「生命」の版間の差分

m 外部リンクの修正 http:// -> https:// (www.webcitation.org) (Botによる編集) |

→外部リンク: 補記。 |

||

| (2人の利用者による、間の11版が非表示) | |||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

{{ |

{{Otheruses|生きているものを指す概念|1994年の[[NHKスペシャル]]|生命40億年はるかな旅|松山千春の曲|生命 (松山千春の曲)}} |

||

{{生物分類表 |

|||

{{導入部が短い|date=2018年10月}} |

|||

|名称 = 生命<br/><font style="font-size: 95%;line-height: 95%;">Life</font> |

|||

{{出典の明記|date=2012年11月}} |

|||

|fossil_range = {{Long fossil range|3770|0|earliest=4280}} <font style="font-size: 90%;line-height: 90%;">[[太古代]] – [[完新世|現在]] ([[冥王代]]起源の可能性あり)</font> |

|||

[[File:Human fetus 10 weeks - therapeutic abortion.jpg|thumb|right|[[妊娠]]第10週目の[[ヒト]]の[[胎児]]。]] |

|||

|色 = 所属不明 |

|||

|画像 = [[File:Coral reef... South end of my area (14119221571).jpg|220px]] |

|||

|画像キャプション = [[サンゴ礁]]の多様な生物形態 |

|||

|taxon = Life |

|||

|authority = |

|||

|下位分類名 = [[ドメイン (生物学)|ドメイン]]と[[スーパーグループ (分類学)|スーパーグループ]] |

|||

|下位分類 = 地球の生命:<font style="font-size: 95%;line-height: 95%;"> |

|||

* [[細胞|細胞生命]]<!-- Cellular life --> |

|||

** ドメイン [[細菌]] <!-- Domain Bacteria --> |

|||

** ドメイン [[古細菌]]<!-- Domain Archaea --> |

|||

** ドメイン [[真核生物]]<!-- Domain Eukaryota --> |

|||

*** [[アーケプラスチダ]]<!-- Archaeplastida --> |

|||

**** [[植物界]]<!-- Plantae --> |

|||

*** [[SARスーパーグループ]]<!-- SAR supergroup --> |

|||

*** [[エクスカバータ]]<!-- Excavata --> |

|||

*** [[アメーボゾア]]<!-- Amoebozoa --> |

|||

*** [[オピストコンタ]]<!-- Opisthokont --> |

|||

**** [[ホロマイコータ]]<!-- Holomycota --> |

|||

***** [[菌界]]<!-- Fungi --> |

|||

**** [[ホロゾア]]<!-- Holozoa --> |

|||

***** [[動物界]]<!-- Animalia --> |

|||

* {{ill2|非細胞生命|en|Non-cellular life}}<!-- Non-cellular life --> |

|||

** [[ウイルス]]{{efn|ウイルスは共通祖先から派生したものではないと強く信じられており、それぞれの{{ill2|域 (ウイルス学)|en|Realm (virology)|label=域}}はウイルスの別々の種が誕生したことに対応している<ref name=exec >{{cite journal |author=International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Executive Committee |date=May 2020 |title=The New Scope of Virus Taxonomy: Partitioning the Virosphere Into 15 Hierarchical Ranks |journal=Nature Microbiology |volume=5 |issue=5 |pages=668–674 |doi=10.1038/s41564-020-0709-x |pmc=7186216 |pmid=32341570}}</ref>。}} |

|||

** {{ill2|ウイルソイド|en|Virusoid}}<!-- Virusoid --> |

|||

** [[ウイロイド]]<!-- Viroid --> |

|||

</font> |

|||

}} |

|||

'''生命'''(せいめい、{{Lang-en-short|life}})とは、[[シグナル伝達]]や自立過程などの[[生物学的プロセス|生物学的現象]]を持つ[[物質]]を、そうでない物質と区別する性質であり、[[恒常性]]、[[生命の階層|組織化]]、[[代謝]]、{{Ill2|細胞成長|en|Cell growth|label=成長}}、[[適応 (生物学)|適応]]、{{Ill2|刺激 (物理学)|en|Stimulus (physiology)|label=刺激}}に対する反応、および[[生殖]]の能力によって記述的に定義される。[[自己組織化|自己組織化系]]など、{{Ill2|生体系|en|Living systems}}の多くの哲学的定義が提案されている。[[ウイルス]]は特に、[[宿主]]細胞内でのみ複製するため定義が困難である。生命は大気、水、[[土壌]]など、地球上のあらゆる場所に存在し、多くの[[生態系]]が[[生物圏]]を形成している。これらの中には、[[極限環境微生物]]だけが生息する過酷な環境もある。 |

|||

'''生命'''(せいめい、{{Lang-en-short|life}}、{{Lang-la-short|vita}} ウィータ)とは一般に[[生物]]及び[[生命体]]が生きていくための[[根源]]的な力。ここでは幅広く[[意味]]を持つ生命について詳しく[[解説]]する。 |

|||

生命は古代から研究されており、[[エンペドクレス]]は[[唯物論]]で、生命は[[四元素|永遠の四元素]]から構成されていると主張し、[[アリストテレス]]は{{Ill2|質料形相論|en|Hylomorphism|preserve=1}}で、生物には魂があり、[[イデア論|形]]と物質の両方を体現していると主張した。生命は少なくとも35億年前に[[生命の起源|誕生]]し、その結果、{{Ill2|最終普遍共通祖先|en|Last universal common ancestor|label=普遍的な共通祖先}}へとつながった。これが、多くの[[絶滅種]]を経て、現存するすべての[[種 (分類学)|種]]へと進化し、その一部は[[化石]]として痕跡を残している。また、生物を分類する試みも{{Ill2|アリストテレスの生物学|en|Aristotle's biology|label=アリストテレスから始まった}}。現代の[[分類体系|分類]]は、1740年代の[[カール・リンネ]]による[[二名法]]から始まった。 |

|||

== 概論 == |

|||

生命とは、[[文脈]]によって様々な[[定義]]がある語であるが、基本的には「生きているもの」と「死んでいるもの」、あるいは[[物質]]と[[生物]]を区別する特徴・[[属性]]などを指す語、あるいは[[抽象化|抽象概念]]である。伝統的に、「生き物が生きた状態」そのものを生命と呼んだり、生きた状態は目に見えない何かが宿っている状態であるとして、その宿っているものを「生命」「[[命]]」「[[魂]]」などと呼んでおり、現在でも広く日常的にそのような用法で使われている。現代の[[生物学]]では、[[代謝]]に代表される、自己の維持、増殖、[[自己]]と外界との隔離など、様々な現象の連続性を以って「生命」とする場合が多い。 |

|||

生物は[[生化学|生化学的]]な[[分子]]で構成されており、主に少数の核となる[[化学元素]]から形成されている。すべての生物には、[[タンパク質]]と[[核酸]]という2種類の大きな分子が含まれており、後者は通常、[[デオキシリボ核酸|DNA]]と[[リボ核酸|RNA]]の両方がある。核酸は、各種のタンパク質を作るための命令など、それぞれの生物種に必要な情報を伝達する役割がある。タンパク質も同様に、生命の多くの化学的過程を遂行する機械としての役割を果たす。[[細胞]]は生命の構造的および機能的な単位である。[[原核生物]]([[細菌]]や[[古細菌]])を含む微小な生物は、小さな単細胞で構成されている。より大きな[[生物]]、主に[[真核生物]]は、単細胞からなることもあれば、より複雑な構造を持つ[[多細胞生物|多細胞]]である場合もある。生命は地球上でしか存在が確認されていないが、[[地球外生命体]]の存在は[[フェルミのパラドックス|ありうると考えられている]]。[[人工生命]]は科学者や技術者によってシミュレートされ、研究されている。 |

|||

生命とは何か、ということについての論や見解を生命論や[[#生命観・生命論の歴史|生命観]]と言う。[[自然哲学]]には自然哲学の生命観があり、[[宗教]]には宗教的な生命観がある。現在、一般的・日常的には、生きものが生きている状態を指して「生命を持っている」「生命を宿している」と呼び、文脈によっては非物質的な[[魂]]のようなものを指す場合もある。 |

|||

__TOC__ |

|||

ここでは様々な角度から生命を扱うことにし、伝統的な概念から、現代生物学的な生命に関する概念や理論までを、ある程度歴史に沿って追ってゆくことにする。 |

|||

== 定義 == |

|||

{{main2|伝統的な理解については[[命]]、[[魂]]も}} |

|||

=== 課題 === |

|||

[[大島泰郎]]によれば、現在、我々[[人類]]が知っている生命は、[[地球]]上の[[生物]]のみであるが、これらの全ての生物は同一の[[先祖]]から発展してきたと、[[現代生物学]]では考えられている。その理由は、全ての地球生物が用いる[[アミノ酸]]が20種類だけに限定され、そのうち[[グリシン]]を除き[[光学異性体]]を持つ19種類が全てL型を選択していること、また[[DNA]]に用いる核酸の[[塩基]]が4種類に限定され、それらが全てD型である事である<ref name="Oshima14">[[#大島(1994)|大島(1994)、p.14-29、第1章 生命は星の一部である、(1)宇宙の生命を探る]]</ref>。 |

|||

生命の定義は、科学者や哲学者にとって長年の課題であった<ref name="Definitions 2009">{{cite journal |title=Why Is the Definition of Life So Elusive? Epistemological Considerations |journal=Astrobiology |date=May 2009 |last=Tsokolov |first=Serhiy A. |volume=9 |issue=4 |doi=10.1089/ast.2007.0201 |bibcode=2009AsBio...9..401T |pages=401–412 |pmid=19519215}}</ref><ref name="Emmeche1997">{{cite web |first1=Claus |last1=Emmeche |date=1997 |title=Defining Life, Explaining Emergence |publisher=Niels Bohr Institute |url=http://www.nbi.dk/~emmeche/cePubl/97e.defLife.v3f.html |access-date=25 May 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120314095044/http://www.nbi.dk/~emmeche/cePubl/97e.defLife.v3f.html |archive-date=14 March 2012 }}</ref><ref name="McKay">{{Cite journal |title=What Is Life—and How Do We Search for It in Other Worlds? |journal=PLOS Biology |date=14 September 2004 |first=Chris P. |last=McKay |pmid=15367939 |volume=2 |issue=9 |pmc=516796 |page=302 |doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0020302 |doi-access=free }}</ref>。その理由の一つは、生命は物質ではなく過程(プロセス)であるためである<ref name="DefinitionMotivation">{{Cite journal |last=Mautner |first=Michael N. |title=Directed panspermia. 3. Strategies and motivation for seeding star-forming clouds |journal=Journal of the British Interplanetary Society |date=1997 |volume=50 |pages=93–102 |url=http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFDirectedPanspermia3JBIS1997Paper.pdf |bibcode=1997JBIS...50...93M |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121102064738/http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFDirectedPanspermia3JBIS1997Paper.pdf |archive-date=2 November 2012 }}</ref><ref name="SeedingBook">{{Cite book |last=Mautner |first=Michael N. |title=Seeding the Universe with Life: Securing Our Cosmological Future |location=Washington D.C. |date=2000 |isbn=978-0-476-00330-9 |url=http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFSeedingtheUniverse2005Book.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121102064713/http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFSeedingtheUniverse2005Book.pdf |archive-date=2 November 2012 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=What is life? It's a Tricky, Often Confusing Question |journal=Astrobiology Magazine |date=18 September 2014 |last=McKay |first=Chris}}</ref>。さらに、地球外で発生した可能性のある生命体の特徴(もしあるとすれば)が分からないことも、この問題を複雑にしている<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Nealson |first1=K.H. |last2=Conrad |first2=P.G. |title=Life: past, present and future |journal=[[:en:Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B|Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B]] |volume=354 |issue=1392 |pages=1923–1939 |date=December 1999 |pmid=10670014 |pmc=1692713 |doi=10.1098/rstb.1999.0532 |url=https://royalsociety.org/journals/|archive-date=3 January 2016 |archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20160103000925/https://royalsociety.org/journals/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Bioethics">{{Cite journal |last=Mautner |first=Michael N. |title=Life-centered ethics, and the human future in space |journal=Bioethics |volume=23 |pages=433–440 |date=2009 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00688.x |pmid=19077128 |url=http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFLifeCenteredBioethics2009Paper.pdf |issue=8 |s2cid=25203457 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121102064743/http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFLifeCenteredBioethics2009Paper.pdf |archive-date=2 November 2012 }}</ref>。生命の哲学的な定義も提唱されているが、生物と非生物を区別する上で同様の困難を抱えている<ref name="Jeuken1975">{{cite journal|title=The biological and philosophical defitions of life |author=Jeuken M |journal=Acta Biotheoretica |volume=24 |issue=1–2 |pages=14–21 |date=1975 |doi=10.1007/BF01556737|pmid=811024 |s2cid=44573374 }}</ref>。[[認定死亡|法的な生命の定義]]については議論がなされているが、主に人間の死を宣告するための決定と、その決定がもたらす法的影響に焦点が当てられている<ref name="Capron1978">{{cite journal|title=Legal definition of death |author=Capron AM |journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences |date=1978 |doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb50352.x |pmid=284746 |volume=315 |issue=1 |pages=349–362 |bibcode=1978NYASA.315..349C |s2cid=36535062 }}</ref>。少なくとも123の生命の定義がまとめられている<ref name="JBSD-20110317">{{cite journal |last=Trifonov |first=Edward N. |title=Vocabulary of Definitions of Life Suggests a Definition |date=17 March 2011 |journal=Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics |volume=29 |issue=2 |pages=259–266 |doi=10.1080/073911011010524992 |pmid=21875147 |doi-access=free }}</ref>。 |

|||

現在知られている地球上の全ての生物は[[炭素]]を素にしているが、我々が[[地球外生命体|地球以外での生命]]の形を知らないだけという可能性も指摘されることがある。理論上は炭素以外の物質を元とした生物も考えられうる。 |

|||

=== 記述的 === |

|||

{{seealso|代わりの生化学}} |

|||

{{further|生物<!--Organism-->}} |

|||

== 定義 == |

|||

生命の定義は[[哲学]]、[[生物学]]双方の分野で、非常に困難な問題である<ref>[http://www.astrobio.net/exclusive/226/defining-life Defining Life : Astrobiology Magazine - earth science - evolution distribution Origin of life universe - life beyond]</ref><ref>[http://www.nbi.dk/~emmeche/cePubl/97e.defLife.v3f.html Defining Life, Explaining Emergence]</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://artsandsciences.colorado.edu/magazine/2009/03/can-we-define-life/|title=Can We Define Life|accessdate=2009-06-22|year=2009|publisher=Colorado Arts & Sciences}}</ref>。生命とは何らかの過程を意味するものであり、純粋な物質というわけではないからである<ref name="McKay">{{cite journal|title=What Is Life—and How Do We Search for It in Other Worlds?|journal=PLoS Biol.|date=September 14, 2004|first=Chris P.|last=McKay|coauthors=|volume=2|issue=2(9)|pages=302|id=PMID PMC516796 {{doi|10.1371/journal.pbio.0020302}}|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC516796/?tool=pubmed|format=|accessdate=2010-02-02}}</ref>。また、地球以外で生み出された生命体についての知識が乏しいことも生命の定義を困難にしている<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Nealson |first1=K.H. |last2=Conrad |first2=P.G. |title=Life: past, present and future |journal={{仮リンク|フィロソフィカル・トランザクションズB|en|Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B|label=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B}} |volume=354 |issue=1392 |pages=1923–39 |date=December 1999 |pmid=10670014 |pmc=1692713 |doi=10.1098/rstb.1999.0532 |url=http://journals.royalsociety.org/content/7r10hqn3rp1g1vag/fulltext.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Bioethics">{{Cite journal2|last=Mautner |first=Michael N. |title=Life-centered ethics, and the human future in space |journal=Bioethics |volume=23 |pages=433–40 |date=2009 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00688.x |pmid=19077128 |url=http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFLifeCenteredBioethics2009Paper.pdf |issue=8 |url-status=live |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20121102064743/http://www.astro-ecology.com/PDFLifeCenteredBioethics2009Paper.pdf |archivedate=2 November 2012 }}</ref>。哲学における生命の定義も試みられているが、生命体と非生命体の区別においては生物学と似たような困難に直面している<ref name="Jeuken1975">{{Cite journal2|title=The biological and philosophical defitions of life |author=Jeuken M |journal=Acta Biotheoretica |volume=24 |issue=1–2 |pages=14–21 |date=1975 |doi=10.1007/BF01556737|pmid=811024 }}</ref>。また、生命を法的に定義することも広く議論されてきたものの、法学における論争は主に特定の人間の死亡を宣告する条件と死亡宣告の影響に集中している<ref name="Capron1978">{{Cite journal2|title=Legal definition of death |author=Capron AM |journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences |date=1978 |doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb50352.x |volume=315 |issue=1 |pages=349–62|bibcode=1978NYASA.315..349C }}</ref>。 |

|||

生命の定義について総意が得られないため、生物学における現在の定義のほとんどは記述的なものになっている。生命とは、与えられた環境においてその存在を維持、促進、または強化するものの特性であると考えられている。これは、次の特性のすべて、またはほとんどを意味する<ref name="McKay" /><ref name="Koshland">{{Cite journal |title=The Seven Pillars of Life |journal=Science |date=22 March 2002 | first=Daniel E. Jr. | last=Koshland |volume=295 |issue=5563 |pages=2215–2216 |doi=10.1126/science.1068489 |pmid=11910092 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language |publisher=Houghton Mifflin |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-618-70173-5 |edition=4th |chapter=life }}</ref><ref name="merriamwebster">{{cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/life|title=Life|publisher=Merriam-Webster Dictionary|access-date=25 July 2022|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211213211541/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/life|archive-date=13 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://phoenix.lpl.arizona.edu/mars141.php |title=Habitability and Biology: What are the Properties of Life? |access-date=6 June 2013 |website=Phoenix Mars Mission |publisher=The University of Arizona |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140416114923/http://phoenix.lpl.arizona.edu/mars141.php |archive-date=16 April 2014 }}</ref><ref name="JBS-2012Feb">{{cite journal |last=Trifonov |first=Edward N. |title=Definition of Life: Navigation through Uncertainties |journal=Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics |volume=29 |issue=4 |pages=647–650 |doi=10.1080/073911012010525017 |pmid=22208269 |date=2012 |s2cid=8616562 |doi-access=free }}</ref>。 |

|||

何が「生きているか」を考える難しさを示す実例に[[HeLa細胞]]が挙げられる事もある。これは[[ヘンリエッタ・ラックス]]というアメリカ人女性の子宮がん細胞を元にしたヒト細胞であり、培養され世界中の研究所に分配され試験に用いられている。ヘンリエッタ個人は既に亡くなったが、彼女由来の[[細胞]]は現在でも生きている。生命の基本的活動が細胞である事、そして「生きている」状態には明瞭な線引きができないさまざまな段階が存在すると考えられている<ref name="Oshima46">[[#大島(1994)|大島(1994)、p.46-50、第2章 宇宙の中の生命、(1)生命の三つの特徴]]</ref>。 |

|||

# [[恒常性]]:一定の状態を維持するための内部環境の調節。たとえば、体温を下げるための[[発汗]]など。 |

|||

== 生命観・生命論の歴史 == |

|||

# [[生命の階層|組織化]]:生命の基本単位である1つまたは複数の[[細胞]]から構造的に構成されていること。 |

|||

生命とは何か、ということについての論や見解を生命論や生命観と言う<ref name="iwanami">『岩波 生物学事典』【生命】</ref>。 |

|||

# [[代謝]]:化学物質を細胞成分に変換したり([[同化作用]])、有機物を分解したりするために([[異化作用]])使用されるエネルギーの変換。生物は恒常性の維持やその他の活動のために{{Ill2|生体エネルギー学|en|Bioenergetics|label=エネルギー}}を必要とする。 |

|||

# {{Ill2|細胞成長|en|Cell growth|label=成長}}:異化よりも同化の割合が高い状態を維持すること。成長する生物はサイズと構造が増大する。 |

|||

# [[適応 (生物学)|適応]]:生物がその[[生息地|生息環境]]でよりよく生きられるようになる進化の過程のこと<ref>{{cite book |last=Dobzhansky |first=Theodosius |author-link=Theodosius Dobzhansky |chapter=On Some Fundamental Concepts of Darwinian Biology |date=1968 |chapter-url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8094-8_1 |title=Evolutionary Biology |pages=1–34 |place=Boston, MA |publisher=Springer US |doi=10.1007/978-1-4684-8094-8_1 |isbn=978-1-4684-8096-2 |access-date=23 July 2022 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730033922/https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4684-8094-8_1 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Wang |first=Guanyu |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868928102 |title=Analysis of complex diseases : a mathematical perspective |date=2014 |isbn=978-1-4665-7223-2 |location=Boca Raton |oclc=868928102 |access-date=23 July 2022 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730033921/https://www.worldcat.org/title/analysis-of-complex-diseases-a-mathematical-perspective/oclc/868928102 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/906025831 |title=Climate change impact on livestock : adaptation and mitigation |date=2015 |editor-last1=Sejian |editor-first1=Veerasamy |editor-last2=Gaughan |editor-first2=John |editor-last3=Baumgard |editor-first3=Lance |editor-last4=Prasad |editor-first4=C. S. |isbn=978-81-322-2265-1 |location=New Delhi |oclc=906025831 |access-date=23 July 2022 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730033921/https://www.worldcat.org/title/climate-change-impact-on-livestock-adaptation-and-mitigation/oclc/906025831 |url-status=live }}</ref>。 |

|||

# {{Ill2|刺激 (物理学)|en|Stimulus (physiology)|label=刺激}}に対する反応:[[単細胞生物]]が外部の化学物質から遠ざかるときの収縮、[[多細胞生物]]のあらゆる感覚を伴う複雑な反応、あるいは植物の葉が太陽の方を向く運動([[屈光性]])、[[走化性]]など。 |

|||

# [[生殖]]:1つの親生物から[[無性生殖]]で、または2つの親生物から[[有性生殖]]で、新しい個体を生み出す能力のこと。 |

|||

=== 物理学 === |

|||

[[古代ギリシャ]]人たちは、生きている状態のことを{{lang-el-short|Ψυχή}} [[プシュケー]]と呼んでいた。プシュケーというのはもともとは[[息]]([[呼吸]])のことであり、呼吸は生きていることを示す最も目立つ特徴なので、この言葉が「生きていること= 生命」も指すようになり、転じて[[日本語]]の「[[心]]」や「[[霊魂]]」という概念まで意味するようになった。 |

|||

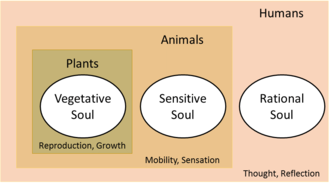

[[アリストテレス]]は Peri psyches 『[[霊魂論|ペリ・プシュケース]]』でこのプシュケーについて論じた。(同著の題名は直訳すれば『[[プシュケー]]について』である。)アリストテレスは初期段階では、生きものの種類によって異なるプシュケーの段階があると見なしていて、(1)植物的プシュケー (2)動物的プシュケー (3)理性的プシュケー(人間のプシュケー)というように区別していたが、やがて[[植物]]・[[動物]]・[[人間]]の間にプシュケーの差というのはさほど絶対的なものではないと見なすようになり、最終的にはそれらプシュケーに差はない、とも記した。 |

|||

{{further|{{ill2|エントロピーと生命|en|Entropy and life}}}} |

|||

{{seealso|生物学史}} |

|||

[[物理学]]の観点から見ると、生物は組織化された分子構造を持つ[[熱力学系]]であり、生存の必要に応じて自己複製し進化することができる<ref name="Luttermoser-1">{{cite web |last1=Luttermoser |first1=Donald G. |title=ASTR-1020: Astronomy II Course Lecture Notes Section XII |url=http://www.etsu.edu/physics/lutter/courses/astr1020/a1020chap12.pdf |publisher=[[:en:East Tennessee State University|East Tennessee State University]] |access-date=28 August 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120322185054/http://www.etsu.edu/physics/lutter/courses/astr1020/a1020chap12.pdf |archive-date=22 March 2012 }}</ref><ref name="Luttermoser-2">{{cite web |last1=Luttermoser |first1=Donald G. |title=Physics 2028: Great Ideas in Science: The Exobiology Module |url=http://www.etsu.edu/physics/lutter/courses/phys2028/p2028exobnotes.pdf |date=Spring 2008 |publisher=[[:en:East Tennessee State University|East Tennessee State University]] |access-date=28 August 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120322185041/http://www.etsu.edu/physics/lutter/courses/phys2028/p2028exobnotes.pdf |archive-date=22 March 2012 }}</ref>。また、[[熱力学]]的には、生命は周囲の勾配を利用してそれ自身の不完全なコピーを作り出す開放系と説明されている。これを別の言い方にすれば、生命を「[[ダーウィニズム|ダーウィン的進化]]を遂げることができる自立した化学系」と定義することもできる<ref name="Review 2009">{{cite journal |title=What makes a planet habitable? |journal=The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review |year=2009 |last1=Lammer |first1=H. |last2=Bredehöft |first2=J.H. |last3=Coustenis |first3=A. |author3-link=Athena Coustenis |last4=Khodachenko |first4=M.L. |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=181–249 |doi=10.1007/s00159-009-0019-z |url=http://veilnebula.jorgejohnson.me/uploads/3/5/8/7/3587678/lammer_et_al_2009_astron_astro_rev-4.pdf |access-date=3 May 2016 |quote=Life as we know it has been described as a (thermodynamically) open system (Prigogine et al. 1972), which makes use of gradients in its surroundings to create imperfect copies of itself. |coauthors=etal |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160602235333/http://veilnebula.jorgejohnson.me/uploads/3/5/8/7/3587678/lammer_et_al_2009_astron_astro_rev-4.pdf |archive-date=2 June 2016 |bibcode=2009A&ARv..17..181L|s2cid=123220355 }}</ref>。この定義は、[[カール・セーガン]]の提案に基づいて、[[宇宙生物学]]の目的のために生命を定義しようとする[[アメリカ航空宇宙局|NASA]]の委員会によって採用された<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Benner |first=Steven A. |date=December 2010 |title=Defining Life |journal=Astrobiology |volume=10 |issue=10 |pages=1021–1030 |doi=10.1089/ast.2010.0524 |pmc=3005285 |pmid=21162682 |bibcode=2010AsBio..10.1021B}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first1=Gerald F. |title=Extraterrestrials |last1=Joyce |author-link=Gerald Joyce |pages=139–151 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=1995 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511564970.017 |isbn=978-0-511-56497-0 |chapter=The RNA World: Life before DNA and Protein |hdl=2060/19980211165 |s2cid=83282463 }}</ref>。しかし、この定義によれば、単一の有性生殖個体はそれ自体で進化することができないため、生きているとは言えないとして、広く批判されている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Benner |first=Steven A. |date=December 2010 |title=Defining Life |journal=Astrobiology |volume=10 |issue=10 |pages=1021–1030 |doi=10.1089/ast.2010.0524 |pmc=3005285 |pmid=21162682|bibcode=2010AsBio..10.1021B }}</ref>。この潜在的な欠陥の理由は、「NASAの定義」が生命を生きた個体ではなく、現象としての生命に言及していることによる不完全さにある<ref name="Piast-2019">{{Cite journal |last=Piast |first=Radosław W. |date=June 2019 |title=Shannon's information, Bernal's biopoiesis and Bernoulli distribution as pillars for building a definition of life |journal=Journal of Theoretical Biology |volume=470 |pages=101–107 |doi=10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.03.009 |pmid=30876803 |bibcode=2019JThBi.470..101P |s2cid=80625250 }}</ref>。一方、現象としての生命と生きている個体としての生命という概念に基づく定義もあり、それぞれ自己維持可能な情報の[[連続体力学|連続体]]と、この連続体の別個の要素として提案されている。この考え方の大きな強みは、生物学的な{{Ruby|語彙|ごい}}を避け、数学と物理学の観点から生命を定義していることである<ref name="Piast-2019" />。 |

|||

また、「すべての物質は生きている」とする哲学的な考え方が古くから現代にいたるまである。古くは古代ギリシャの[[ミレトス学派]]にもそうした考え方があったことが知られている。こうした考え方を{{仮リンク|物活論|en|hylozoism}} hylozoism と言う。 |

|||

=== 生体系 === |

|||

ヨーロッパでは[[中世]]、[[キリスト教]]が広がり、[[旧約聖書]]の[[創世記]]の記述に従い、[[神]]が[[自然]]も[[人間]]も、動物・植物も、その他 生きとし生けるものすべてを造ったと考えていた。また、[[12世紀ルネサンス]]によって[[イスラーム]](アラビア語)の文献が[[ラテン語]]に翻訳されるようになると、そこで解説されていた[[アリストテレス]]の考え方が知られるようになり、その生命論も受け入れられるようになった。 |

|||

{{main|{{ill2|生体系|en|Living systems}}}} |

|||

[[1648年]]に[[ルネ・デカルト|デカルト]]が、''Le monde''(『世界論』とも『宇宙論』とも)の後半にあたるTraité de l'homme(『[[人間論 (デカルト)|人間論]]』)を出版した<ref name="rikai_chap2_23">[[山口裕之 (哲学者)|山口裕之]]『ひとは生命をどのように理解してきたか』講談社、2011年 p.80-113</ref>。デカルトは、人間も含めて全ての生物は神が制作した[[機械]]だと見なした<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。当時、ものの喩えではなく、[[宇宙]]は機械だと考えられたが、こうした考えの背景には「神が宇宙を制作した」というキリスト教の信仰がある<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。と同時に、その本でデカルトは、例えば[[心臓]]は[[熱機関]]だとし、[[運動]]によって説明できる、とし、(アリストテレスが用いていたプシュケーという概念の系統に属するともいえる)植物プシュケーや感覚プシュケーなどは用いなくても説明できる、とした<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" /><ref>『デカルト著作集4』p.286</ref>。アリストテレスが[[プシュケー]]を用いて、生命と非生命の区別をしふたつは異なっているとしたのに対し、デカルトはその差異は見せかけのものだとして、全てを物の運動で説明しようとした<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。デカルトの考え方は[[機械論]]と呼ばれる。 |

|||

[[分子化学]]に必ずしも依存しない{{ill2|生体系|en|Living systems|label=生体系理論}}({{Lang-en-short|living systems}})の視点に立つ人もいる。生命の体系的な定義の一つは、生物は[[自己組織化]]し、[[オートポイエーシス|オートポイエティック]](自己生産的)であるとするものである。これの変種として、[[スチュアート・カウフマン]]による『[[自律エージェント|自律的エージェント]]、または自己複製が可能で、少なくとも1つの[[熱力学サイクル|熱力学的作業サイクル]]を完了できる[[マルチエージェントシステム|マルチエージェント系]]』という定義もある<ref>{{Cite book |first1=Stuart |last1=Kaufmann |title=Science and Ultimate Reality |date=2004 |chapter=Autonomous agents |editor1-first=John D. |editor1-last=Barrow |editor2-last=Davies |editor3-first=C.L. |editor3-last=Harper, Jr. |pages=654–666 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511814990.032 |isbn=978-0-521-83113-0 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K_OfC0Pte_8C&pg=PA654 |editor2-first=P.C.W. |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=5 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231105190205/https://books.google.com/books?id=K_OfC0Pte_8C&pg=PA654#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref>。この定義は、時間の経過に伴う、新奇な機能の進化によって拡張されている<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Longo |first1=Giuseppe |last2=Montévil |first2=Maël |last3=Kauffman |first3=Stuart |title=Proceedings of the 14th annual conference companion on Genetic and evolutionary computation |chapter=No entailing laws, but enablement in the evolution of the biosphere |date=1 January 2012 |url=https://www.academia.edu/11720588 |series=GECCO '12 |pages=1379–1392 |doi=10.1145/2330784.2330946 |isbn=978-1-4503-1178-6 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170511103757/http://www.academia.edu/11720588/No_entailing_laws_but_enablement_in_the_evolution_of_the_biosphere |archive-date=11 May 2017 |arxiv=1201.2069 |citeseerx=10.1.1.701.3838 |bibcode=2012arXiv1201.2069L |s2cid=15609415 }}</ref>。 |

|||

[[18世紀]]になると、それを批判する動きが出た。18世紀[[フランス]]の哲学者[[エティエンヌ・ボノ・ドゥ・コンディヤック|コンディアック]]が[[1749年]]に『体系論』を出版したが、そこで彼はデカルト以来の17世紀的な「体系」は、事実に根拠を持たない想像力の産物だとして批判し、学問的な知識というのは、“[[ニュートン力学]]のように”観察にもとづく事実を出発点にして構築しなければいけない、と述べた<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。18世紀に博物学が再隆盛した理由としてジャック・ロジェは17世紀の内戦の時代の後に社会が全体的に安定し、人々が「退屈」したことを挙げた。退屈な現実から逃れるため、異国の文物や自然学研究に関心を持ったという<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。 |

|||

=== 死 === |

|||

18世紀には生命と物質の概念の区分けは現代人と異なっていた。たとえば、18世紀の[[博物学]]における分類体系においては、大抵は、「動物界」「植物界」「鉱物界」が並置されていた。分類学の父とされる[[リンネ]]の『自然の体系』(1735)はその典型で、冒頭で「自然物は鉱物界、植物界、動物界の三界に区分される。鉱物は成長する。植物は成長し、生きる。動物は成長し、生き、感覚を持つ」と定義された<ref name="rikai_64">『ひとは生命をどのように理解してきたか』p.64</ref>。 |

|||

{{main|死}} |

|||

すべての[[:en:creature|creature]](被造物。神が創造したもの)というのは、[[鉱物]]のような単純なものから植物、動物、そして[[人間]]のような複雑な存在へ、さらには人間よりも高度な[[天使]]へと連続的な序列をなしている、というイメージはヨーロッパでは根強いものがあった<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />(この連続的な階梯は「{{仮リンク|存在の大いなる連鎖|en|Great chain of being}} the great chain of being 」と呼ばれる)。 |

|||

[[File:Male Lion and Cub Chitwa South Africa Luca Galuzzi 2004.JPG|right|thumb|この[[アフリカスイギュウ]]のように、動物の死体は[[生態系]]によって再利用され、生きている生物にエネルギーと栄養素を供給する。]] |

|||

リンネと同年生まれの[[ビュフォン|ビュッフォン]]は自著『博物誌』においてリンネの分類体系(花のおしべやめしべの数で分類するもの)を批判しつつ、客観的な分類は不可能だ、と主張した。上述のように全ての被造物は連続的な序列をなしていると考えられていたので、連続的に変化するものに客観的な区分線などないのだから、自然を分類するということは人為的あるいは恣意的だ、とした<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。ビュッフォンの『博物誌』もまた四足獣類、鳥類、鉱物の巻があり、それらを等しく対象としていた。 |

|||

[[死]]とは、生物または細胞におけるすべての生体機能や生命現象が停止することである<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Definition of death |url=http://encarta.msn.com/dictionary_1861602899/death.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091103065510/http://encarta.msn.com/dictionary_1861602899/death.html |archive-date=3 November 2009 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="define_death">{{cite web |title=Definition of death |website=Encyclopedia of Death and Dying |publisher=Advameg, Inc. |url=http://www.deathreference.com/Da-Em/Definitions-of-Death.html |access-date=25 May 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070203141750/http://www.deathreference.com/Da-Em/Definitions-of-Death.html |archive-date=3 February 2007 }}</ref>。死を定義する上での課題の一つに死と生の区別があげられる。死とは、生命が終わる瞬間、あるいは生命に続く状態が始まる時のどちらかを指すと考えられる<ref name="define_death" />。しかし、生命機能の停止は臓器系をまたいで同時に起こることは少なく、いつ死が起こったかを判断するのは困難である<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Crossing Over: How Science Is Redefining Life and Death |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/04/dying-death-brain-dead-body-consciousness-science/ |author=Henig, Robin Marantz |author-link=Robin Marantz Henig |magazine=[[:en:National Geographic (magazine)|National Geographic]] |date=April 2016 |access-date=23 October 2017 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171101071129/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/04/dying-death-brain-dead-body-consciousness-science/ |archive-date=1 November 2017 }}</ref>。そのため、こうした決定には、生と死の間に概念的な境界線を引く必要がある。生命をどのように定義するかについての総意はほとんどないことから、これは未解決の問題である。何千年もの間、死の本質は世界の宗教的伝統や哲学的探求の中心的な関心事であった。多くの宗教では、[[死後]]の世界や[[魂]]の[[生まれ変わり|転生]]、あるいは後日の肉体の{{Ill2|復活|en|Resurrection|label=復活|preserve=1}}を信仰している<ref>{{Cite web|title=How the Major Religions View the Afterlife|url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/how-major-religions-view-afterlife|access-date=4 February 2022|website=Encyclopedia.com|archive-date=4 February 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220204201436/https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/how-major-religions-view-afterlife|url-status=live}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[ジャン=バティスト・ラマルク|ラマルク]]は[[1809年]]の著書『[[動物哲学]]』において、「動植物と鉱物の間には越えられない断絶がある」と強調した。これは18世紀に台頭したVitalism([[生気論|ヴァイタリズム]])という考え方が背景にある<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。ヴァイタリズムというのは「生きているものには、物質とは異なる特殊な生命[[原理]]がはたらいている」とする考え方であり<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />、「生命原理」「生命特性」や「生命力」といった用語が用いられた<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。この「生命原理」は、個体全体にはたらくというよりも、個体を構成する器官や組織が持つ特性で、何らかの[[自然法則]]である、と考えられた<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。こうした2点でヴァイタリズムは単なるアニミズムとは異なっていた。アニミズムが「ただの物体としての身体に、超自然的・非物質的な、だが実体的なアニマが宿る」と考えるのに対して、ヴァイタリズムというのは「身体を構成する組織や物質そのものが、何らかの生命原理を持っている。その原理は自然法則であって研究できる」と考える<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。17世紀〜18世紀にかけて解剖実験が行われるようになり、切り離された心臓がしばらく鼓動しつづけることや、切り離された筋肉が刺激によって動くことが観察されたことなどから、器官や組織は生きている、とする考え方が生まれた<ref name="rikai_chap2_23" />。 |

|||

=== 「生命の縁」ウイルス === |

|||

20世紀になると[[全体論|ホーリスム]]的な考え方も提唱され、また[[生気論|ネオヴァイタリズム]]や[[有機体論]]なども登場した<ref name="iwanami"/>。 |

|||

{{main|ウイルス}} |

|||

現在では、生命は自動制御の機械に譬えられることも多いが<ref name="iwanami"/>、同時にそれは有機体論的にも把握されており、[[分子生物学]]な見解も認められており、また、生命を可能ならしめている土台には[[情報]]の伝達<ref name="iwanami"/>や[[エネルギー]]の方向性のある変換がある<ref name="iwanami"/>、とも言われるなど様々な切り口で把握されており、現代の生命論は複雑な様相を呈している。 |

|||

[[File:Adenovirus transmission electron micrograph B82-0142 lores.jpg|thumb|right|[[透過型電子顕微鏡]]で見た[[アデノウイルス]]]] |

|||

== 宗教における生命 == |

|||

[[Image:Tree of Life, Medieval.jpg|thumb|right|120px|[[カバラ]]に記されている[[生命の樹 (旧約聖書)|生命の樹]]]] |

|||

多くの宗教においては、[[死後の世界]]もしくは、[[輪廻]]、[[転生]]などがあると考えられている。この場合、人間の主体、存在の本質、あるいは人格そのものを、魂、[[霊魂]]と呼ぶ。生命と霊魂を同一視するかどうかは、様々である。 |

|||

ウイルスが生きていると見なすべきかどうかは議論の分かれるところである<ref>{{Cite web |title=Virus |url=https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Virus |access-date=25 July 2022 |website=Genome.gov |archive-date=11 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220511064713/https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Virus |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Are Viruses Alive? |url=https://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/yellowstone/viruslive.html |access-date=25 July 2022 |website=Yellowstone Thermal Viruses |archive-date=14 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220614031640/https://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/yellowstone/viruslive.html |url-status=live }}</ref>。ウイルスは生命の形態というよりも、{{Ill2|コーディング領域|en|Coding region|label=遺伝子をコード|preserve=1}}する[[DNA複製|複製装置]]に過ぎないと見なされることも多い<ref>{{cite journal |title=Are viruses alive? The replicator paradigm sheds decisive light on an old but misguided question |journal=Studies in the History and Philosophy of Biology and Biomedical Science |volume=59 |pages=125–134 |date=7 March 2016 |last1=Koonin |first1=E.V. |last2=Starokadomskyy |first2=P. |doi=10.1016/j.shpsc.2016.02.016 |pmid=26965225 |pmc=5406846}}</ref>。ウイルスは[[遺伝子]]を持ち、自然選択によって進化し<ref name="pmid17914905">{{Cite journal |last1=Holmes |first1=E.C. |title=Viral evolution in the genomic age |journal=PLOS Biol. |volume=5 |issue=10 |page=e278 |date=October 2007 |pmid=17914905 |pmc=1994994 |doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0050278 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Forterre 2010">{{cite journal |title=Defining Life: The Virus Viewpoint |journal=Orig Life Evol Biosph |date=3 March 2010 |first=Patrick |last=Forterre |volume=40 |issue=2 |pages=151–160 |doi=10.1007/s11084-010-9194-1 |bibcode=2010OLEB...40..151F |pmc=2837877 |pmid=20198436}}</ref>、自己組織化によって自分自身のコピーを複数作成することで複製することから、「生命の縁にいる生物」と表現されている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rybicki |first=EP |date=1990 |url=https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA00382353_6229 |title=The classification of organisms at the edge of life, or problems with virus systematics |journal=S Afr J Sci |volume=86 |pages=182–186 |access-date=5 November 2023 |archive-date=21 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210921114412/https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA00382353_6229 |url-status=live }}</ref>。しかし、ウイルスは代謝しないため、新しい[[代謝産物|産物]]を作るには宿主細胞が必要である。宿主細胞内でのウイルスの自己組織化は、生命が自己組織化した[[有機分子]]として始まったという仮説を裏付ける可能性があるため、[[生命の起源]]を研究する上で重要な意味を持つ<ref name="pmid16984643">{{Cite journal |last1=Koonin |first1=E.V. |author1-link=Eugene Koonin |last2=Senkevich |first2=T.G. |last3=Dolja |first3=V.V. |title=The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells |journal=Biology Direct |volume=1 |page=29 |date=2006 |pmid=16984643 |pmc=1594570 |doi=10.1186/1745-6150-1-29 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/tutorial/virorig.html#Virus%20Origins |title=Origins of Viruses |last=Rybicki |first=Ed |date=November 1997 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090509094459/http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/tutorial/virorig.html|archive-date=9 May 2009 |url-status=dead |access-date=12 April 2009}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[古代インド]]の[[ヴェーダ]]や[[仏教]]では、人間の命と動物の命は同列的に扱われていた。仏教では、人間が動物に転生する考えなども見られるし、宗教家が動物を食べることはあまりよくないとする例もある。また[[ジャイナ教]]では、虫を踏み潰して無駄な殺生をすることがないよう、僧侶は常に[[箒|ほうき]]を持ち歩くという習慣も見ることができる。 |

|||

== 研究の歴史 == |

|||

一方、[[キリスト教]]では、人間と動物の生命は全く別のものとする傾向が強く、人間という存在は「[[神]]によって[[命]]を吹き込まれたもの」であり特別な存在である。さらに言えば、「命を失った者」と背信者を呼ぶ比喩が存在し、「命を得た者」「[[永遠の命]]を得た者」と神を信じるようになった者、[[天国]]に至る権利を得た者を呼ぶ場合がある。 |

|||

{{節スタブ}} |

|||

== |

=== 唯物論 === |

||

[[ファイル:Soybeanvarieties.jpg|right|120px|thumb|[[種子]]([[大豆]])]] |

|||

[[File:Sunflower seedlings.jpg|thumb|left|120px|[[発芽]]した[[ひまわり]]]] |

|||

[[ファイル:Bifidobacterium adolescentis Gram.jpg|thumb|left|120px|[[ビフィズス菌]]]] |

|||

生物学では、生物の示す固有の現象を生命現象と呼ぶ。生命とは、その根元にあるものとの思想があり、生気論もその一つである。 |

|||

{{main|唯物論}} |

|||

生命現象には様々な側面があるが、一般に生物学では、根本的な生命の定義に関わる部分は、その内部での物質交換と外部との物質のやりとり、および同じ型の[[個体]]の再生産にあると考えられている。また、そのような性質を持つ最小の単位が[[細胞]]であるので、細胞を生命の最小の単位と見なし、それから構成されるものに生命を認める、というのが一般的である<ref name="Oshima46" />。植物の[[種子]]などのように、著しく代謝活動が不活発な状態でも代謝活動の再開が見込める場合には生きている、と呼ぶ。 |

|||

初期の生命に関する理論の中には、存在するものはすべて物質であり、生命は物質の複雑な形態や配列に過ぎないという唯物論的なものがある。[[エンペドクレス]](紀元前430年)は、宇宙に存在するすべてのものは、土、水、空気、火という永遠の「[[四元素|四つの元素]]」または「万物の根源」の組み合わせでできていると主張した。すべての変化は、これらの4つの元素の配置と再配置によって説明される。生命のさまざまな形態は、元素の適切な混合によって引き起こされる<ref>{{cite web |first1=Richard |last1=Parry |date=4 March 2005 |title=Empedocles |website=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/empedocles/ |access-date=25 May 2012 |archive-date=13 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120513201301/http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/empedocles/ |url-status=live }}</ref>。[[デモクリトス]](紀元前460年)は[[原子論|原子論者]]であり、生命の本質的な特徴は「[[魂]]([[プシュケー]])」を持つことであり、魂は他のすべてのものと同様に、火のような原子から構成されていると考えた。彼は、生命と熱の間に明らかな関係があり、火が動くことから、火について詳しく説明した<ref name="democritus">{{cite web |first1=Richard |last1=Parry |date=25 August 2010 |title=Democritus |website=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/democritus/#4 |access-date=25 May 2012 |archive-date=30 August 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060830030642/http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/democritus/#4 |url-status=live }}</ref>。これに対して[[プラトン]]は、世界は不完全に物質に反映された永続的な「[[イデア論|形]]([[イデア]])」によって組織されていると考え、「形」は方向性や知性を与え、世界で観察される規則性を説明すると主張した<ref>{{cite book |title=Cause and Explanation in Ancient Greek Thought |last=Hankinson |first=R.J. |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1997 |isbn=978-0-19-924656-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iwfy-n5IWL8C |page=125 |df=dmy-all |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194747/https://books.google.com/books?id=iwfy-n5IWL8C |url-status=live }}</ref>。[[古代ギリシア|古代ギリシャ]]に端を発した機械論唯物論([[機械論]])は、フランスの哲学者[[ルネ・デカルト]](1596-1650)によって復活して修正され、彼は動物や人間は共に機械として機能する部品の集合体であると主張した。この考えは、[[ジュリアン・オフレ・ド・ラ・メトリー]](1709-1750)の著書『''L'Homme Machine''(人間機械論)』の中でさらに発展することとなった<ref>{{cite book |last=de la Mettrie |first=J.J.O. |date=1748 |title=L'Homme Machine |trans-title=Man a machine |publisher=Elie Luzac |place=Leyden }}</ref>。19世紀には、生物学における[[細胞説|細胞理論]]の進歩がこの考え方を後押しした。[[チャールズ・ダーウィン]]の[[進化論]](1859年)は、[[自然選択説|自然選択]]による種の起源について[[機械論]]的に説明したものである<ref>{{cite book |first1=Paul |last1=Thagard |title=The Cognitive Science of Science: Explanation, Discovery, and Conceptual Change |publisher=MIT Press |date=2012 |isbn=978-0-262-01728-2 |pages=204–205 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HrJIV19_nZYC&pg=PA204 |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194751/https://books.google.com/books?id=HrJIV19_nZYC&pg=PA204 |url-status=live }}</ref>。20世紀初頭、{{Ill2|ステファン・ルデュック|en|Stéphane Leduc}}(Stéphane Leduc)(1853-1939)は、生物学的な過程は物理学と化学の観点から理解することができ、その成長はケイ酸ナトリウム溶液に浸した[[ケミカルガーデン|無機結晶の成長]]に似ているという考えを推進した。彼の著書『''La biologie synthétique''(合成生物学)』<ref>{{cite book |last=Leduc |first=Stéphane |author-link=Stéphane Leduc |date=1912 |title=La Biologie Synthétique |trans-title =Synthetic Biology |publisher=Poinat |place =Paris}}</ref>で述べられた彼の考えは、存命中はほとんど否定されていたものの、後年のラッセルやバルジらの研究によって再び関心を集めるようになった<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1089/ast.2013.1110 |title=The Drive to Life on Wet and Icy Worlds|year=2014|last1=Russell |first1=Michael J. |last2=Barge |first2=Laura M. |last3=Bhartia |first3=Rohit |last4=Bocanegra |first4=Dylan |last5=Bracher |first5=Paul J. |last6=Branscomb |first6=Elbert |last7=Kidd |first7=Richard |last8=McGlynn |first8=Shawn |last9=Meier |first9=David H. |last10=Nitschke |first10=Wolfgang |last11=Shibuya |first11=Takazo |last12=Vance |first12=Steve |last13=White |first13=Lauren |last14=Kanik |first14=Isik |display-authors=3 |journal=Astrobiology |volume=14 |issue=4 |pages=308–343 |pmid=24697642 |pmc=3995032 |bibcode=2014AsBio..14..308R}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[ファイル:Nucleocapsids.png|thumb|200px|right|(左)正二十面体様 (中)らせん構造 (右)無人探査機のような形状の[[ファージ]]]] |

|||

ところが、[[ウイルス]]や[[ウイロイド]]などの存在は判断が難しい。ウイルスを生物とするか無生物とするかについて長らく論争があり、いまだに決着していないと言ってもよい<ref name="fukuoka2">{{Cite book|和書|author=福岡伸一|year=2007|title=生物と無生物のあいだ|publisher=講談社|chapter=第2章|pages=29-46}}</ref>。 |

|||

=== 質料形相論 === |

|||

ウイルスは増殖はするが代謝を行っていない<ref name="fukuoka2" />。増殖について言えば、宿主となる生物が持つ有機物質合成機能のシステムの中にウイルスが入り込むと、宿主のシステムが言わば誤動作を起こしてしまいウイルスを増産してしまう。形状について言えば、ウイルスはDNAやRNAなどの[[核酸]]とそれを包む殻から成っている。概して幾何学的な形状を持っており、あるものは正二十面体のような多角立方体、あるものは無人火星探査機のようなメカニカルな形状をしており、同一種はまったく同形で、生物全般に見られる個体の多様性が見られない<ref name="fukuoka2" />。代謝について言えば、ウイルスは[[栄養]]を摂取することがなく、[[呼吸]]もしないし、[[老廃物]]の排泄もしておらず、つまり生命の特徴である[[代謝]]を一切行っていない<ref name="fukuoka2" />。また1935年にはすでに[[タバコモザイクウイルス]]の結晶化が成功している。結晶というのは、同じ構造を持つ単位が規則正しく充填される<ref name="fukuoka2" />。この点でもウイルスは生物というよりは物質と言える側面があることがわかった<ref name="fukuoka2" />。これらの相違点があるので普通はウイルスを生物とは認めない。 |

|||

また、ウイロイドというのは、寄生性RNAのことで、ウイルス同様に宿主内のシステムが異常なものであることを判別できずに増産してしまう等々の特徴はウイルス同様であり一般に生物とは認めない。 |

|||

ただし、これらも自己複製という点だけに着眼すれば単なる物質から一線を画しており、「ウイルスは生物と無生物の間をたゆたう何者かである<ref name="fukuoka2" />」とも福岡伸一は表現した。 |

|||

{{Main|{{ill2|質料形相論|en|Hylomorphism|preserve=1}}}} |

|||

近年の生命の定義の試みは多数あり主要なものを挙げただけでも相当な数になるが、参考までにその一例を紹介すると、例えば[[福岡伸一]]は、[[ルドルフ・シェーンハイマー]]の発見した「生命の動的状態」という概念を拡張し、'''[[動的平衡]]'''という概念を提示し、「生命とは[[動的平衡]]にある[[流れ]]である」とした<ref name="fukuoka9-15">{{Cite book|和書|author=福岡伸一|year=2007|title=生物と無生物のあいだ|publisher=講談社|chapter=第9-第15章|pages=152-272}}</ref>。 |

|||

生物は'''動的に'''平衡状態を作り出している<ref name="fukuoka9-15" />。生物というのは平衡が崩れると、その事態に対して[[反応]]を起こす<ref name="fukuoka9-15" />。そして福岡は、[[ノックアウトマウス]]の実験結果なども踏まえて、従来の生命の定義の設問は[[時間]]を見落としている、とし<ref name="fukuoka9-15" />、生命を機械に譬えるのは無理があるとする<ref name="fukuoka9-15" />。機械には時間が無く原理的にはどの部分から作ることもでき部品を抜き取ったり交換したりすることもでき生物に見られる一回性というものが欠如しているが、生物には不可逆的な時間の流れがあり、その流れに沿って折りたたまれ、二度と解くことのできないものとして存在している、とした<ref name="fukuoka9-15" />。 |

|||

[[File:Aristotelian Soul.png|thumb|upright=1.5|[[アリストテレス]]による、植物、動物、人間の魂の階層構造{{Enlink|Soul#Aristotle|Soul#Aristotle|en}}。]] |

|||

{{seealso|生物}} |

|||

質料形相論は、ギリシャの哲学者[[アリストテレス]](紀元前322年)によって最初に定式化された理論である。質料形相論の生物学への応用はアリストテレスにとって重要であり、現存する彼の著作では{{Ill2|アリストテレスの生物学|en|Aristotle's biology|label=生物学が広く論じられている}}。この見解では、物質的宇宙に存在するすべてのものは物質と「形」の両方を持っており、生物の「形」はその[[魂]](ギリシャ語の[[プシュケー]]、ラテン語の[[アニマ]])であるという。魂には次の3種類がある。植物の植物的魂(''vegetative soul'')は、植物を成長させ、腐敗させ、栄養を与えるが、運動や感覚を引き起こさない。動物的魂(''animal soul'')は、動物に動きと感覚を与える。そして、理知的魂(''rational soul'')は意識と理性の源であり、アリストテレスは人間だけにあると考えた<ref>{{Cite book |title=On the Soul |last=Aristotle |pages=Book II |no-pp=y |title-link=On the Soul }}</ref>。それぞれの高次の魂は、低次の魂のすべての性質を備えている。アリストテレスは、物質は「形」がなくても存在できるが、「形」は物質なしでは存在できず、したがって魂は肉体なしでは存在できないと考えた<ref>{{cite book |first1=Don |last1=Marietta |page=104 |title=Introduction to ancient philosophy |publisher=M.E. Sharpe |date=1998 |isbn=978-0-7656-0216-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Gz-8PsrT32AC |access-date=25 August 2020 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194754/https://books.google.com/books?id=Gz-8PsrT32AC |url-status=live }}</ref>。 |

|||

<gallery style="font-size:0.8em;"> |

|||

File:Megaptera novaeangliae -Bar Harbor, Maine, USA-8d.jpg|ジャンプする[[鯨]] |

|||

File:Formation flight.jpg|[[鳥]]の[[群れ]] |

|||

File:Blue Linckia Starfish.JPG|[[グレート・バリア・リーフ]]の[[さんご礁]]、[[アオヒトデ]]、[[魚]] |

|||

File:Biogradska suma.jpg|[[モンテネグロ]]の[[森林]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

この説明は、目的あるいは目標指向性という観点から現象を説明する{{Ill2|生物学におけるテレオロジー|en|Teleology in biology|label=生命の目的論的説明}}と矛盾しない。たとえば、ホッキョクグマの毛皮の白さは、カモフラージュ(偽装)という目的によって説明される。因果関係の方向(未来から過去へ)は、結果を事前原因という観点から説明する自然選択の科学的証拠と矛盾する。生物学的特徴は、将来の最適な結果を見ることで説明されるのではなく、問題の特徴の自然選択につながった種の過去の{{Ill2|生命の歴史|en|History of life|label=進化の歴史}}を見ることによって説明される<ref name="stewert_williams2010">{{Cite book |first1=Steve |last1=Stewart-Williams |date=2010 |title=Darwin, God and the meaning of life: how evolutionary theory undermines everything you thought you knew of life |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-76278-6 |pages=193–194 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KBp69los_-oC&pg=PA193 |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194752/https://books.google.com/books?id=KBp69los_-oC&pg=PA193 |url-status=live }}</ref>。 |

|||

== 生物物理学における生命 == |

|||

物理学者の[[エルヴィン・シュレーディンガー|シュレーディンガー]]は、著書『生命とは何か?』の中で生命を、ネゲントロピー(負のエントロピー)を取り入れ体内のエントロピーの増大を相殺することで定常状態を保持している開放定常系とした<ref>{{Cite book|和書|others=[[岡小天]]・[[鎮目恭夫]]共訳|year=1951|title=生命とは何か 物理学者のみた生細胞|series=岩波新書 第72|publisher=岩波書店}}</ref>。 |

|||

{{節スタブ}} |

|||

== 生 |

=== 自然発生 === |

||

{{Main|生命の起源}} |

|||

{{Seealso|創造論|創造科学}} |

|||

{{Main|自然発生説}} |

|||

地球上の生命は、およそ37億年前には存在していたという証拠がある<ref>"[http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/exhibits/historyoflife.php History of life through time]". University of California Museum of Paleontology.</ref><ref>新しい生物学 p.269</ref>。また、細胞を基本の構成単位としていること、核酸・タンパク質・脂質などからなることなどから、地球上の生命は全て単一の祖先から[[進化]]したか、他の生命は発生しなかった、ないしは発生してもすぐに絶滅したと考えられている。 |

|||

[[自然発生説|自然発生]]とは、生物は類似の生物からの系統を経ずに形成されるという考え方であった。典型的には、ノミのような特定の種の形態が、塵のような無生物から発生したり、あるいはネズミや昆虫が泥やゴミから季節的に発生するという考えであった<ref>{{Cite book |title=Origines Sacrae |last=Stillingfleet |first=Edward |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1697 }}</ref>。 |

|||

また、地球生命の起源を地球外部に求める説も存在する。1908年に[[スウェーデン]]の[[スヴァンテ・アレニウス]]が提唱したことに始まる[[パンスペルミア説]](胚種普遍説)は、細胞や生命の種が宇宙から飛来する場合に長期間受けるであろう有害な宇宙線を例にした否定論も多く、賛否入り混じったさまざまな議論が行われた<ref name="Oshima14" /><ref>「生命の起源 宇宙・地球における化学進化」p6-p7 小林憲正 講談社 2013年5月20日第1刷発行</ref>。その一方で、生命の材料たりえる[[有機化合物]]が宇宙空間に存在する証拠は数多く積み上がっている。隕石中からは、古くは1806年のアライス隕石から発見されている。本格的な研究は20世紀中ごろから始まり、アミノ酸・[[核酸塩基]]・炭化水素・ポリフィリンなどの発見が相次いだ<ref name="Oshima160">[[#大島(1994)|大島(1994)、p.160-171、第5章 地球外生命の可能性、(1)隕石‐太陽系の古文書]]</ref>。1986年3月に[[ハレー彗星]]が地球に近づいた際、[[日本]]・[[ヨーロッパ]]・[[ソ連]]は計5基の観測器を送り込み、様々な分析を行った。その結果、アミノ酸合成の中間物にあたる[[シアン化水素]]や[[ホルムアルデヒド]]、酸化炭素・炭化水素・アンモニア・硫化水素や硫化炭素・ヒドラジンなどが発見された。彗星は、太陽系形成初期の物質を維持していると考えられ、これが海を形成した後の地球に降ったならば、彗星から生命の材料たる有機化合物が供給された可能性がある。また、地球以外の天体にも同様に材料を分け与え、条件がそろえば生命が発生したことを否定できない<ref name="Oshima160"/>。[[電波天文学]]の発展が明らかにした星間物質の組成には、多様な有機化合物が発見されている。このような結果から、生命の素材を地球内部の化学合成だけに限定する必然性は段々と薄れつつある<ref name="Oshima160" />。 |

|||

自然発生説は[[アリストテレス]]によって提唱された<ref>{{cite book |author=André Brack |editor=André Brack |title=The Molecular Origins of Life |access-date=7 January 2009 |year=1998 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-56475-5 |page=[https://archive.org/details/molecularorigins0000brac/page/1 1] |chapter=Introduction |chapter-url=http://assets.cambridge.org/97805215/64755/excerpt/9780521564755_excerpt.pdf |url=https://archive.org/details/molecularorigins0000brac/page/1 }}</ref>。アリストテレスは、それ以前の自然哲学者の著作や、生物の外観に関する古代のさまざまな説明を統合し、発展させた。この説は2千年にわたって最良の説明と考えられていた。しかしこの考えは、[[フランチェスコ・レディ]]などの先人の研究を発展させた、1859年の[[ルイ・パスツール]]の実験によって決定的に覆された<ref>{{cite web |last1=Levine |first1=Russell |last2=Evers |first2=Chris |title=The Slow Death of Spontaneous Generation (1668–1859) |url=http://www.ncsu.edu/project/bio183de/Black/cellintro/cellintro_reading/Spontaneous_Generation.html |website=North Carolina State University |publisher=National Health Museum |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151009044415/http://www.ncsu.edu/project/bio183de/Black/cellintro/cellintro_reading/Spontaneous_Generation.html |archive-date=9 October 2015 |access-date=6 February 2016 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Fragments of Science |last=Tyndall |first=John |publisher=P.F. Collier |year=1905 |volume=2 |location=New York |pages=Chapters IV, XII, and XIII |no-pp=y }}</ref>。自然発生説という伝統的な考え方の否定は、生物学者の間ではもはや議論の余地はない<ref name="Bernal 1967">{{cite book |last=Bernal |first=J.D. |year=1967 |orig-year=Reprinted work by [[:en:Alexander Oparin|A.I. Oparin]] originally published 1924; Moscow: [[:en:Publishing houses in the Soviet Union|The Moscow Worker]] |title=The Origin of Life |url=https://archive.org/details/originoflife0000bern |url-access=registration |series=The Weidenfeld and Nicolson Natural History |others=Translation of Oparin by Ann Synge |location=London |publisher=[[:en:Weidenfeld & Nicolson|Weidenfeld & Nicolson]] |lccn=67098482}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Origins of Life: On Earth and in the Cosmos |last=Zubay |first=Geoffrey |publisher=Academic Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-12-781910-5 |edition=2nd }}</ref><ref name="Szathmary">{{cite book |author1=Smith, John Maynard |author2=Szathmary, Eors |title=The Major Transitions in Evolution |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford Oxfordshire |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-19-850294-4}}</ref>。 |

|||

== 典型的な生命現象 == |

|||

=== 自己複製 === |

|||

{{Main|生殖}} |

|||

生命の特徴のひとつに、自己と同じ子孫を複製し増殖する能力を持つことがある。これは核酸で構成される遺伝子を用いて行われる。地球生命の場合、4種類の塩基をD-リボース(またはD-デオキシリボース)という[[糖]]と結びついた化合物ヌクレオシドが、リン酸と結合してヌクレオチドとなり、これが鎖状につながって構成される。この各塩基には「塩基対」という水素結合で結びつきやすい組み合わせがあり、核酸は必ずこの塩基対に応じたもう1本の核酸と対をつくる。これが[[DNA]]である。対になったDNAを引き離すと、それぞれの核酸は周囲から塩基を集め、対の相手を作り、その結果同じDNAが2組出来上がる。これが生命の自己複製の基礎である<ref name="Oshima60">[[#大島(1994)|大島(1994)、p.60-66、第2章 宇宙のなかの生命、(3)特徴の2自己を複製する]]</ref>。 |

|||

=== 生気論 === |

|||

地球生命では、DNAの連なる塩基3つを1組とする意味を持ち、細胞を構成するたんぱく質のアミノ酸がどのように並ぶかを、DNAから複製したm-RNAで規定し、親と同じ構造を作り出す。生命が自己複製を行うにおいて、地球外の生命でも基本的に塩基対構造と似た働きを持つ物質を介すると考えられるが、地球環境内では塩基以外に相応する物質はほとんど無い。ただし、地球外生物では使用する塩基の数が4種以外であったり、生体の基本物質を規定する塩基数は3つ1組以外の組み合わせを利用する可能性も想定できる<ref name="Oshima60" />。 |

|||

{{Main|生気論}} |

|||

=== エネルギー代謝 === |

|||

{{Main|代謝}} |

|||

生命は、成長や増殖に必要な[[エネルギー]]源を外部から[[栄養]]の形で得る。栄養はそのまま用いることができないため、複雑な[[化学反応]]をへてエネルギーに変換するが、これを代謝という。 |

|||

生気論(バイタリズム)とは、非物質的な生命原理が存在するという信念である。これは[[ゲオルク・エルンスト・シュタール]](17世紀)に端を発し、19世紀半ばまで流行した<ref>{{cite book |first1=Sanford |last1=Schwartz |title=C.S. Lewis on the Final Frontier: Science and the Supernatural in the Space Trilogy |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-988839-9 |page=56 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4hQLdPtJe9EC&pg=PA56 |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194800/https://books.google.com/books?id=4hQLdPtJe9EC&pg=PA56 |url-status=live }}</ref>。そして、[[アンリ・ベルクソン]]、[[フリードリヒ・ニーチェ]]、[[ヴィルヘルム・ディルタイ]]などの哲学者、[[マリー・フランソワ・グザヴィエ・ビシャ|グザヴィエ・ビシャ]]のような解剖学者、[[ユストゥス・フォン・リービッヒ]]などの化学者たちの支持を受けた<ref name="Wilkinson">{{cite journal |first1=Ian |last1=Wilkinson |title=History of Clinical Chemistry – Wöhler & the Birth of Clinical Chemistry |journal=The Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine |volume=13 |issue=4 |date=1998 |url=http://www.ifcc.org/ifccfiles/docs/130304003.pdf |access-date=27 December 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160105031229/http://www.ifcc.org/ifccfiles/docs/130304003.pdf |archive-date=5 January 2016 }}</ref>。生気論には、{{Ill2|有機物|en|Organic matter|label=有機物|preserve=1}}と無機物の間には本質的な違いが存在するという考えや、有機物は生物からのみ作られるという信念が含まれていた。この考え方は、1828年、[[フリードリヒ・ヴェーラー]]が無機物から[[尿素]]を合成したことで否定された<ref>{{cite journal |title=Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs |author=Friedrich Wöhler |journal=[[:en:Annalen der Physik und Chemie|Annalen der Physik und Chemie]] |volume=88 |issue=2 |pages=253–256 |date=1828 |doi=10.1002/andp.18280880206 |url=http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15097k/f261.chemindefer |bibcode=1828AnP....88..253W |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120110094705/http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15097k/f261.chemindefer |archive-date=10 January 2012 |author-link=Friedrich Wöhler }}</ref>。この[[ヴェーラー合成]]は現代[[有機化学]]の出発点と考えられている。[[有機化合物]]が初めて[[無機化合物|無機反応]]によって生成された、歴史的にも意義のあることであった<ref name="Wilkinson" />。 |

|||

=== 死 === |

|||

{{Main|死}} |

|||

生物の細胞や臓器における生命活動が不可逆的に失なわれることを'''死'''と呼ぶ<ref>{{cite web2|title=Definition of death.|url=http://encarta.msn.com/dictionary_1861602899/death.html|work= |

|||

|archiveurl=https://webcitation.org/5kwsdvU8f|archivedate=2009-10-31|url-status=dead|accessdate=2010-04-30}}</ref><ref>[http://www.deathreference.com/Da-Em/Definitions-of-Death.html Defining of death.]</ref>。生命を定義することが難しいのと同様に、死を定義することも困難な問題である。そのため、生きている状態と死んでいる状態をはっきりと区別することはできない。多細胞生物においては、個体の死と細胞の死は別々に考えられるべきで、例えば、[[移植 (医療)|臓器移植]]の場合、臓器提供者が死んだとしても、移植が成功すればその臓器は生きていると考えられる。また生命体は普通、子をなしてその血統を存続させる。これを[[細胞]]レベルで見れば、細胞の分裂と融合に基づく連続性は常に維持されているため、その意味で生命は停止せずに連続していると表現する事も出来る。これを[[生命の連続性]]という。 |

|||

1850年代、[[ヘルマン・フォン・ヘルムホルツ]]は、[[ユリウス・ロベルト・フォン・マイヤー]]によって予想された筋肉運動ではエネルギーが失われないことを実証し、筋肉を動かすのに必要な「生命力({{Lang-en-short|vital forces}})」が存在しないことを示唆した<ref>{{cite book |first1=Anson |last1=Rabinbach |title=The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity |publisher=University of California Press |date=1992 |isbn=978-0-520-07827-7 |pages=124–125 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e5ZBNv-zTlQC&pg=PA124 |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194755/https://books.google.com/books?id=e5ZBNv-zTlQC&pg=PA124 |url-status=live }}</ref>。これらの結果は、特に[[エドゥアルト・ブフナー]]が酵母の無細胞抽出液中でアルコール発酵が起こることを証明した後、生気論に対する科学的関心の放棄につながった<ref>{{cite book | isbn= 978-8437-033280 | title= New Beer in an Old Bottle. Eduard Buchner and the Growth of Biochemical Knowledge | editor= Cornish-Bowden Athel | year=1997 | publisher = Universitat de València | place=Valencia, Spain}}</ref>。それにもかかわらず、疾病や病気が仮説上の生命力の障害によって引き起こされると解釈する[[ホメオパシー]]のような[[疑似科学]]理論への信仰は根強く残っている<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ncahf.org/pp/homeop.html |title=NCAHF Position Paper on Homeopathy |date=February 1994 |publisher=National Council Against Health Fraud |access-date=12 June 2012 |archive-date=25 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181225185228/https://www.ncahf.org/pp/homeop.html |url-status=live }}</ref>。 |

|||

多くの[[宗教]]では、何らかの形での[[死後の世界]]や[[輪廻]]、[[転生]]などが存在していると考えられている。 |

|||

== 発生 == |

|||

{{align|right|{{Life timeline}}}} |

|||

=== 生命の起源 === |

|||

{{Main|生命の起源}} |

|||

[[地球の年齢]]は約45億4000万年である<ref>{{cite journal |last=Dalrymple |first=G. Brent |title=The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved |journal=Special Publications, Geological Society of London |date=2001 |volume=190 |issue=1 |pages=205–221 |doi=10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14 |bibcode=2001GSLSP.190..205D|s2cid=130092094 }}</ref>。地球上の生命は少なくとも35億年前から存在しており<ref name="PNAS-20151014-pdf">{{cite journal |last1=Bell |first1=Elizabeth A. |last2=Boehnike |first2=Patrick |last3=Harrison |first3=T. Mark |last4=Mao |first4=Wendy L. |display-authors=3 |date=19 October 2015 |title=Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon |url=http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/10/14/1517557112.full.pdf |journal=PNAS |doi=10.1073/pnas.1517557112 |pmid=26483481 |pmc=4664351 |volume=112 |issue=47 |pages=14518–14521 |bibcode=2015PNAS..11214518B |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151106021508/http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/10/14/1517557112.full.pdf |archive-date=6 November 2015 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |title=Fossil evidence of Archaean life |journal=Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. |volume=361 |issue=1470 |pmc=1578735|doi=10.1098/rstb.2006.1834 |pmid=16754604 |date=June 2006 |pages=869–885 | last1 = Schopf | first1 = J.W.}}</ref><ref name="RavenJohnson2002">{{cite book |first1=Peter |last1=Hamilton Raven |first2=George |last2=Brooks Johnson |title=Biology |url=https://archive.org/details/biologyrave00rave |url-access=registration |date=2002 |publisher=McGraw-Hill Education |isbn=978-0-07-112261-0 |page=[https://archive.org/details/biologyrave00rave/page/68 68] |access-date=7 July 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first1=Clare |last1=Milsom |first2=Sue |last2=Rigby |author2-link=Sue Rigby |title=Fossils at a Glance |edition=2nd |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |date=2009 |isbn=978-1-4051-9336-8 |page=134 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OdrCdxr7QdgC&pg=PA134 |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=13 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230413194758/https://books.google.com/books?id=OdrCdxr7QdgC&pg=PA134 |url-status=live }}</ref>、最古の生命の物理的な[[生痕化石|痕跡]]は37億年前にさかのぼる<ref name="NG-20131208">{{cite journal |first1=Yoko |last1=Ohtomo |first2=Takeshi |last2=Kakegawa |first3=Akizumi |last3=Ishida |first4=Toshiro |last4=Nagase |first5=Minik T. |last5=Rosing |title=Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks |journal=[[:en:Nature Geoscience|Nature Geoscience]] |doi=10.1038/ngeo2025 |date=8 December 2013 |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=25–28 |bibcode=2014NatGe...7...25O}}</ref><ref name="AST-20131108">{{cite journal |last1=Noffke |first1=Nora |author-link=Nora Noffke |last2=Christian |first2=Daniel |last3=Wacey |first3=David |last4=Hazen |first4=Robert M. |title=Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia |date=8 November 2013 |journal=[[:en:Astrobiology (journal)|Astrobiology]] |volume=13 |issue=12 |pages=1103–1124 |doi=10.1089/ast.2013.1030 |bibcode=2013AsBio..13.1103N |pmid=24205812 |pmc=3870916}}</ref>。{{Ill2|TimeTree|en|TimeTree}}公開データベースにまとめられている分子時計からの推定では、生命の起源は約40億年前とされている<ref>{{cite book |last=Hedges |first=S. B. Hedges |chapter=Life |pages=89–98 |title=The Timetree of Life |editor1=S. B. Hedges |editor2=S. Kumar |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-1995-3503-3}}</ref>。生命の起源に関する仮説は、単純な[[有機分子]]から前細胞生命<!-- pre-cellular life -->を経て、{{Ill2|原始細胞|en|Protocell|label=}}<!-- protocells -->や代謝に至る{{Ill2|最終普遍共通祖先|en|Last universal common ancestor|label=普遍的な共通祖先}}の形成を説明しようとするものである<ref>{{cite web |url=http://phoenix.lpl.arizona.edu/mars145.php |title=Habitability and Biology: What are the Properties of Life? |access-date=6 June 2013 |website=Phoenix Mars Mission |publisher=The University of Arizona |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140417155949/http://phoenix.lpl.arizona.edu/mars145.php |archive-date=17 April 2014 }}</ref>。2016年、{{Ill2|最終普遍共通祖先|en|Last universal common ancestor|label=最後の普遍的共通祖先}}(LUCA)の355個の[[遺伝子]]セットが暫定的に同定された<ref name="NYT-20160725">{{cite news |last=Wade |first=Nicholas |author-link=Nicholas Wade |title=Meet Luca, the Ancestor of All Living Things |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/26/science/last-universal-ancestor.html |date=25 July 2016 |work=[[:en:The New York Times|The New York Times]] |access-date=25 July 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160728053822/http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/26/science/last-universal-ancestor.html |archive-date=28 July 2016 }}</ref>。 |

|||

生物圏は、生命の起源から少なくとも約35億年前に発達したと考えられている<ref name="Campbell 2006">{{cite book |last=Campbell |first=Neil A. |author2=Brad Williamson |author3=Robin J. Heyden |title=Biology: Exploring Life |publisher=Pearson Prentice Hall |year=2006 |location=Boston, Massachusetts |url=http://www.phschool.com/el_marketing.html |isbn=978-0-13-250882-7 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141102041816/http://www.phschool.com/el_marketing.html |archive-date=2 November 2014 |access-date=15 June 2016 }}</ref>。地球上の生命が存在した最古の証拠として、{{Ill2|Kitaa|en|Kitaa|label=西グリーンランド}}の37億年前の{{Ill2|変堆積岩|en|Metasedimentary rock}}から発見された{{Ill2|Biogenic substance|en|生体物質|label=生物起源}}の[[グラファイト]]や<ref name="NG-20131208" />、[[西オーストラリア州|西オーストラリア]]の34億8000万年前の[[砂岩]]から発見された{{Ill2|微生物マット|en|Microbial mat}}の[[化石]]があげられる<ref name="AST-20131108" />。さらに最近では、2015年に西オーストラリア州の41億年前の岩石から「生物学的生命の[[生体物質|遺跡]]」<!-- remains of biotic life -->が発見された<ref name="PNAS-20151014-pdf" />。2017年には、カナダ・ケベック州の{{Ill2|ヌブアギトゥク緑色岩帯|en|Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt|label=ヌブアギトゥク帯}}の[[熱水噴出孔]]の析出物から、地球最古の生命記録である42億8000万年前の[[微生物]](または[[微化石]])と推定される化石が発見されたと発表され、{{Ill2|地球上の水の起源|en|Origin of water on Earth|label=44億年前の海洋形成}}後、45億4000万年前の地球形成から間もない時期に「ほぼ瞬時に生命が出現した」ことが示唆された<ref name="NAT-20170301">{{cite journal |last1=Dodd |first1=Matthew S. |last2=Papineau |first2=Dominic |last3=Grenne |first3=Tor |last4=Slack |first4=John F. |last5=Rittner |first5=Martin |last6=Pirajno |first6=Franco |last7=O'Neil |first7=Jonathan |last8=Little |first8=Crispin T.S. |display-authors=3 |title=Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates |url=http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/112179/ |journal=[[:en:Nature (journal)|Nature]] |date=1 March 2017 |volume=543 |issue=7643 |pages=60–64 |doi=10.1038/nature21377 |pmid=28252057 |access-date=2 March 2017 |bibcode=2017Natur.543...60D |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170908201821/http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/112179/ |archive-date=8 September 2017 |doi-access=free }}</ref>。 |

|||

=== 進化 === |

=== 進化 === |

||

{{Main|進化}} |

|||

{{main|進化}} |

|||

== 人工生命 == |

|||

{{Main|人工生命}} |

|||

人間によって作成、またはシミュレーションされた生命体を人工生命と呼ぶ。特に近年の情報処理技術の発達にともなって、生命現象のシミュレーションをコンピュータ内("in silico")で行なうことも可能になった。文字通り「生命」を持つ人工生命を強い人工生命(strong Artificial Life, または Strong Alife)と呼び、限定された人工環境下で生命現象の一部だけをシミュレーションしたものを弱い人工生命(weak Alife)と呼ぶ<ref>Thro, E.: Artificial Life Explorer's Kit, SAMS Publishing.,1993.</ref>。強いAlifeが本当に実現可能であるのか、化学的プロセスと切り離されたコンピュータ上の計算が生命を持つと呼べるのかについては、さまざまな議論がある。 |

|||

[[進化]]とは、生物集団の[[遺伝]]的な[[形質]]が、世代を重ねるごとに変化することである。その結果、新しい種が出現し、しばしば古い種が消滅する<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hall |first1=Brian K. |author-link1=Brian K. Hall |last2=Hallgrímsson |first2=Benedikt |title=Strickberger's Evolution |url=https://archive.org/details/strickbergersevo0000hall |url-access=registration |year=2008 |edition=4th |location=Sudbury, Massachusetts |publisher=Jones and Bartlett Publishers |isbn=978-0-7637-0066-9 |lccn=2007008981 |oclc=85814089 |pages=[https://books.google.com/books?id=jrDD3cyA09kC&pg=PA4 4–6]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Evolution Resources |location=Washington, DC |publisher=[[:en:National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine|National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine]] |year=2016 |url=http://www.nas.edu/evolution/index.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160603230514/http://www.nas.edu/evolution/index.html |archive-date=3 June 2016 |access-date=2023-09-20}}</ref>。進化は、[[自然選択]]([[性選択]]を含む)や[[遺伝的浮動]]などの進化過程が遺伝的変異に作用し、その結果、世代を重ねるごとに集団内での特定の形質の頻度が増加または減少することで起こる<ref name="Scott-Phillips">{{cite journal |last1=Scott-Phillips |first1=Thomas C. |last2=Laland |first2=Kevin N. |author2-link=Kevin Laland |last3=Shuker |first3=David M. |last4=Dickins |first4=Thomas E. |last5=West |first5=Stuart A. |author-link5=Stuart West |display-authors=3 |date=May 2014 |title=The Niche Construction Perspective: A Critical Appraisal |journal=[[:en:Evolution (journal)|Evolution]] |volume=68 |issue=5 |pages=1231–1243 |doi=10.1111/evo.12332 |pmid=24325256 |pmc=4261998 |quote=Evolutionary processes are generally thought of as processes by which these changes occur. Four such processes are widely recognized: natural selection (in the broad sense, to include sexual selection), genetic drift, mutation, and migration (Fisher 1930; Haldane 1932). The latter two generate variation; the first two sort it.}}</ref>。進化の過程は、[[生命の階層|生物学的な組織]]のあらゆるレベルで[[生物多様性]]をもたらした<ref>{{harvnb|Hall|Hallgrímsson|2008|pp=3–5}}</ref><ref name="Voet2016a">{{cite book |last1=Voet |first1=Donald |author-link1=Donald Voet |last2=Voet |first2=Judith G. |author-link2=Judith G. Voet|last3=Pratt |first3=Charlotte W. |author-link3=Charlotte W. Pratt|year=2016 |title=Fundamentals of Biochemistry: Life at the Molecular Level |edition=Fifth |location=[[:en:Hoboken, New Jersey|Hoboken, New Jersey]] |publisher=[[:en:Wiley (publisher)|John Wiley & Sons]] |isbn=978-1-118-91840-1 |lccn=2016002847 |oclc=939245154 |at=Chapter 1: Introduction to the Chemistry of Life, pp. 1–22}}</ref>。 |

|||

コンピュータシミュレーションではない現実の生命については、2003年にゲノム解析の塩基配列情報からウイルスを合成することができたという報告がある<ref>[http://j.peopledaily.com.cn/2003/11/14/jp20031114_34084.html 2週間でウイルス合成 米、「人工微生物」実現に展望]</ref><ref>[http://www.nature.com/news/1998/031110/full/news031110-17.html Virus built from scratch in two weeks - Nature News]</ref>。 |

|||

その後2010年、アメリカのクレイグ・ベンター博士のチームはmycoplasmaのゲノムを表すほぼ完全なDNAを合成し、本来のDNAを除去された近縁種の細菌の細胞に、合成したDNAを移植する手法で、自立的に増殖する人工細菌を作成することに成功した。 |

|||

== |

=== 化石 === |

||

{{Main|地球外生命}} |

|||

21世紀初頭現在において、人類の知識の範囲内では、全ての生命体は地球上にしか存在しない。しかし、地球外生命の存在可能性は、古くから[[竹取物語#あらすじ|かぐや姫]]やウェルズの[[宇宙戦争 (H・G・ウェルズ)|宇宙戦争]]のような、おとぎ話やSFのインスピレーション元となってきた。また、近年の観測技術の発達に伴い、地球外生命体の存在可能性は真面目な科学的考察の対象となっている。[[カール・セーガン]]は、著書『コスモス』で、地球外生命体の存在可能性を数式を用いて提示した。[[太陽系]]内のいくつかの天体における生命存在の可能性については古くから議論がなされており、中でももっとも生命存在の可能性が高いとされる火星においては、1975年から1976年にかけて行われた[[バイキング計画]]において生命探査が行われたが、生命の痕跡を検出することはできなかった<ref>「生命の起源 宇宙・地球における化学進化」p146-p148 小林憲正 講談社 2013年5月20日第1刷発行</ref>。しかし、その後も火星生命の探索は行われている。このほか、地下に海の存在する可能性の高い[[木星]]の[[衛星]][[エウロパ (衛星)|エウロパ]]や[[土星]]の衛星[[エンケラドゥス (衛星)|エンケラドゥス]]、液体[[メタン]]や[[エタン]]による海が存在する土星の衛星[[タイタン (衛星)|タイタン]]なども生命の存在する可能性があると考えられている<ref>「生命の起源 宇宙・地球における化学進化」p164-p165 小林憲正 講談社 2013年5月20日第1刷発行</ref>([[タイタンの生命]]も参照)。 |

|||

{{main|化石}} |

|||

== 脚注 == |

|||

{{脚注ヘルプ}} |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

[[化石]]とは、古代に生息していた動物や植物、その他の生物の遺骸または[[生痕化石|痕跡]]が保存されたものである。発見された化石と未発見の化石の総体、および[[堆積岩]]の層([[地層]])におけるそれらの配置は、化石記録({{Lang-en-short|''fossil record''}})として知られている。保存された標本が1万年前の任意の年代よりも古い場合に化石と呼ばれる<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sdnhm.org/science/paleontology/resources/frequent/|title=Frequently Asked Questions|publisher=San Diego Natural History Museum|access-date=25 May 2012|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120510101706/http://sdnhm.org/science/paleontology/resources/frequent/|archive-date=10 May 2012}}</ref>。したがって化石の年代は、[[完新世]]の初期の最も若いものから、[[太古代]]の最も古いもの、34億年前のものまで幅広くある<ref>{{cite news |first1=Brian |last1=Vastag |title=Oldest 'microfossils' raise hopes for life on Mars |date=21 August 2011 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/oldest-microfossils-hail-from-34-billion-years-ago-raise-hopes-for-life-on-mars/2011/08/19/gIQAHK8UUJ_story.html?hpid=z3 |newspaper=The Washington Post |access-date=21 August 2011 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111019000458/http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/oldest-microfossils-hail-from-34-billion-years-ago-raise-hopes-for-life-on-mars/2011/08/19/gIQAHK8UUJ_story.html?hpid=z3 |archive-date=19 October 2011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first=Nicholas |last=Wade |title=Geological Team Lays Claim to Oldest Known Fossils |date=21 August 2011 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/22/science/earth/22fossil.html?_r=1&partner=rss&emc=rss&src=ig |work=The New York Times |access-date=21 August 2011 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130501085118/http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/22/science/earth/22fossil.html?_r=1&partner=rss&emc=rss&src=ig |archive-date=1 May 2013 }}</ref>。 |

|||

== 参考文献 == |

|||

* 山口裕之『ひとは生命をどのように理解してきたか』講談社、2011年 |

|||

* {{Cite book|和書|author1=野田春彦|authorlink1=野田春彦|author2=丸山工作|authorlink2=丸山工作|author3=日高敏隆|authorlink3=日高敏隆|coauthors = |others = |title = 新しい生物学 - 生命のナゾはどこまで解けたか|edition = 第3版|year = 1999|publisher = [[講談社]]|series = [[ブルーバックス]]|isbn = 978-4-06-257241-5|pages = }} |

|||

* {{Cite book|和書|author= 大島泰郎|authorlink=大島泰郎|others = |title = 宇宙生物学とET探査|origyear = |edition =第1刷 |year = 1994|publisher = [[朝日新聞社]] |isbn = 4-02-260798-X|page = |ref = 大島(1994)}} |

|||

== |

=== 絶滅 === |

||

{{Main|絶滅}} |

|||

絶滅とは、ある[[種 (分類学)|種]]のすべての個体が死に絶える過程のことである<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Extinction – definition |url=http://encarta.msn.com/dictionary_1861609974/extinction.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090926011523/http://encarta.msn.com/dictionary_1861609974/extinction.html |archive-date=26 September 2009 |url-status=dead}}</ref>。その種の最後の個体が死ぬときに絶滅の瞬間が訪れる。種の潜在的な[[分布 (生物)|生息範囲]]は非常に広い可能性があるため、この瞬間を決定するのは難しく、通常は明らかに不在の期間があった後に遡及的に行われる。種が絶滅するのは、[[生息地|生息環境]]の変化の中で、あるいは優れた競争相手に直面し、生き残ることができなくなったときに起こる。これまでに存在した種の99%以上が絶滅している<ref>{{cite web |url=http://palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk/Palaeofiles/Triassic/extinction.htm |title=What is an extinction? |website=Late Triassic |publisher=Bristol University |access-date=27 June 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120901011807/http://palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk/palaeofiles/triassic/extinction.htm |archive-date=1 September 2012 }}</ref><ref name="Book-Biology">{{cite book |editor1=Kunin, W.E. |editor2=Gaston, Kevin |author=McKinney, Michael L. |chapter=How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view |title=The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4LHnCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA110 |date=1996 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-0-412-63380-5 |access-date=26 May 2015 |archive-date=3 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230203051637/https://books.google.com/books?id=4LHnCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA110 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="StearnsStearns2000">{{cite book |last1=Stearns |first1=Beverly Peterson |last2=Stearns |first2=Stephen C. |title=Watching, from the Edge of Extinction |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0BHeC-tXIB4C&q=99+percent |year=2000 |publisher=[[:en:Yale University Press|Yale University Press]] |isbn=978-0-300-08469-6 |page=x |access-date=30 May 2017 |archive-date=5 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231105190204/https://books.google.com/books?id=0BHeC-tXIB4C&q=99+percent#v=snippet&q=99%20percent&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NYT-20141108-MJN">{{cite news |last=Novacek |first=Michael J. |title=Prehistory's Brilliant Future |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/09/opinion/sunday/prehistorys-brilliant-future.html |date=8 November 2014 |work=[[:en:The New York Times|The New York Times]] |access-date=25 December 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141229225657/http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/09/opinion/sunday/prehistorys-brilliant-future.html |archive-date=29 December 2014 }}</ref>。[[大量絶滅]]によって、新しい生物群が多様化する機会がもたらされ、進化を加速させた可能性がある<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Van Valkenburgh |first=B. |author-link=Blaire Van Valkenburgh |date=1999 |title=Major patterns in the history of carnivorous mammals |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |volume=27 |pages=463–493 |doi=10.1146/annurev.earth.27.1.463 |bibcode=1999AREPS..27..463V |url=https://zenodo.org/record/890156 |access-date=29 June 2019 |archive-date=29 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200229201201/https://zenodo.org/record/890156 |url-status=live }}</ref>。 |

|||

== 環境条件 == |

|||

[[File:20100422 235222 Cyanobacteria.jpg|thumb|upright=0.9|[[シアノバクテリア]]は地球上の生物の構成を{{Ill2|大酸化イベント|en|Great Oxidation Event|label=劇的に変化させ}}、酸素不耐性の生物をほぼ絶滅するまでに追い込んだ]] |

|||

地球上の生物の多様性は、{{Ill2|遺伝的機会|en|Genetic opportunity}}、代謝能力、[[自然環境|環境]]的課題<ref name="astrobiology">{{cite web |url=http://astrobiology.arc.nasa.gov/roadmap/g5.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120329092237/http://astrobiology.arc.nasa.gov/roadmap/g5.html |archive-date=29 March 2012 |url-status=dead |title=Understand the evolutionary mechanisms and environmental limits of life |access-date=13 July 2009 |last=Rothschild |first=Lynn |author-link=Lynn J. Rothschild |date=September 2003 |publisher=NASA}}</ref>、および[[共生]]<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Symbiosis and the origin of life |journal=Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres |date=April 1977 |first=G.A.M. |last=King |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=39–53 |doi=10.1007/BF00930938 |pmid=896191 |bibcode=1977OrLi....8...39K|s2cid=23615028 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Margulis |first=Lynn |author-link=Lynn Margulis |title=The Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution |publisher=Orion Books |date=2001 |location=London|isbn=978-0-7538-0785-9}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Futuyma |first1=D.J. |author1-link=Douglas J. Futuyma |author2=Janis Antonovics |title=Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology: Symbiosis in evolution |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1992 |volume=8 |location=London, England |pages=347–374 |isbn=978-0-19-507623-3}}</ref>が動的に相互作用した結果である。地球上で生存可能な環境は、そのほとんどの期間は微生物によって支配され、その代謝と進化の影響を受けてきた。こうした微生物の活動の結果、地球上の物理化学的な環境は[[地質年代|地質学的な時間尺度]]で変化し、その後の生命の進化の道筋に影響を与えてきた<ref name="astrobiology" />。たとえば、[[シアノバクテリア]]が[[光合成]]の副産物として[[酸素]]分子を放出したことで、地球規模で環境変化が引き起こされた。酸素は当時の地球上のほとんどの生物にとって有毒であったため、酸素の増加は新たな進化的課題をもたらし、やがて地球の主要な動植物種の形成につながった。このような生物と環境の相互作用は、生体系に固有の特徴である<ref name="astrobiology" />。 |

|||

=== 生物圏 === |

|||

{{main|生物圏}} |

|||

[[File:Deinococcus geothermalis cells.jpg|thumb|{{Ill2|デイノコッカス・ジオテルマリス|en|Deinococcus geothermalis}}({{Snamei|Deinococcus geothermalis}})は、[[熱水泉]]や深海底表層で繁殖する細菌である<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Liedert |first1=Christina |last2=Peltola |first2=Minna |last3=Bernhardt |first3=Jörg |last4=Neubauer |first4=Peter |last5=Salkinoja-Salonen |first5=Mirja |date=2012-03-15 |title=Physiology of Resistant Deinococcus geothermalis Bacterium Aerobically Cultivated in Low-Manganese Medium |journal=Journal of Bacteriology |language=en |volume=194 |issue=6 |pages=1552–1561 |doi=10.1128/JB.06429-11 |pmc=3294853 |pmid=22228732}}</ref>|left]] |

|||

[[生物圏]]とは、すべての生態系の総体である。それらは「地球上の生活圏」とも呼ばれ、(太陽や宇宙からの放射線と地球内部からの熱を除いて)[[閉鎖系]]であり、大部分は自己調節されている<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=The Columbia Encyclopedia|edition=6th |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2004 |url=https://www.questia.com/library/encyclopedia/biosphere.jsp |url-status= |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111027194858/http://www.questia.com/library/encyclopedia/biosphere.jsp |archive-date=27 October 2011 |title=Biosphere }}</ref>。生物は<!-- 代謝しているとは限らない -->、[[土壌]]、[[熱水泉]]、地下{{convert|12|mi|km|order=flip|abbr=on}}以上の{{Ill2|岩石内微生物|en|Endolith|label=岩石内部}}、海洋の最深部、そして大気圏上空{{convert|40|mi|km|order=flip|abbr=on}}以上など、生物圏のあらゆる場所に存在する<ref name="SD-19980625-UG">{{cite web |author=University of Georgia |title=First-Ever Scientific Estimate Of Total Bacteria On Earth Shows Far Greater Numbers Than Ever Known Before |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/08/980825080732.htm |date=25 August 1998 |website=[[:en:Science Daily|Science Daily]] |access-date=10 November 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141110162101/https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/08/980825080732.htm |archive-date=10 November 2014 }}</ref><ref name="ABM-20150112">{{cite web |last=Hadhazy |first=Adam |title=Life Might Thrive a Dozen Miles Beneath Earth's Surface |url=http://www.astrobio.net/extreme-life/life-might-thrive-dozen-miles-beneath-earths-surface/ |date=12 January 2015 |website=[[:en:Astrobiology Magazine|Astrobiology Magazine]] |access-date=11 March 2017 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170312065614/http://www.astrobio.net/extreme-life/life-might-thrive-dozen-miles-beneath-earths-surface/ |archive-date=12 March 2017 }}</ref><ref name="BBC-20151124">{{cite web |last=Fox-Skelly |first=Jasmin |title=The Strange Beasts That Live in Solid Rock Deep Underground |url=http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20151124-meet-the-strange-creatures-that-live-in-solid-rock-deep-underground |date=24 November 2015 |website=[[:en:BBC online|BBC online]] |access-date=11 March 2017 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161125013248/http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20151124-meet-the-strange-creatures-that-live-in-solid-rock-deep-underground |archive-date=25 November 2016 }}</ref>。たとえば、{{Ill2|アスペルギルス・ニゲル|en|Aspergillus niger}}({{Snamei|Aspergillus niger}})の胞子は、高度48-77 kmの[[中間圏]]で検出されている<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Imshenetsky |first1=AA |last2=Lysenko |first2=SV |last3=Kazakov |first3=GA |date=June 1978 |title=Upper boundary of the biosphere |journal=Applied and Environmental Microbiology |volume=35 |issue=1 |pages=1–5 |doi=10.1128/aem.35.1.1-5.1978 |pmc=242768 |pmid=623455|bibcode=1978ApEnM..35....1I }}</ref>。実験室的な条件下では、生命体は{{Ill2|無重力|en|Weightlessness#Effects on non human organisms|label=無重力に近い宇宙空間|preserve=1}}で繁栄し<ref name="GZM-20170913">{{cite web |last=Dvorsky |first=George |title=Alarming Study Indicates Why Certain Bacteria Are More Resistant to Drugs in Space |url=https://gizmodo.com/alarming-study-indicates-why-certain-bacteria-are-more-1805666249 |date=13 September 2017 |website=[[:en:Gizmodo|Gizmodo]] |access-date=14 September 2017 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170914011750/http://gizmodo.com/alarming-study-indicates-why-certain-bacteria-are-more-1805666249 |archive-date=14 September 2017 }}</ref><ref name="ASU-20070923">{{cite web |last=Caspermeyer |first=Joe |title=Space flight shown to alter ability of bacteria to cause disease |url=https://biodesign.asu.edu/news/space-flight-shown-alter-ability-bacteria-cause-disease |date=23 September 2007 |website=[[:en:Arizona State University|Arizona State University]] |access-date=14 September 2017 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170914172718/https://biodesign.asu.edu/news/space-flight-shown-alter-ability-bacteria-cause-disease |archive-date=14 September 2017 }}</ref>、真空の宇宙空間でも生存することが観察されている<ref name="Dose">{{cite journal |title=ERA-experiment "space biochemistry" |journal=Advances in Space Research |volume=16 |issue=8 |year=1995 |pages=119–129 |doi=10.1016/0273-1177(95)00280-R |pmid=11542696 |last1=Dose |first1=K. |last2=Bieger-Dose |first2=A. |last3=Dillmann |first3=R. |last4=Gill |first4=M. |last5=Kerz |first5=O. |last6=Klein |first6=A. |last7=Meinert |first7=H. |last8=Nawroth |first8=T. |last9=Risi |first9=S. | last10=Stridde | first10=C. |display-authors=3 |bibcode=1995AdSpR..16h.119D}}</ref><ref name="Horneck">{{cite journal |title=Biological responses to space: results of the experiment "Exobiological Unit" of ERA on EURECA I |journal=Adv. Space Res. |year=1995 |author1=Horneck G. |author2=Eschweiler, U. |author3=Reitz, G. |author4=Wehner, J. |author5=Willimek, R. |author6=Strauch, K. |volume=16 |issue=8 |pages=105–118 |pmid=11542695 |bibcode=1995AdSpR..16h.105H |doi=10.1016/0273-1177(95)00279-N}}</ref>。生命体は、深い[[マリアナ海溝]]や<ref name="NG-20130317">{{cite journal |last1=Glud |first1=Ronnie |last2=Wenzhöfer |first2=Frank |last3=Middelboe |first3=Mathias |last4=Oguri |first4=Kazumasa |last5=Turnewitsch |first5=Robert |last6=Canfield |first6=Donald E. |last7=Kitazato |first7=Hiroshi |display-authors=3 |title=High rates of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth |doi=10.1038/ngeo1773 |date=17 March 2013 |journal=[[:en:Nature Geoscience|Nature Geoscience]] |volume=6 |issue=4 |pages=284–288 |bibcode=2013NatGe...6..284G}}</ref>、米国北西部沖の水深{{convert|2590|m|ft mi|abbr=on}}の海底下{{convert|580|m|ft mi|abbr=on}}以上の岩石中<ref name="LS-20130317">{{cite web |last=Choi |first=Charles Q. |title=Microbes Thrive in Deepest Spot on Earth |url=http://www.livescience.com/27954-microbes-mariana-trench.html |date=17 March 2013 |publisher=[[:en:LiveScience|LiveScience]] |access-date=17 March 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130402234623/http://www.livescience.com/27954-microbes-mariana-trench.html |archive-date=2 April 2013 }}</ref><ref name="LS-20130314">{{cite web |last=Oskin |first=Becky |title=Intraterrestrials: Life Thrives in Ocean Floor |url=http://www.livescience.com/27899-ocean-subsurface-ecosystem-found.html |date=14 March 2013 |publisher=[[:en:LiveScience|LiveScience]] |access-date=17 March 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130402235647/http://www.livescience.com/27899-ocean-subsurface-ecosystem-found.html |archive-date=2 April 2013 }}</ref>、あるいは日本沖合の海底{{convert|2400|m|ft mi|abbr=on}}でも繁栄している<ref name="BBC-20141215-RM">{{cite news |last=Morelle |first=Rebecca |author-link=Rebecca Morelle |title=Microbes discovered by deepest marine drill analysed |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-30489814 |date=15 December 2014 |work=[[:en:BBC News|BBC News]] |access-date=15 December 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141216185424/http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-30489814 |archive-date=16 December 2014 }}</ref>。2014年には、南極大陸の氷の下{{convert|800|m|ft mi|abbr=on}}に生息する生命体が発見された<ref name="NAT-20140820">{{cite journal |last=Fox |first=Douglas |title=Lakes under the ice: Antarctica's secret garden |date=20 August 2014 |journal=[[:en:Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=512 |issue=7514 |pages=244–246 |doi=10.1038/512244a |bibcode=2014Natur.512..244F |pmid=25143097 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="FRB-20140820">{{cite web |last=Mack |first=Eric |title=Life Confirmed Under Antarctic Ice; Is Space Next? |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/ericmack/2014/08/20/life-confirmed-under-antarctic-ice-is-space-next/ |date=20 August 2014 |website=[[:en:Forbes|Forbes]] |access-date=21 August 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140822002442/http://www.forbes.com/sites/ericmack/2014/08/20/life-confirmed-under-antarctic-ice-is-space-next/ |archive-date=22 August 2014 }}</ref>。{{Ill2|国際海洋発見プログラム|en|International Ocean Discovery Program}}による探検で、[[南海トラフ]]の[[沈み込み帯]]の海底下1.2 kmの120 ℃の堆積物から[[単細胞生物]]が発見された<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Heuer |first1=Verena B. |last2=Inagaki |first2=Fumio |last3=Morono |first3=Yuki |last4=Kubo |first4=Yusuke |last5=Spivack |first5=Arthur J. |last6=Viehweger |first6=Bernhard |last7=Treude |first7=Tina |last8=Beulig |first8=Felix |last9=Schubotz |first9=Florence |last10=Tonai |first10=Satoshi |last11=Bowden |first11=Stephen A. |display-authors=3 |date=4 December 2020 |title=Temperature limits to deep subseafloor life in the Nankai Trough subduction zone |journal=Science |volume=370 |issue=6521 |pages=1230–1234 |doi=10.1126/science.abd7934 |pmid=33273103 |bibcode=2020Sci...370.1230H |hdl=2164/15700 |s2cid=227257205 |url=https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5b65v425 |hdl-access=free |access-date=5 November 2023 |archive-date=26 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220926003958/https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5b65v425 |url-status=live }}</ref>。ある研究者は、「[[微生物]]はどこにでも生息している。条件への適応性が極めて高く、どこにいても生き延びることができる」と述べている<ref name="LS-20130317" />。 |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

=== 耐性域 === |

|||