トランプ政権

この記事は英語版の対応するページを翻訳することにより充実させることができます。(2022年6月) 翻訳前に重要な指示を読むには右にある[表示]をクリックしてください。

|

ドナルド・トランプ政権 (ドナルド・トランプせいけん、英: Presidency of Donald Trump、Donald Trump administration)は、2016年のアメリカ大統領選挙を経て[1]、2017年1月21日にドナルド・トランプが大統領に就任することで発足したアメリカの政権を指す[2]。トランプ政権ではマイク・ペンスが副大統領を務めた[3]。

2016年選挙

[編集]

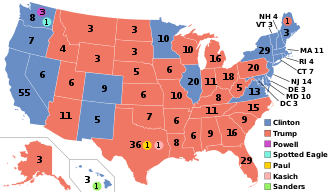

2016年11月8日に共和党の候補者であったドナルド・トランプとマイク・ペンスインディアナ州知事が、民主党の候補者であったヒラリー・クリントン元国務長官とティム・ケインバージニア州上院議員を破り、勝利した。トランプは選挙人投票で304票を獲得し、クリントンの227票を上回り、当選した。しかし、得票数では約290万票も多くクリントンが獲得しており、得票数ではクリントンがトランプを上回っていた。これにより、トランプはアメリカ史上5人目となる、一般投票で敗北しながら大統領となった人物となった[4]。同時に行われた議会選挙では、共和党は上下両院における多数派を維持した。

移行期間、就任式、最初の100日間

[編集]

2017年1月20日に、第45代アメリカ合衆国大統領に就任した。宣誓就任式でトランプに大統領就任の宣誓をさせたのは、最高裁判所長官のジョン・ロバーツである[5]。17分間の就任演説で、現代アメリカ社会の暗澹たる現状のイメージを描いた。都市犯罪によって引き起こされたアメリカの殺戮を終わらせるとし「このアメリカ内部の殺戮は、まさにここで、たった今、終わります」と述べた。また、海外流出によって「我々は、この国の富と力と自信が地平線の向こうで衰退していく間に、よその国々を金持ちにしてきたのです」と訴えた[6][7]。国家戦略として、「アメリカ第一主義(アメリカ・ファースト)」を掲げた[5]。アメリカ史上最大規模の1日限りの抗議運動「ウィメンズマーチ」は、トランプの就任式翌日に開催された。トランプとその政策や見解に対する反対意見によって推進された[8]。

政権

[編集]トランプ政権は、過去例のない職員の入れ替わりが特徴的であった。2018年初めまでに、ホワイトハウスの高官の43%が入れ替わっていた[9]。政権の最初の2年半での離職率が、過去5人の大統領の任期全体の離職率よりも高かった[10]。

2019年10月までに、政治任命者のうち、14人に1人は元ロビイストであった。任期3年目未満の時点で、バラク・オバマ前大統領の最初の6年間の任期中よりも4倍以上のロビイストを任命した[11]。

ジェフ・セッションズ(アラバマ州上院議員)を司法長官[12]、スティーブン・ムニューシン(銀行家)を財務長官[13]、ジェームズ・マティス(退役海兵隊大将)を国防長官[14]、レックス・ティラーソン(エクソンモービルの最高経営責任者)を国務長官[15]に任命するなどした。

内閣

[編集]大統領選から数日後、トランプは共和党全国委員会委員長のラインス・プリーバスを大統領首席補佐官に指名した[16]。また、ジェフ・セッションズを司法長官に指名した[17]。

2017年2月に、トランプは閣僚人事の発表を行い、国家情報長官と中央情報局長官を閣僚レベルに昇格させた。オバマ政権が2009年に閣僚レベルに昇格させた大統領経済諮問委員会委員長は、閣僚から外された。トランプ政権の閣僚は24人となり、オバマ政権の23人、ジョージ・W・ブッシュ政権の21人を上回った[18]。

2017年2月13日に、トランプは、マイケル・フリン国家安全保障問題担当大統領補佐官がペンス副大統領に対し、セルゲイ・キスリャクロシア連邦駐米大使との通信内容について虚偽の説明を行ったことを理由に解任した。後に、ロシア連邦駐米大使との接触などに関して連邦捜査局に偽証した罪を認めた[19]。

2017年7月、国土安全保障長官を務めていたジョン・フランシス・ケリーが、ラインス・プリーバスに代わり大統領首席補佐官に就任した[20]。

リーダーシップスタイル

[編集]トランプは、側近や部下からは、その言動や振る舞いが「幼稚」であると評されることが多かった[21]。大統領日報のような詳細な文書を読むことを避け、代わりに口頭での説明を受けることを好んだ[22][23]。情報機関職員は機密情報を説明する際、トランプの注意を引くために、名前と肩書を繰り返し述べていたと報道されている[24][25]。情報収集手段として1日に8時間ものテレビ視聴を行っていたことで知られている。特に、FOXニュースの番組の「Fox & Friends」や「Hannity」などを好んで視聴していた。これらの番組で取り上げられる主張を、トランプは早朝のツイートなどの公式声明で時折繰り返した[26][27][28]。諜報分析がトランプの考えや公的発言と矛盾した場合に怒りを露わにしたと報道されている。2人の情報機関職員は、上司から「大統領の公的発言と矛盾する情報は提供しないように」との指示を受けていたと述べている[25]。

経営手法として混乱を招き、スタッフの間で士気の低下と政策上の混乱を引き起こしていた、と報道されている[29][30]。第115回米国議会は、共和党が両院を制していたにもかかわらず、トランプの妥協姿勢欠如が招いた議会機能不全により、特筆すべき立法実績を残すことができなかった[31]。著名な大統領歴史家であるドリス・カーンズ・グッドウィンは、「謙虚さ、過ちを認める能力、失敗の責任を負い、そこから学ぶ能力、共感力、回復力、協調性、人々と互いに理解し合う能力、非生産的な感情を抑制する能力」などといった、アメリカの指導者にとって不可欠な資質を欠いていたと指摘している[32]。

2018年1月に、ニュースサイトのアクシオスは、トランプの執務時間が通常午前11時から午後6時頃であると報道した。これは、大統領任期当初に比べて開始時刻が遅く、終了時刻が早くなっている。トランプの自由な時間(行政時間として記されている)への希望を叶えるため、会議数は減らされていた[33]。2019年に、アクシオスは、トランプの2018年11月7日から2019年2月1日までのスケジュールを公開し、分析した結果、トランプは午前8時から午後5時までの時間の約60%をいわゆる行政時間に費やされていたことを明らかにした[34]。

虚偽または誤解を招く発言

[編集]

トランプは、演説、発言、ツイートにおいて、学者、ファクトチェッカー、評論家によって虚偽であると特定された発言が、歴代アメリカ大統領の中で前代未聞の規模である[38][39]。トランプの虚偽発言を「政治的アイデンティティを特徴付けるもの」であると、ザ・ニューヨーカーは表現した[40]。一方、トランプの虚偽発言は、共和党の政治顧問のアマンダ・カーペンターによって「ガスライティングの戦術」であると指摘されている[41]。トランプ政権は客観的な真実という概念を否定し[42]、政治運動や政権は「ポスト真実」[43]と「超オーウェルリアン」[44]であると評されている。トランプは自分の主張と矛盾する連邦機関のデータを無視し、伝聞や逸話、そして偏ったメディアの疑わしい主張を引用し、現実を否定し(トランプ自身の発言を含め)、虚偽が指摘されると責任逃れの言動をとった[45]。

トランプ政権の1年目に、ワシントン・ポストのファクトチェックチームはトランプを「今まで遭遇した中で最も事実に疎い政治家」と評し、「大統領の虚偽発言のペースと量が多すぎて、とても追いつけない」と述べた[46]。ワシントン・ポストの報道によると、トランプは任期中、3万件を超える虚偽または誤解を招く発言を行ったことがあり、初年度の1日平均6件から、最終年度には1日39件へと増加された[47]。経済と雇用、メキシコとアメリカの壁、税制改革などについて、最も頻繁に虚偽または誤解を招く主張を行っていた[48]。過去の政権[48]、犯罪、テロ、移民、ロシアとミュラー調査、ウクライナ調査、移民、新型コロナウイルスパンデミック等、他の話題に関する虚偽の声明も行っていた[35]。政府高官は、メディアに対して度々虚偽、誤解を招く、または歪曲された発言をしていた[49][50]。そのため、メディア側としては公式発表を信用することが困難となった[49]。

法の支配

[編集]ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、トランプが2016年の共和党指名候補になる直前に、「政治的立場にかかわらず、法律の専門家の間では、トランプの発言は憲法修正第1条、三権分立、法の支配といった憲法の基礎原則を軽視する姿勢を示しているという意見で一致している」と報じた。同紙は、「保守派やリバタリアン系の多くの法律学者は、トランプが大統領になれば憲法危機が起こると警告している」と付け加えた[51]。

国内政策

[編集]農業政策

[編集]トランプ政権の貿易関税と農産物価格の低迷により、農家は数十年ぶりの危機に直面した[52]。

歴史的評価と世論

[編集]シエナカレッジ研究所がトランプの就任1年後に行った大統領ランキング第6回調査において、歴代大統領の中で3番目に低い評価を受けた[53]。C-SPANの2021年の大統領歴史家調査において、歴代大統領の中で4番目に低い総合評価を受け、道徳的権威と行政能力の項目では最下位となった。最も高評価の項目は国民に対する説得力であり、32位となった[54]。

トランプが大統領に就任してから、アメリカの民主主義評価は著しく低下した[55]。

脚注

[編集]- ^ “【米大統領選2016】トランプ氏が勝利 クリントン氏が敗北認める”. BBCニュース (2016年11月9日). 2022年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ “【写真で見る】 トランプ米大統領就任式”. BBCニュース (2017年1月21日). 2022年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ “副大統領候補にはマイク・ペンス氏が指名される見通し”. www.cnn.co.jp. 2022年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ DeSilver, Drew (December 20, 2016). "Trump's victory another example of how Electoral College wins are bigger than popular vote ones". Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Fahrenthold, David; Rucker, Philip; Wagner, John (January 20, 2017). "Donald Trump is sworn in as president, vows to end 'American carnage'". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (January 21, 2018). "'American carnage': Donald Trump's vision casts shadow over day of pageantry". The Guardian. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ “【米政権交代】 「アメリカ第一」 トランプ新大統領の就任演説 全文と和訳”. BBCニュース (2017年1月21日). 2024年2月13日閲覧。

- ^ Waddell, Kaveh (January 23, 2017). "The Exhausting Work of Tallying America's Largest Protest". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Keith, Tamara (March 7, 2018). “White House Staff Turnover Was Already Record-Setting. Then More Advisers Left”. NPR March 16, 2018閲覧。

- ^ Joung, Madeleine (July 12, 2019). “Trump Has Now Had More Cabinet Turnover Than Reagan, Obama and the Two Bushes”. Time October 26, 2019閲覧。.

- ^ Mora, David (October 15, 2019). “We Found a "Staggering" 281 Lobbyists Who've Worked in the Trump Administration”. ProPublica. October 15, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric (November 18, 2016). “Jeff Sessions, as Attorney General, Could Overhaul Department He's Skewered”. The New York Times December 19, 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Former US banker Steve Mnuchin confirms he will be US treasury secretary”. BBC News. (November 30, 2016) November 30, 2016閲覧。

- ^ Lamothe, Dan (December 1, 2016). “Trump has chosen retired Marine Gen. James Mattis for secretary of defense”. The Washington Post December 1, 2016閲覧。

- ^ Shear, Michael D.; Haberman, Maggie (December 12, 2016). “Rex Tillerson, Exxon C.E.O., chosen as Secretary of State”. The New York Times December 26, 2016閲覧。

- ^ Shear, Michael; Haberman, Maggie; Rappeport, Alan (November 13, 2016). “Donald Trump Picks Reince Priebus as Chief of Staff and Stephen Bannon as Strategist”. The New York Times November 14, 2016閲覧。

- ^ Stokols, Eli (November 18, 2016). “What Trump's early picks say about his administration”. Politico November 18, 2016閲覧。

- ^ Walker, Hunter (February 8, 2017). “President Trump announces his full Cabinet roster”. Yahoo! News February 9, 2017閲覧。

- ^ Goldman, Adam; Mazzetti, Mark (May 14, 2020). “Trump White House Changes Its Story on Michael Flynn”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 May 20, 2020閲覧。

- ^ Bender, Bryan; Hesson, Ted; Beasley, Stephanie (July 28, 2017). “How John Kelly got West Wing cleanup duty”. Politico July 29, 2017閲覧。

- ^ Drezner, Daniel W. (2020). The Toddler-in-Chief. University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226714394.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-71425-7

- ^ Leonnig, Carol D.; Harris, Shane; Jaffe, Greg (February 9, 2018). “Breaking with tradition, Trump skips president's written intelligence report and relies on oral briefings”. The Washington Post November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Graham, David A. (January 5, 2018). “The President Who Doesn't Read”. The Atlantic. November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (May 17, 2017). “Donald Trump will only read intelligence reports if he is mentioned in them, White House sources claim”. The Independent. November 7, 2021閲覧。

- ^ a b Walcott, John (February 5, 2019). “'Willful Ignorance'. Inside President Trump's Troubled Intel Briefings”. Time November 7, 2021閲覧。.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Thrush, Glenn; Baker, Peter (December 9, 2017). “Inside Trump's Hour-by-Hour Battle for Self-Preservation”. The New York Times November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (April 22, 2018). “Watch President Trump repeat Fox News talking points”. CNNMoney. November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Gertz, Matthew (January 5, 2018). “I've Studied the Trump-Fox Feedback Loop for Months. It's Crazier Than You Think.”. Politico. November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ “Trump's Chaos Theory for the Oval Office Is Taking Its Toll” (March 1, 2018). November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Umoh, Ruth (March 13, 2018). “Business professors discuss Donald Trump's chaotic management style”. CNBC. November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Binder, Sarah (2018). “Dodging the Rules in Trump's Republican Congress”. The Journal of Politics 80 (4): 1454–1463. doi:10.1086/699334. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ^ Stewart, James B. (January 10, 2019). “Why Trump's Unusual Leadership Style Isn't Working in the White House”. November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Swan, Jonathan (January 7, 2018). “Trump's secret, shrinking schedule”. Axios. February 12, 2019閲覧。

- ^ McCammond, Alexi; Swan, Jonathan (February 3, 2019). “Insider leaks Trump's "Executive Time"-filled private schedules”. Axios February 5, 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b Kessler, Glenn; Kelly, Meg; Rizzo, Salvador; Lee, Michelle Ye Hee (January 20, 2021). “In four years, President Trump made 30,573 false or misleading claims”. The Washington Post. オリジナルのJanuary 20, 2021時点におけるアーカイブ。 November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Dale, Daniel (June 5, 2019). “Donald Trump has now said more than 5,000 false things as president”. Toronto Star. オリジナルのOctober 3, 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Dale, Daniel [@ddale8] (2020年3月9日). "Trump is averaging about 59 false claims per week since @tarasubramaniam and I started counting at CNN on July 8, 2019. Here's our internal day-by-day chart through March 1, 2020. (The Ukraine-impeachment October was the worst month during that period.) t.co/1mmDAW94sw t.co/BErpdjG6PK" (英語). 2022年9月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。X(旧Twitter)より2023年1月15日閲覧。

- ^ McGranahan, Carole (April 2017). “An anthropology of lying: Trump and the political sociality of moral outrage”. American Ethnologist 44 (2): 243–248. doi:10.1111/amet.12475. オリジナルのJanuary 26, 2021時点におけるアーカイブ。 June 13, 2020閲覧. "Donald Trump is different. By all metrics and counting schemes, his lies are off the charts. We simply have not seen such an accomplished and effective liar before in U.S. politics. ... Stretching the truth and exaggerating is a key part of Trump's repertoire."

- ^ Segers, Grace (June 12, 2020). “Washington Post fact checker talks about Trump and the truth”. CBS News November 11, 2021閲覧. "Glenn Kessler, the chief writer for the "Fact Checker" feature of The Washington Post, says that 'every president lies,' but President Trump is unique in the sheer scale and number of his falsehoods. ... 'What is unique about Trump is that he misleads and says false things and lies about just about everything on a regular basis.'"

- ^ Glasser, Susan (August 3, 2018). “It's True: Trump Is Lying More, and He's Doing It on Purpose”. The New Yorker January 10, 2019閲覧. "for the President's unprecedented record of untruths ... the previous gold standard in Presidential lying was, of course, Richard Nixon ... the falsehoods are as much a part of his political identity as his floppy orange hair and the "Make America Great Again" slogan."

- ^ Carpenter, Amanda (April 30, 2019). Gaslighting America: Why We Love It When Trump Lies to Us. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-274801-0 March 2, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (July 17, 2018). The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-525-57484-2 March 2, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (2018). “Donald Trump and the Politics of Lying”. Post-Truth, Fake News. pp. 89–100. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8013-5_7. ISBN 978-981-10-8012-8

- ^ Peters, Michael A. (2018). “Education in a Post-truth World”. Post-Truth, Fake News. pp. 145–150. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8013-5_12. ISBN 978-981-10-8012-8

- ^ Jamieson, Kathleen Hall; Taussig, Doron (2017). “Disruption, Demonization, Deliverance, and Norm Destruction: The Rhetorical Signature of Donald J. Trump”. Political Science Quarterly 132 (4): 619–650. doi:10.1002/polq.12699 March 2, 2019閲覧。.

- ^ Ye, Hee Lee Michelle; Kessler, Glenn; Kelly, Meg (October 10, 2017). “President Trump has made 1,318 false or misleading claims over 263 days”. The Washington Post November 5, 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Trump's false or misleading claims total 30,573 over 4 years”. The Washington Post. (January 24, 2021)

- ^ a b Kessler, Glenn; Rizzo, Salvador; Kelly, Meg (December 16, 2019). “President Trump made 18,000 false or misleading claims in 1,170 days”. The Washington Post November 11, 2021閲覧。

- ^ a b Dawsey, Josh (May 15, 2017). “Trump's trust problem”. Politico May 16, 2017閲覧。

- ^ Tsipursky, Gleb (March 2017). “Towards a post-lies future: fighting "alternative facts" and "post-truth" politics”. The Humanist. March 2, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 4, 2016). “Donald Trump Could Threaten U.S. Rule of Law, Scholars Say”. The New York Times November 18, 2018閲覧。

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra (March 11, 2019). “Trump budget proposes steep subsidy cuts to farmers as they grapple with crisis”. Reuters. November 7, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Cummings, William (February 13, 2019). “Survey of scholars places Trump as third worst president of all time”. USA Today October 19, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Choi, Joseph (June 30, 2021). “Trump ranked fourth from worst in C-SPAN's 2021 presidential rankings”. The Hill July 1, 2021閲覧。

- ^ “Democracy for All? V-Dem Annual Democracy Report 2018”. Varieties of Democracy Project (V-DEM). pp. 5–6, 16, 19–22, 27–32, 36, 46, 48, 54, and 56 (May 28, 2018). January 17, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。February 20, 2019閲覧。