「エミー・ネーター」の版間の差分

文章整理、スタイル調整など |

from en:Emmy_Noether, oldid=717409314. もとの日本語のはほぼ残してあり重複するので調整が必要.翻訳中途. タグ: サイズの大幅な増減 |

||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

遅々として進まない |

|||

{{翻訳中途|1=[[en:Emmy Noether]]|date=2016年4月}} |

|||

{{翻訳直後|1=[[en:Emmy Noether]]|date=2016年4月}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2015}} |

|||

{{Infobox scientist |

{{Infobox scientist |

||

| name = アマーリエ・エミー・ネーター<br />Amalie Emmy Noether |

| name = アマーリエ・エミー・ネーター<br />Amalie Emmy Noether |

||

| 6行目: | 10行目: | ||

| caption = アマーリエ・エミー・ネーター |

| caption = アマーリエ・エミー・ネーター |

||

| birth_date = {{生年月日と年齢|1882|3|23|死去}} |

| birth_date = {{生年月日と年齢|1882|3|23|死去}} |

||

| birth_place = {{DEU1871}} [[バイエルン州]][[エアランゲン]] |

| birth_place = {{DEU1871}} [[バイエルン州]][[エアランゲン|エルランゲン]] |

||

| death_date = {{死亡年月日と没年齢|1882|3|23|1935|4|14}} |

| death_date = {{死亡年月日と没年齢|1882|3|23|1935|4|14}} |

||

| death_place = {{USA}} [[ペンシルベニア州]] |

| death_place = {{USA}} [[ペンシルベニア州]]{{仮リンク|ブリンマー|en|Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania}} |

||

| residence = |

| residence = |

||

| citizenship = {{GER}} |

| citizenship = {{GER}} |

||

| nationality = |

| nationality = |

||

| fields = [[数学]]、[[物理学]] |

| fields = [[数学]]、[[物理学]] |

||

| workplaces = [[ゲオルク・アウグスト大学ゲッティンゲン]]<br /> |

| workplaces = [[ゲオルク・アウグスト大学ゲッティンゲン]]<br />{{仮リンク|ブリンマー大学|en|Bryn Mawr College}} |

||

| alma_mater = [[フリードリヒ・アレクサンダー大学エアランゲン=ニュルンベルク]] |

| alma_mater = [[フリードリヒ・アレクサンダー大学エアランゲン=ニュルンベルク|フリードリヒ・アレクサンダー大学エルランゲン=ニュルンベルク]] |

||

| doctoral_advisor = |

| doctoral_advisor = {{仮リンク|パウル・ゴルダン|en|Paul Gordan}} |

||

| academic_advisors = |

| academic_advisors = |

||

| doctoral_students = |

| doctoral_students = {{仮リンク|マックス・ドイリング|en|Max Deuring}}<br />{{仮リンク|ハンス・フィッティング|en|Hans Fitting}}<br />{{仮リンク|グレーテ・ヘルマン|en|Grete Hermann}}<br />{{仮リンク|曾炯之|en|Zeng Jiongzhi}}<br />{{仮リンク|ヤコブ・レヴィツキ|en|Jacob Levitzki}}<br />{{仮リンク|オットー・シリンク|en|Otto Schilling}}<br />[[エルンスト・ヴィット]] |

||

| notable_students = |

| notable_students = |

||

| known_for = [[抽象代数学]]<br />[[理論物理学]] |

| known_for = [[抽象代数学]]<br />[[理論物理学]] |

||

| 24行目: | 28行目: | ||

| influences = |

| influences = |

||

| influenced = |

| influenced = |

||

| awards = {{仮リンク|アッケルマン・トイブナー記念賞|en|Ackermann–Teubner Memorial Award}}<small>(1932)</small> |

|||

| awards = |

|||

| signature = <!--(ファイル名のみ)--> |

| signature = <!--(ファイル名のみ)--> |

||

| signature_alt = |

| signature_alt = |

||

| footnotes = |

| footnotes = <!--For any footnotes needed to clarify entries above--> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

''' |

'''エミー・ネーター''' (Emmy Noether) ({{IPA-de|ˈnøːtɐ|lang}}; official name '''Amalie Emmy Noether''';<ref>[[Emmy (given name)|Emmy]] is the ''[[Rufname]]'', the second of two official given names, intended for daily use. Cf. for example the résumé submitted by Noether to Erlangen University in 1907 (Erlangen University archive, ''Promotionsakt Emmy Noether'' (1907/08, NR. 2988); reproduced in: ''Emmy Noether, Gesammelte Abhandlungen – Collected Papers,'' ed. N. Jacobson 1983; online facsimile at [http://www.physikerinnen.de/noetherlebenslauf.html physikerinnen.de/noetherlebenslauf.html]). Sometimes ''Emmy'' is mistakenly reported as a short form for ''Amalie'', or misreported as "Emily". e.g. {{Citation | url = http://www.edge.org/documents/archive/edge52.html | author-link = Lee Smolin | first = Lee | last = Smolin | work = Edge | title = Special Relativity – Why Can't You Go Faster Than Light? | quote = Emily Noether, a great German mathematician}}.</ref> [[1882年]][[3月23日]] - [[1935年]][[4月14日]]) は[[ユダヤ系]][[ドイツ人]][[数学者]]。[[抽象代数学]]と[[理論物理学]]への多大な貢献で有名。ネーターは、{{仮リンク|パヴェル・アレクサンドロフ|en|Pavel Alexandrov}}、[[アルベルト・アインシュタイン]]、[[ジャン・ディュドネ]]、[[ヘルマン・ヴァイル]]、{{仮リンク|ノーバート・ウィーナー|en|Norbert Wiener}}によって、数学の歴史において最も重要な女性と評されている<ref name = "einstein" />{{Sfn | Alexandrov | 1981 | p = 100}}<ref>[[レオン・レーダーマン]]によれば「歴史上最も偉大な数学者の一人」であり(レオン・レーダーマン、クリストファー・ヒル共著、小林茂樹訳『対称性』第3章、白揚社 ISBN978-4-8269-0133-4)、[[アルベルト・アインシュタイン]]によれば「(物理学に)最も価値ある貢献をした数学者」である(1935年5月4日『[[ニューヨーク・タイムズ]]』紙に寄稿した弔文。[[q:en:Albert Einstein#Obituary for Emmy Noether (1935)|Obituary for Emmy Noether]])。</ref>。彼女の時代の先導的数学者の一人として、彼女は[[環 (数学)|環]]、[[可換体|体]]、[[体上の多元環|多元環]]の理論を発展させた。物理学では、[[ネーターの定理]]は{{仮リンク|物理における対称性|label=対称性|en|symmetry in physics}}と[[保存則]]の間の関係を説明する<ref name = "neeman_1999" />。<!--[[環論]]において重要な概念である[[ネーター環]]を提唱した。[[対称性]]があるところには それに対応する[[保存則]]が存在するという[[ネーターの定理]]は[[物理学]]の分野の基本定理である。--> |

||

ネーターは[[エルランゲン]]の[[フランケン地方]]の町のユダヤの家系に生まれた。父は数学者の{{仮リンク|マックス・ネーター|en|Max Noether}}である。彼女はもともと、必要な試験を通った後フランス語と英語を教える予定だったが、代わりに数学を彼女の父が講義している[[エルランゲン大学]]で学んだ。{{仮リンク|パウル・ゴルダン|en|Paul Gordan}}の指導の下1907年に学位論文を完成させた後、彼女は7年間無給で Mathematical Institute of Erlangen で働いた。当時女性は academic position から largely exclude されていた。1915年、彼女は[[ダフィット・ヒルベルト]] (David Hilbert) と[[フェリックス・クライン]] (Felix Klein) によって[[ゲッチンゲン大学]]数学科、世界規模で有名な数学研究の中心、に招かれた。しかしながら、哲学的な教授陣は反対し、彼女は4年間をヒルベルトの名の下での講義に費やした。彼女の ''{{仮リンク|habilitation|en|habilitation}}'' が1919年に承認され、彼女は ''{{仮リンク|Privatdozent|en|Privatdozent}}'' の地位を得ることができた。 |

|||

[[環論]]において重要な概念である[[ネーター環]]を提唱した。[[対称性]]があるところには それに対応する[[保存則]]が存在するという[[ネーターの定理]]は[[物理学]]の分野の基本定理である。 |

|||

ネーターは1933年までゲッチンゲン数学科の主導的一員だった。彼女の生徒は "Noether boys" と呼ばれることもあった。1924年、オランダ人数学者 [[Bartel Leendert van der Waerden|B. L. ファン・デル・ヴェルデン]]は彼女の circle に入り、すぐにネーターのアイデアの主導的解説者になった。彼女の仕事は彼の影響の大きい1931年の教科書 ''{{仮リンク|Moderne Algebra|en|Moderne Algebra}}''(現代代数学)の第二巻の基礎であった。1932年の[[チューリッヒ]]での[[国際数学者会議]]での彼女の plenary address の時までには彼女の代数的な洞察力は世界中で認められていた。翌年、ドイツのナチ政府はユダヤ人を大学の職から解雇し、ネーターはアメリカに移って[[ペンシルヴァニア]]の {{仮リンク|Bryn Mawr College|en|Bryn Mawr College}} で職を得た。1935年、彼女は[[卵巣嚢腫]]の手術を受け、回復の兆しにもかかわらず、4日後53歳で亡くなった。 |

|||

ネーターの数学的研究は3つの「時代」に分けられている<ref name=Weyl>{{Harvnb|Weyl|1935}}</ref>。第一の時代 (1908–19)、彼女は{{仮リンク|代数的不変量|en|algebraic invariant}}と[[可換体|数体]]の理論に貢献した。[[変分法]]における微分不変量に関する彼女の仕事、''[[ネーターの定理]]''は、「現代物理学の発展を先導したこれまでに証明された最も重要な数学な定理の1つ」と呼ばれてきた{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p =73}}。第二の時代 (1920–26)、彼女は「[抽象]代数学の顔を変えた」仕事を始めた<ref name="weyl_128" />。彼女の高尚な論文 ''Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen'' (''Theory of Ideals in Ring Domains'', 1921) においてネーターは[[可換環]]の[[イデアル]]の理論を広範囲な応用を持つ道具へと発展させた。彼女は[[昇鎖条件]]を手際よく使い、彼女に敬意を表してそれを満たす対象は{{仮リンク|ネーター的|label=''ネーター''(''的'')|en|Noetherian (disambiguation)}}と呼ばれる。第三の時代 (1927–35)、彼女は[[非可換代数]]と[[超複素数]]についての研究を出版し、[[群 (数学)|群]]の[[表現論]]を[[環上の加群|加群]]とイデアルの理論と統合した。彼女自身の出版物に加え、ネーターは彼女の考えに惜しみなく、他の数学者によって出版されたいろいろな研究の功績が、[[代数的位相幾何学]]のような彼女の研究とはかけ離れた分野においてさえ、認められている。 |

|||

== 経歴 == |

== 経歴 == |

||

著名な数学教授の{{仮リンク|マックス・ネーター|en|Max Noether}}の娘として、[[ドイツ帝国]]の[[エ |

著名な数学教授の{{仮リンク|マックス・ネーター|en|Max Noether}}の娘として、[[ドイツ帝国]]の[[エルランゲン]]で生まれた。弟のフリッツ・ネーターも後に数学者となる。 |

||

ネーターの当初の希望は、[[英語]]と[[フランス語]]の教師になることだった。しかし、ネーターは、数学者へ進路を変えた。当初は聴講を認められた[[ゲオルク・アウグスト大学ゲッティンゲン|ゲッティンゲン大学]]の講義を受けていたが、健康を害してエ |

ネーターの当初の希望は、[[英語]]と[[フランス語]]の教師になることだった。しかし、ネーターは、数学者へ進路を変えた。当初は聴講を認められた[[ゲオルク・アウグスト大学ゲッティンゲン|ゲッティンゲン大学]]の講義を受けていたが、健康を害してエルランゲンに戻った。前後して[[バイエルン王国|バイエルン]]では、[[1903年]]に女性の大学入学が許されるようになり、これによってネーターは[[フリードリヒ・アレクサンダー大学エルランゲン=ニュルンベルク|エアランゲン大学]]に入学し、{{仮リンク|パウル・ゴーダン|en|Paul Gordan}}のもとで[[1907年]]に[[学位]]を所得した。1909年には[[ドイツ数学会]]への入会を認められた。 |

||

[[1909年]]に[[ダフィット・ヒルベルト]]に招かれて、再びゲッティンゲン大学に移り、ヒルベルトほか、[[ヘルマン・ミンコフスキー]]、[[フェリックス・クライン]]に学んだ。[[1915年]]、ヒルベルトはネーターを[[教授]]にすべく活動したが、当時は[[女性差別]]の時代であり困難を極めた。難色を示す教授陣にヒルベルトは業を煮やし、「これは大学の問題であって[[銭湯]]の問題ではない」と激怒した<ref>[[岡部恒治]]・藤岡文世 (1996) 『マンガ幾何入門』[[講談社]][[ブルーバックス]] |

[[1909年]]に[[ダフィット・ヒルベルト]]に招かれて、再びゲッティンゲン大学に移り、ヒルベルトほか、[[ヘルマン・ミンコフスキー]]、[[フェリックス・クライン]]に学んだ。[[1915年]]、ヒルベルトはネーターを[[教授]]にすべく活動したが、当時は[[女性差別]]の時代であり困難を極めた。難色を示す教授陣にヒルベルトは業を煮やし、「これは大学の問題であって[[銭湯]]の問題ではない」と激怒した<ref>[[岡部恒治]]・藤岡文世 (1996) 『マンガ幾何入門』[[講談社]][[ブルーバックス]] p. 281</ref>。ヒルベルトの活動が実り、ネーターは1919年にゲッティンゲン大学で助教授になった。 |

||

ネーターは、この間ゲッティンゲン大学において[[ネーターの定理]]の完成や、[[環 (数学)|環]]論など[[代数学|代数]]の分野で優れた業績を挙げた。ネーターの定理は、「[[作用]]が、ある連続変換に対して不変ならば([[対称性]]があるならば)、これに付随した[[保存量]]が存在する」という内容で、後の[[場の量子論]]で重要な定理となる。 |

ネーターは、この間ゲッティンゲン大学において[[ネーターの定理]]の完成や、[[環 (数学)|環]]論など[[代数学|代数]]の分野で優れた業績を挙げた。ネーターの定理は、「[[作用]]が、ある連続変換に対して不変ならば([[対称性]]があるならば)、これに付随した[[保存量]]が存在する」という内容で、後の[[場の量子論]]で重要な定理となる。 |

||

| 46行目: | 54行目: | ||

[[1935年]]、[[卵巣癌]]により{{仮リンク|ブリンマー|en|Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania}}にて死去。満53歳没。遺灰はブリンマー大学の図書館を囲む通路の下に埋葬された。 |

[[1935年]]、[[卵巣癌]]により{{仮リンク|ブリンマー|en|Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania}}にて死去。満53歳没。遺灰はブリンマー大学の図書館を囲む通路の下に埋葬された。 |

||

== |

==Private life== |

||

[[File:Erlangen 1916.jpg|thumb|Noether grew up in the Bavarian city of [[Erlangen]], depicted here in a 1916 postcard]] |

|||

[[File:NoetherFamily MFO3120.jpg|thumb|Emmy Noether with her brothers Alfred, [[Fritz Noether|Fritz]], and Robert, before 1918]] |

|||

エミーの父{{仮リンク|マックス・ネーター|en|Max Noether}} (Max Noether) はドイツの卸売り商人の家系の出であった。14のとき[[急性灰白髄炎|ポリオ]]で麻痺した。動けるようにはなったが片脚は後遺症が残った。Largely self-taught, he was awarded a [[doctorate]] from the [[University of Heidelberg]] in 1868. After teaching there for seven years, he took a position in the Bavarian city of [[Erlangen]], where he met and married Ida Amalia Kaufmann, the daughter of a prosperous merchant.{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=3–5}}{{Sfn |Osen | 1974 |p=142}}{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|pp=70–71}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=7–9}} Max Noether's mathematical contributions were to [[algebraic geometry]] mainly, following in the footsteps of [[Alfred Clebsch]]. His best known results are the ''[[Brill–Noether theorem]]'' and the residue, or ''[[AF+BG theorem]]''; several other theorems are associated with him, including ''[[Max Noether's theorem (disambiguation)|Max Noether's]].'' |

|||

Emmy Noether was born on 23 March 1882, the first of four children. Her first name was "Amalie", after her mother and paternal grandmother, but she began using her middle name at a young age. As a girl, Noether was well liked. She did not stand out academically although she was known for being clever and friendly. She was [[near-sighted]] and talked with a minor [[lisp]] during childhood. A family friend recounted a story years later about young Noether quickly solving a brain teaser at a children's party, showing logical acumen at that early age.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 9–10}} She was taught to cook and clean, as were most girls of the time, and she took piano lessons. She pursued none of these activities with passion, although she loved to dance.{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p= 142}}{{Sfn | Dick | 1981|pp=10–11}} |

|||

She had three younger brothers. The eldest, Alfred, was born in 1883, was awarded a doctorate in [[chemistry]] from Erlangen in 1909, but died nine years later. [[Fritz Noether]], born in 1884, is remembered for his academic accomplishments: after studying in [[Munich]] he made a reputation for himself in [[applied mathematics]]. The youngest, Gustav Robert, was born in 1889. Very little is known about his life; he suffered from chronic illness and died in 1928.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=25, 45}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|p= 5}} |

|||

==Teaching== |

|||

===University of Erlangen=== |

|||

[[File:Paul Albert Gordan.jpg|thumb|[[Paul Gordan]] supervised Noether's doctoral dissertation on [[invariant (mathematics)|invariants]] of biquadratic forms.]] |

|||

Noether showed early proficiency in French and English. In the spring of 1900 she took the examination for teachers of these languages and received an overall score of ''sehr gut'' (very good). Her performance qualified her to teach languages at schools reserved for girls, but she chose instead to continue her studies at the [[University of Erlangen]]. |

|||

This was an unconventional decision; two years earlier, the Academic Senate of the university had declared that allowing [[mixed-sex education]] would "overthrow all academic order".{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p= 10}} One of only two women students in a university of 986, Noether was only allowed to [[academic audit|audit]] classes rather than participate fully, and required the permission of individual professors whose lectures she wished to attend. Despite these obstacles, on 14 July 1903 she passed the graduation exam at a ''[[Realgymnasium]]'' in [[Nuremberg]].{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=11–12}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=8–10}}{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p= 71}} |

|||

During the 1903–04 winter semester, she studied at the University of Göttingen, attending lectures given by astronomer [[Karl Schwarzschild]] and mathematicians [[Hermann Minkowski]], [[Otto Blumenthal]], [[Felix Klein]], and [[David Hilbert]]. Soon thereafter, restrictions on women's participation in that university were rescinded. |

|||

Noether returned to Erlangen. She officially reentered the university on 24 October 1904, and declared her intention to focus solely on mathematics. Under the supervision of [[Paul Gordan]] she wrote her dissertation, ''Über die Bildung des Formensystems der ternären biquadratischen Form'' (''On Complete Systems of Invariants for Ternary Biquadratic Forms'', 1907). Although it had been well received, Noether later described her thesis as "crap".{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=10–11}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=13–17}}<ref>{{Harvnb|Lederman|Hill|2004|p=71}} write that she completed her doctorate at Göttingen, but this appears to be an error.</ref> |

|||

For the next seven years (1908–15) she taught at the University of Erlangen's Mathematical Institute without pay, occasionally substituting for her father when he was too ill to lecture. In 1910 and 1911 she published an extension of her thesis work from three variables to ''n'' variables. |

|||

[[File:Emmy noether postcard 1915.jpg|thumb|250px|upright|Noether sometimes used postcards to discuss abstract algebra with her colleague, Ernst Fischer. this card is postmarked 10 April 1915.]] |

|||

Gordan retired in the spring of 1910, but continued to teach occasionally with his successor, [[Erhard Schmidt]], who left shortly afterward for a position in [[Breslau]]. Gordan retired from teaching altogether in 1911 with the arrival of Schmidt's successor [[Ernst Sigismund Fischer|Ernst Fischer]], and died in December 1912. |

|||

According to [[Hermann Weyl]], Fischer was an important influence on Noether, in particular by introducing her to the work of [[David Hilbert]]. From 1913 to 1916 Noether published several papers extending and applying Hilbert's methods to mathematical objects such as [[field (mathematics)|fields]] of [[rational function]]s and the [[invariant theory|invariants]] of [[finite group]]s. This phase marks the beginning of her engagement with [[abstract algebra]], the field of mathematics to which she would make groundbreaking contributions. |

|||

Noether and Fischer shared lively enjoyment of mathematics and would often discuss lectures long after they were over; Noether is known to have sent postcards to Fischer continuing her train of mathematical thoughts.{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=11–12}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=18–24}}{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p= 143}} |

|||

===University of Göttingen=== |

|||

In the spring of 1915, Noether was invited to return to the University of Göttingen by David Hilbert and [[Felix Klein]]. Their effort to recruit her, however, was blocked by the [[Philology|philologists]] and [[historian]]s among the philosophical faculty: women, they insisted, should not become ''[[privatdozent]]''. One faculty member protested: "What will our soldiers think when they return to the university and find that they are required to learn at the feet of a woman?"{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p=14}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=32}}{{Sfn |Osen|1974|pp=144–45}}{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p= 72}} Hilbert responded with indignation, stating, "I do not see that the sex of the candidate is an argument against her admission as ''privatdozent''. After all, we are a university, not a bath house."{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p=14}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=32}}{{Sfn |Osen|1974|pp=144–45}}{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p= 72}} |

|||

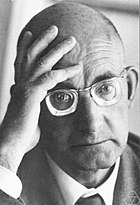

[[File:Hilbert.jpg|thumb|left|upright|In 1915 [[David Hilbert]] invited Noether to join the Göttingen mathematics department, challenging the views of some of his colleagues that a woman should not be allowed to teach at a university.]] |

|||

Noether left for Göttingen in late April; two weeks later her mother died suddenly in Erlangen. She had previously received medical care for an eye condition, but its nature and impact on her death is unknown. At about the same time Noether's father retired and her brother joined the [[German Army (German Empire)|German Army]] to serve in [[World War I]]. She returned to Erlangen for several weeks, mostly to care for her aging father.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 24–26}} |

|||

During her first years teaching at Göttingen she did not have an official position and was not paid; her family paid for her room and board and supported her academic work. Her lectures often were advertised under Hilbert's name, and Noether would provide "assistance". |

|||

Soon after arriving at Göttingen, however, she demonstrated her capabilities by proving the [[theorem]] now known as [[Noether's theorem]], which shows that a [[Conservation law (physics)|conservation law]] is associated with any [[derivative|differentiable]] [[symmetry in physics|symmetry of a physical system]].{{Sfn |Osen|1974|pp=144–45}}{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p=72}} American physicists [[Leon M. Lederman]] and [[Christopher T. Hill]] argue in their book ''Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe'' that Noether's theorem is "certainly one of the most important mathematical theorems ever proved in guiding the development of modern physics, possibly on a par with the [[Pythagorean theorem]]".{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p= 73}} |

|||

[[File:Mathematik Göttingen.jpg|thumb|210px|The mathematics department at the University of Göttingen allowed Noether's ''[[habilitation]]'' in 1919, four years after she had begun lecturing at the school.]] |

|||

When World War I ended, the [[German Revolution of 1918–19]] brought a significant change in social attitudes, including more rights for women. In 1919 the University of Göttingen allowed Noether to proceed with her ''[[habilitation]]'' (eligibility for tenure). Her oral examination was held in late May, and she successfully delivered her ''habilitation'' lecture in June. |

|||

Three years later she received a letter from the [[Prussia]]n Minister for Science, Art, and Public Education, in which he conferred on her the title of ''nicht beamteter ausserordentlicher Professor'' (an untenured professor with limited internal administrative rights and functions{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=188}}). This was an unpaid "extraordinary" professorship, not the higher "ordinary" professorship, which was a civil-service position. Although it recognized the importance of her work, the position still provided no salary. Noether was not paid for her lectures until she was appointed to the special position of ''Lehrbeauftragte für Algebra'' a year later.{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp= 14–18}}{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p=145}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=33–34}} |

|||

===Seminal work in abstract algebra=== |

|||

Although Noether's theorem had a profound effect upon physics, among mathematicians she is best remembered for her seminal contributions to [[abstract algebra]]. In his Introduction to Noether's ''Collected Papers'', [[Nathan Jacobson]] wrote that "The development of abstract algebra, which is one of the most distinctive innovations of twentieth century mathematics, is largely due to her – in published papers, in lectures, and in personal influence on her contemporaries."{{sfn|Noether|1983}} |

|||

Noether's groundbreaking work in algebra began in 1920. In collaboration with W. Schmeidler, she then published a paper about the [[ideal theory|theory of ideals]] in which they defined [[Ideal (ring theory)|left and right ideals]] in a [[ring (mathematics)|ring]]. The following year she published a landmark paper called ''Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen'', analyzing [[ascending chain condition]]s with regard to (mathematical) ideals. Noted algebraist [[Irving Kaplansky]] called this work "revolutionary";{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p=18}} the publication gave rise to the term "[[Noetherian ring]]" and the naming of several other mathematical objects as ''[[Noetherian (disambiguation)|Noetherian]]''.{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p=18}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 44–45}}{{Sfn |Osen|1974|pp=145–46}} |

|||

In 1924 a young Dutch mathematician, [[Bartel Leendert van der Waerden|B. L. van der Waerden]], arrived at the University of Göttingen. He immediately began working with Noether, who provided invaluable methods of abstract conceptualization. Van der Waerden later said that her originality was "absolute beyond comparison".{{Sfn |van der Waerden|1935|p=100}} In 1931 he published ''Moderne Algebra'', a central text in the field; its second volume borrowed heavily from Noether's work. Although Noether did not seek recognition, he included as a note in the seventh edition "based in part on lectures by [[Emil Artin|E. Artin]] and E. Noether".{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=57–58}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p=19}}{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p=74}} She sometimes allowed her colleagues and students to receive credit for her ideas, helping them develop their careers at the expense of her own.{{Sfn |Lederman|Hill|2004|p=74}}{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p=148}} |

|||

Van der Waerden's visit was part of a convergence of mathematicians from all over the world to Göttingen, which became a major hub of mathematical and physical research. From 1926 to 1930 Russian [[topology|topologist]] [[Pavel Alexandrov]] lectured at the university, and he and Noether quickly became good friends. He began referring to her as ''der Noether'', using the masculine German article as a term of endearment to show his respect. She tried to arrange for him to obtain a position at Göttingen as a regular professor, but was only able to help him secure a scholarship from the [[Rockefeller Foundation]].{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=24–25}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=61–63}} They met regularly and enjoyed discussions about the intersections of algebra and topology. In his 1935 memorial address, Alexandrov named Emmy Noether "the greatest woman mathematician of all time".{{Sfn |Alexandrov|1981|pp=100, 107}} |

|||

===Lecturing and students=== |

|||

[[File:EmmyNoether MFO3096.jpg|thumb|left|Noether c. 1930]] |

|||

In Göttingen, Noether supervised more than a dozen doctoral students; her first was [[Grete Hermann]], who defended her dissertation in February 1925. She later spoke reverently of her "dissertation-mother".{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=51}} Noether also supervised [[Max Deuring]], who distinguished himself as an undergraduate and went on to contribute significantly to the field of [[arithmetic geometry]]; [[Hans Fitting]], remembered for [[Fitting's theorem]] and the [[Fitting lemma]]; and [[Zeng Jiongzhi]] (also rendered "Chiungtze C. Tsen" in English), who proved [[Tsen's theorem]]. She also worked closely with [[Wolfgang Krull]], who greatly advanced [[commutative algebra]] with his [[Krull's principal ideal theorem|''Hauptidealsatz'']] and his [[Krull dimension|dimension theory]] for commutative rings.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 53–57}} |

|||

In addition to her mathematical insight, Noether was respected for her consideration of others. Although she sometimes acted rudely toward those who disagreed with her, she nevertheless gained a reputation for constant helpfulness and patient guidance of new students. Her loyalty to mathematical precision caused one colleague to name her "a severe critic", but she combined this demand for accuracy with a nurturing attitude.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=37–49}} A colleague later described her this way: "Completely unegotistical and free of vanity, she never claimed anything for herself, but promoted the works of her students above all."{{Sfn |van der Waerden|1935|p= 98}} |

|||

Her frugal lifestyle at first was due to being denied pay for her work; however, even after the university began paying her a small salary in 1923, she continued to live a simple and modest life. She was paid more generously later in her life, but saved half of her salary to bequeath to her nephew, [[Gottfried E. Noether]].{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 46–48}} |

|||

Mostly unconcerned about appearance and manners, biographers suggest she focused on her studies. A distinguished algebraist [[Olga Taussky-Todd]] described a luncheon, during which Noether, wholly engrossed in a discussion of mathematics, "gesticulated wildly" as she ate and "spilled her food constantly and wiped it off from her dress, completely unperturbed".{{Sfn |Taussky|1981|p=80}} Appearance-conscious students cringed as she retrieved the handkerchief from her blouse and ignored the increasing disarray of her hair during a lecture. Two female students once approached her during a break in a two-hour class to express their concern, but they were unable to break through the energetic mathematics discussion she was having with other students.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 40–41}} |

|||

According to van der Waerden's obituary of Emmy Noether, she did not follow a lesson plan for her lectures, which frustrated some students. Instead, she used her lectures as a spontaneous discussion time with her students, to think through and clarify important cutting-edge problems in mathematics. Some of her most important results were developed in these lectures, and the lecture notes of her students formed the basis for several important textbooks, such as those of van der Waerden and Deuring. |

|||

Several of her colleagues attended her lectures, and she allowed some of her ideas, such as the [[crossed product]] (''verschränktes Produkt'' in German) of associative algebras, to be published by others. Noether was recorded as having given at least five semester-long courses at Göttingen:<ref name="scharlau_49">Scharlau, W. "Emmy Noether's Contributions to the Theory of Algebras" in {{Harvnb|Teicher|1999|p=49}}.</ref> |

|||

* Winter 1924/25: ''Gruppentheorie und hyperkomplexe Zahlen'' (Group Theory and Hypercomplex Numbers) |

|||

* Winter 1927/28: ''Hyperkomplexe Grössen und Darstellungstheorie'' (Hypercomplex Quantities and Representation Theory) |

|||

* Summer 1928: ''Nichtkommutative Algebra'' (Noncommutative Algebra) |

|||

* Summer 1929: ''Nichtkommutative Arithmetik'' (Noncommutative Arithmetic) |

|||

* Winter 1929/30: ''Algebra der hyperkomplexen Grössen'' (Algebra of Hypercomplex Quantities). |

|||

These courses often preceded major publications in these areas. |

|||

Noether spoke quickly—reflecting the speed of her thoughts, many said—and demanded great concentration from her students. Students who disliked her style often felt alienated.{{Sfn |Mac Lane|1981|p=77}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=37}} Some pupils felt that she relied too much on spontaneous discussions. Her most dedicated students, however, relished the enthusiasm with which she approached mathematics, especially since her lectures often built on earlier work they had done together. |

|||

She developed a close circle of colleagues and students who thought along similar lines and tended to exclude those who did not. "Outsiders" who occasionally visited Noether's lectures usually spent only 30 minutes in the room before leaving in frustration or confusion. A regular student said of one such instance: "The enemy has been defeated; he has cleared out."{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 38–41}} |

|||

Noether showed a devotion to her subject and her students that extended beyond the academic day. Once, when the building was closed for a state holiday, she gathered the class on the steps outside, led them through the woods, and lectured at a local coffee house.{{Sfn |Mac Lane|1981|p=71}} Later, after she had been dismissed by the [[Third Reich]], she invited students into her home to discuss their plans for the future and mathematical concepts.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p= 76}} |

|||

===Moscow=== |

|||

[[File:Moscow 05-2012 Mokhovaya 05.jpg|thumb|right|ネーターは1928年から29年の冬の間 [[Moscow State University]] で教えていた。]] |

|||

In the winter of 1928–29 Noether accepted an invitation to [[Moscow State University]], where she continued working with [[Pavel Alexandrov|P. S. Alexandrov]]. In addition to carrying on with her research, she taught classes in abstract algebra and [[algebraic geometry]]. She worked with the topologists, [[Lev Pontryagin]] and [[Nikolai Chebotaryov]], who later praised her contributions to the development of ''[[Galois theory]]''.{{Sfn | Dick |1981|pp=63–64}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p=26}}{{Sfn |Alexandrov|1981|pp= 108–10}} |

|||

Although politics was not central to her life, Noether took a keen interest in political matters and, according to Alexandrov, showed considerable support for the [[Russian Revolution (1917)]]. She was especially happy to see [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] advancements in the fields of science and mathematics, which she considered indicative of new opportunities made possible by the [[Bolshevik]] project. This attitude caused her problems in Germany, culminating in her eviction from a [[Pension (lodging)|pension lodging]] building, after student leaders complained of living with "a Marxist-leaning Jewess".{{Sfn |Alexandrov|1981|pp= 106–9}} |

|||

[[File:Paul S Alexandroff 2.jpg|thumb|140px|{{仮リンク|パヴェル・アレクサンドロフ|en|Pavel Alexandrov}}]] |

|||

Noether planned to return to Moscow, an effort for which she received support from Alexandrov. After she left Germany in 1933 he tried to help her gain a chair at Moscow State University through the [[Narkompros|Soviet Education Ministry]]. Although this effort proved unsuccessful, they corresponded frequently during the 1930s, and in 1935 she made plans for a return to the Soviet Union.{{Sfn |Alexandrov|1981|pp= 106–9}} Meanwhile, her brother, [[Fritz Noether|Fritz]] accepted a position at the Research Institute for Mathematics and Mechanics in [[Tomsk]], in the Siberian Federal District of Russia, after losing his job in Germany.{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p = 150}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=82–83}} |

|||

===Recognition=== |

|||

In 1932 Emmy Noether and [[Emil Artin]] received the [[Ackermann–Teubner Memorial Award]] for their contributions to mathematics.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Noether_Emmy.html | title = Emmy Amalie Noether |accessdate= 4 September 2008 | type = biography | publisher= St And. | location = UK}}</ref> The prize carried a monetary reward of 500 [[German Reichsmark|Reichsmarks]] and was seen as a long-overdue official recognition of her considerable work in the field. Nevertheless, her colleagues expressed frustration at the fact that she was not elected to the [[Göttingen Academy of Sciences|Göttingen ''Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften'']] (academy of sciences) and was never promoted to the position of ''Ordentlicher Professor''{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=72–73}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp= 26–27}} (full professor).{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p = 188}} |

|||

[[File:Zuerich vier Kirchen.jpg|thumb|left|Noether visited [[Zürich]] in 1932 to deliver a [[list of International Congresses of Mathematicians Plenary and Invited Speakers|plenary address at the International Congress of Mathematicians]].]] |

|||

Noether's colleagues celebrated her fiftieth birthday in 1932, in typical mathematicians' style. [[Helmut Hasse]] dedicated an article to her in the ''[[Mathematische Annalen]]'', wherein he confirmed her suspicion that some aspects of [[noncommutative algebra]] are simpler than those of [[commutative algebra]], by proving a noncommutative [[quadratic reciprocity|reciprocity law]].{{Sfn |Hasse|1933|p= 731}} This pleased her immensely. He also sent her a mathematical riddle, the "mμν-riddle of syllables", which she solved immediately; the riddle has been lost.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=72–73}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp= 26–27}} |

|||

In November of the same year, Noether delivered a plenary address (''großer Vortrag'') on "Hyper-complex systems in their relations to commutative algebra and to number theory" at the [[International Congress of Mathematicians]] in [[Zürich]]. The congress was attended by 800 people, including Noether's colleagues [[Hermann Weyl]], [[Edmund Landau]], and [[Wolfgang Krull]]. There were 420 official participants and twenty-one plenary addresses presented. Apparently, Noether's prominent speaking position was a recognition of the importance of her contributions to mathematics. The 1932 congress is sometimes described as the high point of her career.{{Sfn | Kimberling |1981|pp=26–27}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 74–75}} |

|||

===Expulsion from Göttingen=== |

|||

When [[Adolf Hitler]] became the [[Chancellor of Germany (German Reich)|German ''Reichskanzler'']] in January 1933, [[Nazi]] activity around the country increased dramatically. At the University of Göttingen the German Student Association led the attack on the "un-German spirit" attributed to Jews and was aided by a [[privatdozent]] named Werner Weber, a former student of Noether. [[Antisemitism|Antisemitic]] attitudes created a climate hostile to Jewish professors. One young protester reportedly demanded: "Aryan students want Aryan mathematics and not Jewish mathematics."<ref name="kim29">{{Harvnb|Kimberling|1981|p=29}}.</ref> |

|||

One of the first actions of Hitler's administration was the [[Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service]] which removed Jews and politically suspect government employees (including university professors) from their jobs unless they had "demonstrated their loyalty to Germany" by serving in World War I. In April 1933 Noether received a notice from the Prussian Ministry for Sciences, Art, and Public Education which read: "On the basis of paragraph 3 of the Civil Service Code of 7 April 1933, I hereby withdraw from you the right to teach at the University of Göttingen."{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=75–76}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp = 28–29}} Several of Noether's colleagues, including [[Max Born]] and [[Richard Courant]], also had their positions revoked.{{Sfn | Dick |1981|pp=75–76}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp = 28–29}} Noether accepted the decision calmly, providing support for others during this difficult time. [[Hermann Weyl]] later wrote that "Emmy Noether—her courage, her frankness, her unconcern about her own fate, her conciliatory spirit—was in the midst of all the hatred and meanness, despair and sorrow surrounding us, a moral solace."<ref name="kim29"/> Typically, Noether remained focused on mathematics, gathering students in her apartment to discuss [[class field theory]]. When one of her students appeared in the uniform of the Nazi [[paramilitary]] organization ''[[Sturmabteilung]]'' (SA), she showed no sign of agitation and, reportedly, even laughed about it later.{{Sfn |Dick|1981| pp= 75–76}}{{Sfn | Kimberling | 1981 |pp = 28–29}} |

|||

===Bryn Mawr=== |

|||

[[File:Bryn Mawr Sunset.jpg|thumb|right|[[Bryn Mawr College]] provided a welcoming home for Noether during the last two years of her life.]] |

|||

As dozens of newly unemployed professors began searching for positions outside of Germany, their colleagues in the United States sought to provide assistance and job opportunities for them. [[Albert Einstein]] and [[Hermann Weyl]] were appointed by the [[Institute for Advanced Study]] in [[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]], while others worked to find a sponsor required for legal [[immigration]]. Noether was contacted by representatives of two educational institutions, [[Bryn Mawr College]] in the United States and [[Somerville College]] at the [[University of Oxford]] in England. After a series of negotiations with the [[Rockefeller Foundation]], a grant to Bryn Mawr was approved for Noether and she took a position there, starting in late 1933.{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=78–79}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp= 30–31}} |

|||

At Bryn Mawr, Noether met and befriended [[Anna Johnson Pell Wheeler|Anna Wheeler]], who had studied at Göttingen just before Noether arrived there. Another source of support at the college was the Bryn Mawr president, Marion Edwards Park, who enthusiastically invited mathematicians in the area to "see Dr. Noether in action!"{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=32–33}}{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=80}} Noether and a small team of students worked quickly through van der Waerden's 1930 book ''Moderne Algebra I'' and parts of [[Erich Hecke]]'s ''Theorie der algebraischen Zahlen'' (''Theory of algebraic numbers'').{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp= 80–81}} |

|||

In 1934, Noether began lecturing at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton upon the invitation of [[Abraham Flexner]] and [[Oswald Veblen]]. She also worked with and supervised [[Abraham Adrian Albert|Abraham Albert]] and [[Harry Vandiver]].{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp=81–82}} However, she remarked about [[Princeton University]] that she was not welcome at the "men's university, where nothing female is admitted".{{Sfn |Dick | 1981 |p= 81}} |

|||

Her time in the United States was pleasant, surrounded as she was by supportive colleagues and absorbed in her favorite subjects.{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p=151}}{{Sfn|Dick|1981|p=83}} In the summer of 1934 she briefly returned to Germany to see Emil Artin and her brother Fritz before he left for Tomsk. Although many of her former colleagues had been forced out of the universities, she was able to use the library as a "foreign scholar".{{Sfn | Dick|1981|p=82}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p= 34}} |

|||

==死== |

|||

[[File:Bryn Mawr College Cloisters.JPG|thumb|250px|right|Noether's remains were placed under the walkway surrounding the cloisters of Bryn Mawr's [[Bryn Mawr College#M. Carey Thomas Library|M. Carey Thomas Library]].]] |

|||

1935年4月、医者はネーターの[[骨盤]]に[[腫瘍]]を発見した。医者は手術の合併症を心配し、まず2日間ベッドで静養するよう言った。手術中に医者は「大きな[[カンタロープ]]ほどの大きさの」[[卵巣嚢腫]]を発見した{{Sfn |Kimberling| 1981| pp= 37–38}}。彼女の[[子宮]]の2つのより小さい腫瘍は良性であることが分かり手術が長引くのを避けるため除かれなかった。3日間彼女は順調に回復したように見え、4日目の[[循環虚脱]]からすぐに回復した。4月14日彼女は意識を失い、体温は {{convert |109|°F|°C|sigfig=3}} まで上がり、そして死んだ。「ネーター博士に何が起こったのか言うことは簡単ではない」と物理学者の一人は書いた。「ある種の異常な毒性の感染があって温熱中枢がある脳の基底部にダメージを与えたということもありうる。」<!-- |

|||

"[I]t is not easy to say what had occurred in Dr. Noether", one of the physicians wrote. "It is possible that there was some form of unusual and virulent infection, which struck the base of the brain where the heat centers are supposed to be located." |

|||

-->{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp= 37–38}} |

|||

ネーターの死の数日後、彼女の友人と Bryn Mawr の同僚は College President Park の家で小さな追悼式を行った。ヘルマン・ヴァイルと[[リチャード・ブラウアー]]はプリンストンから来て、ホイーラーとタウスキーとともに今はなき同僚について話した。その後数か月、世界中から賛辞の文書が送られ始めた。アルベルト・アインシュタイン<ref>{{cite news|last1=Einstein|first1=Albert|title=THE LATE EMMY NOETHER.; Professor Einstein Writes in Appreciation of a Fellow-Mathematician.|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9807EFDD163CE33ABC4C53DFB366838E629EDE|accessdate=24 March 2015|work=[[The New York Times]]|date=4 May 1935}}</ref>はヴァン・デル・ヴェルデン、ヴァイル、{{仮リンク|パヴェル・アレクサンドロフ|en|Pavel Alexandrov}}とともに敬意を表した。彼女は火葬され、遺灰は Bryn Mawr の [[:en:Bryn Mawr College#M. Carey Thomas Library|M. Carey Thomas Library]] の回廊のまわりの歩道の下に埋葬された{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|p= 39}}。 |

|||

==数学と物理への貢献== |

|||

[[抽象代数学]]と[[トポロジー]]におけるネーターの仕事は数学に大きな影響を与え、また物理においては、[[ネーターの定理]]が[[理論物理学]]と[[力学系]]を広範囲に渡る結果を持つ。彼女は抽象的思考に非常に長けており、数学の問題に新しく独自の方法で取り組むことができた{{Sfn |Osen|1974|pp=148–49}}{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp=11–12}}。彼女の友人であり同僚である[[ヘルマン・ヴァイル]] (Hermann Weyl) は彼女の業績を次のように三つの時代に分けて記述した。 |

|||

{{Quote |エミー・ネーターの科学的業績は次の3つの明確に異なる時代に分かれる。<br /> |

|||

(1) the period of relative dependence, 1907–1919;<br /> |

|||

(2) イデアルの一般論の周辺の研究 1920–1926;<br /> |

|||

(3) 非可換多元環、線型変換によるそれらの表現、可換数体やその数論の研究へのその応用、の研究。|{{Harvnb |Weyl| 1935}}}} |

|||

第一の時代 (1907–19) には、ネーターは、{{仮リンク|不変式論|label=微分的・代数的不変量|en|invariant theory}}を主に研究しており、これは {{仮リンク|Paul Gordan|en|Paul Gordan}} の下での学位論文に始まっていた。彼女の数学的地平線は広がり、Her mathematical horizons broadened, and her work became more general and abstract, as she became acquainted with the work of [[David Hilbert]], through close interactions with a successor to Gordan, [[Ernst Sigismund Fischer]]. 1915年にゲッティンゲンに移ってから、彼女は物理学に影響の大きい仕事、2つの[[ネーターの定理]]を成し遂げた。 |

|||

第二の時代 (1920–26) には、ネーターは数学の[[環 (数学)|環]]の理論の発展に身を捧げた{{Sfn |Gilmer|1981|p= 131}}。 |

|||

第三の時代 (1927–35) には、ネーターは{{仮リンク|非可換環論|en|noncommutative algebra}}、[[線型写像|線型変換]]、可換数体に焦点を当てた{{Sfn |Kimberling|1981|pp= 10–23}}。 |

|||

===歴史的文脈=== |

|||

1832年から1935年のネーターの死までの時代、数学の分野、特に[[代数学]]、は格段に進歩し、その残響は今なお感じられる。その前の時代の数学は、特定の型の方程式、例えば[[三次関数|三次]]、[[四次方程式|四次]]、[[五次方程式]]、を解くための実際的な手法や、[[1の冪根|それに関連した]]、[[コンパスと定規による作図|コンパスと定規]]を用いて[[正多角形]]を作図する問題を研究していた。5 のような[[素数]]は[[ガウスの整数]]で[[素因数分解|分解]]できるという[[カール・フリードリッヒ・ガウス]]の1832年の証明<ref>C. F. Gauss, Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum. Commentatio secunda., Comm. Soc. Reg. Sci. Göttingen 7 (1832) 1-34; reprinted in Werke, Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim, 1973, pp. 93–148.</ref>、[[エヴァリスト・ガロワ]]の1832年の[[置換群]]の導入(彼の死のために彼の論文は1846年になってリューヴィルによって出版されたのであるが)、[[ウィリアム・ローワン・ハミルトン]]の1843年の[[四元数]]の発見、[[アーサー・ケイリー]]の1854年の群のより現代的な定義、に始まり、研究はより普遍的な規則によって定義されたより抽象的な対象の性質を決定するようになった。ネーターの数学への最も重要な貢献はこの新しい分野、[[抽象代数学]]の発展への貢献であった<ref name="algebra_contributions_paramount">G.E. {{Harvnb|Noether|1987|p=168}}.</ref>。 |

|||

====抽象代数学と ''begriffliche Mathematik'' (conceptual mathematics)==== |

|||

抽象代数学における最も基本的な対象のうちの2つは[[群 (数学)|群]]と[[環 (数学)|環]]である。 |

|||

''群''は元の集合と1つの演算からなる。演算は第一の元と第二の元から第三の元を与える。演算は群となるためにある条件を満たさねばならない。その条件は、演算が[[閉性|閉じていること]](集合の任意の2元に対し、それらから得られる元も集合の元でなければならない)、[[結合律|結合的]]であること、[[単位元]](任意の元と演算したときにもとのままである(例えば数に 0 を足したり 1 を掛けたりしたときのように)ような元)を持つこと、そして、任意の元に対し[[逆元]]があること、である。 |

|||

''環''は同様に元の集合と、今度は''2つの''演算からなる。1つめの演算により集合は群になり、2つ目の演算は結合的かつ1つ目の演算に対し[[分配則|分配的]]である。2つ目の[[可換性|可換]]であってもなくてもよい。可換であるとは、第一の元と第二の元に演算を施しても第二の元と第一の元に演算を施しても同じ結果になる、つまり元の順序が問題にならないということである。0 でないすべての元 ''a'' が[[乗法逆元]](''ax'' = ''xa'' = 1 なる元 ''x'')をもつとき、環は[[可除環]]と呼ばれる。([[可換体|可換]])[[体 (数学)|体]]は可換な可除環として定義される。 |

|||

群はしばしば''[[群の表現]]''を通して研究される。最も一般的な形では、それは1つの群、1つの集合、そしてその群の集合への''作用''からなる。作用とは、群の元と集合の元から集合の元を得る演算である。ほとんどの場合、集合は[[ベクトル空間]]で、群はベクトル空間の対称性を表す。例えば、空間の rigid な回転を表す群がある。これは空間の対称性の一種である、なぜならば空間は回転されたとき空間の中の物体の位置は変わるかもしれないが空間自身は変わらないからである。ネーターは物理学における不変量に関する彼女の研究においてこの種の対称性を用いた。 |

|||

環を研究する強力な方法の1つはその[[環上の加群|''加群'']]を用いることである。加群は、1つの環と、1つの集合、これは環の台集合とは異なることが多く加群の台集合と呼ばれる、と、加群の台集合の元の対に対する演算と、環の元と加群の元から加群の元を得る演算からなる。加群の台集合とその演算は群をなす。加群は群の表現の環論版である:第二の環の演算と加群の元の対の演算を無視すれば群の表現が決定される。加群の真の有用性は存在する加群の種類と相互作用が環自身からは明白ではない方法で環の構造を明らかにすることにある。これの重要な特別な場合は[[体上の多元環|多元環(代数)]]である。(代数という単語は数学の主題である代数学とその代数学で研究されるある対象の両方を意味する。)多元環は、2つの環と、各環の1つずつの元から第二の環の元を得る演算からなる。この演算により第二の環は第一の環上の加群となる。しばしば第一の環は体である。 |

|||

Words such as "element" and "combining operation" are very general, and can be applied to many real-world and abstract situations. Any set of things that obeys all the rules for one (or two) operation(s) is, by definition, a group (or ring), and obeys all theorems about groups (or rings). Integer numbers, and the operations of addition and multiplication, are just one example. For example, the elements might be [[Word (data type)|computer data words]], where the first combining operation is [[exclusive or]] and the second is [[logical conjunction]]. Theorems of abstract algebra are powerful because they are general; they govern many systems. It might be imagined that little could be concluded about objects defined with so few properties, but precisely therein lay Noether's gift: ''to discover the maximum that could be concluded from a given set of properties, or conversely, to identify the minimum set, the essential properties responsible for a particular observation''. Unlike most mathematicians, she did not make abstractions by generalizing from known examples; rather, she worked directly with the abstractions. As van der Waerden recalled in his obituary of her,{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p= 101}} |

|||

{{quote |The maxim by which Emmy Noether was guided throughout her work might be formulated as follows: "Any relationships between numbers, functions, and operations become transparent, generally applicable, and fully productive only after they have been isolated from their particular objects and been formulated as universally valid concepts."}} |

|||

This is the ''begriffliche Mathematik'' (purely conceptual mathematics) that was characteristic of Noether. This style of mathematics was consequently adopted by other mathematicians, especially in the (then new) field of abstract algebra. |

|||

=====環の例としての整数===== |

|||

[[整数]]の全体は可換環をなす。元は整数で、演算は通常の加法と乗法である。任意の2つの整数を[[加法|足したり]][[乗法|掛けたり]]でき、その結果は整数である。第一の演算、加法は、[[可換]]である、すなわち、環の任意の元 ''a'', ''b'' に対し、''a'' + ''b'' = ''b'' + ''a'' である。第二の演算、乗法も、可換である。しかしこれは他の環では正しい必要はない、つまり、''a'' combined with ''b'' might be different from ''b'' combined with ''a''. Examples of noncommutative rings include [[matrix (mathematics)|matrices]] and [[quaternion]]s. The integers do not form a division ring, because the second operation cannot always be inverted; there is no integer ''a'' such that 3 × ''a'' = 1. |

|||

整数の全体はすべての可換環では成り立たない性質を持っている。重要な例は[[算術の基本定理]]で、任意の正整数は[[素数]]の積に一意的に分解できる。一意的な分解は他の環では必ずしも存在しないが、ネーターは多くの環の[[イデアル]]に対して、今では''{{仮リンク|ラスカー・ネーターの定理|en|Lasker–Noether theorem}}''と呼ばれる一意分解の定理を発見した。ネーターの仕事の多くはMuch of Noether's work lay in determining what properties ''do'' hold for all rings, in devising novel analogs of the old integer theorems, and in determining the minimal set of assumptions required to yield certain properties of rings. |

|||

===第一の時代 (1908–19)=== |

|||

====代数的不変式論==== |

|||

[[File:Emmy Noether - Table of invariants 2.jpg|thumb|250px|right|不変式論に関するネーターの学位論文 {{Sfn | Noether | 1908}} の Table 2. This table collects 202 of the 331 invariants of ternary biquadratic forms. These forms are graded in two variables ''x'' and ''u''. The horizontal direction of the table lists the invariants with increasing grades in ''x'', while the vertical direction lists them with increasing grades in ''u''.]] |

|||

ネーターの経歴の第一の時代における研究の多くは{{仮リンク|不変式論|en|invariant theory}}、主に{{仮リンク|代数的不変式論|en|algebraic invariant theory}}、と関係している。不変式論は変換の[[群 (数学)|群]]の下で変わらないままの(不変な)式に関心がある。日常的な例としては、固いものさしを回転すると、その端点の座標 (''x''<sub>1</sub>, ''y''<sub>1</sub>, ''z''<sub>1</sub>) と (''x''<sub>2</sub>, ''y''<sub>2</sub>, ''z''<sub>2</sub>) は変わるが、公式 {{nowrap|1=''L''<sup>2</sup> = Δ''x''<sup>2</sup> + Δ''y''<sup>2</sup> + Δ''z''<sup>2</sup>}} によって与えられるその長さ ''L'' は同じままである。不変式論は19世紀後半の研究の活発な領域であり、1つには[[フェリックス・クライン]] (Felix Klein) の[[エルランゲン・プログラム]]によって駆り立てられた。それによると、異なるタイプの[[幾何学]]は変換の下での不変量、例えば[[射影幾何学]]の{{仮リンク|複比|en|cross-ratio}}、によって特徴づけられるべきである。不変量の{{仮リンク|archetype|en|archetype|label=archetypal}}な例は二変数に次形式 ''Ax''<sup>2</sup> + ''Bxy'' + ''Cy''<sup>2</sup> の[[判別式]] ''B''<sup>2</sup> − 4''AC'' である。これが不変量と呼ばれるのは、線型な置き換え ''x''→''ax'' + ''by'', ''y''→''cx'' + ''dy'' で行列式 ''ad'' − ''bc'' が 1 であるものによって変わらないからである。このような変換の全体は[[特殊線型群]] ''SL''<sub>2</sub> をなす。(すべての可逆な線型変換からなる[[一般線型群]]のもとで不変な量は(0 を除いて)存在しない、なぜならばこれらの変換はスケール因子を掛けることを含むからである。救済策として、古典的な不変式論はスケール因子の違いを除いて不変な形式である''相対不変量''も考えた。)''SL''<sub>2</sub> の作用によって変わらない ''A'', ''B'', ''C'' のすべての多項式を求めることができる。これらは二変数二次形式の不変量と呼ばれ、判別式の多項式であることが分かる。より一般に、高次の[[斉次多項式]] ''A''<sub>0</sub>x<sup>''r''</sup>''y''<sup>0</sup> + ... + ''A''<sub>''r''</sub>x<sup>0</sup>''y''<sup>''r''</sup> の不変量を求めることができる。それは ''A''<sub>0</sub>, ..., ''A''<sub>''r''</sub> を係数とするある多項式である。さらに一般に、2つよりも多い変数の斉次多項式に対して同様の問いをたてることができる。 |

|||

不変式論の主な目標の1つは "finite basis problem" を解くことだった。任意の2つの不変量の和や積は不変量であり、finite basis problem はすべての不変量は''生成元''と呼ばれる有限個の不変量のリストから始めて得ることができるかどうかを問うた。例えば、判別式は二元二次形式の不変量の(1つの元からなる) finite basis を与える。ネーターの指導教官パウル・ゴルダン (Paul Gordan) は「不変式論の王」("king of invariant theory") として知られていて、彼の数学への主要な貢献は1870年に2変数の斉次多項式の不変式に対して finite basis problem を解いたことだった{{Sfn |Noether|1914|p=11}}{{Sfn |Gordan| 1870}}。彼はこれをすべての不変式とそれらの生成元を見つける構成的な方法を与えることによって証明したが、3変数あるいはそれより多い変数のときにこの構成的なアプローチを遂行することは出来なかった。1890年、ダフィット・ヒルベルト (David Hilbert) は任意個の変数の斉次多項式の不変式に対する同様の主張を証明した{{Sfn | Weyl | 1944|pp = 618–21}}{{Sfn |Hilbert|1890|p= 531}}。さらに、彼の手法は、特殊線型群だけでなく、[[特殊直交群]]のような部分群のいくつかに対しても有効なものであった{{Sfn |Hilbert | 1890 | p = 532}}。彼の最初の証明はいくらか論争を引き起こした、なぜならば生成元を構成する手法を与えていなかったからである、しかしながら後の研究によって彼は彼の手法を構成的にした。ネーターは学位論文でゴルダンの計算的証明を3変数の斉次多項式に拡張した。ネーターの構成的なアプローチにより不変式の間の関係を研究することができるようになった。後に、彼女がより抽象的な手法に転換した後、ネーターは彼女の論文を ''[[wikt:Mist#German|Mist]]'' (がらくた) and ''Formelngestrüpp'' (方程式のジャングル) と呼んだ。 |

|||

====ガロワ理論==== |

|||

[[ガロワ理論]]は方程式の根を[[置換]]する[[可換体|数体]]の変換と関係する。変数 ''x'' の ''n'' [[多項式の次数|次]]の多項式方程式を考えよう。係数はある[[基礎体]]からとられる。例えば、[[実数]]体とか、[[有理数]]体、7 を[[合同算術|法とした]][[有限体|整数]]、など。この多項式の値が 0 になるような ''x'' はあるかもしれないしないかもしれない。もし存在すれば、それは[[多項式の根|根]]と呼ばれる。多項式が ''x''<sup>2</sup> + 1 で体が実数体ならば、多項式は根を持たない、なぜならば ''x'' をどのようにとっても多項式の値は 1 以上になるからである。しかしながら、体が[[体の拡大|拡大]]されると、多項式は根を持ち得、十分に拡大されれば、必ず次数に等しい個数の根を持つ。前の例を続ければ、体が複素数体に拡大されれば、多項式は 2 つの根 ''i'' と −''i'' を得る。ここに ''i'' は[[虚数単位]]、すなわち、{{nowrap|1=''i''<sup> 2</sup> = −1}} を満たす数である。より一般に、多項式が根に分解するような拡大体を多項式の[[分解体]]と呼ぶ。 |

|||

多項式の[[ガロワ群]]は分解体の変換であって基礎体と多項式の根を保つようなものすべてからなる集合である。(数学用語ではこれらの変換は[[自己同型]]と呼ばれる。){{math|''x''<sup>2</sup> + 1}} のガロワ群は2つの元からなる。すべての複素数を自分自身に送る恒等変換と、{{mvar|i}} を {{math|−''i''}} に送る[[複素共役]]写像である。ガロワ群は基礎体を変えないから、多項式の係数は変わらないままであり、したがってすべての根の集合も変わらないままである。しかしながら各根が別の根に動くことは出来、したがって変換は {{mvar|n}} 個の根のその中での[[置換|入れ替わり]]を決定する。ガロワ理論の重要性は[[ガロワ理論の基本定理]]から生ずる。これは基礎体と分解体の間にある体たちはガロワ群の[[部分群]]たちと一対一に対応しているというものである。 |

|||

1918年、ネーターは[[逆ガロワ問題]]に関する影響力の大きい論文を出版した<ref>{{harvnb|Noether|1918}}.</ref>。与えられた体とその拡大の変換のガロワ群を決定する代わりに、ネーターは、体と群が与えられたとき、その体の拡大であって与えられた群をガロワ群として持つものを見つけることが常に可能かどうかを問うた。彼女はこれを「{{仮リンク|ネーターの問題|en|Noether's problem}}」に帰着した。これは体 {{nowrap|''k''(''x''<sub>1</sub>, ... , ''x''<sub>''n''</sub>)}} に作用する[[対称群|置換群]] ''S''<sub>''n''</sub> の部分群 ''G'' の固定体が常に体 ''k'' の純[[超越拡大]]になるかを問うものである。(彼女は1913年の論文で最初にこの問題を述べた<ref>{{harvnb|Noether|1913}}.</ref>。彼女はその問題を同僚の[[エルンスト・フィッシャー]]によるものとしている。)彼女はこれが {{nowrap|1=''n'' = 2}}, 3, 4 に対し正しいことを示した。1969年、{{仮リンク|R. G. Swan|en|R. G. Swan}} は {{nowrap|1=''n'' = 47}} と ''G'' が位数 47 の[[巡回群]]のときにネーターの問題の反例を見つけた<ref>{{harvnb|Swan|1969|p=148}}.</ref>(この群は他の方法で有理数体上の[[ガロワ群]]として実現できるのであるが)。逆ガロワ問題は今なお解かれていない<ref>{{Harvnb|Malle|Matzat|1999}}.</ref>。 |

|||

====物理学==== |

|||

{{main|ネーターの定理|保存則|{{仮リンク|Constant of motion|en|Constant of motion}}}} |

|||

Noether was brought to [[Göttingen]] in 1915 by David Hilbert and Felix Klein, who wanted her expertise in invariant theory to help them in understanding [[general relativity]], a geometrical theory of [[gravitation]] developed mainly by [[Albert Einstein]]. Hilbert had observed that the [[conservation of energy]] seemed to be violated in general relativity, because gravitational energy could itself gravitate. Noether provided the resolution of this paradox, and a fundamental tool of modern [[theoretical physics]], with [[Noether's theorem|Noether's first theorem]], which she proved in 1915, but did not publish until 1918.<ref>{{harvnb|Noether|1918b}}</ref> She not only solved the problem for general relativity, but also determined the conserved quantities for ''every'' system of physical laws that possesses some continuous symmetry. |

|||

Upon receiving her work, Einstein wrote to Hilbert: "Yesterday I received from Miss Noether a very interesting paper on invariants. I'm impressed that such things can be understood in such a general way. The old guard at Göttingen should take some lessons from Miss Noether! She seems to know her stuff."<ref>{{Harvnb|Kimberling|1981|p=13}}.</ref> |

|||

説明のため、ある物理系が、空間にどのように入っているかによらずに同じように振る舞うならば、それを統制する物理法則は回転対称性を持つ。この対称性から、ネーターの定理は形の[[角運動量]]が保存されなければならないことを示している<ref name="ledhill">{{Harvnb|Lederman|Hill|2004|pp=97–116}}.</ref>。物理系自身は対象である必要はない。宇宙を漂っているぎざぎざの小惑星はその非対称性にもかかわらず[[角運動量保続則|角運動量を保存する]]。むしろ、系を統制する''物理法則''の対称性は保存則の原因である。別の例として、ある物理実験がどんな場所でもどんな時間でも同じ結果になるならば、その法則は空間と時間の連続変換の下で対称性を持つ。ネーターの定理により、これらの対称性はこの系においてそれぞれ[[線型運動量]]と[[エネルギー]]の[[保存則]]を説明する。 |

|||

ネーターの定理は現代[[理論物理学]]の基本的な道具となっている。それはそれが保存則に与える洞察のためでもあるし、また実際的な計算の道具としてでもある<ref name="neeman_1999">。[[Yuval Ne'eman|Ne'eman, Yuval]]. "The Impact of Emmy Noether's Theorems on XX1st Century Physics", {{Harvnb|Teicher|1999|pp=83–101}}.</ref> 彼女の定理によって研究者は物理系の観察された対称性から保存量を決定することができる。逆に、それは仮説的物理法則のクラスに基づいた物理系の記述を容易にする。説明のため、新しい物理現象が発見されたとしよう。ネーターの定理は現象の理論的モデルの判定法を提供する。理論が連続的対称性を持つならば、ネーターの定理は保存量を持つことを保証する。そして理論が正しいためには、この保存が実験で観測できなければならない。 |

|||

===第二の時代 (1920–26)=== |

|||

ネーターの第一の時代の結果は印象的かつ有用ではあるものの、彼女の数学者としての名声は、ヘルマン・ヴァイルと B. L. ファン・デル・ヴェルデンによって彼女の obituary において書かれているように、彼女の第二・第三時代に彼女がしたパイオニア的仕事により基づいている。 |

|||

これらの時代において、彼女は単にそれ以前の数学者のアイデアや手法を適用しただけではない。むしろ、彼女は将来の数学者によって使われる新しい数学の定義を作っていた。特に、彼女は先の[[リヒャルト・デデキント]] (Ricahrd Dedekind) の仕事を一般化して、[[環 (数学)|環]]の[[イデアル]]の全く新しい理論を展開した。彼女はまた昇鎖条件を展開したことでも名高い。これは単純な有限性の条件で、彼女の手により強力な結果が得られた。そのような条件とイデアルの理論によってネーターは多くの以前の結果を一般化し、彼女の父によって研究されていた{{仮リンク|除去理論|en|elimination theory}}や[[代数多様体]]のような、古い問題を新しい観点から扱うことができた。 |

|||

====昇鎖条件と降鎖条件==== |

|||

この時代、ネーターは昇鎖条件 (''Teilerkettensatz'') や降鎖条件 (''Vielfachenkettensatz'') を巧みに用いたことで有名になった。[[集合 (数学)|集合]] ''S'' の[[空集合|空でない]][[部分集合]]の列 ''A''<sub>1</sub>, ''A''<sub>2</sub>, ''A''<sub>3</sub>, ... は、各部分集合が次の部分集合の部分集合になっている |

|||

:<math>A_{1} \subset A_{2} \subset A_{3} \subset \cdots</math> |

|||

ときに通常 ''ascending'' と言われる。 |

|||

逆に、''S'' の部分集合の列が ''descending'' とは、各部分集合が次の部分集合を含む |

|||

:<math>A_{1} \supset A_{2} \supset A_{3} \supset \cdots</math> |

|||

ことをいう。 |

|||

鎖はある ''n'' が存在してすべての ''m'' ≥ ''n'' に対して ''A''<sub>''n''</sub> = ''A''<sub>''m''</sub> となるようなとき''有限個のステップの後停留的になる''という。与えられた集合の部分集合の集まりが[[昇鎖条件]]を満たすとは、任意の昇鎖列が有限個のステップの後停留的になることをいう。降鎖条件を満たすとは任意の降鎖列が有限個のステップの後停留的になることをいう。 |

|||

昇鎖条件や降鎖条件は、多くの種類の数学的対象に適用できるという意味で、一般的であり、一見すると、それほど強力には思われないかもしれない。しかしながら、ネーターはそのような条件を最大限に生かす方法を示した。例えば、それらを使って部分対象のすべての集合は極大/極小元を持つこととか複雑な対象が少ない個数の元によって生成できることとかを示す方法である。これらの結論はしばしば証明の重要なステップである。 |

|||

[[抽象代数学]]の対象の多くの種類は鎖条件を満たすことができ、通常それらが昇鎖条件を満たすときそれらは彼女に敬意を表して{{仮リンク|ネーター的|label=''ネーター''(''的'')|en|Noetherian (disambiguation)}}と呼ばれる。定義により、[[ネーター環]]はその左と右イデアルに対し昇鎖条件を満たし、{{仮リンク|ネーター群|en|Noetherian group}}は部分群の任意の真の昇鎖が有限である群である。[[ネーター加群]]は部分加群の任意の真の昇鎖が有限個のステップでとまる[[環上の加群|加群]]である。[[ネーター空間]]は開部分空間の任意の真の昇鎖が有限個のステップの後にとまる[[位相空間]]であり、この定義によりネーター[[環のスペクトル]]はネーター位相空間となる。 |

|||

鎖条件はしばしば部分対象にも「引き継がれる」。例えば、ネーター空間のすべての部分空間はそれ自身ネーターであり、ネーター群のすべての部分群や商群もネーターであり、{{仮リンク|mutatis mutandis|en|mutatis mutandis|label=必要な変更を加えて}}同じことがネーター加群の部分加群と商加群に対して成り立つ。ネーター環のすべての商環はネーターであるが、部分環は必ずしもそうでない。鎖条件はまたネーター的対象の組み合わせや拡大に対しても引き継がれることがある。例えば、ネーター環の有限直和はネーターであり、ネーター環上の形式[[冪級数]]環もネーターである。 |

|||

そのような鎖条件の別の応用は、[[数学的帰納法]]の一般化である[[ネーター帰納法]]([[整礎帰納法]]とも呼ばれる)にある。それはしばしば対象の集まりについての一般的なステートメントをその集まりの特定の対象についてのステートメントに帰着するために使われる。''S'' を[[半順序集合]]としよう。''S'' の対象についての主張を証明する1つの方法は[[反例]]の存在を仮定し矛盾を導くことによってもとの主張の[[対偶]]を証明することである。ネーター帰納法の基本的な前提は ''S'' の任意の空でない部分集合は極小元を持つことである。特に、すべての反例の集合は極小元、''極小の反例''を含む。したがって、もとの主張を証明するためには、表面上はるかに弱い何か:任意の反例に対してより小さい反例が存在することを証明すれば十分である。 |

|||

====可換環、イデアル、加群==== |

|||

ネーターの論文 ''Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen'' (''Theory of Ideals in Ring Domains'', 1921),{{Sfn | Noether | 1921}} は一般の可換環論の基礎であり、[[可換環]]の最初の一般的な定義の1つを与えている<ref name="Gil133"/>。彼女の論文以前は、可換代数のほとんどの結果は体上の多項式環や代数的整数の環のような可換環の特別な例に制限されていた。ネーターは[[イデアル]]の昇鎖条件を満たす環ではすべてのイデアルが有限生成であることを証明した。1943年、フランス人数学者[[クロード・シュヴァレー]] (Claude Chevalley) はこの性質を記述するために[[ネーター環]]という用語を提唱した<ref name="Gil133">{{Harvnb|Gilmer|1981|p=133}}.</ref>。ネーターの1921年の主要な結果は'''{{仮リンク|ラスカー・ネーターの定理|en|Lasker–Noether theorem}}'''である。これは多項式環のイデアルの準素分解に関するラスカーの定理をすべてのネーター環に拡張するものである。ラスカー・ネーターの定理は任意の正整数は[[素数]]の積として表すことができその分解は一意的であるという[[算術の基本定理]]の一般化と見ることができる。 |

|||

ネーターの仕事 ''Abstrakter Aufbau der Idealtheorie in algebraischen Zahl- und Funktionenkörpern'' (''代数的数におけるイデアル論の抽象的構造と関数体'', 1927)<ref>{{harvnb|Noether|1927}}.</ref>は任意のイデアルが素イデアルへの一意的な分解を持つような環を[[デデキント整域]]、すなわちネーターかつ 0 または 1 [[クルル次元|次元]]かつ商体において[[整閉]]であるような整域として特徴づけた。この論文はまた今では[[同型定理]]と呼ばれるもの、これはある基本的な[[自然同型]]を記述するものである、やネーター加群や[[アルティン加群]]に関するいくつかの他の基本的な結果も含んでいる。 |

|||

====除去理論==== |

|||

1923年から24年、ネーターは彼女のイデアル論を{{仮リンク|除去理論|en|elimination theory}}に適用し(彼女が彼女の学生 Kurt Hentzelt に帰した定式化において)、{{仮リンク|多項式の分解|en|polynomial factorization}}についての基本定理を直接持ち越すことができることを示した{{Sfn |Noether|1923}}{{Sfn |Noether|1923b}}{{Sfn |Noether | 1924}}。伝統的に、除去理論は多項式方程式の系から1つあるいはそれ以上の変数を、通常は[[終結式]]の手法によって、除去することに関心がある。説明のため、方程式系はしばしば(変数 ''x'' を忘れた)行列 ''M'' 掛ける(''x'' の異なる冪のみを持つ)ベクトル ''v'' イコール零ベクトル、{{nowrap|1=''M''•''v'' = 0}}, の形に書ける。したがって、行列 ''M'' の[[行列式]]は 0 でなければならず、変数 ''x'' が除去される新しい方程式を得る。 |

|||

====有限群の不変式論==== |

|||

finite basis problem のヒルベルトのもともとの非構成的解法のようなテクニックは群作用の不変量についての量的な情報を得るために使うことは出来ず、さらに、それらはすべての群作用には適用しなかった。ネーターは1915年の論文{{Sfn | Noether| 1915}}において、標数 0 の体上の有限次元ベクトル空間に作用する有限変換群 ''G'' に対して finite basis problem の解法を見つけた。彼女の解法は不変式環は斉次不変式であってその次数が有限群の位数以下であるようなもの(の一部)によって生成されることを示している。これは '''Noether's bound'''(ネーターの上界)と呼ばれる。彼女の論文は Noether's bound の2つの証明を与え、どちらの証明も体の標数が |''G''|!, 群 ''G'' の位数 |''G''| の[[階乗]]、と[[互いに素]]なときにも有効である。生成元の次数は体の標数が |''G''| を割り切るときには Noether's bound を満たす必要はないが{{Sfn |Fleischmann | 2000 |p = 24}}、ネーターはこの bound が体の標数が |''G''| ではなく |''G''|! を割り切るときに正しいかどうかを決定することはできなかった。長年の間この特定の場合に対するこの bound の真偽を決定することは "Noether's gap" と呼ばれる未解決問題であった。最終的に2000年に Fleischmann と 2001 年に Fogarty によって独立に解かれた。両者とも bound は正しいままであることを示した{{Sfn |Fleischmann|2000|p=25}}{{Sfn | Fogarty |2001|p=5}}。 |

|||

ネーターは1926年の論文{{Sfn |Noether|1926}}においてヒルベルトの定理を任意の体上の有限群の表現に拡張した。ヒルベルトの仕事から従わない新しい場合は体の標数が群の位数を割り切るときである。ネーターの結果は後に {{仮リンク|William Haboush|en|William Haboush}} によって{{仮リンク|Haboush's theorem|en|Haboush's theorem|label=マンフォード予想}}の彼の証明によってすべての簡約群へと拡張された{{Sfn |Haboush|1975}}。この論文においてネーターは''{{仮リンク|ネーターの正規化定理|en|Noether normalization lemma}}''の導入もした。これは体 ''k'' 上の有限生成[[整域]] ''A'' は[[代数的に独立]]な元の集合 {{nowrap|''x''<sub>1</sub>, ... , ''x''<sub>''n''</sub>}} であって ''A'' が {{nowrap |''k''[''x''<sub>1</sub>, ... , ''x''<sub>''n''</sub>]}} 上[[整元|整]]であるものをもつというものである。 |

|||

====トポロジーへの貢献==== |

|||

[[File:Mug and Torus morph.gif|thumb|right|250px|コーヒーカップのドーナツ([[トーラス]])への連続変形([[ホモトピー]])と逆]] |

|||

{{仮リンク|パヴェル・アレクサンドロフ|en|Pavel Alexandrov}}と[[ヘルマン・ヴァイル]]が死亡記事に書いたように、ネーターの[[位相幾何学]]への貢献は彼女のアイデアの惜しみなさと彼女の洞察がいかに数学の全分野を変えたかを例証する。位相幾何学では数学者は変形のもとでも不変なままな対象の性質、例えば[[連結空間|連結性]]、を研究する。よくあるジョークは、位相幾何学者はドーナツとコーヒーカップを区別できないというものである。互いに連続的に変形できるからである。 |

|||

Noether is credited with fundamental ideas that led to the development of [[algebraic topology]] from the earlier [[combinatorial topology]], specifically, the idea of [[Homology theory#Towards algebraic topology|homology group]]s.{{Sfn |Hilton|1988|p=284}} According to the account of Alexandrov, Noether attended lectures given by [[Heinz Hopf]] and by him in the summers of 1926 and 1927, where "she continually made observations which were often deep and subtle"{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=173}} and he continues that, |

|||

{{quote |When... she first became acquainted with a systematic construction of combinatorial topology, she immediately observed that it would be worthwhile to study directly the [[group (mathematics)|groups]] of algebraic complexes and cycles of a given polyhedron and the [[subgroup]] of the cycle group consisting of cycles homologous to zero; instead of the usual definition of [[Betti number]]s, she suggested immediately defining the Betti group as the [[quotient group|complementary (quotient) group]] of the group of all cycles by the subgroup of cycles homologous to zero. This observation now seems self-evident. But in those years (1925–28) this was a completely new point of view.{{Sfn | Dick | 1981|p= 174}}}} |

|||

Noether's suggestion that topology be studied algebraically was adopted immediately by Hopf, Alexandrov, and others,{{Sfn | Dick | 1981|p= 174}} and it became a frequent topic of discussion among the mathematicians of Göttingen.<ref name = Hirzebruch>[[Friedrich Hirzebruch|Hirzebruch, Friedrich]]. "Emmy Noether and Topology" in {{Harvnb |Teicher|1999|pp=57–61}}.</ref> Noether observed that her idea of a [[Betti group]] makes the [[Euler characteristic|Euler–Poincaré formula]] simpler to understand, and Hopf's own work on this subject{{Sfn |Hopf|1928}} "bears the imprint of these remarks of Emmy Noether".{{Sfn |Dick|1981|pp = 174–75}} Noether mentions her own topology ideas only as an aside in a 1926 publication,{{Sfn |Noether | 1926b}} where she cites it as an application of [[group theory]].<ref>Hirzebruch, Friedrich, "Emmy Noether and Topology" in {{Harvnb | Teicher|1999|p= 63}}.</ref> |

|||

This algebraic approach to topology was also developed independently in [[Austria]]. In a 1926–27 course given in [[Vienna]], [[Leopold Vietoris]] defined a [[homology group]], which was developed by [[Walther Mayer]], into an axiomatic definition in 1928.<ref>Hirzebruch, Friedrich, "Emmy Noether and Topology" in {{Harvnb |Teicher|1999 | pp = 61–63}}.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Helmut Hasse.jpg|thumb|upright|left|[[ヘルムート・ハッセ]]はネーターや他の数学者と研究して[[中心単純環]]の理論を基礎づけた。]] |

|||

===第三の時代 (1927–35)=== |

|||

====超複素数と表現論==== |

|||

[[超複素数]]と[[群の表現]]の多くの研究は19世紀と20世紀初頭になされたが、共通点は無かった。ネーターはこれらの結果を統合し、群と多元環の初めての一般的な表現論を与えた<ref name="noether_1929">{{harvnb|Noether|1929}}.</ref>。手短に言えば、ネーターは[[結合多元環]]の構造論と群の表現論を包摂して、[[昇鎖条件]]を満たす[[環 (数学)|環]]の[[環上の加群|加群]]と[[イデアル]]の1つの数学的理論にした。ネーターのこの1つの仕事は現代代数学の発展に基本的で重要なものであった<ref name="vdWaerden_1985" >{{harvnb|van der Waerden|1985|p = 244}}.</ref>。 |

|||

====非可換多元環==== |

|||

ネーターはまた代数学の分野の他のいくつかの進展にも貢献している。[[エミール・アルティン]] (Emil Artin)、[[リチャード・ブラウアー]] (Richard Brauer)、[[ヘルムート・ハッセ]] (Helmut Hasse) とともに、ネーターは[[中心的単純環|中心的単純多元環]]の理論を構築した{{Sfn |Lam | 1981 | pp= 152–53}}。 |

|||

ネーター、ヘルムート・ハッセ、[[リチャード・ブラウアー]]による影響力の大きい論文に、除法が可能な代数系である[[可除多元環]]を扱ったものがある<ref name = "hasse_1932">{{harvnb |Brauer|Hasse|Noether|1932}}.</ref>。彼らは次の2つの重要な定理を証明した。[[ハッセの原理|局所大域定理]]――[[代数体|数体]]上の有限次元中心可除代数がいたるところ局所的に分解するならば大域的にも分解する(したがって自明である)――を証明し、これから次の ''Hauptsatz''(「主定理」)を演繹した:''[[代数的数|代数]][[可換体|体]] F 上の任意の有限次元[[中心的単純多元環|中心]][[可除代数]]は[[アーベル拡大|巡回円分拡大]]上分解する''。これらの定理によって与えられた数体上のすべての有限次元中心可除代数を分類することができる。それに続くネーターの論文は、より一般的な定理の特別な場合として、可除代数 ''D'' のすべての極大部分体は[[分解体]]であることを示した{{Sfn | Noether | 1933}}。この論文は{{仮リンク|スコレム・ネーターの定理|en|Skolem–Noether theorem}}も含んでいる。この定理は、体 ''k'' の拡大の ''k'' 上の有限次元中心単純代数への任意の2つの埋め込みは共役であるというものである。{{仮リンク|ブラウアー・ネーターの定理|en|Brauer–Noether theorem}}{{Sfn |Brauer | Noether | 1927}}は体上の中心可除代数の分解体の特徴づけを与える。 |

|||

==Assessment, recognition, and memorials== |

|||

{{further|List of things named after Emmy Noether#Other}} |

|||

[[File:Emmy-noether-campus siegen.jpg|thumb|250px|right|The Emmy Noether Campus at the [[University of Siegen]] is home to its mathematics and physics departments.]] |

|||

Noether's work continues to be relevant for the development of theoretical physics and mathematics and she is consistently ranked as one of the greatest mathematicians of the twentieth century. In his obituary, fellow algebraist [[Bartel Leendert van der Waerden|BL van der Waerden]] says that her mathematical originality was "absolute beyond comparison",{{Sfn |Dick|1981|p=100}} and Hermann Weyl said that Noether "changed the face of [[abstract algebra|algebra]] by her work".<ref name="weyl_128">{{Harvnb|Dick|1981|p= 128}}</ref> During her lifetime and even until today, Noether has been characterized as the greatest woman mathematician in recorded history by mathematicians{{Sfn |Osen|1974|p= 152}}{{Sfn | Alexandrov | 1981 | p = 100}}{{Sfn |James|2002|p= 321}} such as [[Pavel Alexandrov]],{{Sfn | Dick | 1981 | p= 154}} [[Hermann Weyl]],{{Sfn | Dick| 1981| p= 152}} and [[Jean Dieudonné]].<ref name = "g_noether_p167">{{Harvnb | Noether | 1987 | p = 167}}.</ref> |

|||

In a letter to ''[[The New York Times]]'', [[Albert Einstein]] wrote:<ref name="einstein">{{Citation | last = Einstein | first = Albert | title = Professor Einstein Writes in Appreciation of a Fellow-Mathematician | date = 1 May 1935 | url = http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70D1EFC3D58167A93C6A9178ED85F418385F9 | publication-date = 5 May 1935 | newspaper = [[New York Times]] | accessdate = 13 April 2008}}. Also [http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Obits2/Noether_Emmy_Einstein.html online] at the [[MacTutor History of Mathematics archive]].</ref> |

|||

{{Quote |In the judgment of the most competent living mathematicians, Fräulein Noether was the most significant creative mathematical [[genius]] thus far produced since the higher education of women began. In the realm of algebra, in which the most gifted mathematicians have been busy for centuries, she discovered methods which have proved of enormous importance in the development of the present-day younger generation of mathematicians.}} |

|||

On 2 January 1935, a few months before her death, mathematician [[Norbert Wiener]] wrote that {{Sfn | Kimberling | 1981|p= 35}} |

|||

{{quote |Miss Noether is... the greatest woman mathematician who has ever lived; and the greatest woman scientist of any sort now living, and a scholar at least on the plane of [[Marie Curie|Madame Curie]].}} |

|||

At an exhibition at the 1964 [[World's fair|World's Fair]] devoted to [[Mathematica: A World of Numbers... and Beyond|Modern Mathematicians]], Noether was the only woman represented among the notable mathematicians of the modern world.<ref>{{Citation | last = Duchin | first = Moon | url = http://www.math.lsa.umich.edu/~mduchin/UCD/111/readings/genius.pdf | title = The Sexual Politics of Genius | format = PDF |date=December 2004 | publisher = University of Chicago | accessdate = 23 March 2011}} (Noether's birthday).</ref> |

|||

Noether has been honored in several memorials, |

|||

* The [[Association for Women in Mathematics]] holds a [[Noether Lecture]] to honor women in mathematics every year; in its 2005 pamphlet for the event, the Association characterizes Noether as "one of the great mathematicians of her time, someone who worked and struggled for what she loved and believed in. Her life and work remain a tremendous inspiration".<ref>{{Citation | chapter-url = http://www.awm-math.org/noetherbrochure/Introduction.html | chapter = Introduction | title = Profiles of Women in Mathematics | series = The Emmy Noether Lectures | publisher = [[Association for Women in Mathematics]] | year = 2005 | accessdate = 13 April 2008}}.</ref> |

|||

* Consistent with her dedication to her students, the [[University of Siegen]] houses its mathematics and physics departments in buildings on ''the Emmy Noether Campus''.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://www.uni-siegen.de/uni/campus/wegweiser/emmy.html | title = Emmy-Noether-Campus | publisher = Universität Siegen | place = [[Germany|DE]] | accessdate = 13 April 2008}}.</ref> |

|||

* The German Research Foundation ([[Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft]]) operates the ''Emmy Noether Programme'', a scholarship providing funding to promising young post-doctorate scholars in their further research and teaching activities.<ref>[http://www.dfg.de/en/research_funding/programmes/coordinated_programmes/collaborative_research_centres/modules/emmy_noether/ "Emmy Noether Programme: In Brief"]. ''Research Funding''. [[Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft]]. n.d. Retrieved on 5 September 2008.</ref> |

|||

* A street in her hometown, Erlangen, has been named after Emmy Noether and her father, Max Noether. |

|||

* The successor to the secondary school she attended in Erlangen has been renamed as ''the Emmy Noether School''.<ref name="g_noether_p167" /> |

|||

* A series of high school workshops and competitions are held in her honor in May of each year since 2001, originally hosted by a subsequent woman mathematics [[Privatdozent]] of the [[University of Göttingen]].<ref>Emmy Noether High School Mathematics Days. http://www.math.ttu.edu/~enoether/</ref> |

|||

*[[Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics]] annually awards Emmy Noether Visiting Fellowships <ref>Emmy Noether Visiting Fellowships http://www.perimeterinstitute.ca/emmy-noether-visiting-fellowships</ref> to outstanding female theoretical physicists. Perimeter Institute is also home to the Emmy Noether Council,<ref>Emmy Noether Council http://www.perimeterinstitute.ca/support-pi/emmy-noether-council</ref> a group of volunteers made up of international community, corporate and philanthropic leaders work together to increase the number of women in physics and mathematical physics at Perimeter Institute. |

|||

* The Emmy Noether Mathematics Institute in Algebra, Geometry and Function Theory in the Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, [[Bar-Ilan University]], Ramat Gan, Israel was jointly founded in 1992 by the university, the [[German government]] and the [[Minerva Foundation]] with the aim to stimulate research in the above fields and to encourage collaborations with Germany. Its main topics are [[Algebraic Geometry]], [[Group theory]] and [[Complex Function Theory]]. Its activities includes local research projects, conferences, short-term visitors, post-doc fellowships, and the Emmy Noether lectures (an annual series of distinguished lectures). ENI is a member of ERCOM: "European Research Centers of Mathematics".<ref>The Emmy Noether Mathematics Institute. http://u.cs.biu.ac.il/~eni/</ref> |

|||

In fiction, Emmy Nutter, the physics professor in "The God Patent" by [[Ransom Stephens]], is based on Emmy Noether.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://ransomstephens.com/the-god-patent.htm | title = The God Patent | first = Ransom | last = Stephens}}.</ref> |

|||

Farther from home, |

|||

* The crater [[Nöther (crater)|Nöther]] on the [[far side of the Moon]] is named after her. |

|||

* The [[7001 Noether]] asteroid also is named for Emmy Noether.{{Sfn |Schmadel|2003| p= 570}}<ref>Blue, Jennifer. [http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/ Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature]. [[United States Geological Survey|USGS]]. 25 July 2007. Retrieved on 13 April 2008.</ref> |

|||

* [[Google]] put a memorial [[Google doodle|doodle]] on Google's homepage in many countries on 23 March 2015 to celebrate Emmy Noether's 133rd birthday.<ref>[https://www.google.com/doodles/emmy-noethers-133rd-birthday Google Doodles: Emmy Noether's 133rd Birthday] 2015-03-23.</ref> |

|||

==List of doctoral students== |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" id="Noether_doctoral_students" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Date !! Student name !! Dissertation title and English translation !! University !! Publication |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1911.12.16 || Falckenberg, Hans || Verzweigungen von Lösungen nichtlinearer Differentialgleichungen |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| Ramifications of Solutions of Nonlinear Differential Equations<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Erlangen || Leipzig 1912 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1916.03.04 || Seidelmann, Fritz || Die Gesamtheit der kubischen und biquadratischen Gleichungen mit Affekt bei beliebigem Rationalitätsbereich |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| Complete Set of Cubic and Biquadratic Equations with Affect in an Arbitrary Rationality Domain<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Erlangen || Erlangen 1916 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1925.02.25 || [[Grete Hermann|Hermann, Grete]] || Die Frage der endlich vielen Schritte in der Theorie der Polynomideale unter Benutzung nachgelassener Sätze von Kurt Hentzelt |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| The Question of the Finite Number of Steps in the Theory of Ideals of Polynomials using Theorems of the Late Kurt Hentzelt<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1926 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1926.07.14 || Grell, Heinrich || Beziehungen zwischen den Idealen verschiedener Ringe |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| Relationships between the Ideals of Various Rings<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1927 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1927 ||Doräte, Wilhelm || Über einem verallgemeinerten Gruppenbegriff |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| On a Generalized Conceptions of Groups<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1927 |

|||

|- |

|||

| died before defense || Hölzer, Rudolf || Zur Theorie der primären Ringe |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| On the Theory of Primary Rings<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1927 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1929.06.12 || Weber, Werner || Idealtheoretische Deutung der Darstellbarkeit beliebiger natürlicher Zahlen durch quadratische Formen |

|||

{| |

|||

| Ideal-theoretic Interpretation of the Representability of Arbitrary Natural Numbers by Quadratic Forms<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1930 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1929.06.26 || Levitski, Jakob || Über vollständig reduzible Ringe und Unterringe |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| On Completely Reducible Rings and Subrings<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1931 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1930.06.18 || [[Max Deuring|Deuring, Max]] || Zur arithmetischen Theorie der algebraischen Funktionen |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| On the Arithmetic Theory of Algebraic Functions<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1932 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1931.07.29 || [[Hans Fitting|Fitting, Hans]] || Zur Theorie der Automorphismenringe Abelscher Gruppen und ihr Analogon bei nichtkommutativen Gruppen |

|||

{| |

|||

| On the Theory of Automorphism-Rings of Abelian Groups and Their Analogs in Noncommutative Groups<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1933 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1933.07.27 || [[Ernst Witt|Witt, Ernst]] || Riemann-Rochscher Satz und Zeta-Funktion im Hyperkomplexen |

|||

{| |

|||

| The Riemann-Roch Theorem and Zeta Function in Hypercomplex Numbers<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Berlin 1934 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1933.12.06 || [[Zeng Jiongzhi|Tsen, Chiungtze]] || Algebren über Funktionenkörpern |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| Algebras over Function Fields<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || Göttingen 1934 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1934 || Schilling, Otto || Über gewisse Beziehungen zwischen der Arithmetik hyperkomplexer Zahlsysteme und algebraischer Zahlkörper |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

| On Certain Relationships between the Arithmetic of Hypercomplex Number Systems and Algebraic Number Fields<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Marburg || Braunschweig 1935 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1935 || Stauffer, Ruth || The construction of a normal basis in a separable extension field |

|||

| Bryn Mawr || Baltimore 1936 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1935 || Vorbeck, Werner || Nichtgaloissche Zerfällungskörper einfacher Systeme |

|||

{| |

|||

| Non-Galois [[Splitting field|Splitting Fields]] of Simple Systems<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1936 || Wichmann, Wolfgang || Anwendungen der p-adischen Theorie im Nichtkommutativen |

|||

{| |

|||

| Applications of the ''p''-adic Theory in Noncommutative Algebras<sup>§</sup> |

|||

|} |

|||

| Göttingen || ''Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik'' (1936) '''44''', 203–24. |

|||

|} |

|||

==Eponymous mathematical topics== |

|||

{{main|{{仮リンク|エミー・ネーターに因んで名づけられた物事の一覧|en|List of things named after Emmy Noether}}}} |

|||

{{col-begin}} |

|||

{{col-3}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|ネーター的|en|Noetherian (disambiguation)}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|ネーター群|en|Noetherian group}} |

|||

* [[ネーター環]] |

|||

* [[ネーター加群]] |

|||

* [[ネーター空間]] |

|||

{{col-3}} |

|||

* [[ネーター帰納法]] |

|||

* [[ネータースキーム]] |

|||

* {{仮リンク|ネーターの正規化定理|en|Noether normalization lemma}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|ネーターの問題|en|Noether problem}} |

|||

{{col-3}} |

|||

* [[ネーターの定理]] |

|||

* {{仮リンク|ネーターの第二定理|en|Noether's second theorem}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|ラスカー・ネーターの定理|en|Lasker–Noether theorem}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|スコレム・ネーターの定理|en|Skolem–Noether theorem}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|アルバート・ブラウアー・ハッセ・ネーターの定理|en|Albert–Brauer–Hasse–Noether theorem}} |

|||

{{col-end}} |

|||

==脚注== |

|||

{{脚注ヘルプ}} |

{{脚注ヘルプ}} |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist |colwidth=30em}} |

||

==参考文献== |

|||

== 外部リンク == |

|||

===エミー・ネーターの選集(ドイツ語)=== |

|||

{{Commonscat|Emmy Noether}} |

|||

{{main |{{仮リンク|エミー・ネーターの出版物一覧|en|List of publications by Emmy Noether}}}} |

|||

* {{citation| last= Noether| first= Emmy | title = Über die Bildung des Formensystems der ternären biquadratischen Form | trans_title = On Complete Systems of Invariants for Ternary Biquadratic Forms | journal =Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik | volume= 134 | year = 1908 | pages = 23–90 and two tables | url = http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/no_cache/dms/load/img/?IDDOC=261200 | publisher = Uni Göttingen | place = [[Germany|DE]] | language = German | doi=10.1515/crll.1908.134.23}}. |

|||

* {{citation| last= Noether|first= Emmy | author-mask = 3 |title= Rationale Funktionenkörper | trans_title = Rational Function Fields | journal = J. Ber. D. DMV|volume=22|year= 1913|pages= 316–19 | url = http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/no_cache/dms/load/img/?IDDOC=244058 | publisher = Uni Göttingen | place = DE | language = German}}. |

|||