「プラスチック汚染」の版間の差分

Dušan Kreheľ (bot) (会話 | 投稿記録) More used with only one reference definition: 2 new references and 3 new reference calls. |

en: Plastic pollution (20:54, 26 October 2023 UTC) を翻訳したものを統合し、加筆整理 タグ: サイズの大幅な増減 ビジュアルエディター 曖昧さ回避ページへのリンク |

||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

{{ |

{{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} |

||

{{multiple image|perrow = 2|total_width=350 |

|||

'''プラスチック汚染'''(プラスチックおせん、[[英語|英]]: plastic pollution)とは、ごみ問題の一つ<ref name="ahegao">{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1589019/plastic-pollution |title=Plastic pollution |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |access-date=2023-07-03}}</ref><ref name="ikigao">{{cite web |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/06/plastic-planet-waste-pollution-trash-crisis |title=We Depend on Plastic. Now We're Drowning in It. |access-date=2023-07-03}}</ref><ref name="jstage">{{Cite web|和書|url=https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/seitai/66/1/66_51/_pdf/-char/ja|title=海洋生態系におけるプラスチックの動態と生物への影響|publisher=日本生態学会誌 |accessdate=2023-07-03}}</ref>。 |

|||

| header = プラスチック汚染の例 |

|||

| image1 = Lepidochelys olivacea Landaa.JPG |

|||

| image2 = Beach in Sharm el-Naga03.jpg |

|||

| image3 = Pollution plastique 2.jpg |

|||

| image4 = Piles of plastic waste in Thilafushi, 2012 (2).jpg |

|||

| image5 = Plastic bottle adjacent to hiking trail.jpg|thumb|Plastic Bottle Canada Dry.jpg |

|||

| footer = プラスチック汚染は海、ビーチ、川、陸地に悪影響を及ぼす(左上から時計回りに): • モルディブでゴーストネットに絡まったオリーブリドリーカメ • エジプト、サファガ近くのシャルム・エル・ナガビーチのプラスチック汚染 • モルディブの政府承認を受けた「ゴミの島」ティラフシのプラスチック廃棄物の山 • アメリカの都市近くのハイキングトレイルにあるプラスチックボトル • カメルーン、ドゥアラのプラスチックで完全に詰まったウォウリ川の支流}} |

|||

'''プラスチック汚染'''は、適切に処理されなかったプラスチックゴミが河川や海へ流出し、海洋や自然環境に影響を与えるものであり、<ref>{{Cite web |title=Plastic pollution {{!}} Definition, Sources, Effects, Solutions, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/plastic-pollution |website=www.britannica.com |date=2023-11-02 |access-date=2023-11-07 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=We Depend on Plastic. Now We’re Drowning in It. |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/plastic-planet-waste-pollution-trash-crisis |website=Magazine |date=2018-05-16 |access-date=2023-11-07 |language=en}}</ref><ref>https://www.kokusen.go.jp/wko/pdf/wko-202102_07.pdf 国民生活センター</ref> 人間、野生生物、およびその生息地に悪影響を及ぼす地球環境にプラスチック製品やその破片(例:プラスチックボトル、袋、[[マイクロビーズ]]など)が蓄積することをいう。<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1589019/plastic-pollution |title=Plastic pollution |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |access-date=1 August 2013}}</ref><ref name=":15">{{cite web |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/06/plastic-planet-waste-pollution-trash-crisis |title=We Depend on Plastic. Now We're Drowning in It. |author=Laura Parker |date=June 2018 |website=[[NationalGeographic.com]] |access-date=25 June 2018}}</ref> <ref name="plastics in marine environment">{{Cite book |last1=Hammer|first1=J|last2=Kraak|first2=MH|last3=Parsons|first3=JR|title=Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology|chapter=Plastics in the Marine Environment: The Dark Side of a Modern Gift|date=2012|volume=220|pages=1–44|doi=10.1007/978-1-4614-3414-6_1|pmid=22610295|isbn=978-1461434139|s2cid=5842747|chapter-url=https://semanticscholar.org/paper/43553427495a7cc4d727f75bebc6b67b4e710393}}</ref> プラスチックは安価で耐久性があり、さまざまな用途に適しているため、あらゆる商品の製造業者はプラスチック材料を汎用する。<ref>Hester, Ronald E.; Harrison, R. M. (editors) (2011). [https://books.google.com/books?id=TCfYfIDymd8C&pg=PA84 Marine Pollution and Human Health]. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 84–85. {{ISBN|184973240X}}</ref> ほとんどのプラスチックの化学構造は自然の分解プロセスに対して抵抗性があるため、自然環境下では極めて分解が遅い。<ref name="Plastic Pollution">{{cite web |title=When The Mermaids Cry: The Great Plastic Tide |last1=Le Guern |first1=Claire |date=March 2018 |website=Coastal Care |url=https://coastalcare.org/2020/01/plastic-pollution-when-the-mermaids-cry-the-great-plastic-tide-by-claire-le-guern/ |access-date=2023-11-5}}</ref> これらの2つの理由により、大量のプラスチックが未処理の廃棄物として環境に侵入し、[[生態系]]内に残存し、[[食物連鎖]]を通じて広がり、地球規模で汚染を引き起こしている。<ref name="Worm">{{cite journal|last1=Worm|first1=Boris|last2=Lotze|first2=Heike K.|last3=Jubinville|first3=Isabelle|last4=Wilcox|first4=Chris|last5=Jambeck|first5=Jenna|date=17 October 2017|title=Plastic as a Persistent Marine Pollutant|url=https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060700|journal=Annual Review of Environment and Resources|volume=42|issue=1|pages=1–26|language=en|doi=10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060700|issn=1543-5938}}</ref><ref name="Ong" /> |

|||

プラスチック汚染は地球上の陸地、水路、海洋のいずれにも影響を及ぼす。陸地沿岸の人類居住地から年間1,100万から880万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が海洋に入る。<ref name="Science2015">{{Cite journal|last1=Jambeck|first1=Jenna R.|last2=Geyer|first2=Roland|last3=Wilcox|first3=Chris|last4=Siegler|first4=Theodore R.|last5=Perryman|first5=Miriam|last6=Andrady|first6=Anthony|last7=Narayan|first7=Ramani|last8=Law|first8=Kara Lavender|date=2015-02-13|title=Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean|url=https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1260352|journal=Science|volume=347|issue=6223|pages=768–771|language=EN|doi=10.1126/science.1260352|pmid=25678662|bibcode=2015Sci...347..768J|s2cid=206562155}}</ref> 2013年末時点で、世界の海洋には8600万トンのプラスチックの[[海洋ゴミ]]があると推定され、1950年から2013年までに世界で生産されたプラスチックの約1.4%が海洋に入り、そこに蓄積しているとの見積もりもある。<ref name="kci.go.kr">Jang, Y. C., Lee, J., Hong, S., Choi, H. W., Shim, W. J., & Hong, S. Y. 2015. "Estimating the global inflow and stock of plastic marine debris using material flow analysis: a preliminary approach". ''Journal of the Korean Society for Marine Environment and Energy'', 18(4), 263–273.[https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiOrteView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002050087]</ref> |

|||

== 概要 == |

|||

プラスチック汚染は、適切に処理されなかったプラスチックゴミが河川や海へ流出し、海洋や自然環境に影響を与えるものである。<ref name="名前なし-20231105145346">[https://www.kokusen.go.jp/wko/pdf/wko-202102_07.pdf プラスチックゴミの何が問題なの?] 国民生活センター、2023年7月3日閲覧。</ref> |

|||

[[国際連合|国連]]広報センターなどによれば、プラスチックゴミの9割がリサイクルされていなく、'''2050年までに海洋において棲息している全魚類よりも海洋ごみプラスチックの重量のほうが多くなる可能性がある'''との示唆がある。<ref>{{Cite web |title=やめよう、プラスチック汚染 |url=https://www.unic.or.jp/activities/economic_social_development/sustainable_development/beat_plastic_pollution/ |website=国連広報センター |access-date=2023-11-07 |language=ja}}</ref><ref name="Sutter">{{cite web|last=Sutter|first=John D.|date=12 December 2016|title=How to stop the sixth mass extinction|url=http://www.cnn.com/2016/12/12/world/sutter-vanishing-help/|access-date=18 September 2017|work=CNN}}</ref> 生物、特に海洋生物、はプラスチック物体に絡まるなどの機械的な影響、プラスチック廃棄物の摂取により引き起こされる問題、およびプラスチック内の化学物質による体内の生理機能への影響により害を受ける。さらに、分解されたプラスチック廃棄物は、直接摂取(飲料水など)、間接的な摂取(植物や動物を食べることにより)やさまざまな[[ホルモン]]メカニズムの妨害を通じて、人類にも影響を及ぼす。<ref name="Ziani">{{cite journal |last1=Ziani |first1=K |last2=Ioniță-Mîndrican |first2=CB |last3=Mititelu |first3=M |last4=Neacșu |first4=SM |last5=Negrei |first5=C |last6=Moroșan |first6=E |last7=Drăgănescu |first7=D |last8=Preda |first8=OT |title=Microplastics: A Real Global Threat for Environment and Food Safety: A State of the Art Review. |journal=Nutrients |date=25 January 2023 |volume=15 |issue=3 |page=617 |doi=10.3390/nu15030617 |pmid=36771324 |pmc=9920460 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

また、国連広報センターは、プラスチックゴミの9割がリサイクルされていなく、その数がすでに銀河系の星の数、2050年には魚の数を超えると予測されていると指摘した<ref name="名前なし_2-20231105145346">[https://www.unic.or.jp/activities/economic_social_development/sustainable_development/beat_plastic_pollution/ やめよう、プラスチック汚染]国際連合広報センター、2023年7月3日閲覧</ref>。 |

|||

2019年現在、年間で368百万トンのプラスチックが生産されており、その51%は中国などアジアで生産されている。<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.plasticseurope.org/application/files/8016/1125/2189/AF_Plastics_the_facts-WEB-2020-ING_FINAL.pdf |title=Plastics – the Facts 2020 |access-date=6 October 2021 |archive-date=1 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210901235830/https://www.plasticseurope.org/application/files/8016/1125/2189/AF_Plastics_the_facts-WEB-2020-ING_FINAL.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> 1950年から2018年までに、世界中で推定63億トンのプラスチックが生産され、その約9%が[[リサイクル]]され、別の12%が焼却されたと推定されている。<ref name="economist.com">{{cite news |title=The known unknowns of plastic pollution |url=https://www.economist.com/news/international/21737498-so-far-it-seems-less-bad-other-kinds-pollution-about-which-less-fuss-made |access-date=17 June 2018 |newspaper=The Economist |date=3 March 2018}}</ref> この大量のプラスチック廃棄物は環境に侵入し、生態系全体で問題を引き起こす。90%の[[海鳥]]の体にプラスチックゴミが含まれているとする研究がある。<ref name=":16">{{cite web |url=https://globalnomadic.com/turning-rubbish-into-money-environmental-innovation-leads-the-way/ |title=Turning rubbish into money – environmental innovation leads the way |first=Global |last=Nomadic |date=29 February 2016 |access-date=2023-11-5}}</ref><ref name="plasticizer">{{cite journal|last1=Mathieu-Denoncourt|first1=Justine|last2=Wallace|first2=Sarah J.|last3=de Solla|first3=Shane R.|last4=Langlois|first4=Valerie S.|date=November 2014|title=Plasticizer endocrine disruption: Highlighting developmental and reproductive effects in mammals and non-mammalian aquatic species|journal=General and Comparative Endocrinology|volume=219|pages=74–88|doi=10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.11.003|pmid=25448254|doi-access=free}}</ref> 一部の地域では、プラスチックの消費削減、ゴミの清掃、およびプラスチックのリサイクルの推進を通じて、野外のプラスチック汚染の目立つ存在を減らすための取り組みが行われている。<ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.02.014|title = A call for Canada to move toward zero plastic waste by reducing and recycling single-use plastics| journal=Resources, Conservation and Recycling| volume=133| pages=99–100|year = 2018|last1 = Walker|first1 = Tony R.| last2=Xanthos| first2=Dirk|s2cid = 117378637}}</ref><ref name=":17">{{cite web |url=https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/picking-litter-pointless-exercise-or-powerful-tool-battle-beat-plastic |title=Picking up litter: Pointless exercise or powerful tool in the battle to beat plastic pollution? |author=<!--Not stated-->|date=18 May 2018 |website=unenvironment.org |access-date=19 July 2019}}</ref> |

|||

そして遠い海岸に漂着し、観光業や漁業に打撃を与えるなどの被害も報告されている<ref name="名前なし-20231105145346"/>。 |

|||

'''2020年現在までに生産されたプラスチックの総質量は、陸地と海洋のすべての動植物の生物量を上回っている。'''<ref>{{cite news |last=Laville |first=Sandra |date=December 9, 2020 |title=Human-made materials now outweigh Earth's entire biomass – study |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/09/human-made-materials-now-outweigh-earths-entire-biomass-study |access-date=December 9, 2020}}</ref> 2019年5月、[[開発途上国|発展途上国]]への[[先進国]]からのプラスチック廃棄物の輸出/輸入を規制し防ぐことを意図して[[バーゼル条約]]の修正が採択された。<ref name="nationalgeographic.com">National Geographic, 30 Oct. 2020, [https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/us-plastic-pollution "U.S. Generates More Plastic Trash than Any Other Nation, Report Finds: The Plastic Pollution Crisis Has Been Widely Blamed on a Handful of Asian Countries, But New Research Shows Just How Much the U.S. Contributes"]</ref><ref name=":20">UN Environment Programme, 12 May 2019 [https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/governments-agree-landmark-decisions-protect-people-and-planet "Governments Agree Landmark Decisions to Protect People and Planet from Hazardous Chemicals and Waste, Including Plastic Waste"]</ref><ref name=":21">The Guardian, 10 May 2019, [https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/10/nearly-all-the-worlds-countries-sign-plastic-waste-deal-except-us "Nearly All Countries Agree to Stem Flow of Plastic Waste into Poor Nations: US Reportedly Opposed Deal, which Follows Concerns that Villages in Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia Had ‘Turned into Dumpsites’"]</ref><ref name=":22">Phys.org, 10 May 2019 [https://phys.org/news/2019-05-nations-export-plastic.html "180 Nations Agree UN Deal to Regulate Export of Plastic Waste"]</ref> 2022年3月2日、ナイロビで175カ国が、2024年の年末までにプラスチック汚染を終わらせる目標で法的拘束力のある合意を作成することを誓約した。<ref name="unep.org">{{cite web |title=Historic day in the campaign to beat plastic pollution: Nations commit to develop a legally binding agreement |url=https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/historic-day-campaign-beat-plastic-pollution-nations-commit-develop |website=UN Environment Programme (UNEP) |date=2 March 2022 |access-date=11 March 2022}}</ref> |

|||

近年になってプラスチック汚染問題は国際社会でクローズアップされ、2015年6月に開催された[[G7]]・[[エルマウサミット]]において海洋ゴミ問題が世界的問題であることを確認し、「海洋ごみ問題に対処するためのG7行動計画を策定した<ref name="名前なし-20231105145346"/>。 |

|||

[[COVID-19パンデミック]]中、保護具と包装材の需要の増加によりプラスチック廃棄物の量は増加し、<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Shams |first1=Mehnaz |last2=Alam |first2=Iftaykhairul |last3=Mahbub |first3=Md Shahriar |date=October 2021 |title=Plastic pollution during COVID-19: Plastic waste directives and its long-term impact on the environment |journal=Environmental Advances |volume=5 |pages=100119 |doi=10.1016/j.envadv.2021.100119 |issn=2666-7657 |pmc=8464355 |pmid=34604829}}</ref> 特に医療廃棄物や使い捨てマスク由来の廃棄プラスチックの海洋への流入が増えた。<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ana |first=Silva |year=2021 |title=Increased Plastic Pollution Due to Covid-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Recommendations. |journal=Chemical Engineering Journal |volume=405 |page=126683 |doi=10.1016/j.cej.2020.126683 |pmc=7430241 |pmid=32834764}}</ref><ref name="Euronews Bubble Barrier">{{cite web |last1=Limb |first1=Lottie |title=The Great Bubble Barrier: How bubbles are keeping plastic out of the sea |url=https://www.euronews.com/green/2021/09/22/great-bubble-barrier-how-bubbles-are-keeping-plastic-out-of-the-sea |website=euronews.com |date=22 September 2021 |publisher=Euronews.green |access-date=November 26, 2021}}</ref> いくつかのニュースレポートは、プラスチック業界が一般社会のパンデミックに対する怖れや使い捨てマスク・包装の需要増加に乗じて、使い捨てプラスチックの生産を増やすことを目論んだと指摘した。<ref name=":24">{{Cite web |date=2020-03-13 |title=Plastics industry adapts to business during COVID-19 |url=https://www.plasticsnews.com/news/plastics-industry-adapts-business-during-covid-19 |access-date=2021-12-18 |website=Plastics News |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":25">{{Cite web |title=Plastic in the time of a pandemic: protector or polluter? |url=https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/plastic-pollution-waste-pandemic-covid19-coronavirus-recycling-sustainability/ |access-date=2021-12-18 |website=World Economic Forum |date=6 May 2020 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":26">{{Cite web |last=Monella |first=Lillo Montalto |date=2020-05-12 |title=Will plastic pollution get worse after the COVID-19 pandemic? |url=https://www.euronews.com/2020/05/12/will-plastic-pollution-get-worse-after-the-covid-19-pandemic |access-date=2021-12-18 |website=euronews |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":27">{{Cite web |last=Westervelt |first=Amy |date=2020-01-14 |title=Big Oil Bets Big on Plastic |url=https://drillednews.com/big-oil-bets-big-on-plastic/ |access-date=2021-12-18 |website=Drilled News |language=en-US |archive-date=18 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211218161024/https://drillednews.com/big-oil-bets-big-on-plastic/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

== 生態系への影響 == |

|||

紫外線や海流、波によって[[マイクロプラスチック]]となり、有害物質が付着しやすくなって、鳥や魚が食べ、その魚や鳥を食物連鎖を通じて人やその他の生物が食べることによって生体を傷つける<ref name="名前なし_2-20231105145346"/><ref>[https://www.cuc.ac.jp/om_miraitimes/column/u0h4tu00000013vf.html 海が汚染され、海の生物も人も危ない! マイクロプラスチック汚染問題とは] 千葉商科大学、2023年3月22日公開、2023年7月3日閲覧</ref>などの被害が報告され、実例として2018年に[[タイ王国|タイ]]の南部でくじらの胃から80袋以上の袋が見つかったり、プラスチック片を誤飲して胃がいっぱいになって餓死するウミドリやプラスチック製漁網が魚や鳥に絡まった<ref>[https://www.greenpeace.org/japan/explore/plastic#problem ゼロから分かるプラスチック問題と海洋汚染]グリーンピース公式サイト、2023年7月3日閲覧。</ref>などの例が挙げられる。 |

|||

== 汚染源 == |

|||

また、[[国連環境計画]]は、プラスチックゴミが毎年数十万の海の生物の死を引き起こすと発表した<ref>[https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411982/Assessing_the_impact_of_exposure_to_microplastics_in_fish_report.pdf Assessing the impact of exposure to microplastics in fish] 2023年7月3日閲覧</ref> |

|||

{{See also|Timeline of plastic development}}[[File:Pathway-of-plastic-to-ocean.png|thumb|400px|世界の海洋にプラスチックが流入する経路]]過去100年間にどれだけのプラスチック廃棄物が生成されたかについて一つの見積りによれば、1950年代以来、約10億トンのプラスチック廃棄物が廃棄されてきたとされている。<ref>{{cite book |title=The world without us |vauthors=Weisman A |date=2007 |publisher=Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press |isbn=978-1443400084 |location=New York}}</ref> 他の見積りは、累積的な人間のプラスチック生産量が83億トンで、そのうち63億トンが廃棄物であり、そのうち9%しかリサイクルされていないと推定した。<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL |date=July 2017 |title=Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made |journal=Science Advances |volume=3 |issue=7 |pages=e1700782 |bibcode=2017SciA....3E0782G |doi=10.1126/sciadv.1700782 |pmc=5517107 |pmid=28776036}}</ref><ref name=":11">{{Cite web |last=Environment |first=U.N. |date=2021-10-21 |title=Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics |url=http://www.unep.org/resources/report/drowning-plastics-marine-litter-and-plastic-waste-vital-graphics |access-date=2022-03-21 |website=UNEP – UN Environment Programme |language=en}}</ref> この廃棄物のうち、81%が重合体樹脂、13%が重合体繊維、32%が添加物から成ると推定されている。2018年には3億4300万トン以上のプラスチック廃棄物が発生し、そのうち90%が消費者使用後廃棄物([[産業廃棄物]]、農業廃棄物、商業廃棄物、市町村の家庭ごみ)で、残りはプラスチック材料の生産とプラスチック製品の製造過程での廃棄物である(例:色、硬さ、または加工特性が適していないために不適格とされる材料など)。<ref name=":11" /> |

|||

'''消費者使用後プラスチック廃棄物の大部分は包装材である。'''米国では、プラスチック包装が[[都市廃棄物]](各自治体でごみ処理される家庭ごみ)の5%を占めると推定されている。包装材製品にはプラスチックボトル、ポット、タブ、トレイ、レジ袋、ゴミ袋、バブルラップ(”プチプチ”)、発泡プラスチック(例:発泡スチロール(EPS))などがあり、農業(例:散水パイプ、温室カバー、フェンス、ペレット、マルチ)、建設(例:パイプ、塗料、床材、屋根材、断熱材、シーリング材)、交通(例:摩耗したタイヤ、道路表面、道路標識)、電子機器と電気機器([[電気電子機器廃棄物|e-waste]])、医薬品および医療などの多くのセクターで発生する。<ref name=":11" /> |

|||

== 脚注 == |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

いくつかの研究は国内および国際的なレベルで環境へのプラスチック流出を定量化しようとしているが、研究によりその見積もり量は大きく異なり、すべての発生源と発生量を決定する困難さを示している。一つの研究は、2010 年には沿岸国 192 か国で 2 億 7,500 万トン のプラスチック廃棄物が発生し、480 万トンから 1,270 万トンが海洋に流入したと計算した。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Jambeck|first=Jenna R.|last2=Geyer|first2=Roland|last3=Wilcox|first3=Chris|last4=Siegler|first4=Theodore R.|last5=Perryman|first5=Miriam|last6=Andrady|first6=Anthony|last7=Narayan|first7=Ramani|last8=Law|first8=Kara Lavender|date=2015-02-13|title=Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean|url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1260352|journal=Science|volume=347|issue=6223|pages=768–771|language=en|doi=10.1126/science.1260352|issn=0036-8075}}</ref>''' '''Borrelle et al. 2020によれば、2016年には約1,900万から2,300万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が水生生態系に入った。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Borrelle|first=Stephanie B.|last2=Ringma|first2=Jeremy|last3=Law|first3=Kara Lavender|last4=Monnahan|first4=Cole C.|last5=Lebreton|first5=Laurent|last6=McGivern|first6=Alexis|last7=Murphy|first7=Erin|last8=Jambeck|first8=Jenna|last9=Leonard|first9=George H.|date=2020-09-18|title=Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution|url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aba3656|journal=Science|volume=369|issue=6510|pages=1515–1518|language=en|doi=10.1126/science.aba3656|issn=0036-8075}}</ref> 一方、Pew Charitable TrustsとSYSTEMIQ(2020)によれば、同じ年に約900万から1,400万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が海に流入した。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lau|first=Winnie W. Y.|last2=Shiran|first2=Yonathan|last3=Bailey|first3=Richard M.|last4=Cook|first4=Ed|last5=Stuchtey|first5=Martin R.|last6=Koskella|first6=Julia|last7=Velis|first7=Costas A.|last8=Godfrey|first8=Linda|last9=Boucher|first9=Julien|date=2020-09-18|title=Evaluating scenarios toward zero plastic pollution|url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aba9475|journal=Science|volume=369|issue=6510|pages=1455–1461|language=en|doi=10.1126/science.aba9475|issn=0036-8075}}</ref> |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物の生成を削減するための世界的な取り組みにもかかわらず、環境への損失は増加すると予測される。有効な介入措置がない限り、2040年までに年間2,300万から3,700万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が海に流入し、'''2060年までには年間1億5500万から2億6500万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が環境に排出される可能性がある'''。需要に推進されるままにプラスチック製品を増産し続け、[[廃棄物処理|廃棄物管理]]の改善が不十分なままであれば、これらの増加が環境上の大災害につながることはほぼ確実である。<ref name=":11" /> |

|||

== プラスチック廃棄物の主な発生国と海洋流入国 == |

|||

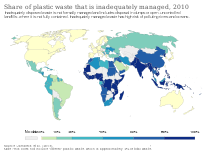

[[File:Share of plastic waste that is inadequately managed, OWID.svg|thumb|管理不適切なプラスチック廃棄物の割合]] |

|||

[[File:Per capita mismanaged plastic waste, OWID.svg|thumb|1人当たりの管理不適切なプラスチック廃棄物(1日あたりのキログラム単位)]]経済先進国から発展途上国、特に北米や欧州からアジア諸国へのプラスチック廃棄物の輸出は「海洋のごみの主要な元凶」として特定されている。 何故ならしばしばそのような'''廃棄プラスチック輸入国は十分な廃棄物処理能力を持たない'''からである。したがって国際連合は特定の基準を満たさない限り、'''[[バーゼル条約|廃棄プラスチックの取引に対する禁止]]'''を課したが、<ref>{{Citation|title=Plastic pollution|date=2023-10-27|url=https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plastic_pollution&oldid=1182119805|language=en|access-date=2023-11-01}}</ref> 2022年現在その禁止条約は十分遵守されているとは言えない状況にある(「政策>廃棄プラスチック国際条約の不遵守」の項を参照)。 |

|||

=== プラスチック廃棄物発生国 === |

|||

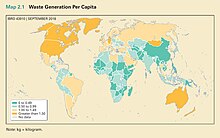

'''米国はプラスチック廃棄物の発生において突出して世界一'''で、年間4200万トンのプラスチック廃棄物を生成している。<ref>The Guardian, 1 Dec. 2021 [https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/01/deluge-of-plastic-waste-us-is-worlds-biggest-plastic-polluter?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other "‘Deluge of Plastic Waste’: US Is World’s Biggest Plastic Polluter; At 42m Metric Tons of Plastic Waste a Year, The US Generates More Waste than All EU Countries Combined"]</ref><ref>2021 Consensus Study Report of the Committee of Experts of the United States National Academies of Engineering, Sciences and Medicine [https://www.nap.edu/catalog/26132/reckoning-with-the-us-role-in-global-ocean-plastic-waste "Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste"]</ref> 米国の1人当たりのプラスチック廃棄物の生成量は、他のどの国よりも多く平均して1人当たり年間130キログラムである。EU-28([[欧州連合]]+英国、年間1人当たり59キログラム)も多いが、高所得国でも日本(年間1人当たり38キログラム)などのようにずっと少ないところもある。<ref>Statista, Ian Tiseo, 14 Apr. 2021 [https://www.statista.com/statistics/1228043/plastic-waste-generation-per-capita-in-select-countries/ "Per capita plastic waste generation in select countries worldwide in 2016(in kilograms a year)"]</ref><ref>Science, 30 Oct. 2020 [https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abd0288 "The United States’ Contribution of Plastic Waste to Land and Ocean"]</ref> '''日本'''は1人当たり量は少なくても年間891万トンとなっており(2018年)、<ref>https://www.env.go.jp/content/900515691.pdf 廃プラスチックのリサイクル等に関する 国内及び国外の状況について、環境省 2019年 |

|||

</ref> 統計や年度にもよるが世界第2位から5位と'''プラスチック廃棄物発生国としては世界最上位ランクにある'''。 |

|||

=== 海洋へのプラスチック廃棄物の流入国 === |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物の海洋への流入は主にアジアで起こっている。 <ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20150223140548/http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB20530567965804683707904580457713291864670 Harald Franzen (30 November 2017). ''The Wall Street Journal''. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. リンク切れ</ref> 以下の表は2015年に発表された[[サイエンス|Science]]のJambeckらによる研究による、海洋流入プラスチック廃棄物の多い国々である。すべての欧州連合諸国を合わせるとこの表では 18 位にランクされる。<ref name="Science2015" /><ref name="earthday.org">{{cite web |url=https://www.earthday.org/2018/04/06/top-20-countries-ranked-by-mass-of-mismanaged-plastic-waste/ |title=Top 20 Countries Ranked by Mass of Mismanaged Plastic Waste |date=4 June 2018 |website=[[Earth Day]].org |access-date=2023-11-5}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-putting-the-most-plastic-waste-into-the-oceans.html |title=Countries Putting The Most Plastic Waste Into The Oceans |date=18 September 2019 |author=Kushboo Sheth |website=worldatlas.com |access-date=2023-11-5}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="text-align:right" |

|||

|+プラスチック廃棄物の多い国々上位20か国 |

|||

!Position |

|||

!Country |

|||

!Plastic pollution <br />(in 1000 [[tonnes]] per year) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | 中国 |

|||

| 8820 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | インドネシア |

|||

| 3220 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 3 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | フィリピン |

|||

| 1880 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 4 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | ベトナム |

|||

| 1830 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 5 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | スリランカ |

|||

| 1590 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 6 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | タイ |

|||

| 1030 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 7 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | エジプト |

|||

| 970 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 8 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | マレーシア |

|||

| 940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 9 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | ナイジェリア |

|||

| 850 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 10 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | バングラデシュ |

|||

| 790 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 11 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | 南アフリカ |

|||

| 630 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 12 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | [[India|インド]] |

|||

| 600 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 13 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | アルジェリア |

|||

| 520 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 14 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | トルコ |

|||

| 490 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 15 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | パキスタン |

|||

| 480 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 16 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | ブラジル |

|||

| 470 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 17 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | ミャンマー |

|||

| 460 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 18 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | モロッコ |

|||

| 310 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 19 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | 北朝鮮 |

|||

| 300 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 20 |

|||

| style="text-align:left; " | 米国 |

|||

| 280 |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

2019年の研究では、適切に管理されていないプラスチック廃棄物の年間発生量を百万トン(Mt)単位で以下のように計算した。<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Lebreton, Laurent|last2=Andrady, Anthony|date=2019|title=Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal|journal=Palgrave Communications|volume=5|issue=1|publisher=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]]|doi=10.1057/s41599-018-0212-7|issn=2055-1045|id=Lebreton2019|quote=the Asian continent was in 2015 the leading generating region of plastic waste with 82 Mt, followed by Europe (31 Mt) and Northern America (29 Mt). Latin America (including the Caribbean) and Africa each produced 19 Mt of plastic waste while Oceania generated about 0.9 Mt.|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

* 52 Mt – アジア |

|||

* 17 Mt – アフリカ |

|||

* 7.9 Mt – 南米と中米 |

|||

* 3.3 Mt – 欧州 |

|||

* 0.3 Mt – 北米 |

|||

* 0.1 Mt – オセアニア (オーストラリア、ニュージーランドなど) |

|||

2020年に行われた研究では、2016年における米国による管理不適切なプラスチックへの寄与を見直し、米国で廃棄されたプラスチックがインドネシアとインドに続いて海洋汚染で3番目に多い可能性があると推定した。<ref>{{Cite web |title=U.S. generates more plastic trash than any other nation, report finds |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/us-plastic-pollution |website=Environment |date=2020-10-30 |access-date=2023-11-06 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

2021年の[[:en:_The_Ocean_Cleanup|The Ocean Cleanup]]の研究では、河川が海洋に年間800万から270万トンのプラスチックを流入させているとし、改めてこれらの川の属する国々を新たにランク付けした。上位10カ国は最も多いものから、フィリピン、インド、マレーシア、中国、インドネシア、ミャンマー、ブラジル、ベトナム、バングラデシュ、タイとなっていた。<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Meijer|first1=Lourens J. J.|last2=Van Emmerik|first2=Tim|last3=Van Der Ent|first3=Ruud|last4=Schmidt|first4=Christian|last5=Lebreton|first5=Laurent|year=2021|title=More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean|journal=Science Advances|volume=7|issue=18|bibcode=2021SciA....7.5803M|doi=10.1126/sciadv.aaz5803|pmc=8087412|pmid=33931460}}</ref> 中国は2016年以降プラスチック廃棄物の輸入を停止したことで流入量を減少させることに成功した形になっている。 |

|||

2022年の研究では、OECD加盟国(北米、チリ、コロンビア、欧州、イスラエル、日本、韓国)が海洋プラスチック汚染の5%を寄与し、世界の残りが95%を汚染していると推定した。<ref>{{cite news |author1=Hannah Ritchie |author1-link=Hannah Ritchie |title=Ocean plastics: How much do rich countries contribute by shipping their waste overseas? |url=https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-waste-trade |access-date=12 October 2022 |work=Our World in Data |date=11 October 2022 |language=en |quote=Most of the plastic that enters the oceans from land comes from rivers in Asia. More than 80% of it [...] a few percent – possibly up to 5% – of the world’s ocean plastics could come from rich countries exporting their waste overseas}}</ref> |

|||

2022年に[[米国科学アカデミー|米国国立科学アカデミー]]は、世界全体で海洋へのプラスチック流入が年間800万トンであると推定した。<ref>{{cite book |author1=((National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine)) |title=Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste |date=2022 |publisher=The National Academies Press |location=Washington |isbn=978-0-309-45885-6 |page=1 |url=https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26132/reckoning-with-the-us-role-in-global-ocean-plastic-waste |access-date=20 June 2022 |language=en |chapter=Summary |quote=An estimated 8 million metric tons (MMT) of plastic waste enter the world’s ocean each year}}</ref> |

|||

== プラスチック汚染とそのサイズ == |

|||

[[File:Beach cleanup.jpg|thumb|ガーナの海岸の清掃]] |

|||

プラスチック汚染に貢献している主要なプラスチックはそのサイズにより、[[マイクロプラスチック]]、マクロプラスチック、メガプラスチックの三つに分類される。メガプラスチックとマイクロプラスチックは、北半球で最も高い密度で蓄積しており、都市部や水辺周辺に集中して存在している。[[海流]]によって運ばれるプラスチック廃棄物のため、一部の島の沖にも見られる。メガプラスチックとマクロプラスチックは、船から流出したり[[埋立地]]に廃棄されたりした包装材、履物、その他の家庭用品として見つかる。漁業関連プラスチック廃棄物は、海流により運ばれた[[離島|遠隔の島]]の周辺で見つかる可能性が高い。<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Walker|first1=T.R.|last2=Reid|first2=K.|last3=Arnould|first3=J.P.Y.|last4=Croxall|first4=J.P.|year=1997|title=Marine debris surveys at Bird Island, South Georgia 1990–1995|journal=Marine Pollution Bulletin|volume=34|issue=1|pages=61–65|bibcode=1997MarPB..34...61W|doi=10.1016/S0025-326X(96)00053-7}}</ref><ref name="Barnes">{{cite journal|last1=Barnes|first1=D. K. A.|last2=Galgani|first2=F.|last3=Thompson|first3=R. C.|last4=Barlaz|first4=M.|date=14 June 2009|title=Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments|journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences|volume=364|issue=1526|pages=1985–1998|doi=10.1098/rstb.2008.0205|pmc=2873009|pmid=19528051}}</ref> [[File:Plastic bottle stuck on edge of river.jpg|thumb|川のほとりに引っかかったプラスチックボトル]] |

|||

=== マイクロプラスチック === |

|||

[[File:Microplastics in the surface ocean, OWID.svg|thumb|表面の海洋における1950年から2000年までのマクロプラスチックとその先の予測、百万トン単位]] |

|||

{{Main|Microplastics}} |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物の破片は劣化や衝突によってさらに小さな片に分解された[[マイクロプラスチック]]となる。<ref name="Barnes" /> またプラスチック業界でプラスチック製品の製造に広く使用されている小さなプラスチックペレット (5 mm 未満)を一般的に[[:en:_Nurdle_(bead)|ナードル]]といい、これもサイズ上マイクロプラスチックである。ナードルは新しいプラスチック製品を作るために試用されるが、その際その小さなサイズのために製造工程中に環境に漏洩しやすく、これもしばしば河川を通じて海洋に流出する。<ref name="plastics in marine environment" /> 海洋にあるプラスチックの10%が[[:en:_Nurdle_(bead)|ナードル]]であると推定されており、プラスチック袋や食品容器とともに、最も一般的なプラスチック汚染のタイプの一つである。<ref name="Knight2">Knight 2012, p. 11.</ref><ref name="Knight4">Knight 2012, p. 13.</ref> また、クリーニング(人工繊維衣類の洗濯下水に漏洩するプラスチック繊維など)や化粧品製品から発生するマイクロプラスチックはスクラバーとも呼ばれる。マイクロプラスチックはその非常に小さなサイズのため、[[濾過摂食]]する生物が摂取しうる。<ref name="plastics in marine environment" /> マイクロプラスチック中の[[ビスフェノールA]]、[[ポリスチレン]]、[[DDT]]、[[ポリ塩化ビフェニル|PCB]]などの[[残留性有機汚染物質|持続性]]かつ[[生物濃縮]]性毒物はこれら生物に蓄積し、[[食物連鎖]]を通じて魚を摂食する人間に有害な影響を引き起こしうる。<ref name="Knight3">Knight 2012, p. 12.</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nurdlehunt.org.uk/whats-the-problem/small-plastics.html |title=Small, Smaller, Microscopic! |access-date=30 November 2017 |language=en-gb |archive-date=1 December 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201043531/https://www.nurdlehunt.org.uk/whats-the-problem/small-plastics.html |website=The Great Nurdle Hunt |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

英国のプリマス大学のリチャード・トンプソンによる2004年の研究によれば、欧州、米国、オーストラリア、アフリカ、南極などのビーチや水域において大量のマイクロプラスチックが発見された。<ref name="Plastic Pollution" /> 彼らは家庭用および産業用のプラスチック製ペレットが、人間の髪の毛よりも小さい直径のプラスチック片に分解され浮遊していることを発見した。 海洋表面平方キロメートルあたり30万個のプラスチック片があり、海底平方キロメートルあたり10万個の[[:en:_Plastic_pellet_pollution|プラスチック粒子]]があるかもしれないと予測している。<ref name="Plastic Pollution" /> [http://pelletwatch.jp/ インターナショナル・ペレット・ウォッチ]は、17カ国の30のビーチからポリエチレン製のペレットのサンプルを収集し、有機微汚染物質の分析を行った。米国、ベトナム、南アフリカのビーチで見つかったペレットには、農薬由来の化合物が含まれており、これらの地域で農薬の使用量が多いことを示唆した。<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Otaga|first1=Y.|year=2009|title=International Pellet Watch: Global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in coastal waters. 1. Initial phase data on PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs|url=http://psasir.upm.edu.my/id/eprint/40332/1/International%20Pellet%20Watch%20global%20monitoring%20of%20persistent%20organic%20pollutants%20%28POPs%29%20in%20coastal%20waters.%201.%20Initial%20phase%20data%20on%20PCBs%2C%20DDTs%2C%20and%20HCHs.pdf|journal=Marine Pollution Bulletin|volume=58|issue=10|pages=1437–1446|bibcode=2009MarPB..58.1437O|doi=10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.06.014|pmid=19635625}}</ref> 2020年、科学者たちは、オーストラリア沖の約300キロ離れた深さ約3キロの6つの地域を調査した結果、[[海底]]に現在存在するマイクロプラスチックの量について、おそらく初の科学的推定を作成した。それによれば高度によって変動するマイクロプラスチックのカウントは、海洋表面のマイクロプラスチック量と海底の勾配の角度に比例していた。立方センチメートルあたりの平均マイクロプラスチック質量を計算すると、'''地球の海底には約1400万トンのマイクロプラスチックが含まれている'''と推定され、これは以前の研究からのデータを基にした推定量の約1-2倍である。<ref>{{cite news |last1=May |first1=Tiffany |title=Hidden Beneath the Ocean's Surface, Nearly 16 Million Tons of Microplastic |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/07/world/australia/microplastics-ocean-floor.html |access-date=30 November 2020 |work=The New York Times |date=7 October 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=14 million tonnes of microplastics on sea floor: Australian study |url=https://phys.org/news/2020-10-million-tonnes-microplastics-sea-floor.html |access-date=9 November 2020 |work=phys.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Barrett|first1=Justine|last2=Chase|first2=Zanna|last3=Zhang|first3=Jing|last4=Holl|first4=Mark M. Banaszak|last5=Willis|first5=Kathryn|last6=Williams|first6=Alan|last7=Hardesty|first7=Britta D.|last8=Wilcox|first8=Chris|date=2020|title=Microplastic Pollution in Deep-Sea Sediments From the Great Australian Bight|journal=Frontiers in Marine Science|volume=7|language=en|doi=10.3389/fmars.2020.576170|issn=2296-7745|author-link2=Zanna Chase|doi-access=free|s2cid=222125532}} [[ファイル:CC-BY_icon.svg|50x50ピクセル]] Available under [[creativecommons:by/4.0/|CC BY 4.0]].</ref> |

|||

=== マクロプラスチック === |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| total_width = 320 |

|||

| image1 = Plastikmüll Im Meer (150229847).jpeg |

|||

| image2 = Macroplastics in the surface ocean, OWID.svg |

|||

| caption1 = レジ袋はマクロデブリの一例 |

|||

| caption2 = 1950 ~ 2000 年の海洋表層におけるマクロプラスチックとそれ以降の予測 (百万トン単位)。 |

|||

}} |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物は、サイズが20 mmより大きい場合、マクロプラスチックとして分類され、[[レジ袋]]などが含まれる。<ref name="plastics in marine environment" /> マクロプラスチックは海洋水域によく見られ、現地の生物に深刻な影響を与える。[[漁網]]も主要なマクロプラスチック汚染源である。漁網は放棄された後でも、海洋生物や他のプラスチック廃棄物を捕らえ続け、最終的に総重量最大6トンに増加し水から引き上げるのが非常に困難になる。<ref name="plastics in marine environment" /> |

|||

== 悪影響 == |

|||

[[File:Decomposition rates of marine debris items, OWID.svg|thumb|典型的な海洋廃棄物の平均推定分解時間。プラスチック廃棄物は青で表示]] |

|||

{{Main|Polymer degradation}}一般にプラスチックの劣化分解は極めて遅く、その廃棄物は環境中に長期間残留する。<ref name="Barnes" /> 最近の研究では、海洋中のプラスチックは従来考えられていたよりも速く断片化することが示されており、太陽光、雨などの環境条件にさらされて有害物質([[ビスフェノールA]]など)が放出される。<ref name="ScienceDaily">{{cite web |last1=Chemical Society |first1=American |title=Plastics in Oceans Decompose, Release Hazardous Chemicals, Surprising New Study Says |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/08/090819234651.htm |website=Science Daily |access-date=15 March 2015}}</ref> いくつかのプラスチック製品の分解速度が推定されており、発泡スチロールカップは50年、プラスチック製の飲料ホルダーは400年、使い捨ておむつは450年、釣り糸は600年と推定されている。<ref name="Plastic Pollution" /> |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物の分布は風や海洋の流れ、海岸線の地理、都市地域、貿易路などの要因によって非常に変動する。また特定の地域の人口にも大きく影響される。例えばカリブ海などの閉じた地域により多く見られる傾向があり、ある生物種が本来の生息地でない遠隔地の岸に侵入分布するキャリアとして働くことで、その移動先の地域で[[生物多様性]]の変動と[[:en:_Biological_dispersal|生物種の分散]]が増加する原因となりうる。プラスチック廃棄物はまた、[[残留性有機汚染物質]]や[[重金属]]などの化学的汚染物のキャリアとしても働きうる。これらの汚染物質は、[[赤潮]]に関連付けられる藻類の拡散増加とも関連している。<ref name="Barnes" /> |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物はまた、[[残留性有機汚染物質]]や[[重金属]]などの化学的汚染物のキャリアとしても働きうる。これらの汚染物質は、[[赤潮]]に関連付けられる藻類の拡散増加とも関連している。<ref name="Barnes" /> |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| width = 200 |

|||

| footer = ガーナのビーチで集められたプラスチック廃棄物の袋を運ぶ人々 |

|||

| image1 = Beach plastic waste 3.jpg |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| image2 = Beach plastic waste 7.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

| caption2 = |

|||

}} |

|||

2022年1月、科学者のグループが「新しい実体」(プラスチック汚染を含む汚染)のための'''[[プラネタリー・バウンダリー|地球の境界を定義し、既に超えられている]]'''ことが判明した。共著者である[[:en:_Stockholm_Resilience_Centre|ストックホルム・レジリエンス・センター]]のパトリシア・ヴィラルビア=ゴメスによれば、1950年以来、化学物質の生産量は50倍に増加し、2050年までにさらに3倍に増加する見通しとなっている。世界には少なくとも35万の人工化学物質が存在し、プラスチックだけでも1万を超え、”[[:en:_Planetary_health|地球の健康]]”に悪影響を及ぼすとし、化学物質の生産を制限し、[[サーキュラーエコノミー|再利用とリサイクル]]が可能な製品に移行することを呼びかけている。<ref>{{cite web |title=Safe planetary boundary for pollutants, including plastics, exceeded, say researchers |url=https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2022-01-18-safe-planetary-boundary-for-pollutants-including-plastics-exceeded-say-researchers.html |website=Stockholm Resilience Centre |date=18 January 2022 |access-date=28 January 2022}}</ref> |

|||

=== 気候変動への悪影響 === |

|||

2019年に公表された「プラスチックと気候」の新しい報告書によれば、2019年にプラスチックの生産と焼却により、大気中に850百万トンの[[二酸化炭素]](CO2)に相当する[[温室効果ガス]]が放出し、その傾向が続くとこれらからの年間排出量は2030年までに134億トンに増加する。2050年までにプラスチックは地球の残りの[[:en:_Carbon_budget|炭素予算]]の14%に相当する560億トンの温室効果ガスを放出し、<ref>{{cite web |title=Sweeping New Report on Global Environmental Impact of Plastics Reveals Severe Damage to Climate |url=https://www.ciel.org/news/plasticandclimate/ |website=Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) |access-date=16 May 2019}}</ref> 2100年までには炭素予算の半分以上に相当する2600億トンを放出すると見積もられた。これらは生産、輸送、焼却からの排出で、その他[[メタン]]の放出や[[植物プランクトン]]への影響もある。<ref>{{cite book |title=Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet |date=May 2019 |url=https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-Executive-Summary-2019.pdf |access-date=28 May 2019}}</ref> |

|||

=== 陸地への悪影響 === |

|||

陸地でのプラスチック汚染は、陸地に生息する植物や動物、そして陸地に基づく人間にとって脅威をもたらす。<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/02/180205125728.htm |title=An underestimated threat: Land-based pollution with microplastics |author=<!--Not stated--> |date=5 February 2018 |website=sciencedaily.com |access-date=19 July 2019}}</ref> 陸地上のプラスチックの濃度の推定値は、海洋のそれの4倍から23倍の範囲で濃縮されている。<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/plastic-planet-how-tiny-plastic-particles-are-polluting-our-soil |title=Plastic planet: How tiny plastic particles are polluting our soil |author=<!--Not stated--> |date=3 April 2019 |website=unenvironment.org |access-date=19 July 2019}}</ref> 管理不適切なプラスチック廃棄物は、東アジアと太平洋地域の60%から北米の1%まで幅広く、毎年海に流れ込む管理不適切なプラスチック廃棄物の割合は、その年の総不適切廃棄物の1/3から1/2の範囲である。<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution#mismanaged-plastic-waste |title=Mismanaged plastic waste |author=<!--Not stated--> |date=2010 |journal=Our World in Data |access-date=19 July 2019 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.statista.com/chart/12211/the-countries-polluting-the-oceans-the-most/ |title=The Countries Polluting The Oceans The Most |last=McCarthy |first=Niall |website=statista.com |access-date=19 July 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

2021年には、[[国際連合食糧農業機関]](FAO)による報告書が発表され、プラスチックが農業で汎用されていることが指摘された。'''土壌には海洋よりも多くのプラスチックが存在する'''。土壌環境中のプラスチックは生態系と人間の健康に害を及ぼし、食品の安全に脅威をもたらす。<ref>{{cite news |last1=Carrington |first1=Damian |title='Disastrous' plastic use in farming threatens food safety – UN |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/07/disastrous-plastic-use-in-farming-threatens-food-safety-un |access-date=8 December 2021 |agency=The Guardian |date=7 December 2021}}</ref> 特に[[塩素化]]プラスチックは周囲の土壌に有害な化学物質を放出し、それが[[地下水汚染|地下水]]や他の周囲の水源、そして世界の生態系に浸透し、<ref>{{Cite book |title=Interactive Environmental Educatiaon Book VIII |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8_d2Wkgq_rYC&pg=PA86 |publisher=Pitambar Publishing |isbn=978-81-209-1373-8 |language=en}}</ref> 水を飲む生物種に深刻な害を及ぼす。2022年の研究はスイスを覆う雪にナノプラスチックが含まれており、スイス全体で約3000トンに達することを見出した。<ref>[https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/nanoplastics-snow/128298/ "Nanoplastics in snow: The extensive impact of plastic pollution".] ''Open Access Government''. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.</ref> |

|||

==== 洪水被害の増加 ==== |

|||

[[File:Community service carried out on sanitation day.jpg|thumb|ニジェリアのイロリンでボランティアの衛生デー中に溝を掃除しているボランティアたち。]] |

|||

プラスチックごみは[[雨水管|雨水排水路]]を詰まらせることで洪水被害を増加させ、特に都市部では問題となる。<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=Development solutions: Building a better ocean|url=https://www.eib.org/en/essays/plastic-pollution|access-date=2020-08-19|website=European Investment Bank|language=en}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Honingh |first1=Dorien |last2=van Emmerik |first2=Tim |last3=Uijttewaal |first3=Wim |last4=Kardhana |first4=Hadi |last5=Hoes |first5=Olivier |last6=van de Giesen |first6=Nick |date=2020 |title=Urban River Water Level Increase Through Plastic Waste Accumulation at a Rack Structure |journal=Frontiers in Earth Science |volume=8 |doi=10.3389/feart.2020.00028 |issn=2296-6463|doi-access=free }}</ref> バンコクでは既に過度に放流されている下水システムがプラスチックゴミによる詰まりのため、洪水のリスクが大幅に増加している。<ref name=":6">{{Cite news|last=hermesauto|date=2016-09-06|title=Plastic bags clogging Bangkok's sewers complicate efforts to fight floods|url=https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/plastic-bags-clogging-bangkoks-sewers-complicate-efforts-to-fight-floods|access-date=2020-11-17|website=The Straits Times|language=en}}</ref> このような状況では衛生施設のインフラが十分であっても、下水管理の悪化により'''衛生環境の悪化'''をもたらしうる。 |

|||

==== 水道水のプラスチック汚染 ==== |

|||

2017年の研究によれば'''世界中の飲料水サンプルの83%にプラスチックの汚染物質'''が含まれていた。<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=https://orbmedia.org/stories/Invisibles_plastics|title=Invisibles|website=orbmedia.org|access-date=15 September 2017|archive-date=6 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906172409/https://orbmedia.org/stories/Invisibles_plastics|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://orbmedia.org/stories/Invisibles_final_report|title=Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Global Drinking Water|website=orbmedia.org|access-date=19 September 2017}}</ref> これは飲料水のプラスチック汚染に関する初の研究で、<ref name=":2">{{Cite news|url=https://phys.org/news/2017-09-plastic.html|title=Your tap water may contain plastic, researchers warn (Update)|access-date=15 September 2017}}</ref> 米国の水道水の汚染率が94%で最も高く、レバノンとインドがこれに続いており、英国、ドイツ、フランスなどの欧州諸国は汚染率が低いものの、それでも72%であった。<ref name=":1" /> 人々は年間約3,000から4,000個のマイクロプラスチック粒子を水道水だけから摂取していると見積もられ、この分析では2.5マイクロン以上のサイズの粒子さえ見つかった。<ref name=":2" /> この汚染が人間の健康にどの程度の影響を与えているかは不明だが、研究に関与した科学者は人間の健康に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があるとしている。<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/sep/06/plastic-fibres-found-tap-water-around-world-study-reveals|title=Plastic fibres found in tap water around the world, study reveals |first=Damian |last=Carrington |date=5 September 2017|work=The Guardian|access-date=15 September 2017|language=en-GB|issn=0261-3077}}</ref> マイクロプラスチックの水道水汚染はまだ研究が不足しており、汚染物質が人間、大気、水、土壌の間でどのように移動するかも研究課題である。<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=http://time.com/4928759/plastic-fiber-tap-water-study/|title=Plastic Fibers Are Found in '83% of the World's Tap Water'|last=Lui|first=Kevin|magazine=Time|access-date=15 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

==== 陸上生態系のプラスチック汚染 ==== |

|||

陸地の生態系において 適切な処理や廃棄物の不適切な処理により、プラスチックごみが陸地の生態系に直接または間接的に入り込むことがある。<ref name=":7">Li, P., Wang, X., Su, M., Zou, X., Duan, L., & Zhang, H. (2020). Characteristics of plastic pollution in the environment: A Review. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 107(4), 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-020-02820-1</ref> プラスチック材料の不適切な取り扱いと廃棄により、マイクロプラスチック汚染が大幅に増加している。<ref name=":8">Mbachu, O., Jenkins, G., Kaparaju, P., & Pratt, C. (2021). The rise of artificial soil carbon inputs: Reviewing microplastic pollution effects in the soil environment. Science of the Total Environment, 780, 146569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146569</ref> 特に[[マイクロプラスチック]]の形でのプラスチック汚染は土壌に広く見られる。排水処理プラントには'''[[マイクロプラスチック]]を取り除く処理過程がない'''ため、マイクロプラスチックが含まれている排水を浄化処理した水が土壌に開放されると、そのマイクロプラスチックはそのまま土壌に移動する。<ref name=":10" /> 例えばいくつかの研究は、フリースや他のポリエステル製品を洗濯機で洗浄する際に放出される[[合成繊維]]を見つけた。<ref name=":12">Yang, J., Li, L., Li, R., Xu, L., Shen, Y., Li, S., Tu, C., Wu, L., Christie, P., & Luo, Y. (2021). Microplastics in an agricultural soil following repeated application of three types of sewage sludge: A field study. Environmental Pollution, 289, 117943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117943</ref> '''衣類の合成繊維もプラスチック製品の一種'''であり、排水を通じて土地に移動し土壌環境を汚染する。<ref name=":9" /> |

|||

表面に開放されたマイクロプラスチックは地下に移動し、<ref name=":9">Chae, Y., & An, Y.-J. (2018). Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A Review. Environmental Pollution, 240, 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.008</ref> やがて植物や動物に入り込む。<ref name=":10">Wei, F., Xu, C., Chen, C., Wang, Y., Lan, Y., Long, L., Xu, M., Wu, J., Shen, F., Zhang, Y., Xiao, Y., & Yang, G. (2022). Distribution of microplastics in the sludge of wastewater treatment plants in Chengdu, China. Chemosphere, 287, 132357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132357</ref> マイクロプラスチックは、土壌の生物物理的特性を変え、植物の成長に重要な土壌生態系に影響を与える。これは土壌中の生物活動、植物の生長を支えている微生物などの[[生物多様性]]、および植物の苗の発芽を減少させ、葉の数、幹の直径、および葉緑素含有量に影響する。<ref name=":8" /> 植物の健康は環境と生態系にとって基礎であり、結果としてプラスチックはこれらの生態系に生活するすべての生物にとって有害な影響をもたらす。<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

土壌生物多様性は、農業産業における作物の成長に重要である。[[:en:_Plasticulture|プラスチックマルチング]]や[[都市廃棄物]]の適用などの農業活動は、土壌中のマイクロプラスチック汚染に寄与している。人間が改変した土壌は作物の生産性を向上させるために一般的に使用されていても、その影響は有益よりも有害であり、<ref name=":8" /> 結果として土壌中のマイクロプラスチックは、食品の安全性や人間の健康にもリスクをもたらす。 |

|||

プラスチックはまた、環境に有毒物質を放出し、生物に対して物理的、化学的な害、生物的な損傷を引き起こす。プラスチックの摂取は、動物の腸管の閉塞によって死亡させるだけでなく、[[食物連鎖]]を通じて人間にも影響を与える可能性がある。<ref name=":7" /> |

|||

=== 淡水生態系への悪影響 === |

|||

淡水のプラスチック汚染に関する研究は、海洋生態系に比べてあまり進んでおらず、2018年時点でそのトピックに関する発表論文のうちわずか13%となっている。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Blettler |first1=Martín C.M. |last2=Abrial |first2=Elie |last3=Khan |first3=Farhan R. |last4=Sivri |first4=Nuket |last5=Espinola |first5=Luis A. |date=2018 |title=Freshwater plastic pollution: Recognizing research biases and identifying knowledge gaps |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0043135418304597 |journal=Water Research |language=en |volume=143 |pages=416–424 |doi=10.1016/j.watres.2018.06.015|pmid=29986250 |bibcode=2018WatRe.143..416B |s2cid=51617474 }}</ref> |

|||

[https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/plastic-waste-mismanaged 管理不適切なプラスチック廃棄物(MMPW)]は淡水域、地下の帯水層、および移動する淡水に侵入しうる。一部の地域では、近代の法律によってある程度制限されるようになったが、川へ直接廃棄物を投棄する歴史的な悪習慣がいまだに残っている。<ref name=":04">{{Cite journal |last1=Azevedo-Santos |first1=Valter M. |last2=Brito |first2=Marcelo F. G. |last3=Manoel |first3=Pedro S. |last4=Perroca |first4=Júlia F. |last5=Rodrigues-Filho |first5=Jorge Luiz |last6=Paschoal |first6=Lucas R. P. |last7=Gonçalves |first7=Geslaine R. L. |last8=Wolf |first8=Milena R. |last9=Blettler |first9=Martín C. M. |last10=Andrade |first10=Marcelo C. |last11=Nobile |first11=André B. |date=2021 |title=Plastic pollution: A focus on freshwater biodiversity |journal=Ambio |language=en |volume=50 |issue=7 |pages=1313–1324 |doi=10.1007/s13280-020-01496-5 |issn=0044-7447 |pmc=8116388 |pmid=33543362}}</ref> '''河川は海洋生態系にプラスチックを輸送する主要ルートであり、海洋のプラスチック汚染の約80%を供給している。'''<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Winton |first1=Debbie J. |last2=Anderson |first2=Lucy G. |last3=Rocliffe |first3=Stephen |last4=Loiselle |first4=Steven |date=2020 |title=Macroplastic pollution in freshwater environments: Focusing public and policy action |journal=Science of the Total Environment |language=en |volume=704 |pages=135242 |doi=10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135242|pmid=31812404 |bibcode=2020ScTEn.704m5242W |s2cid=208955699 |doi-access=free }}</ref> 年間のMMPW量によってランク付けされたトップ10の川流域に関する研究によれば、最も高いのは[[東シナ海]]へ流入する[[長江]]だった。アジアの川が年間の海洋プラスチック廃棄物の約67%を供給しており、これは大陸全体にわたる高い沿岸人口と、比較的多量の季節的降雨が大きな原因と考えられている。<ref name="10.1021/acs.est.7b02368">{{Cite journal |last1=Schmidt |first1=Christian |last2=Krauth |first2=Tobias |last3=Wagner |first3=Stephan |date=2017-11-07 |title=Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea |url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.7b02368 |journal=Environmental Science & Technology |language=en |volume=51 |issue=21 |pages=12246–12253 |doi=10.1021/acs.est.7b02368 |pmid=29019247 |bibcode=2017EnST...5112246S |issn=0013-936X}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lebreton |first1=Laurent C. M. |last2=van der Zwet |first2=Joost |last3=Damsteeg |first3=Jan-Willem |last4=Slat |first4=Boyan |last5=Andrady |first5=Anthony |last6=Reisser |first6=Julia |date=2017 |title=River plastic emissions to the world's oceans |journal=Nature Communications |language=en |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=15611 |doi=10.1038/ncomms15611 |pmid=28589961 |pmc=5467230 |bibcode=2017NatCo...815611L |issn=2041-1723}}</ref> |

|||

===== 無脊椎動物 ===== |

|||

以前に発表された、206種類の生物種をカバーしているあらゆる実験結果の包括的分析によれば、大多数の論文で魚がプラスチックを摂取していることが示された。<ref name=":04" /> これは、魚が他の生物よりもプラスチックを摂食しているわけではなく、魚類より下位の食物連鎖生物である水生植物、両生類、無脊椎動物などのプラスチックの影響が適切に研究されていないことを浮き彫りにしている。 |

|||

プラスチックの影響を分析した実験では、藻類の一種であるChlorella sppと一般的な[[ウキクサ]]のLemna minorにおいて、顕著な結果が得られた。[[ポリプロピレン]](PP)と[[ポリ塩化ビニル]](PVC)の[[マイクロプラスチック]]の比較で、PVCは前者により強い毒性があり光合成能力に負の影響を与えた。これは、この濃度のPVCが関連する藻類[[クロロフィルa]]を60%減少させたことに起因すると考えられた。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wu |first1=Yanmei |last2=Guo |first2=Peiyong |last3=Zhang |first3=Xiaoyan |last4=Zhang |first4=Yuxuan |last5=Xie |first5=Shuting |last6=Deng |first6=Jun |date=2019 |title=Effect of microplastics exposure on the photosynthesis system of freshwater algae |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0304389419304674 |journal=Journal of Hazardous Materials |language=en |volume=374 |pages=219–227 |doi=10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.04.039|pmid=31005054 |s2cid=125204296 }}</ref> 一方、ポリエチレンのマイクロビーズ(化粧品の研磨剤由来物)が淡水藻類L. minorに及ぼす影響を分析したところ、光合成色素や生産性には影響がなかったが、根の成長と根細胞の生存率が低下した。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kalčíková |first1=Gabriela |last2=Žgajnar Gotvajn |first2=Andreja |last3=Kladnik |first3=Aleš |last4=Jemec |first4=Anita |date=2017 |title=Impact of polyethylene microbeads on the floating freshwater plant duckweed Lemna minor |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0269749117311247 |journal=Environmental Pollution |language=en |volume=230 |pages=1108–1115 |doi=10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.050|pmid=28783918 }}</ref> 総じてこれらの結果は懸念材料であり、植物と藻類は水中生態系内で栄養分とガスの循環に欠かせず、その密度のために水質組成に重要な変化をもたらす可能性がある。 |

|||

甲殻類もプラスチックの存在に対する反応が分析されている。淡水甲殻類、特に欧州のカニとザリガニは、湖の漁業で使用される[[ポリアミド]]の[[漁網]]に絡まれることが証明されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Spirkovski|first=Z.|last2=Ilik-Boeva|first2=D.|last3=Ritterbusch|first3=D.|last4=Peveling|first4=R.|last5=Pietrock|first5=M.|date=2019-03-01|title=Ghost net removal in ancient Lake Ohrid: A pilot study|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165783618302923|journal=Fisheries Research|volume=211|pages=46–50|doi=10.1016/j.fishres.2018.10.023|issn=0165-7836}}</ref> ポリスチレンの[[ナノ粒子]]にさらされた場合、Daphnia galeata(一般的な[[ミジンコ]])は48時間以内に生存率が減少し増殖活動に問題が生じた。5日後には妊娠したDaphniaの量は約50%減少し、影響なしに生き残った胚の割合は20%未満にまで減少した。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Cui |first1=Rongxue |last2=Kim |first2=Shin Woong |last3=An |first3=Youn-Joo |date=2017-09-21 |title=Polystyrene nanoplastics inhibit reproduction and induce abnormal embryonic development in the freshwater crustacean Daphnia galeata |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12299-2 |journal=Scientific Reports |volume=7 |issue=1 |page=12095 |doi=10.1038/s41598-017-12299-2 |pmid=28935955 |pmc=5608696 |bibcode=2017NatSR...712095C |issn=2045-2322}}</ref> 他の節足動物、特に昆虫の幼虫も、水中で完全に浸かった状態で過ごすことがあるため、類似したプラスチックの影響を受ける可能性が高いことから、昆虫類もプラスチックの影響を受ける可能性がある。 |

|||

===== 脊椎動物 ===== |

|||

[[File:Robin killed by trash in Prospect Park (60663).jpg|thumb|捨てられた釣り糸に絡まって死んだコマツグミ]] |

|||

両生類へのプラスチック曝露はほとんどが、より水生環境に依存している時期の若齢期の段階で研究されている。一般的な南米国の淡水カエル、Physalaemus cuvieriに関する研究では、プラスチックが変異原性や細胞毒性の形態学的変化を誘発する可能性があることが示唆された。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Araújo |first1=Amanda Pereira da Costa |last2=Malafaia |first2=Guilherme |date=2020 |title=Can short exposure to polyethylene microplastics change tadpoles' behavior? A study conducted with neotropical tadpole species belonging to order anura (Physalaemus cuvieri) |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122214 |journal=Journal of Hazardous Materials |volume=391 |pages=122214 |doi=10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122214 |pmid=32044637 |s2cid=211079532 |issn=0304-3894}}</ref> 特に両生類は環境の悪化の初期の[[指標生物|指標種]]としての役割を果たすことがあるため、プラスチック汚染に対する両生類の応答に関してさらなる研究が必要とされる。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Niemi |first1=Gerald J. |last2=McDonald |first2=Michael E. |date=2004-12-15 |title=Application of Ecological Indicators |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130132 |journal=Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics |volume=35 |issue=1 |pages=89–111 |doi=10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130132 |issn=1543-592X}}</ref> |

|||

淡水哺乳動物と鳥類は長らくプラスチック汚染との負の相互作用が知られており、しばしば絡まりや窒息/喉に詰まることがあります。これらのグループの消化管内での炎症が観察されているが、<ref name=":19" /> これらの生物におけるプラスチック汚染の毒理学的効果に関するデータはいまだ少ない。<ref name=":04" /> |

|||

魚類は淡水生物の中でプラスチック汚染に関して最も多く研究されており、野外で採取されたサンプルでも実験室でのモデル生物でもプラスチック摂取の証拠が多数得られている。<ref name=":04" /> 一般的な淡水モデル種である''Danio rerio''([[ゼブラフィッシュ]])におけるプラスチックの致死性を調べる研究がいくつか行われ、その消化管で粘液の増産と炎症反応が観察され、さらに腸内[[微生物叢|細菌叢]]内の微生物種分布が明らかに乱されたことが示された。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Jin |first1=Yuanxiang |last2=Xia |first2=Jizhou |last3=Pan |first3=Zihong |last4=Yang |first4=Jiajing |last5=Wang |first5=Wenchao |last6=Fu |first6=Zhengwei |date=2018 |title=Polystyrene microplastics induce microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in the gut of adult zebrafish |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.088 |journal=Environmental Pollution |volume=235 |pages=322–329 |doi=10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.088 |pmid=29304465 |issn=0269-7491}}</ref> この発見は重要である。何故なら過去数十年間の研究から、腸内[[微生物叢|細菌叢]]は宿主の栄養吸収と内分泌系に対し大きく影響することが確実であり、別の言い方をすれば'''適切な腸内[[微生物叢|細菌叢]]の維持は人間を含む宿主の健康に極めて重要である'''からである。<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rastelli |first1=Marialetizia |last2=Cani |first2=Patrice D |last3=Knauf |first3=Claude |date=2019-05-13 |title=The Gut Microbiome Influences Host Endocrine Functions |journal=Endocrine Reviews |volume=40 |issue=5 |pages=1271–1284 |doi=10.1210/er.2018-00280 |pmid=31081896 |s2cid=153306607 |issn=0163-769X|doi-access=free }}</ref> そのため、プラスチック汚染は人類を含む個々の生物の健康に対して現在考えられているよりもはるかに重大な悪影響を与える可能性があり、さらなる探索が急務である。またこれらの研究の多くの実験室内で実施されており、野生環境・個体群におけるプラスチックの存在量と毒性の測定もより多くの研究が必要である。 |

|||

=== 海洋と海洋生物への悪影響 === |

|||

[[File:Albatross at Midway Atoll Refuge (8080507529).jpg|thumb|right|2009年9月、太平洋のミッドウェイ環礁国立野生生物保護区で撮影された、死んだアホウドリの雛。胃内容物には、親から餌と間違われて与えられたプラスチックの海洋ゴミがそのままである。]][[漂流・漂着ごみ|海洋漂流・漂着ごみ]]は主に海洋に浮かんでいるか、または海洋に浮遊している人間のゴミで、その80%がプラスチックである。[[:en:_Marine_plastic_pollution|海洋プラスチック廃棄物汚染]]は、大きなボトルやバッグなどのオリジナルの大きさから、プラスチック材料の破砕によって形成される[[マイクロプラスチック]]まで、さまざまなサイズのものがある。<ref>{{Cite book|和書 |title=Weisman, Alan. The World Without Us. |year=2007 |publisher=St. Martin's Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0312347291.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Marine plastic pollution |url=https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/marine-plastic-pollution |website=www.iucn.org |access-date=2023-11-02 |language=en}}</ref> 海洋プラスチック廃棄物の分布は風や海洋の流れ、海岸線の地理、都市地域、沿岸地域人口、貿易路などの要因によって非常に変動し、[[太平洋ゴミベルト|ごみベルト]]・[[:en:_Garbage_patch|ごみパッチ]]と呼ばれる海洋ごみの集積体を特定の海域に形成する。推定では年間全世界のプラスチック生産の1.5-4%が海に流れ込んでおり、これは主に'''プラスチックの廃棄に対する無責任な態度と不適切な廃棄物管理方法ないしインフラ'''が原因である。 |

|||

2013年末現在、世界中の海洋に8600万トンのプラスチック海洋ゴミがあると推定されており、1950年から2013年までに世界のプラスチックの1.4%が海洋に入り蓄積されたと推測されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Jang|first=Yong Chang|last2=Lee|first2=Jongmyoung|last3=Hong|first3=Sunwook|last4=Choi|first4=Hyun Woo|last5=Shim|first5=Won Joon|last6=Hong|first6=Su Yeon|date=2015-11|title=Estimating the Global Inflow and Stock of Plastic Marine Debris Using Material Flow Analysis : a Preliminary Approach :a Preliminary Approach|url=https://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE06558843|journal=한국해양환경·에너지학회지|volume=18|issue=4|pages=263–273|language=ko|issn=2288-0089}}</ref>''' [[:en:_United_Nations_Ocean_Conference|2017年の国連の海洋会議]]では、2050年までに海洋がそこに棲息する魚類の全重量を上回るほどのプラスチックが流出しているかもしれないと推定されている。<ref>{{Cite web |title=UN Ocean Conference: Plastics Dumped In Oceans Could Outweigh Fish by 2050, Secretary-General Says |url=https://weather.com/science/environment/news/united-nations-ocean-conference-antonio-guterres-plastics |website=The Weather Channel |access-date=2023-11-02 |language=en-US}}</ref>''' 2021年の報告では年間約1900万から2300万トンのプラスチックが水生生態系に流出していると推定されている。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics |url=http://www.unep.org/resources/report/drowning-plastics-marine-litter-and-plastic-waste-vital-graphics |website=UNEP - UN Environment Programme |date=2021-10-21 |access-date=2023-11-02 |language=en |first=U. N. |last=Environment}}</ref> 2022年の時点では、プラスチックの消費は年間約3億トンと推定されており、そのうち約800万トンがマクロプラスチックとして海洋に流入している。<ref>{{Cite web |title=The average person eats thousands of plastic particles every year, study finds |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/you-eat-thousands-of-bits-of-plastic-every-year |website=Environment |date=2019-06-05 |access-date=2023-11-02 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":18">{{Cite journal|last=Bank|first=European Investment|date=2023-02-27|title=Microplastics and Micropollutants in Water: Contaminants of Emerging Concern|url=https://www.eib.org/en/publications/20230042-microplastics-and-micropollutants-in-water|language=EN}}</ref> マイクロプラスチックは約150万トンが海に流入し、このうち約98%は陸上、2%は海で生成している。<ref name=":18" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yuan|first=Zhihao|last2=Nag|first2=Rajat|last3=Cummins|first3=Enda|date=2022-06-01|title=Human health concerns regarding microplastics in the aquatic environment - From marine to food systems|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969722008221|journal=Science of The Total Environment|volume=823|pages=153730|doi=10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153730|issn=0048-9697}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=García Rellán|first=Adriana|last2=Vázquez Ares|first2=Diego|last3=Vázquez Brea|first3=Constantino|last4=Francisco López|first4=Ahinara|last5=Bello Bugallo|first5=Pastora M.|date=2023-01-01|title=Sources, sinks and transformations of plastics in our oceans: Review, management strategies and modelling|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969722058442|journal=Science of The Total Environment|volume=854|pages=158745|doi=10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158745|issn=0048-9697}}</ref> |

|||

プラスチック汚染は[[:en:_Marine_life|海洋生物]]の生命を危険やがては絶滅の危機に晒している。海洋生態系において、カモメ、クジラ、魚、カメなどの海洋生物は、'''プラスチック廃棄物を餌と誤認し、その結果、胃がプラスチックで満たされ、餓死または病死することがほとんど'''である。被害に遭った生物たちは生き残ったとしても裂傷、感染症、泳ぐ能力の低下、内部の傷害などを被る。<ref>{{Cite web |date=November 17, 2021 |title=Marine Plastic Pollution. |url=https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/marine-plastic-pollution. |access-date=December 14, 2021 |website=IUCN}}</ref> 世界中で、クジラ、イルカ、ネズミイルカ、アシカなど年間10万匹の海洋哺乳類がプラスチック汚染の結果として死亡している。<ref>{{Cite web |date=July 1, 2021 |title=Plastic in Our Oceans Is Killing Marine Mammals |url=https://www.wwf.org.au/news/blogs/plastic-in-our-oceans-is-killing-marine-mammals. |access-date=December 14, 2021 |website=WWF |archive-date=17 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211217025818/https://www.wwf.org.au/news/blogs/plastic-in-our-oceans-is-killing-marine-mammals. |url-status=dead}}</ref> 実例として2018年にタイの南部でくじらの胃から80袋以上の袋が見つかったり、プラスチック片を誤飲して胃がいっぱいになって餓死するウミドリやプラスチック製漁網が魚や鳥に絡まったなどがある。<ref>{{Cite web |title=ゼロから分かるプラスチック問題と海洋汚染 |url=https://www.greenpeace.org/japan/explore/plastic/ |website=www.greenpeace.org |access-date=2023-11-07 |language=ja}}</ref> |

|||

さらにプラスチック廃棄物は、海洋の小型無脊椎動物ですら摂食するほどの[[マイクロプラスチック]]に分解され、食物連鎖を汚染する。マイクロプラスチックはその小ささのため発生源も特定できず、'''開放海洋環境から除去するのは非常に困難で、集積していく一方である'''。<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=De Matteis|first1=Alessandro|last2=Turkmen Ceylan|first2=Fethiye Burcu|last3=Daoud|first3=Mona|last4=Kahuthu|first4=Anne|date=2022|title=A systemic approach to tackling ocean plastic debris|journal=Environment Systems and Decisions|volume=42|issue=1|pages=136–145|language=en|doi=10.1007/s10669-021-09832-0|issn=2194-5403|s2cid=238208588|doi-access=free}}</ref> [[:en:_Environment_Agency|Environment Agency]]は、マイクロプラスチックが毎年数十万の海の生物の死を引き起こすとしている。<ref>https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411982/Assessing_the_impact_of_exposure_to_microplastics_in_fish_report.pdf Assessing the impact of exposure to microplastics in fish. </ref> |

|||

=== 人の健康への悪影響 === |

|||

[[File:Refuse Recycling site.jpg|thumb|ゴミがリサイクルされている場所、ガーナ]] |

|||

[[フタル酸エステル]]、[[ビスフェノールA]](BPA)、[[ポリ臭化ジフェニルエーテル|ポリ臭素化ジフェニルエーテル]](PBDE)などプラスチック製造に添加剤として使用される化合物は大気や水中に放出することでも環境を汚染するが、人に対するこれら化合物の暴露はそれらを添加剤として含む[[マイクロプラスチック]]を人が取り込むことによっても起こる。屋内の換気および空調システムを通じて持続的にダストとして循環しているマイクロプラスチックの吸入は、人がマイクロプラスチックを取り込む主要なルートの1つである。<ref name=":05">{{Cite journal |last1=Kannan |first1=Kurunthachalam |last2=Vimalkumar |first2=Krishnamoorthi |date=2021-08-18 |title=A Review of Human Exposure to Microplastics and Insights Into Microplastics as Obesogens |journal=Frontiers in Endocrinology |volume=12 |page=724989 |doi=10.3389/fendo.2021.724989 |pmid=34484127 |pmc=8416353 |issn=1664-2392|doi-access=free }}</ref> このような環境下でほとんどの人が常にプラスチックの添加剤成分にさらされており、内分泌系や生殖系をいろいろな機序で攪乱しうる。<ref name=":13">{{Cite journal|last1=D'Angelo|first1=Stefania|last2=Meccariello|first2=Rosaria|date=2021-03-01|title=Microplastics: A Threat for Male Fertility|journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health|volume=18|issue=5|pages=2392|doi=10.3390/ijerph18052392|issn=1660-4601|pmc=7967748|pmid=33804513|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

米国では成人の95%が尿中にビスフェノールAが検出可能なレベルであることがある。<ref name="plastics environ health">{{cite journal|last1=North|first1=Emily J.|last2=Halden|first2=Rolf U.|date=1 January 2013|title=Plastics and environmental health: the road ahead|journal=Reviews on Environmental Health|volume=28|issue=1|pages=1–8|doi=10.1515/reveh-2012-0030|pmc=3791860|pmid=23337043}}</ref> ビスフェノールAは: |

|||

* [[甲状腺ホルモン]]系に関連する遺伝子発現を乱し代謝や発育に影響を与える。 |

|||

* [[:en:_Thyroid_hormone_receptor|甲状腺ホルモン受容体(TR)]]の活性を低下させ、これにより[[トリヨードチロニン]]に結合する甲状腺ホルモン結合タンパク質の量が減少し、その結果甲状腺機能低下につながる可能性がある。<ref name="plasticizer" /> |

|||

* [[性ホルモン]]([[アンドロゲン]]と[[エストロゲン]]など)に[[性ホルモン結合グロブリン|結合するグロブリン]]に結合することにより、正常な生理的性ホルモンレベルを妨害することがある。<ref name="plasticizer" /> |

|||

* しばしば抗アンドロゲンまたはエストロゲンとして機能し、性腺の発達と精子の生産に損傷を引き起こしうる。<ref name="plasticizer" /> |

|||

2022年に発表された「[[:en:_Environment_International|Environment International]]」の研究では、対象とした人々の80%の血液中に[[マイクロプラスチック]]が含まれており、'''[[マイクロプラスチック]]が人間の臓器に取り込まれる可能性がある'''ことを示した。<ref>{{cite news |last=Carrington |first=Damian |date=March 24, 2022 |title=Microplastics found in human blood for first time |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/mar/24/microplastics-found-in-human-blood-for-first-time |work=The Guardian |location= |access-date=March 28, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

==== 未知の疾患の可能性 ==== |

|||

2023年、海鳥でではあるが、それまでは未知だったプラスチックだけによって引き起こされる疾患「[[:en:_Plasticosis|プラスチコーシス]]」が発見された。この疾患を患った鳥はプラスチック廃棄物を摂取したことで消化管が損傷し、<ref name=":19">{{Cite web |url=https://amp.theguardian.com/environment/2023/mar/03/plasticosis-new-disease-caused-by-plastics-discovered-in-seabirds|title=New disease caused by plastics discovered in seabirds |date=March 3, 2023 |work=The Guardian |access-date=March 4, 2023}}</ref> 持続的な炎症を起こし、消化、成長、生存に悪影響を被る。<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.nhm.ac.uk/press-office/press-releases/new-disease-caused-solely-by-plastics-discovered-in-seabirds-.html|title=New disease caused solely by plastics discovered in seabirds |date=March 3, 2023 |publisher=Natural History Museum |access-date=March 4, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

== プラスチックの使用削減努力、廃棄物に対する対策と現状 == |

|||

[[File:Plastic household items.jpg|thumb|right|さまざまな種類のプラスチックで作られた家庭用品]] |

|||

[[File:Waste generation per day per capita, September 2018.jpg|thumb|廃棄物の発生量(1 人あたり 1 日あたりのキログラム単位)]] |

|||

2021年のサイエンス誌における初めてのグローバルなプラスチック汚染に関する科学的[[総説論文]]では、合理的な対応策として未使用のプラスチック材料の消費の削減と、プラスチック廃棄物の輸出禁止(輸入国で輸出国より良いリサイクルが実施可能な場合を除く)など、国際的に調整された廃棄物管理戦略とがあると主張している。<ref>{{cite news |title=Is global plastic pollution nearing an irreversible tipping point? |url=https://phys.org/news/2021-07-global-plastic-pollution-nearing-irreversible.html |access-date=13 August 2021 |work=phys.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=MacLeod|first1=Matthew|last2=Arp|first2=Hans Peter H.|last3=Tekman|first3=Mine B.|last4=Jahnke|first4=Annika|date=2 July 2021|title=The global threat from plastic pollution|url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abg5433|journal=Science|volume=373|issue=6550|pages=61–65|language=en|bibcode=2021Sci...373...61M|doi=10.1126/science.abg5433|issn=0036-8075|pmid=34210878|s2cid=235699724}}</ref> |

|||

一部の自治体や企業では、プラスチックボトル水やプラスチック袋など一般的に使用される使い捨てプラスチック製品の使用を禁止している。<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/australia/5778162/Australian-town-bans-bottled-water.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220112/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/australia/5778162/Australian-town-bans-bottled-water.html |archive-date=12 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |title=Australian town bans bottled water |newspaper=[[The Daily Telegraph]] |date=8 July 2009 |access-date=1 August 2013 |author=Malkin, Bonnie}}{{cbignore}}</ref> 一部のNGOはレストランなどを審査し「エコフレンドリー」であると顧客に保証する証明書を交付するなどのプラスチック削減戦略を実施している。<ref>{{Cite web|title=Pledging for a plastic-free dining culture {{!}} Daily FT|url=http://www.ft.lk/environment/Pledging-for-a-plastic-free-dining-culture/10519-691921|access-date=2020-08-22|website=www.ft.lk|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

2022年3月2日、ナイロビで175カ国の代表がプラスチック汚染を終わらせるための法的拘束力のある協定を作成することを誓約した。この協定はプラスチックの[[ライフサイクルアセスメント|ライフサイクル全体に取り組み]]、[[リサイクル]]のみならず[[再使用|'''再利用''']]などの代替案を提案するもので、2024年の年末までにこの協定を考案するための[https://www.unep.org/inc-plastic-pollution 政府間交渉委員会(INC)]が設立された。この協定は循環経済への移行を容易にし温室効果ガスの排出を25%削減すると期待されている。[[国際連合環境計画|UNEP]]の事務局長であるInger Andersenは、この決定を「使い捨てプラスチックに対する地球の勝利」とした。<ref name="unep.org" /><ref>{{cite web |title=End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument* |url=https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/38522/k2200647_-_unep-ea-5-l-23-rev-1_-_advance.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |website=United Nations Environmental Programm |access-date=13 March 2022}}</ref> 総会に先立ち、プラスチック条約に関する国際的な世論が[https://www.plasticfreejuly.org/about-us/ The Plastic Free Foundation]、[[イプソス|Ipsos]]、[[世界自然保護基金|WWF-International]]の協力により調査、分析、報告された。それによれば、調査対象者(28カ国にまたがる2万人以上の成人)の約90%が、グローバルな条約がプラスチック汚染危機への対処に役立つと期待している。<ref name=":15" /> |

|||

=== 生分解性および自発分解性プラスチック === |

|||

{{Further|Sustainable packaging#Alternatives to plastics}} |

|||

[[生分解性プラスチック]]には多くの利点とともに欠点もある。生分解性プラスチックは産業用の[[堆肥化施設]]では分解できても一般家庭の[[堆肥化|堆肥]]では効率的に分解されず、この遅いプロセス中には温暖化ガスの[[メタン]]が放出されるかもしれない。<ref name="plastics environment human health">{{cite journal |last1=Thompson |first1=R. C. |last2=Moore |first2=C. J. |last3=vom Saal |first3=F. S. |last4=Swan |first4=S. H. |date=14 June 2009 |title=Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=364 |issue=1526 |pages=2153–2166 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2009.0053 |pmc=2873021 |pmid=19528062}}</ref> |

|||

自発分解性プラスチックも種々開発されている。これらは[[生体高分子]]性材料ではなく既存のプラスチックと同様に化石燃料由来だが、太陽光中の紫外線や熱などの物理的な要因で分解するのを促進する添加剤を使用して自発分解性を付与したものである。しかしこのタイプのプラスチックは小さな断片には分解するが化学的に更なる小分子までには分解されずマイクロプラスチックの生成を促進するだけで、2023年の時点ではプラスチック汚染対策上有用なものは見いだされていない。<ref name="plastics environment human health" /> 生分解反応を促進する添加剤を[[ポリエチレン]]や[[ポリエチレンテレフタラート|PETポリマー]]に試用してもそれらの生分解を促進することはなく、<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1021/es504258u|pmid=25723056|title=Evaluation of Biodegradation-Promoting Additives for Plastics|journal=Environmental Science & Technology|volume=49|issue=6|pages=3769–3777|year=2015|last1=Selke|first1=Susan|last2=Auras|first2=Rafael|last3=Nguyen|first3=Tuan Anh|last4=Castro Aguirre|first4=Edgar|last5=Cheruvathur|first5=Rijosh|last6=Liu|first6=Yan|bibcode=2015EnST...49.3769S}}</ref> いずれのタイプも自然環境では効率的に分解されるには至っていない。 |

|||

2019年の英国の議会委員会は、新しい種類のプラスチックの廃棄物についての消費者の理解やインフラが不足していることから、堆肥分解性および生分解性プラスチックはむしろ[[海洋汚染]]に寄与する可能性があると結論付けた。たとえばこれらのプラスチックは適切に分解するためには産業用[[堆肥化施設]]に送る必要があるが、廃棄物を[[堆肥化施設]]に届ける適切なインフラは未だ存在しない。<ref name=":3">{{Cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/12/plastic-alternatives-may-worsen-marine-pollution-mps-warn |title=Plastic alternatives may worsen marine pollution, MPs warn |date=12 September 2019 |work=The Guardian |access-date=12 September 2019}}</ref> したがって、堆肥分解性および生分解性プラスチックを市場に導入するよりも、既存のプラスチックの使用量を減らすほうが重要視された。<ref name=":3" /> |

|||

=== 既存プラスチックの分解酵素 === |

|||

{{See also|Category:Organisms breaking down plastic}} |

|||

汚染された場所に生息する微生物は、新しい酵素を進化させることで既存のプラスチックを分解消化できるようになることがある。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yoshida|first=Shosuke|last2=Hiraga|first2=Kazumi|last3=Takehana|first3=Toshihiko|last4=Taniguchi|first4=Ikuo|last5=Yamaji|first5=Hironao|last6=Maeda|first6=Yasuhito|last7=Toyohara|first7=Kiyotsuna|last8=Miyamoto|first8=Kenji|last9=Kimura|first9=Yoshiharu|date=2016-03-11|title=A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate)|url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aad6359|journal=Science|volume=351|issue=6278|pages=1196–1199|language=en|doi=10.1126/science.aad6359|issn=0036-8075}}</ref><ref name="Ong">{{cite journal |last1=Ong |first1=Sandy |title=The living things that feast on plastic |journal=Knowable Magazine {{!}} Annual Reviews |date=24 August 2023 |doi=10.1146/knowable-082423-1|doi-access=free |url=https://knowablemagazine.org/article/food-environment/2023/how-to-recycle-plastic-with-enzymes}}</ref> 2021年の研究ではそのようなプラスチック分解酵素がプラスチック汚染の悪化と相関して進化していることを見出し、17種類の既存プラスチックに対する95種のプラスチック分解酵素についてその進化を追跡し、分解酵素としての可能性のある新規酵素約3万種類を同定した。 <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Zrimec|first=Jan|last2=Kokina|first2=Mariia|last3=Jonasson|first3=Sara|last4=Zorrilla|first4=Francisco|last5=Zelezniak|first5=Aleksej|editor-last=Kelly|editor-first=Libusha|editor2-last=Newman|editor2-first=Dianne K.|date=2021-10-26|title=Plastic-Degrading Potential across the Global Microbiome Correlates with Recent Pollution Trends|url=https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mBio.02155-21|journal=mBio|volume=12|issue=5|language=en|doi=10.1128/mBio.02155-21|issn=2150-7511|pmc=PMC8546865|pmid=34700384}}</ref> しかしこれらの酵素が自然環境下でプラスチック汚染を減少させるほどプラスチックを分解している証拠は2023年現在見いだされていない。<ref>{{cite web |title=Bugs across globe are evolving to eat plastic, study finds |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/14/bugs-across-globe-are-evolving-to-eat-plastic-study-finds |website=The Guardian |language=en |date=14 December 2021 |access-date=2023-11-5}}</ref> |

|||

=== 焼却 === |

|||

医療から発生するプラスチック廃棄物は([[オートクレーブ]]などの前処理を施さない限り)通常の埋め立て処分ができないため[[焼却炉|焼却]]されている。<ref name="plastics environ health" /> 大規模な焼却プラントでは、プラスチック、紙、および他の材料が[[サーマルリサイクル|廃棄物からエネルギー]]を供給する燃料として使用され、合計生産量の約12%が焼却されている。<ref>{{Cite web|title=Our planet is drowning in plastic pollution. This World Environment Day, it's time for a change|url=https://www.unep.org/interactive/beat-plastic-pollution/#:~:text=Because%20right%20now,%20a%20lot,dumps%20or%20the%20natural%20environment.|access-date=2021-03-27|website=www.unep.org}}</ref> [[:en:_Incineration#Gaseous_emissions|焼却プロセスから生じる有害ガス排出]]に関する多くの研究と対策が行われている。 焼却プラスチックは燃焼過程で、[[ダイオキシン類|ダイオキシン]]、[[ポリ塩化ジベンゾフラン]]、[[水銀に関する水俣条約|水銀]]、[[ポリ塩化ビフェニル]]など多くの有害物質を放出し、重大な健康影響と[[大気汚染]]を引き起こすことから、<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last1=Verma|first1=Rinku|last2=Vinoda|first2=K.S.|last3=Papireddy|first3=M.|last4=Gowda|first4=A.N.S.|date=2016-01-01|title=Toxic Pollutants from Plastic Waste – A Review|journal=Procedia Environmental Sciences|volume=35|pages=701–708|language=en|doi=10.1016/j.proenv.2016.07.069|issn=1878-0296|doi-access=free}}</ref> プラスチック廃棄物はこれら有害物質を回収または処理するため特別に設計された施設でのみ焼却することが求められている。 |

|||

=== 炭化 === |

|||

炭化は焼却と異なり、プラスチックの構成成分のうち[[炭素]]原子だけを残して他の成分を気化し[[炭]]として回収するものである。理論上大気中への[[二酸化炭素]]排出量が焼却よりも少ないことから[[地球温暖化]]への悪影響が少なく、リサイクル不可能な廃棄物でも実施できることから、実用的なプラスチック廃棄物処理法として多くの研究が進められ、<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Weldekidan|first=Haftom|last2=Mohanty|first2=Amar K.|last3=Misra|first3=Manjusri|date=2022-11-16|title=Upcycling of Plastic Wastes and Biomass for Sustainable Graphitic Carbon Production: A Critical Review|url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsenvironau.2c00029|journal=ACS Environmental Au|volume=2|issue=6|pages=510–522|language=en|doi=10.1021/acsenvironau.2c00029|issn=2694-2518|pmc=PMC9673229|pmid=36411867}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Chen|first=Shuiliang|last2=Liu|first2=Zheng|last3=Jiang|first3=Shaohua|last4=Hou|first4=Haoqing|date=2020-03-25|title=Carbonization: A feasible route for reutilization of plastic wastes|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969719362461|journal=Science of The Total Environment|volume=710|pages=136250|doi=10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136250|issn=0048-9697}}</ref> ''' '''実際にハワイの海岸漂着プラスチック廃棄物処理への応用が行われた。<ref>{{Cite web |title=ハワイに日本の炭化技術を!漂着ペットボトルを炭化し、資源循環させる - クラウドファンディング READYFOR |url=https://readyfor.jp/projects/monjyu-hawaii |website=readyfor.jp |access-date=2023-11-07 |language=ja}}</ref> 問題となるのは[[ポリ塩化ビニル]]など[[塩素]]を含むプラスチックからは[[塩化水素]]が発生し炭化[[炉]]を腐食し、大気中に排出すると大気汚染につながることであるが、前処理により先に塩素を除去するなどの方法も開発されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Wang|first=Linzheng|last2=Zhang|first2=Rui-zhi|last3=Deng|first3=Ruiqu|last4=Luo|first4=Yong-hao|date=2021-02-22|title=Oxygen-Induced Enhancement in Low-Temperature Dechlorination of PVC: An Experimental and DFT Study on the Oxidative Pyrolysis Process|url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08667|journal=ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering|volume=9|issue=7|pages=2835–2843|language=en|doi=10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08667|issn=2168-0485}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kots|first=Pavel A.|last2=Vance|first2=Brandon C.|last3=Quinn|first3=Caitlin M.|last4=Wang|first4=Cong|last5=Vlachos|first5=Dionisios G.|date=2023-10|title=A two-stage strategy for upcycling chlorine-contaminated plastic waste|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-023-01147-z|journal=Nature Sustainability|volume=6|issue=10|pages=1258–1267|language=en|doi=10.1038/s41893-023-01147-z|issn=2398-9629}}</ref> 処理後に残留する炭は各種用途があり商用化されているものもあり、<ref>{{Cite web |title=株式会社大木工藝 {{!}} 環の知産 |url=http://ohki-techno.com/environment.html#&panel1-3 |website=ohki-techno.com |access-date=2023-11-07}}</ref> 文字通り廃棄物から新たな製品への直接のリサイクルを実現させている。 |

|||

=== 収集、リサイクル、削減 === |

|||

{{Main|Plastic recycling}} |

|||

プラスチック廃棄物を減少させることはリサイクルをサポートし、再利用とともに'''「3R」(削減 <u>r</u>educe、再利用 <u>r</u>euse、リサイクル <u>r</u>ecycle)'''というキーワードで呼ばれる。<ref name="10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04709">{{cite journal|last1=Thushari|first1=G. G. N.|last2=Senevirathna|first2=J. D. M.|date=1 August 2020|title=Plastic pollution in the marine environment|journal=Heliyon|volume=6|issue=8|pages=e04709|language=English|bibcode=2020Heliy...604709T|doi=10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04709|issn=2405-8440|pmc=7475234|pmid=32923712}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Wichai-utcha|first1=N.|last2=Chavalparit|first2=O.|date=1 January 2019|title=3Rs Policy and plastic waste management in Thailand|journal=Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management|volume=21|issue=1|pages=10–22|language=en|doi=10.1007/s10163-018-0781-y|issn=1611-8227|s2cid=104827713}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Mohammed|first1=Musa|last2=Shafiq|first2=Nasir|last3=Elmansoury|first3=Ali|last4=Al-Mekhlafi|first4=Al-Baraa Abdulrahman|last5=Rached|first5=Ehab Farouk|last6=Zawawi|first6=Noor Amila|last7=Haruna|first7=Abdulrahman|last8=Rafindadi|first8=Aminu Darda’u|last9=Ibrahim|first9=Muhammad Bello|date=January 2021|title=Modeling of 3R (Reduce, Reuse and Recycle) for Sustainable Construction Waste Reduction: A Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)|journal=Sustainability|volume=13|issue=19|pages=10660|language=en|doi=10.3390/su131910660|issn=2071-1050|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Zamroni|first1=M.|last2=Prahara|first2=Rahma Sandhi|last3=Kartiko|first3=Ari|last4=Purnawati|first4=Dia|last5=Kusuma|first5=Dedi Wijaya|date=1 February 2020|title=The Waste Management Program Of 3R (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) By Economic Incentive And Facility Support|journal=Journal of Physics: Conference Series|volume=1471|issue=1|pages=012048|language=en|bibcode=2020JPhCS1471a2048Z|doi=10.1088/1742-6596/1471/1/012048|s2cid=216235783|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

ごみ収集の一般的な形態には、[[ごみ収集|路上収集]]とリサイクルセンターへの持ち込みがある。米国では人口の87%(2億7300万人)が両方を利用でき、63%(1億9300万人)が路上収集を利用できる。路上収集では指定された種類のプラスチックの廃棄物をリサイクル回収箱に入れて清掃会社によって運搬する。<ref name="name" /> ほとんどの路上収集では[[ポリエチレンテレフタラート|PET]]および[[高密度ポリエチレン|HDPE]]は回収可能である。<ref name="name1" /> リサイクルセンターは米国の68%の人口(2億1300万人)がリサイクル可能な廃棄物を持ち込める。<ref name="name">{{cite web|title=AF&PA Releases Community Recycling Survey Results|url=http://www.paperrecycles.org/news/press_releases/2010_community_survey_results.html|access-date=3 February 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120602132040/http://paperrecycles.org/news/press_releases/2010_community_survey_results.html|archive-date=2 June 2012}}</ref> 収集されたプラスチックはリサイクル原料としての製品価値を高めるため、単一プラスチック材料ごとに仕分けされるための[[:en:_Materials_recovery_facility|材料回収施設(MRF)]]またはハンドラーで仕分けられ、再生業者への配送コストを削減するために包装される。<ref name="name1">{{cite web |url=http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/doc.asp?CID=1571&DID=5972 |title=Life cycle of a plastic product |work=[[American Chemistry Council|Americanchemistry.com]] |access-date=3 September 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100317004747/http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/doc.asp?CID=1571&DID=5972 |archive-date=17 March 2010 }}</ref> |

|||

プラスチックの種類によりリサイクル率は異なる。米国では2017年の総プラスチックリサイクル量270万トンであったが、同時に2,430万トンのプラスチックが埋立地に投棄され、リサイクル率はわずか8.4%であった。一部の種類のプラスチックは回収しやすく他の種類よりも多くリサイクルされる。2017年ではHDPEボトルが31.2%、PETボトル・ジャー29.1%のがリサイクルされた。<ref name="epa_plastic_2017">{{cite web |title=Facts and Figures about Materials, Waste and Recycling |url=https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data |publisher=United States Environmental Protection Agency |access-date=12 January 2020 |date=2017}}</ref> |

|||