–44, 270–78, 306–12, 338–44, Souvenir Press, New York, 2005</ref><ref name="Tester1987">{{cite book|last=Tester|first=S. Jim|title=A History of Western Astrology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L0HSvH96alIC&pg=PA31|year=1987|publisher=Boydell & Brewer|isbn=978-0-85115-446-6|pages=31–33 and passim}}</ref> |

|||

=== 前左右相称動物 === |

|||

前左右相称動物<ref name="Fujita10-113" group="注釈" />に属する4つの門の間の関係、およびこれら4つの門と左右相称動物との関係は2010年現在、分子系統解析でも定まっていない<ref>[[#藤田10|藤田10]], p.114.</ref>。 |

前左右相称動物<ref name="Fujita10-113" group="注釈" />に属する4つの門の間の関係、およびこれら4つの門と左右相称動物との関係は2010年現在、分子系統解析でも定まっていない<ref>[[#藤田10|藤田10]], p.114.</ref>。 |

||

2018年7月19日 (木) 09:08時点における版

| 動物界 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

各画像説明[注釈 1]

| ||||||

| 分類 | ||||||

| ||||||

| 門 | ||||||

|

本文参照 |

動物(どうぶつ、羅: Animalia、単数: Animal)とは、

- 生物学において、動物とは生物の分類群の一つで、一般に運動能力と感覚を持つ多細胞生物である。「動物」という言葉がつく分類群名としては後生動物や原生動物がある。後者は進化的に異なる雑多な生物をまとめたグループ(多系統群)とされているが、いずれも後生動物とは別系統である。本稿でいう「動物」は後生動物の方を指す。

- 日常語において、動物とは1.の意味の動物のうち、ヒト以外のもの[1]。特に哺乳類に属する生物を指す事が多い[1]。

本項では1の意味を解説する。

概要

動物は、哺乳類、爬虫類、鳥類、両生類、魚類といった脊椎動物はもちろん、貝類、昆虫、サナダムシ、カイメンなど、幅広い種類の生物を含んだ分類群である。

20世紀末の分子遺伝学の知見を踏まえると、生物は真正細菌、古細菌、真核生物の3つに分かれるが(3ドメイン説)[2][3][4]、動物はそのうちの真核生物に属し、他に真核生物に属するものとしては植物、菌類(キノコやカビ)、原生生物が挙げられる。なお、原生生物の一部である原生動物(ゾウリムシ、ミドリムシ、アメーバ等)は本稿で言う動物(後生動物)とは別系統であり、しかも多系統である事が判明している。

なお、初等教育では3ドメイン説以前の二界説(2011年まで)ないし五界説(2012年以降)に基づいて生物の分類を説明している[5]。二界説に基づいた説明では原生動物を「動物」とみなしていたが、すでに述べたように3ドメイン説では(後生)動物とは別系統であるとみなされている。一方、五界説での動物は3ドメイン説のものと基本的に同じであり、原生動物は原生生物として動物とは区別されている。

動物は真核生物の中ではオピストコンタ(後方鞭毛生物)という単系統性が強く支持されている分類に属し、ここには動物以外に菌類や一部の真核生物が属する。オピストコンタに属する生物は、後ろ側にある1本の鞭毛で進むという共有形質を持ち、動物の精子やツボカビの胞子が持つ鞭毛がこれにあたる。

さらにオピストコンタにはホロゾアという分類と、Holomycotaという分類があり、動物は前者、菌類は後者に属する。

特徴

- 多細胞の真核生物である[6][7]

- 従属栄養生物である[7][8]

- 非常に少数の例外的な動物を除き、好気呼吸する[9]

- 運動性がある[10](すなわち、自発的に体を動かす事ができる)。ただし生涯の途中で付着生物と化す動物もいる

- ほとんどの動物には、胚発生の初期に胞胚という段階がある[11]。

動物の細胞

動物の細胞は、全ての生物の細胞に共通した以下の構造を持つ。

- 細胞膜:細胞を包んでいる膜[12]。内部は生体物質を含む水溶液があり代謝の場となっている。リボソーム、細胞質(原形質)といった共通の構成要素を持っている。

- DNA:塩基配列または遺伝暗号 (genetic code)と言うヌクレオチドの塩基部分が並ぶ構造を持ち[13]、遺伝情報の継承と発現を担う。真核細胞のDNA は、一本または複数本の分子から構成される直線状で原核生物よりも多く[14]、染色体と呼ばれる[15]。

- 細胞質:細胞の細胞膜で囲まれた部分である原形質のうち、細胞核以外の領域のこと。真核細胞の細胞質には細胞骨格(サイトスケルトン)と呼ばれる微小な管やフィラメント状がつくる網目もしくは束状をした3次元構造[16]がある。これが特に発達した動物の細胞では、細胞骨格が各細胞の形を決定づける。

細胞小器官

典型的な動物細胞には、以下のような細胞小器官がある(番号は図のものと対応):

- 核小体(仁):細胞核の中に存在する、分子密度の高い領域で、rRNAの転写やリボソームの構築が行われる。

- 細胞核:細胞の遺伝情報の保存と伝達を行う。

- リボソーム:mRNAの遺伝情報を読み取ってタンパク質へと変換する機構である翻訳が行われる。

- 小胞:細胞内にある膜に包まれた袋状の構造で、細胞中に物質を貯蔵したり、細胞内外に物質を輸送するために用いられる。代表的なものに、液胞やリソソームがある。

- 粗面小胞体:リボソームが付着している小胞体の総称。

- ゴルジ体:へん平な袋状の膜構造が重なっており、細胞外へ分泌されるタンパク質の糖鎖修飾や、リボソームを構成するタンパク質のプロセシングに機能する。

- 微小管:細胞中に見いだされる直径約 25 nm の管状の構造であり、主にチューブリンと呼ばれるタンパク質からなる。細胞骨格の一種。細胞分裂の際に形成される分裂装置(星状体・紡錘体・染色体をまとめてこう呼ぶ)の主体。

- 滑面小胞体:リボソームが付着していない小胞体の総称。通常細管上の網目構造をとる。粗面小胞体とゴルジ複合体シス網との移行領域、粗面小胞体との連続部位に存在する。トリグリセリド、コレステロール、ステロイドホルモンなど脂質成分の合成やCa2+の貯蔵などを行う。

- ミトコンドリア:二重の生体膜からなり、独自のDNA(ミトコンドリアDNA=mtDNA)を持ち、分裂、増殖する。mtDNAはATP合成以外の生命現象にも関与する。酸素呼吸(好気呼吸)の場として知られている。また、細胞のアポトーシスにおいても重要な役割を担っている。mtDNAとその遺伝子産物は一部が細胞表面にも局在し突然変異は自然免疫系が特異的に排除[17] する。ミトコンドリアは好気性細菌でリケッチアに近いαプロテオバクテリアが真核細胞に共生することによって獲得されたと考えられている[18]。

- 液胞:電子顕微鏡で観察したときのみ、動物細胞内にもみられる。主な役割として、ブドウ糖のような代謝産物の貯蔵、無機塩類のようなイオンを用いた浸透圧の調節・リゾチームを初めとした分解酵素が入っており不用物の細胞内消化、不用物の貯蔵がある。

- 細胞質基質:細胞質から細胞内小器官を除いた部分のこと。真核生物では細胞質基質はどちらかと言えば細胞の基礎的な代謝機能の場となっている。

- リソソーム:生体膜につつまれた構造体で細胞内消化の場。

- 中心体:細胞分裂の際、中心的な役割を果たす。

細胞外マトリックス

動物の細胞はコラーゲンと伸縮性のある糖タンパク質からなる特徴的な細胞外マトリックスで囲まれている[19]。細胞外マトリックスは細胞外の空間を充填する物質であると同時に、骨格的役割(石灰化による骨、貝殻、海綿骨針といった組織の形成[20] )、細胞接着における足場の役割(例:基底膜やフィブロネクチン)、細胞増殖因子などの保持・提供する役割(例:ヘパラン硫酸に結合する細胞増殖因子FGF)などを担う。また動物細胞は、密着結合、ギャップ結合、接着斑などにより細胞結合・細胞接着している[21]。

海綿動物や平板動物のような少数の例外を除き、動物の体は組織に分化しており[22]、組織としては例えば筋肉や神経がある。

生殖、発生、分化

生殖

ほぼ全ての動物は何らかの形で有性生殖を行い[23]、その際減数分裂により一倍体の配偶子を作る。2つの配偶子が融合する事で新しい個体が生まれるが、この場合小さくて運動性がある配偶子を精子、大きくて運動性を持たない配偶子を卵子といい[24]、配偶子が融合する過程を受精、受精の結果できあがった細胞を受精卵という[25]。また精子を作る個体をオス、卵子を作る個体をメスという。一つの個体が精子と卵子を両方作れる場合は雌雄同体であるという。

発生

一倍体である精子と卵子が受精する事で、二倍体の受精卵が形成される。この際精子由来のミトコンドリアは酵素により分解されるので[26]、ミトコンドリアは卵子からしか受精卵に伝わらない。

受精卵は卵割という細胞増殖を繰り返す事で多細胞の胚を形成する[26]。一般的に卵割の際は核は複製されるが細胞質は卵細胞のものを分割して使うという特徴がある[26]。

一般的に、卵割が進むと胚の内部に隙間が形成され、この隙間が広くなったものを胞胚腔といい、大きな胞胚腔が形成される時期の胚は胞胚と呼ばれる[27]。なお、昆虫や両生類など多くの動物では、卵割期の細胞増殖を急激に行うために通常の細胞分裂で行われる一部の過程(G1期とG2期の過程)が省略され[28]、胞胚中期になるとこの省略が終わる(中期胞胚転移)[29]。それに対し胎生の哺乳類ではこういった省略は起こらない[29]。

胚が形成される過程で、体軸という体の向きが決定がなされ、その向きには前後軸、背腹軸、左右軸などがある[30]。例えば両生類では精子が受精した位置により背腹軸が決まり、受精した側が腹側、その反対側が背側になる。

一部の原始的な動物(前左右相称動物[注釈 2])以外は胞胚後期になると胚葉が形成される(形態形成運動)[31][32]。胚葉には将来消化管になる内胚葉、将来表皮や神経系などになる外胚葉、そして体のそれ以外の所(例えば体腔、循環系、内骨格、筋肉、真皮)になる中胚葉の3種類がある。典型的にはこの際内胚葉の部分が陥没し、原腸が構成される。この時期の胚を原腸胚という[注釈 3]。

なお、前左右相称動物の場合は、海綿動物のように胚葉が形成されないものや[33](無胚葉性の動物と呼ばれる)、内胚葉と外胚葉の2つのみしか形成されない動物(二胚葉性の動物)もいる[注釈 4]。これに対し胚葉が3つとも形成されるものを三胚葉性の動物という。

脊椎動物などではこの後神経管が形成される神経胚期へと進む。例えばニワトリでは、外胚葉に神経板という領域ができ、それが胚の内側に丸まる事で神経管ができ、さらに直下に脊索が形成される[34]。神経管の前方には前脳、中脳、後脳という3つの膨らみが形成され、これらが将来脳になる[35]。

細胞分化と器官形成

脊椎動物などでは、組織や器官を形成するため、胚細胞が特定の機能を持った細胞に変化する(細胞分化)[36]。この際、基本的な細胞機能の維持に必要な遺伝子(ハウスキーピング遺伝子)の機能は残しつつ、特定の機能に必要な遺伝子を新たに発現し、逆に分化後には不必要になる遺伝子をDNAメチル化により不活性化する[36]。

脊索の両側の沿軸中胚葉から体節が形成され、体節と隣接した外側の中間中胚葉からは腎節が形成される[37]。

体節はやがて皮節、筋節、硬節に分かれ、これらはそれぞれ皮膚の真皮層、骨格筋、椎骨などが形成され[37]、腎節からは腎臓や生殖腺が形成される[37]。

中間中胚葉のさらに外側には予定心臓中胚葉という、将来心臓関連の組織になる部分があり、これは壁側中胚葉と臓側中胚葉に転移する[38]。前者からは体腔を覆う胸膜や腹膜が形成され、後者からは心筋、平滑筋、血管、血球などが形成される[39]。

心臓は生命の維持に不可欠なので、発生の早い段階で中胚葉から形成される[40]。なお、予定心臓中胚葉は中胚葉の正中線を隔てた両側に2つ存在するが、これら2つは移動して胚の前方で合流して心臓を形成する[40]。

脊椎動物では外胚葉と中胚葉の相互作用で四肢が形成される[41]。ヒトの手足は水鳥と違い、指の間に水かきがないが、これはアポトーシスの作用で水かき部分の細胞を「自殺」させている為である[42]。

起源と進化

起源

動物の起源については、単細胞生物の襟鞭毛虫が集まって多細胞化する事で海綿動物のような動物になっていったと考えられる[43]。

なお従来は、上述した襟鞭毛虫類から進化したとするヘッケルの説と繊毛虫類から進化したとするハッジの説が対立していたが、分子遺伝学の成果によれば、18S rDNAに基づいた解析等により、動物は襟鞭毛虫類を姉妹群に持つ単系統な群であることが示されており、ヘッケルの説が有力とされている[43]。

古生物

30億年以上前に地球上初めての生物が誕生したと考えられており、真核生物の最古の化石は21億年前の地層から発見されている[44]。

動物の起源は10~12億年前まで遡れると分子系統解析と古生物学的証拠から推定されている[45]。

動物のものかもしれない最古の化石は南オーストラリア州から発見された6億6500万年のTrezona Formationで、初期のカイメンではないかと考えられている[46]

次に古いと思われる多細胞生物の化石は6億2千万年~5億4千2百万年前のエディアカラ生物群である[47]。これらは刺胞動物、環形動物、棘皮動物の仲間であるという解釈もあれば、一部には現生動物とは全く違う動物群とする解釈もあるなど見解が定まっていない[47]。 エディアカラ生物群は新原生代クライオジェニアン紀の全地球凍結(スノーボールアース)の後に進化的に拡散[訳語疑問点](Evolutionary radiation)したと考えられ(Avalon explosion、5億7500万年前)[48][49]、カンブリア爆発の頃にその多くは姿を消した(カンブリア中期の5億1000万年前~5億年前まで生き残っていたものはまれである)。

古生代のカンブリア紀になると、化石に残る硬い骨格を動物達が獲得し、短期間で多くのボディプランを持つ動物群が登場し[50]、海綿動物、軟体動物、腕足動物、節足動物、棘皮動物、環形動物、脊索動物など、現在の動物門のほとんどをしめる30余りの動物門が生じたとされる(カンブリア爆発[50]。

ただし分子系統解析によればこれらの動物門は最古の化石より10億年以上遡ると推定されている[50]。カンブリア紀に突然生物が増えたように見えるのは、この時期に化石に残りやすい生物種が増えたからに過ぎない [51][52][53][54]

カンブリア爆発は2000万年[55][56]から2500万年[57][58]続いた。オルドビス紀にはカンブリア紀までに登場した動物門が大きく適応放散している[50]。

オルドビス紀末に大量絶滅(O-S境界)があったが[50]、無顎類(顎の無い脊椎動物)は生き残り、シルル紀に多様化し、顎のある脊椎動物も登場した[50]。デボン紀には硬骨魚類が多様化し、石炭紀には両生類が繁栄、ペルム紀には爬虫類が繁栄した[50]。

シルル紀には最古の陸上動物の化石である節足動物多足類が登場し、デボン紀に節足動物が多様化、石炭紀には翅を持つ昆虫類が登場した[50]。

シルル紀末には地球史上最大の大量絶滅(P-T境界)が起こり、中生代三畳紀には海洋生物が大量に絶滅[50]。哺乳類が登場した[50]。

ジュラ紀には恐竜が反映し、鳥類も登場した[50]。また、軟体動物の殻を破るカニ類や硬骨魚類が進化し、これに対抗して厚い殻をもつれ合い軟体動物が進化した(中世代の海洋変革)[50]。白亜紀までには現生の昆虫類のほとんどが登場[50]。

白亜紀末には巨大隕石の衝突による大量絶滅がおこる(K-Pg境界)[50]。

新生代は哺乳類が優勢になり、鳥類、昆虫類、真骨魚類も適応放散し、現在と同様の動物相が形成される[50]。新生代の後半にあたる第四紀には人類も出現した。

化石動物についての動物門

化石動物について、上記の分類される現存動物門のいずれにも属さないとして、新たな動物門が提唱されることがある。これらについては、うたかたのごとく提唱されては消えていくものも少なくないが、主なもののみ挙げる。

- †三裂動物門 Trilobozoa Fedonkin,1985

- トリブラキディウムなどが属する。三放射対称の体制をもつ。

- †盾状動物門 Proarticulata Fedonkin,1985

- †古虫動物門 Vetulicolia Shu, et al. 2001

- †葉足動物門 Lobopodia Snodgrass, 1938

絶滅した動物

現生の動物の分類

分類

下表は動物界を生物の分類の分類階級である「門」に分類したものであり[62]、各動物門に属する生物はそれぞれの「門」独自の基本設計(ボディプラン)を共有している。

ただし、2018年現在、分子系統解析が進展中ということもあり、下表は今後も若干の修正が加えられていくものと思われる。

| 上位分類 | 門 | 種の数 | 動物の例 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 後生動物 | (前左右相称動物)[注釈 2] | 海綿動物門 | 約7000種[64] |  カイメン、 カイメン、 カイロウドウケツ カイロウドウケツ

| ||

| 平板動物門 | 1種[65] | |||||

| 刺胞動物門 | 約7620種[66] |  クラゲ、 クラゲ、 サンゴ サンゴ

| ||||

| 有櫛動物門 | 約143種[67] |  クシクラゲ クシクラゲ

| ||||

| 左右相称動物 | 冠輪動物 | ? | 直泳動物門 | 25種[68] |  キリオキンクタ キリオキンクタ

| |

| ? | 菱形動物門[68]

(二胚動物門とも) |

約110種[68] |  ニハイチュウ ニハイチュウ

| |||

| 扁平動物 | 扁形動物門 | 約20000種[69] |  サナダムシ サナダムシ

| |||

| 顎口動物門 | 約100種[70] | |||||

| 輪形動物門 | 約3000種[71] |  ワムシ ワムシ

| ||||

| 鉤頭動物 | 約1100種[72] |

| ||||

| 微顎動物門 | 1種[73] | |||||

| 腹毛動物門 | 約450種[74] |  イタチムシ、オビムシ イタチムシ、オビムシ

| ||||

| ? | 外肛動物門 | 約4500種[75] |  コケムシ コケムシ

| |||

| 触手冠動物 | 箒虫動物門 | 約20種[76] |  ホウキムシ ホウキムシ

| |||

| 腕足動物門 | 約350種[76] |  シャミセンガイ、ホオズキガイ シャミセンガイ、ホオズキガイ

| ||||

| 担輪動物 | 紐形動物門 | 約1200種[77] | ||||

| 軟体動物門 | 約93195種[78] |  貝類、 貝類、 イカ、 イカ、 タコ タコ

| ||||

| 星口動物門 | 約320種[79] |  ホシムシ ホシムシ

| ||||

| 環形動物門 | 約16650種[注釈 5] |  ミミズ、 ミミズ、 ゴカイ、 ゴカイ、 ユムシ ユムシ

| ||||

| 内肛動物門 | 約150種[80] |  スズコケムシ スズコケムシ

| ||||

| 有輪動物門 | 2種[81] | シンビオン | ||||

| 脱皮動物 | 線形動物 | 線形動物門 | 約15000種[82] |  回虫 回虫

| ||

| 類線形動物門 | 約320種[83] |  ハリガネムシ ハリガネムシ

| ||||

| 有棘動物 | 動吻動物門 | 約150種[84] | トゲカワ | |||

| 胴甲動物門 | 約23種[85] |  コウラムシ コウラムシ

| ||||

| 鰓曳動物門 | 約16種[86] |  エラヒキムシ エラヒキムシ

| ||||

| 汎節足動物 | 緩歩動物門 | 約800種[87] |  クマムシ クマムシ

| |||

| 有爪動物門 | 約160種[88] |  カギムシ カギムシ

| ||||

| 節足動物門 | 約110万種[89] |  昆虫類、 昆虫類、 | ||||

| ? | 毛顎動物門 | 約130種[90] | ||||

| 新口動物 | 珍無腸動物門 | 無腸動物、珍渦虫 | ||||

| 棘皮動物門 | 約7000種[91] |  ヒトデ、 ヒトデ、 ナマコ、 ナマコ、 ウニ ウニ

| ||||

| 半索動物門 | 約90種[92] |  ギボシムシ、フサカツギ ギボシムシ、フサカツギ

| ||||

| 脊索動物門 | 約51416種[93] |  ナメクジウオ、 ナメクジウオ、 ホヤ、 ホヤ、 脊椎動物 脊椎動物

| ||||

なお、上述の分類において

- 左右相称動物は体腔の違いにより、旧口動物、新口動物に分けられていたが、1990年代の18S rRNA遺伝子の解析により、体腔の違いは進化とは関係ない事が判明し、冠輪動物、脱皮動物、新口動物の3つに大別されることが分かった[94]。しかし以降の系統解析でも、旧口動物が単系統であること自体は支持されている[95][96][97]。

- 刺胞動物と有櫛動物は外形的に類似しているので腔腸動物門としてまとめられていたが、有櫛動物は刺胞がなく、上皮細胞が多繊毛性であり、決定性卵割であるといった刺胞動物との決定的違いがあり、しかも分子系統解析により腔腸動物が単系統とならないがわかったので2010年現在は両者は別の門として分けられている[98]

- 中生動物門は直泳動物門と二胚動物門に分けられている[62]。なお中生動物門は原生動物から後生動物に進化する過程であると過去には見られていたが、2010年現在では寄生生活により退化した後生動物であると見られている[99]。

- 外肛動物は触手冠動物とされてきたが、箒虫動物や腕足動物のような他の触手冠動物どは異なる系統である事がわかった[100]。2010年現在系統上の一は定まっていない[100]。

- 有髭動物門とユムシ動物門は環形動物門に入れられている[62][63]。

- 舌形動物門は節足動物門に入れられている[62]。

- かつて扁形動物門に分類されていた珍渦虫と無腸動物については、新口動物の新たな門として珍無腸動物門が設立された[101][102]。しかし2016年の2つの分子系統解析は、珍無腸動物門が他の左右相称動物の姉妹群となることを支持した[103][95]。

各門の特徴とさらなる分類

この節はただいま大幅な改稿を行っています。 申し訳ございませんが編集の競合を避けるため、7月中編集を控えてくださるとありがたく存じます。 設定期限もしくは貼付後72時間経っても工事が完了していない場合は、このテンプレートを除去しても構いません。 |

Phylogeny

Animals are monophyletic, meaning they are derived from a common ancestor and form a single clade within the Apoikozoa. The Choanoflagellata are their sister clade.[104] The most basal animals, the Porifera, Ctenophora, Cnidaria, and Placozoa, have body plans that lack bilateral symmetry, but their relationships are still disputed. As of 2017, the Porifera are considered the basalmost animals.[105][106][107][108][109][110] An alternative to the Porifera could be the Ctenophora,[111][112][113][114] which like the Porifera lack hox genes, important in body plan development. These genes are found in the Placozoa[115][116] and the higher animals, the Bilateria.[117][118] 6,331 groups of genes common to all living animals have been identified; these may have arisen from a single common ancestor that lived 650 million years ago in the Precambrian. 25 of these are novel core gene groups, found only in animals; of those, 8 are for essential components of the Wnt and TGF-beta signalling pathways which may have enabled animals to become multicellular by providing a pattern for the body's system of axes (in three dimensions), and another 7 are for transcription factors including homeodomain proteins involved in the control of development.[119][120]

The phylogenetic tree (of major lineages only) indicates approximately how many millions of years ago (mya) the lineages split.[121][122][123][124]

| Apoikozoa |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 950 mya |

Ctenophora.2C_Porifera.2C_Placozoa.2C_Cnidaria_and_Bilateria

Non-bilaterian animals

Several animal phyla lack bilateral symmetry. Among these, the sponges (Porifera) probably diverged first, representing the oldest animal phylum.[125] Sponges lack the complex organization found in most other animal phyla;[126] their cells are differentiated, but in most cases not organised into distinct tissues.[127] They typically feed by drawing in water through pores.[128]

The Ctenophora (comb jellies) and Cnidaria (which includes jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals) are radially symmetric and have digestive chambers with a single opening, which serves as both mouth and anus.[129] Animals in both phyla have distinct tissues, but these are not organised into organs.[130] They are diploblastic, having only two main germ layers, ectoderm and endoderm.[131] The tiny placozoans are similar, but they do not have a permanent digestive chamber.[132][133]

Bilaterian animals

The remaining animals, the great majority – comprising some 29 phyla and over a million species – form a clade, the Bilateria. The body is triploblastic, with three well-developed germ layers, and their tissues form distinct organs. The digestive chamber has two openings, a mouth and an anus, and there is an internal body cavity, a coelom or pseudocoelom. Animals with this bilaterally symmetric body plan and a tendency to move in one direction have a head end (anterior) and a tail end (posterior) as well as a back (dorsal) and a belly (ventral); therefore they also have a left side and a right side.[134][135]

Having a front end means that this part of the body encounters stimuli, such as food, favouring cephalisation, the development of a head with sense organs and a mouth. Many bilaterians have a combination of circular muscles that constrict the body, making it longer, and an opposing set of longitudinal muscles, that shorten the body;[135] these enable soft-bodied animals with a hydrostatic skeleton to move by peristalsis.[136] They also have a gut that extends through the basically cylindrical body from mouth to anus. Many bilaterian phyla have primary larvae which swim with cilia and have an apical organ containing sensory cells. However, there are exceptions to each of these characteristics; for example, adult echinoderms are radially symmetric (unlike their larvae), while some parasitic worms have extremely simplified body structures.[134][135]

Genetic studies have considerably changed zoologists' understanding of the relationships within the Bilateria. Most appear to belong to two major lineages, the protostomes and the deuterostomes.[137] The basalmost bilaterians are the Xenacoelomorpha.[138][139][140]

Protostomes and deuterostomes

Protostomes and deuterostomes differ in several ways. Early in development, deuterostome embryos undergo radial cleavage during cell division, while many protostomes (the Spiralia) undergo spiral cleavage.[141] Animals from both groups possess a complete digestive tract, but in protostomes the first opening of the embryonic gut develops into the mouth, and the anus forms secondarily. In deuterostomes, the anus forms first while the mouth develops secondarily.[142][143] Most protostomes have schizocoelous development, where cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm. In deuterostomes, the mesoderm forms by enterocoelic pouching, through invagination of the endoderm.[144]

The main deuterostome phyla are the Echinodermata and the Chordata.[145] Echinoderms are exclusively marine and include starfish, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers.[146] The chordates are dominated by the vertebrates (animals with backbones),[147] which consist of fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.[148] The deuterostomes also include the Hemichordata (acorn worms).[149][150]

Ecdysozoa

The Ecdysozoa are protostomes, named after their shared trait of ecdysis, growth by moulting.[151] They include the largest animal phylum, the Arthropoda, which contains insects, spiders, crabs, and their kin. All of these have a body divided into repeating segments, typically with paired appendages. Two smaller phyla, the Onychophora and Tardigrada, are close relatives of the arthropods and share these traits. The ecdysozoans also include the Nematoda or roundworms, perhaps the second largest animal phylum. Roundworms are typically microscopic, and occur in nearly every environment where there is water;[152] some are important parasites.[153] Smaller phyla related to them are the Nematomorpha or horsehair worms, and the Kinorhyncha, Priapulida, and Loricifera. These groups have a reduced coelom, called a pseudocoelom.[154]

Spiralia

The Spiralia are a large group of protostomes that develop by spiral cleavage in the early embryo.[155] The Spiralia's phylogeny has been disputed, but it contains a large clade, the superphylum Lophotrochozoa, and smaller groups of phyla such as the Rouphozoa which includes the gastrotrichs and the flatworms. All of these are grouped as the Platytrochozoa, which has a sister group, the Gnathifera, which includes the rotifers.[156][157]

The Lophotrochozoa includes the molluscs, annelids, brachiopods, nemerteans, bryozoa and entoprocts.[156][158][159] The molluscs, the second-largest animal phylum by number of described species, includes snails, clams, and squids, while the annelids are the segmented worms, such as earthworms, lugworms, and leeches. These two groups have long been considered close relatives because they share trochophore larvae.[160][161]

History of classification

In the classical era, Aristotle divided animals,[注釈 7] based on his own observations, into those with blood (roughly, the vertebrates) and those without. The animals were then arranged on a scale from man (with blood, 2 legs, rational soul) down through the live-bearing tetrapods (with blood, 4 legs, sensitive soul) and other groups such as crustaceans (no blood, many legs, sensitive soul) down to spontaneously-generating creatures like sponges (no blood, no legs, vegetable soul). Aristotle was uncertain whether sponges were animals, which in his system ought to have sensation, appetite, and locomotion, or plants, which did not: he knew that sponges could sense touch, and would contract if about to be pulled off their rocks, but that they were rooted like plants and never moved about.[163]

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus created the first hierarchical classification in his Systema Naturae.[164] In his original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of Vermes, Insecta, Pisces, Amphibia, Aves, and Mammalia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the Chordata, while his Insecta (which included the crustaceans and arachnids) and Vermes have been renamed or broken up. The process was begun in 1793 by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck, who called the Vermes une espèce de chaos (a sort of chaos)[注釈 8] and split the group into three new phyla, worms, echinoderms, and polyps (which contained corals and jellyfish). By 1809, in his Philosophie Zoologique, Lamarck had created 9 phyla apart from vertebrates (where he still had 4 phyla: mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish) and molluscs, namely cirripedes, annelids, crustaceans, arachnids, insects, worms, radiates, polyps, and infusorians.[162]

In his 1817 Le Règne Animal, Georges Cuvier used comparative anatomy to group the animals into four embranchements ("branches" with different body plans, roughly corresponding to phyla), namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals (arthropods and annelids), and zoophytes (echinoderms, cnidaria and other forms).[166] This division into four was followed by the embryologist Karl Ernst von Baer in 1828, the zoologist Louis Agassiz in 1857, and the comparative anatomist Richard Owen in 1860.[167]

In 1874, Ernst Haeckel divided the animal kingdom into two subkingdoms: Metazoa (multicellular animals, with five phyla: coelenterates, echinoderms, articulates, molluscs, and vertebrates) and Protozoa (single-celled animals), including a sixth animal phylum, sponges.[168][167] The protozoa were later moved to the former kingdom Protista, leaving only the Metazoa as a synonym of Animalia.[169]

In human culture

The human population exploits a large number of other animal species for food, both of domesticated livestock species in animal husbandry and, mainly at sea, by hunting wild species.[170][171] Marine fish of many species are caught commercially for food. A smaller number of species are farmed commercially.[170][172][173] Invertebrates including cephalopods, crustaceans, and bivalve or gastropod molluscs are hunted or farmed for food.[174] Chickens, cattle, sheep, pigs and other animals are raised as livestock for meat across the world.[171][175][176] Animal fibres such as wool are used to make textiles, while animal sinews have been used as lashings and bindings, and leather is widely used to make shoes and other items. Animals have been hunted and farmed for their fur to make items such as coats and hats.[177][178] Dyestuffs including carmine (cochineal),[179][180] shellac,[181][182] and kermes[183][184] have been made from the bodies of insects. Working animals including cattle and horses have been used for work and transport from the first days of agriculture.[185]

Animals such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster serve a major role in science as experimental models.[186][187][188][189] Animals have been used to create vaccines since their discovery in the 18th century.[190] Some medicines such as the cancer drug Yondelis are based on toxins or other molecules of animal origin.[191]

People have used hunting dogs to help chase down and retrieve animals,[192] and birds of prey to catch birds and mammals,[193] while tethered cormorants have been used to catch fish.[194] Poison dart frogs have been used to poison the tips of blowpipe darts.[195][196] A wide variety of animals are kept as pets, from invertebrates such as tarantulas and octopuses, insects including praying mantises,[197] reptiles such as snakes and chameleons,[198] and birds including canaries, parakeets and parrots[199] all finding a place. However, the most kept pet species are mammals, namely dogs, cats, and rabbits.[200][201][202] There is a tension between the role of animals as companions to humans, and their existence as individuals with rights of their own.[203] A wide variety of terrestrial and aquatic animals are hunted for sport.[204]

Animals have been the subjects of art from the earliest times, both historical, as in Ancient Egypt, and prehistoric, as in the cave paintings at Lascaux. Major animal paintings include Albrecht Dürer's 1515 The Rhinoceros, and George Stubbs's c. 1762 horse portrait Whistlejacket.[205] Insects, birds and mammals play roles in literature and film,[206] such as in giant bug movies.[207][208][209] Animals including insects[210] and mammals[211] feature in mythology and religion. In both Japan and Europe, a butterfly was seen as the personification of a person's soul,[210][212][213] while the scarab beetle was sacred in ancient Egypt.[214] Among the mammals, cattle,[215] deer,[211] horses,[216] lions,[217] bats[218] and wolves[219] are the subjects of myths and worship. The signs of the Western and Chinese zodiacs are based on animals.[220][221]

前左右相称動物

前左右相称動物[注釈 2]に属する4つの門の間の関係、およびこれら4つの門と左右相称動物との関係は2010年現在、分子系統解析でも定まっていない[222]。

- 海綿動物

- 相称性がなく胚葉がないなど最も単純なボディープランを持つので、最も祖先的で最初に分化した後生動物だと考えられる事が多い[223]

- 平板動物

- 1mm程度の薄い板上の多細胞動物で、センモウヒラムシ1種のみとされるが、様々な地域から見つかるため複数種である可能性も高い[224]

- 刺胞動物

- 有櫛動物

左右相称動物

完全な三胚葉性で[100]、体が左右相称[100]。扁形動物は多系統群であり、その中の無腸型類が左右相称動物の中で最も祖先的である事が2010年現在わかりつつある[100]。

冠輪動物

直泳動物・二胚動物

扁平動物

もともとは扁形動物門、輪形動物門、鉤頭動物門に対して名付けられた門で、これら3つには体表に繊毛があり、体節がなく、循環系を欠き、無体腔または偽体腔であるという特徴がある[227]。顎口動物門、輪形動物門、鉤頭動物門の系統上の位置は2010年現在安定していないが、扁形動物の一部と近縁であると考えられている[100]。

外肛動物

触手冠動物

担輪動物

- 紐形動物 - 以下の2つに分類される[228]

- 軟体動物

- 三胚葉性[229]。真体腔を持つ(退化的である事が多い)[229]。体節がない[229]。骨格がなく軟体[229]。

- 一般的には体は頭部、内蔵塊、足からなり[229]、外套膜が内蔵塊を覆っている[229]。外套膜が分泌した石灰質の貝殻を持つ事が多い[229]。

- 8つの綱からなる。定説には達していないものの、8つの綱は一般的には2つの亜門に分類される[229]

- 双神経亜門:祖先的なボディープランを残している[229]

- 貝類亜門:殻皮と石灰質の層状の貝殻を持つ[229]

- 単板綱:現生種はネオピリナなど数十種[229]。化石種は多数知られる[229]

- 頭足類:体が前後に伸び[229]、外套膜は内蔵塊包み胴部を形成[229]。口の周囲に触手ないし腕がある[229]。外套腔は前方に開き、腹側に筒状の漏斗を備える(水を吐いて移動したり、墨をはいたりするのに利用)[229]。貝殻はオウムガイ以外では通常体内にあるか完全に退化[229]。外套腔に鰓[229]。精巧な眼を持つ[229]。オウムガイ類、タコ類、イカ類、絶滅したアンモナイト類など[229]

- 腹足綱:通常は螺旋状に巻いた貝殻と蓋を持つ。カサガイ、サザエ、クロアワビ、オキナエビス、有肺類(カタツムリ、ナメクジなど)、後鰓類(ウミウシなど)を含む[229]

- 掘足綱:ツノガイの仲間[229]

- 二枚貝綱:左右に外套膜が張り出し、そこから分泌される2枚の貝殻が体の左右を覆っている[229]。ムラサキイガイ、アコヤガイ、マガキ、オカメブンブクヤドリガイ、オオシャコガイ、フナクイムシなど[229]

- 星口動物

- 環形動物

- 内肛動物

- 有輪動物

脱皮動物

体を覆うクラチラの脱皮を行うという共通の特徴を持つ[100]。脱皮動物内の系統は2010年現在はっきりしないが、分子系統解析と形態から総合的に考えて線形動物、有棘動物、汎節足動物の3つに分類がなされている[100]。毛顎動物の系統は2010年現在不明だが、節足動物との近縁性が示唆されれる成果もある[100]。

線形動物

- 線形動物 - 以下の2つに分類される[230]:

- 類線形動物 - 以下の2つに分類される[231]:

- ハリガネムシ目:寄生生活を送る。水生昆虫を中間宿主とし、カマキリなどを終宿主とする。

- *遊線虫目:生活史の詳細は不明。

有棘動物

- 動吻動物 - 動吻動物はトゲカワ類、キョクヒチュウ (棘皮虫)とも呼ばれ、頸部のクラチラ膜の枚数などによってキクロラグ目とホマロラグ目に分類される[232]。

- 胴甲動物 - 日本からの正式な記載はシンカイシワコウラムシのみ[232]

- 鰓曳動物 - 日本からはエラヒキムシとフタツエラヒキムシの2種のみ[233]

汎節足動物

- 緩歩動物 - 緩歩動物門に属する動物はクマムシとも呼ばれ、以下の3綱に分類される[234]。

- 異クマムシ綱:多くは海に住む

- 中クマムシ綱:オンセンクマムシ一種のみ

- 真クマムシ綱:陸上、淡水に生息するものがほとんど

- 有爪動物 - 有爪動物門に属する動物はカギムシと呼ばれる。カンブリア紀に多様化したが、現生種は真有爪目のみ[235]。

- 節足動物

毛顎動物

新口動物