フランス語史

この項目「フランス語史」は途中まで翻訳されたものです。(原文:en:History of French) 翻訳作業に協力して下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴、翻訳のガイドラインも参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2011年12月) |

この記事はフランス語関係の記事の一部である。 | |||

フランス語(ふらんすご、仏: français)は俗ラテン語の子孫であるロマンス語の一つである。フランス北部で話されていたガロ=ロマンス方言が次第に変化して生じた。

言語史を述べる場合、記述を「外的な歴史」と「内的な歴史」に区分することが通例であり、本稿もそれに従う。外的な歴史 external history は民族・社会・政治・技術などの変化が言語に及ぼす影響を論じるものであり、内的な歴史 internal history は自発的要因から言語が被る音韻や文法の変化を論じるものである。

外的な歴史[編集]

属州ガリア[編集]

紀元前58年から52年にガイウス・ユリウス・カエサルによって征服されるまでは、フランスの大部分は古代ローマ人によってガリア人と呼ばれていたケルト語を話す人々と、ガリア北海岸のベルガエ人によって占められていた。フランス南部にも、ピレネー山脈と地中海西部に沿って広がっていたイベリア人、地中海東部のリギュール人、マルセイユやアンティーブといったギリシャ植民地、ヴァスコン人、アクィタニア人、南西部の原始バスク人など、複数の異なる言語、文化が存在していた。[要出典]

ガリアのケルト人が多数の方言を持つゴール語を話していたことはある程度証明されており、アルプスの南端ではレポント語も話されていた。俗ラテン語から進化したフランス語はこれらのゴール語の影響も受けており、そのうち特に顕著なのは連音現象(リエゾン、アンシェヌマン、子音弱化)とアクセントの無い音節の欠落である。ゴール語起源の統語上の習慣としては、強調を意味する接頭辞re-の使用(例えば、luire「かすかに光る」とreluire「光る」のように、ラテン語の口語における接頭辞re-は、ゴール語のro-やアイルランド語のro-と同じように使われている。)強調構文、発音を表すための前置詞変化、oui「はい」や、それに似た言葉の意味の拡がりなどが挙げられる。

フランス語と近隣のフランス語方言、および密接に関連した言語には、今も200程度のゴール語起源の単語が残っており、それらのほとんどは民衆の生活に関連したものである。その一例として下記が挙げられる。

- 地理(bief「河口、水車用の水路」、combe「くぼ地」、grève「砂浜」、lande「荒地」)

- 植物の名前(berl「セリ科植物」、bourdaine「セイヨウイソノキ」、chêne「コナラ」、bouleau「カバノキ」、corme「ナナカマド」、garzeau「ムギセンノウ」、if「イチイ」、velar/vellar「カキネガラシ」)

- 野生生物(alouette「ヒバリ」、barge「オグロシギ」、belette「コエゾイタチ」、loche「ドジョウ」、pinson「アトリ」、vanneau「タゲリ」)

- 田舎および農場生活(boue「泥」、cervoise「大麦のビール」、char「荷馬車」、charrue「犂」、glaise「ローム」、gord「魚を取る立て網」、 jachère「休耕地」、javelle「刈り穂積み」、marne「泥灰土」、mouton「羊」、raie「畑の畝」、sillon「畝溝」、souche「切り株」、 tarière「ねじ錐」、tonne「大樽」)

- 一般的な動詞(braire「どなる、わめく」、changer「変える」、craindre「恐れる、心配する」、jaillir「人、もの、感情などが噴出する」)[1]

その他のケルト語の単語は直接ではなくラテン語を通して取り入れられ、そのうちのいくつかはラテン語において一般的に使用される単語となった(例えば、béton「コンクリート」、braies「膝丈のズボン」、 chainse「チュニック」、daim「ダマシカ」、 étain「スズ」、glaive「両刃の剣」、manteaux「コート」、vassal「農奴、召使い」など。)ラテン語は都市部の上流階級の間で貿易、公務、教育などに使用される目的で急速に広まったが、地方の領主や農民たちにとってはほとんど、もしくは全く社会的価値がなかったため、ラテン語が地方にまで普及するのは4、5世紀後のことになる。結果的にラテン語が普及したのは、都市集中型の経済から農場中心型の経済への移行、農奴制など、王政時代の社会的要因によるものと考えられている。

フランク族[編集]

3世紀ごろから、西ヨーロッパは北と東からのゲルマン人部族による侵略を受け、そのうちのいくつかの部族はガリアに定住した。これらの部族のうち、フランス語の歴史において大きな影響を与えたのは、フランス北部に定住したフランク族、現在のドイツ・フランス国境付近のアレマンニ族、ローヌ渓谷のブルグント族とスペインのアキテーヌ地域に定着した東ゴート族である。ゲルマン部族の言語はそれぞれの地域で話されていたラテン語に非常に大きな影響を与え、発音(特に母音の音素)と文法両方を変化させた。 また、ゲルマン人の言語からラテン語に対して、新しい言葉が大量に持ち込まれた。(ドイツ語に起源があるフランス語の単語一覧)現在のフランス語(方言は除く)の語彙のうち、どの程度の割合でゲルマン語起源の語が存在するかは議論が分かれており、500語(1%)[2]程度(ゴート語やフランク語などの古ゲルマン語からの借用語)[3]から、15%(ゴート語、フランク語、スカンジナビア語、オランダ語、ドイツ語と英語など、現代までの全てのゲルマン諸語からの影響を考えた場合)[4]まで開きがある。 もしラテン語や他のロマンス諸語を通じて流入した語彙を含めるなら、この割合はさらに増える可能性がある(注意:アカデミー・フランセーズによると、英語に由来するフランス語の言葉は5%しかない)

- Françaisという言語名自体は、古フランス語のfranceis/francesc(中世ラテン語のfranciscusを参照のこと)やゲルマン語のfrankiscから来ていて、「french」や「frankish」は、Frank(「自由人」)から来ている。Franksは3世紀にラテン語でFranciaとなったFranko(n)である土地に関係している(当時は現在のベルギーやオランダの一部であるガリア・ベルギカの地であった)。Gauleという名称も、フランク語の*Walholant(「ローマ人/ガウル人の土地」)から来ている。

- 社会構造に関連する用語や表現数語(baron/baronne, bâtard, bru, chambellan, échevin, félon, féodal, forban, gars/garçon, leude, lige, maçon, maréchal, marquis, meurtrier, sénéchal)

- 軍事用語(agrès/gréer, attaquer, bière [「担架」], dard, étendard, fief, flanc, flèche, gonfalon, guerre, garder, garnison, hangar, heaume, loge, marcher, patrouille, rang, rattraper, targe, trêve, troupe)

- フランク語などのゲルマン諸語に由来する色名(blanc/blanche, bleu, blond/blonde, brun, fauve, gris, guède)

- 共通する単語の他の例に、abandonner, arranger, attacher, auberge, bande, banquet, bâtir, besogne, bille, blesser, bois, bonnet, bord, bouquet, bouter, braise, broderie, brosse, chagrin, choix, chic, cliché, clinquant, coiffe, corroyer, crèche, danser, échaffaud, engage, effroi, épargner, épeler, étal, étayer, étiquette, fauteuil, flan, flatter, flotter, fourbir, frais, frapper, gai, galant, galoper, gant, gâteau, glisser, grappe, gratter, gredin, gripper, guère, guise, hache, haïr, halle, hanche, harasser, héron, heurter, jardin, jauger, joli, laid, lambeau, layette, lécher, lippe, liste, maint, maquignon, masque, massacrer, mauvais, mousse, mousseron, orgueil, parc, patois, pincer, pleige, rat, rater, regarder, remarquer, riche/richesse, rime, robe, rober, saisir, salon, savon, soupe, tampon, tomber, touaille, trépigner, trop, tuyauや硬音のg(例:gagner, garantie, gauche, guérir)や有音のh(haine, hargneux, hâte, haut)で始まる多くの単語がある。[5]

- -ard(フランク語のhard由来:canard, pochard, richard)や-aud(フランク語のwald由来:crapaud, maraud, nigaud)、-ais/-ois(フランク語の-isc由来:marais, Anglais, berlinois)、-an/-and(古い接尾辞由来-anc, -enc:paysan, Flamand, tisserand)で終わるものは、フランスでは非常に一般的な姓の接辞である。

- -ange(英語の-ing、ドイツ語の-ung:boulange/boulanger, mélange/mélanger, vidange/vidanger)で終わるものは、指小辞語-onであり、多くの動詞は、-ir(affranchir, ahurir, choisir, honnir, jaillir, lotir, nantir, rafraîchir, ragaillardir, tarir)で終わる。

- -quin(低フランク語-kin由来:casaquin, bouquin, brodequin, mannequin, quinquin(したがって歌謡P'tit quinquin, ramequin, ribaudequin)で終わる単語

- mésentente, mégarde, méfait, mésaventure, mécréant, mépris, méconnaissance, méfiance, médisanceのような接頭辞mé(s)-

- フランク語のfir-やfur-(ドイツ語のver-や英語のfor-を参照されたい)由来のforbannir, forcené, forlonger, (se) fourvoyerなどの接頭辞for-, four-。ラテン語のforis由来の「~の外側」や「~の上部」を表す古フランス語のfuersと合わさったもの。ラテン語のforisは古典ラテン語では接頭辞には用いなかったが、ゲルマン侵攻後の中世ラテン語では接頭辞として見られる。

- ラテン語のin-(英語のinやon、intoに当たる)由来の接頭辞en-やem-は、フランク語の*in-や*an-の影響で、ラテン語では見られなかった新たな用法を得た。通常は強調文や完了文で用いられる単語:emballer, emblaver, endosser, enhardir, enjoliver, enrichir, envelopperなど

- The syntax shows the systematic presence of a subject pronoun in front of the verb, as in the Germanic languages: je vois, tu vois, il voit, while the subject pronoun is optional – function of the parameter pro-drop – in the other Romance languages (as in veo, ves, ve).

- 疑問文における主語と述語の倒置。これはゲルマン諸語の特徴であり、フランス語以外の主要なロマンス諸語には見られない(Vous avez un crayon.→Avez-vous un crayon?(鉛筆を持っていますか。))。

- 名詞の前に形容詞を置くのは、ゲルマン諸語の特徴で、他の主要なロマンス諸語よりもフランス語で一般的で、ときにはそれが必須となっている(belle femme, vieil homme, grande table, petite table)。任意の場合は、その意味が変わってくる(grand homme(「偉人」)とle plus grand homme(「最も偉大な人」)/homme grand(「背の高い人」)とl'homme le plus grand(「最も背の高い人」)、certaine chose/chose certaine)。ワロン語では《形容詞+名詞》の語順は、古フランス語のように一般的な規則である。

- ゲルマン諸語の対応する単語から借用したり原形になっている単語が数語ある(bienvenue, cauchemar, chagriner, compagnon, entreprendre, manoeuvre, manuscrit, on, pardonner, plupart, sainfoin, tocsin, toujours)。

850年になるとネウストリアでさえゲルマン語は役人の第二公用語になり下がってしまった。…10世紀の間に口語としては西アウストラシアでもネウストリアでも完全に消滅したといえるだろう。[6]

ノルマン人と低地諸国由来の語[編集]

西暦1204年に、ノルマンディー公国はフランス王国領となった。そして、古ノルド語[7]に起源を持つ約150の語がノルマン語よりフランス語に取り入れられた。それらの多くは海や航海に関係する語である。

abraquer, alque, bagage, bitte, cingler, équiper(装備する), flotte, fringale, guichet, hauban, houle, hune, mare, marsouin, mouette, quille, ras, siller, touer, traquer, turbot, vague, varangue, varech. 他は農業や日々の生活に関係がある:accroupir, amadouer, bidon, bigot, brayer, brette, cottage, coterie, crochet, duvet, embraser, fi, flâner, guichet, haras, harfang, harnais, houspiller, marmonner, mièvre, nabot, nique, quenotte, raccrocher, ricaner, rincer, rogue.

同様に、オランダ語からの借用語も、主に貿易や海事についてのものが多いが、必ずしもそれらに関係する言葉ばかりではない。

affaler, amarrer, anspect, bar(すずきの類), bastringuer, bière(ビール), blouse(上っ張り), botte, bouée, bouffer, boulevard, bouquin, cague, cahute, caqueter, choquer, diguer, drôle, dune, frelater, fret, grouiller, hareng, hère, lamaneur, lège, manne, mannequin, maquiller, matelot, méringue, moquer, plaque, sénau, tribord, vacarme, 低ドイツ語の単語のように:bivouac, bouder, homard, vogue, yole, この時代の英語のように:arlequin(イタリア語arlecchino < ノルマン語hellequin < 古英語*Herla cyning), bateau, bébé, bol (sense 2 ≠ bol < Lt. bolus), bouline, bousin, boxer, cambuse, cliver, chiffe/chiffon, drague, drain, est, équiper (to set sail), gourmet, groom, héler, interlope, merlin, nord, ouest, pique-nique, potasse, rade, rhum, sloop, sonde, sud, turf, yacht.

オイル語[編集]

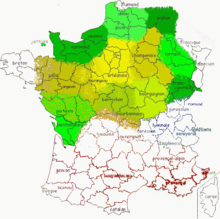

中世イタリアの詩人ダンテはその著書「俗語論」でロマンス諸語は「はい」(現在の標準フランス語ではoui)と言うのに用いる単語によって3つの類例に分類できるとした。 Nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil(ocと言う人もいれば、siと言う人もいれば、oïlと言う人もいる) ラテン語のhoc ille「それはそれ」に由来するoïlは北フランスを、ラテン語のhoc「それ」に由来するocは南フランスを、ラテン語のsic「従って」に由来するsiはイタリア半島やイベリア半島を占めた。現代の言語学者は、概して現代語でouèとなるリヨン周辺のフランスにおける第3類「アルピタン語」を加えている。

フランスの北のガロ・ロマンス語群(ピカルディ語やワロン語、フランシアン語のようなオイル語)は、フランクの侵略者が話していたゲルマン語派から影響を受けた。クローヴィス1世の時代からフランク族は北ガウルを越えて支配地域を拡大した。時を超えて、フランス語はパリやイル=ド=フランス地域圏周辺で見出されるオイル語や(フランシアン理論)オイル語全てに見出される共通の特徴を基礎にした公用語から(リングワ・フランカ理論)発展した。

「はい」としてocやòcを用いる言語であるオック語は、フランスの南や北スペインの言語群である。ガスコーニュ語やプロヴァンス語のようなこの言語は、相対的にフランク語の影響をほとんど受けていない。

中世にはフランスの方言における他の言語群の影響が見られた。

主にsiという単語を取得したオイル語に由来する近代フランス語は、スペイン語やカタルーニャ語(sí)やポルトガル語(sim)、イタリア語(sì)における「はい」の同種の形態から否定疑問文に対する否定の主張や返答を否定するのに用いた。この語はケベック・フランス語に一部残っていて、フランス語話者は主に北西フランスからの移民に起源がある。

4世紀から7世紀にかけて、コーンウォールやデヴォン、ウェールズからのブリソン諸語を話す人々が、通商やアングロ・サクソンのイングランド侵攻から逃れるためにイギリス海峡を横断した。アルモリカに自身の国を建国した。言語はフランス語のbijouやmenhirを与えて最近の世紀にブルトン語になった。しかしこの変化は一方通行ではなく、後にフランス語が組み込んだavenのようなブルトン語の単語は、フランス語のhavreから派生したものである。

ガイウス・ユリウス・カエサルの時代から証明されているように、中世前期のロマンス諸語の拡大によって衰退したとはいえ、南西フランスのノヴェンポプラニアにはバスク語と近縁の言語を話す非ケルト系の人々が暮らしていた。彼らはガロンヌ川とピレネー山脈の間の地域で話すラテン語を基礎とした言語に影響し、結局ガスコーニュ語と呼ばれるオック語の方言となった。その影響はboulbèneやcargaisonのような単語に見られる。

スカンディナヴィアのヴァイキングが9世紀以降にフランスに侵攻し、ノルマンディーと呼ばれることになる地域の大半に自国を建国した。ノルマン語は古ノルド語やその方言に大いに影響されたが、ノルマン人はそこではオイル語を話すことにした。海運(mouette, crique, hauban, huneなど)や農業に関連する多くのフランス語を残した。

1066年のイングランド征服後、ノルマン人の言語は、アングロ=ノルマン語へと成長した。フランス語の影響した英語の使用がイングランド社会を通じて拡大した時代までに、アングロ=ノルマン語は征服から百年戦争までのイングランドの支配階級や商業の言語として使われた[8]。

この頃にアラビア語から多くの借用語が、主に中世ラテン語やイタリア語、スペイン語を通じて間接的にフランス語に入ってきた。高級品(élixir, orange)や香辛料(camphre, safran)、貿易品(alcool, bougie, coton)、科学(alchimie, hasard)、数学(algèbre, algorithme)に関する単語があった。北アフリカにフランスの植民地が拡大するようになると、フランス語はアラビア語から直接単語を借用した(例:toubib)。

中世フランス語から現代フランス語[編集]

1300年頃までについては、さまざまなオイル諸語をまとめて古フランス語(ancien français)として扱うことがある。現存するフランス語最古の文章は842年のストラスブールの誓約である。古フランス語はシャルルマーニュの騎士や十字軍の英雄を詠った武勲詩の成立とともに文語となっていった。

行政機関として初めてフランス語を公用語として採用したのはイタリア北西部のヴァッレ・ダオスタで、1536年のことであったが、これはフランスによるフランス語公用語化に3年先立つものである[9]。1539年のヴィレル=コトレ勅令でフランソワ1世はフランス語を行政と宮廷で用いる公用語とし、それ以前に用いられていたラテン語を追放した。公的機関で用いるべき標準語として使用を強制されたことと、曲用体系を失ったことをもって、オイル語のこの方言は古フランス語と区別される中世フランス語(moyen français)とされている。1550年にはフランス語文法について最初に記述したルイ・メグレのTretté de la Grammaire françaiseが出版されている。現代フランス語で700語を数える、美術(scenario、piano)・嗜好品・食品などを表すイタリア語起源の語彙がこの時期に持ち込まれた[10]。

16世紀に始まった統一化・規範化・純化が行われた後の、17世紀から18世紀にかけてのフランス語を古典フランス語(français classique)とすることがあるが、17世紀以降現代までのフランス語を単に現代フランス語(français moderne)とすることも多い。

1634年にリシュリュー枢機卿によってアカデミー・フランセーズが創設され、フランス語の純化と維持を目的とする公的機関が誕生した。定員40名のアカデミー・フランセーズ会員は les immortels (不死者)として知られている。この二つ名は、ときおりそう誤解されることがあるものの、アカデミー会員の任期が終身であることに由来するのではなく(ただし会員の任期は実際に終身であるが)、リシュリューの定めたアカデミーの紋章に À l'immortalité ([フランス語の]不滅[のため]に)と記されていることによる。今日においても、アカデミー・フランセーズは健在であり、フランス語の監視と外来語・外来表現の置き換えに寄与している。そうした置き換えの最近の例には、software に対する logiciel、packet-boat に対する paquebot、riding-coat に対する redingote などがある。ただし computer に対する ordinateur はアカデミーによる造語ではなく、IBMの依頼を受けた言語学者の手になるものである(この間の経緯は fr:ordinateur を参照のこと)。

17世紀から19世紀にかけては、フランスは欧州屈指の大国であったため、啓蒙思想の影響力も相俟ってフランス語は欧州の知識階級のリンガ・フランカとなり、特に美術、文学、外交分野で崇敬を受けた。プロイセンのフリードリヒ2世やロシアのエカチェリーナ2世などはただフランス語で会話や読み書きができただけでなく、たいへん長じていた。ロシアやドイツ諸国、スカンジナビア諸国の宮廷でも公用語ないし主要言語としてフランス語が用いられ、自民族の言語は農民の言語とみなされ退けられた。

17世紀と18世紀には、フランス語は南北アメリカ大陸において自らの占める位置を恒久的なものとした。ヌーヴェル・フランス(北米のフランス領)の入植者がどの程度フランス語を話すことができたかについては学術上議論が存在する。入植者のうち、おそらくフランス語を話したであろうパリ地方出身者は全体の15%に満たず(なお女性入植者の25%はパリ地方出身であり、多くが「王の娘」であった。男性入植者のうちパリ地方出身者は5%)、それ以外の入植者はおおむね、標準フランス語を母語としないフランス北西部・西部の出身であった。これらの入植者のどれだけが第2言語としてフランス語を理解できたかはよくわかっておらず、また彼らの圧倒的多数はオイル諸語のいずれかを母語としていたが、フランス語を第2言語として習得していない場合に、フランス語とオイル諸語の類似からどの程度までフランス語話者と意思疎通ができたかもはっきりとはわかっていない。いずれにせよ、フランスからの入植者グループのすべてが言語的に統一されたことが(この過程がフランス本土、大西洋航路上、カナダ上陸後のいずれにおけるものであったかはともかく)多数の史料から徴され、その結果17世紀末には当時の全「カナダ人」が母語としてフランス語(王のフランス語)を話したが、これはフランス本土の言語的統一が達成されるよりはるかに早いものである。カナダにおけるフランス語はパリにおけるものと同じくらい良いフランス語であるというのがかつての定評であった。現在、南北アメリカ大陸におけるフランス語の話者数は約1000万人を数えるが、これにはフランス語系のクレオール諸語(全体で同じく1000万ほどの話者人口を持つ)は含まない。

アカデミー・フランセーズの創設や公教育の普及、数世紀にわたる政府による管理、メディアの発達によって、統一された公用語としてのフランス語は堅固なものへと作りあげられてきたが、今日でもアクセントや語彙における地域差は大量に残存している。フランス語の「一番良い」発音はトゥーレーヌ(広義のパリ盆地南西部でトゥールを擁する)のものであろうという評があるが、このような価値判断は問題に満ちており、近代化以降人々が次第に特定の地域で一生を過ごさないようになっていったこと、全国メディアが重要性を増していったことに由来している。個々の「地域的」アクセントが将来どうなっていくのか多くは予見しがたい。1789年のフランス革命とナポレオン帝国の後に成立した、国民国家としてのフランスは、もっぱらフランス語を使用させることを通じてフランス人を統合した。このことについて英国の歴史家エリック・ホブズボームは、「フランス語は、「フランス」という概念の本質といえるものであり、にもかかわらず、1789年にはフランス人の50%はまったくフランス語を話すことができず、「まともに」話せたのは12~13%でしかなかった。実際のところ、オイル語圏でさえも、中心的地域の外では都市部を除いてふつうフランス語は話されておらず、その都市部でも、郊外(faubourgs)では常に話されていたわけではなかった。北仏でも南仏同様に、ほとんど誰もフランス語など話さなかった」[11]と述べている。ホブズボームは、ナポレオンによって導入された徴兵制と、1880年代の公教育法の果たした役割を強調している。両者はフランスの多様な集団を混ぜ合わせナショナリズムの鋳型へと流し込むことで、各人が共通の国家の一員であるという意識をもったフランス国民を作りあげたが、一方でさまざまなパトワ(方言や少数言語)はどんどん根絶されていった。

現代の問題[編集]

現在、フランスでは、フランス語の保存と英語からの影響(フラングレも参照)に関して、特に国際的なビジネス、科学、大衆文化の分野で議論がある。 フランスではフランス語の保存のための法律がある。例えば、印刷物の広告と看板においては、外国語表現を含む表現はフランス語への翻訳を同時に掲載しなければならず、またラジオ上で放送されるフランス語の楽曲の歌詞は、ある割合(最低40%)のフランス語を含まなければならない。

かつてフランス語はヨーロッパでの国際言語であり、17世紀から20世紀半ばまで国際的な外交言語だった。しかし、第二次世界大戦後、アメリカ合衆国が国際的な超大国となったことにより、以前フランス語が占めていた国際言語の地位は英語に取って代わられた。 その転機は第一次世界大戦の講和条約であるヴェルサイユ条約にあり、ヴェルサイユ条約は英語とフランス語両方で書かれた。 フランスに本社を置く国際的な大企業において、フランス国内での業務でさえ英語を使う場合が数は少ないものの増加している。また国際的な認知を得るためには、フランスの科学者は国外のジャーナルへ英語で論文を書く必要がある。想像できる通り、これらの傾向は少なからぬ反発を招いている。 2006年3月のEUサミットにおいて当時のシラク大統領は、フランス人実業家エルネストアントワーヌ・セリエールが英語で演説を始めた際に、サミットを退出した[12]。2007年2月には、フォーラム・フランコフォニー・インターナショナルはフランスにおける英語の"言語的ヘゲモニー"に対する抗議の組織化を始め、フランス人労働者がフランス語を仕事のために使う権利の支援を行っている[13]。

しかし、フランス語を学ぶ人は英語に次いで世界で2番目に多い。また、特にアフリカなど、ある地域における共通語となっていることもある。ヨーロッパ外における生きた言語としてのフランス語は、混合物となっている。東南アジアで形成されたいくつかの旧フランス植民地では、フランス語の遺産はほぼ絶滅している。フランスの領土であった西インド諸島、南太平洋のフランス領ポリネシアでは、この言語はクレオール言語や方言、またピジン言語に変化した。[要出典]その一方で、多数のフランス植民地ではフランス語を公用語として採用し、またフランス語話者の総数は増加している。これはアフリカで顕著である。

カナダの行政区ケベック州においてはこの言語は成功を収め、今日、この行政区の人口の80%が話者となっている[14]。1970年代からのディファレント・ロウと呼ばれる法律、これによりフランス語の保存は行政やビジネス、教育の場で確実なものとなった。例をあげるならばBill 101は、ある子の両親がフランス語で勉強するために英語を用いる学校へ通学しなかった場合、その子供全員に恩恵を与えるものである。このようにケベックでは、英語や非フランス語がフランス語にとって代わることを防止している。こうした代替の最も大きな例は北アメリカであった。努力もまたなされており、例として「ケベック州フランス語評議会」では、ケベックで話されるフランス語の派生をより均一なものとし、また同様に、ケベック・フランス語の特殊性も保存している。

フランスの移民はアメリカ合衆国、オーストラリア、また南アフリカへ行われた。しかし、これら移民たちの子孫は同化し、彼らのうちのごく少数がフランス語を話している。アメリカ合衆国ではルイジアナ州(CODOFIL)、またニューイングランド地方とメイン州の一部で言語保存の努力が進行中である。[要出典]

内的な歴史[編集]

概説[編集]

| 語形 (「歌う」) |

ラテン語 | 古フランス語 | 現代フランス語 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 綴り | 発音 | 綴り | 発音 | |||

| 不定詞 | cantāre | ⟨chanter⟩ | tʃãnˈtæɾ | ⟨chanter⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈte | |

| 過去分詞 | cantātum | ⟨chanté(ṭ)⟩ | tʃãnˈtæ(θ) | ⟨chanté⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈte | |

| 現在分詞 | cantandō | ⟨chantant⟩ | tʃãnˈtãnt | ⟨chantant⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈtɑ̃ | |

| 直説法現在 | 一人称単数 | cantō | ⟨chant⟩ | ˈtʃãnt | ⟨chante⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t |

| 二人称単数 | cantās | ⟨chantes⟩ | ˈtʃãntǝs | ⟨chantes⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t | |

| 三人称単数 | cantat | ⟨chante(ṭ)⟩ | ˈtʃãntǝ(θ) | ⟨chante⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t | |

| 一人称複数 | cantāmus | ⟨chantons⟩ | tʃãnˈtũns | ⟨chantons⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈtɔ̃ | |

| 二人称複数 | cantātis | ⟨chantez⟩ | tʃãnˈtæts | ⟨chantez⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈte | |

| 三人称複数 | cantant | ⟨chantent⟩ | ˈtʃãntǝ(n)t | ⟨chantent⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t | |

| 接続法現在 | 一人称単数 | cantem | ⟨chant⟩ | ˈtʃãnt | ⟨chante⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t |

| 二人称単数 | cantēs | ⟨chanz⟩ | ˈtʃãnts | ⟨chantes⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t | |

| 三人称単数 | cantet | ⟨chant⟩ | ˈtʃãnt | ⟨chante⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t | |

| 一人称複数 | cantēmus | ⟨chantons⟩ | tʃãnˈtũns | ⟨chantions⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈtjɔ̃ | |

| 二人称複数 | cantētis | ⟨chantez⟩ | tʃãnˈtæts | ⟨chantiez⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈtje | |

| 三人称複数 | cantent | ⟨chantent⟩ | ˈtʃãntǝ(n)t | ⟨chantent⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t | |

| 命令形 | 二人称単数 | cantā | ⟨chante⟩ | ˈtʃãnt | ⟨chante⟩ | ˈʃɑ̃t |

| 二人称複数 | cantāte | ⟨chantez⟩ | tʃãnˈtæts | ⟨chantez⟩ | ʃɑ̃ˈte | |

フランス語はおそらくロマンス諸語の中で最も徹底したラテン語からの音声的な変化が起こった言語である。似た変化は北イタリアの方言、たとえばリグーリア州の方言にも見られるが、多くの他のロマンス諸語は、音声的にはフランス語より明らかに保守的である。音声的にはスペイン語や特にイタリア語が最もラテン語に近く、ポルトガル語やオック語、カタルーニャ語とルーマニア語では、ラテン語の発音が中程度保存されている。

フランス語のなかでも、古フランス語と現代語の間では莫大な音変化が見られる。にも係わらず綴りの変化は僅かであり、その結果として現代の綴りと発音には大きな違いが生じている。特に大きな変化として次のようなものが挙げられる。

- ほとんどの語末子音の消失

- それに続く語末の/ǝ/の消失。多くの新たな語末子音が現れる原因になっている。

- 古いアクセント体系の崩壊。

- 母音の発音における重大な変容、特に鼻母音

こうした変化は、綴りの上では全く現れていない。

| 文字 | 古典ラテン語 | 俗ラテン語 | 原始西ロマンス諸語 | 前期古フランス語 (12世紀前半を通じて) |

後期古フランス語 (12世紀後半から) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 閉鎖 | 開放 | 閉鎖 | 開放 | ||||

| A(短) | /a/ | /a/ | ⟨a⟩ /a/ | ⟨e,ie⟩ /æ,iə/ | ⟨a⟩/a/ | ⟨e,ie⟩ /ɛ,jɛ/ | |

| A(長) | /aː/ | ||||||

| AE | /ai/ | /ɛ/ | ⟨e⟩ /ɛ/ | ⟨ie⟩ /iə/ | ⟨e⟩ /ɛ/ | ⟨ie⟩ /jɛ/ | |

| E(短) | /e/ | ||||||

| OE | /oi/ | /e/ | /e/ | ⟨e⟩ /e/ | ⟨ei⟩ /ei/ | ⟨oi⟩ /oi/>/wɛ/ | |

| E(長) | /eː/ | ||||||

| I(短) | /i/ | /ɪ/ | |||||

| Y(短) | /y/ | ||||||

| I(長) | /iː/ | /i/ | ⟨i⟩ /i/ | ⟨i⟩ /i/ | ⟨i⟩ /i/ | ⟨i⟩ /i/ | |

| Y(長) | /yː/ | ||||||

| O(短) | /o/ | /ɔ/ | ⟨o⟩ /ɔ/ | ⟨uo⟩ /uə/ | ⟨o⟩ /ɔ/ | ⟨ue⟩ /wɛ/>/ø/ | |

| O(長) | /oː/ | /o/ | /o/ | ⟨o⟩ /o/ | ⟨ou⟩ /ou/ | ⟨o(u)⟩ /u/ | ⟨eu⟩ /eu/>/ø/ |

| U(短) | /u/ | /ʊ/ | |||||

| 長音のU | /uː/ | /u/ | ⟨u⟩ /y/ | ⟨u⟩ /y/ | ⟨u⟩ /y/ | ⟨u⟩ /y/ | |

| AU | /aw/ | /aw/ | ⟨o⟩ /ɔ/ | ⟨o⟩ /ɔ/ | ⟨o⟩ /ɔ/ | ⟨o⟩ /ɔ/ | |

後期のラテン語(例えばロマンス諸語全体の祖語である前期共通ロマンス語)における意味深い変化は、明らかに古フランス語に影響を及ぼし、古典ラテン語の母音を再構築している。ラテン語には長短それぞれのA、E、I、O、U10個の短母音とAE、OE、AU、人によってはUIの3つ(または4つ)の二重母音があった。 [注釈 1] 表に示した通り俗ラテン語では、二重母音AEとOEは共に/e/に合流した。AUは当初は維持され、当初の/o/が更なる変更の犠牲になると/o/に変化した。

従って母音の長さによる古典ラテン語の10母音体系は、母音の音素的性質の違いによる体系に変化した。そのためアクセントのある音節の強勢は、古典ラテン語より俗ラテン語で強く発音されることになった。アクセントのある音節の音に更に変化をもたらす一方で、このことはあまり明瞭ではないアクセントのない音節をもたらすことになった。

古フランス語の音体系は他のロマンス諸語よりも激しく変化した。母音の破壊は、派生した言語のそれぞれに異なる結果をもたらしたが、西ロマンス祖語(ここではロマンス祖語)では一般に起きたことであり、ラテン語のfocu(m)(「炉辺」の語源)は、イタリア語のfuocoやルーマニア語やカタルニア語のfoc、スペイン語のfuego、フランス語のfeuになった(全て「火」を意味している)。しかし古フランス語では音素は他のロマンス語より更に大きく変化し、ラテン語から引き継いだ7母音のうちでは/i/だけが本質的に変わっていない。強勢のある音節では、

- ラテン語のE(短母音)は、ロマンス祖語の/ɛ/となり、古フランス語のieになった。ラテン語のmel「蜂蜜」>古フランス語miel

- ラテン語O(短母音)>ロマンス祖語/ɔ/>古フランス語uo。/ɔ/ > cor > cuor「心臓」

- ラテン語ē>ロマンス祖語/e/>古フランス語ei。habēre > aveir「持つ」。この単語は後にavoirのように多くの単語で/oi/となった。

- ラテン語ō>ロマンス祖語/o/>古フランス語ou。flōre(m) > flour「花」

- ラテン語の開音節の/a/>(恐らく/æ/の段階を経て)古フランス語/e/。mare > mer「海」

この変化も北部イタリアのガロ・イタリック方言を特徴づけている(ボローニャ語の[mɛːr]参照)。

ラテン語のAUは、/ɔ/や/o/と運命を共にせず、こうした変化がロマンス祖語に影響を与えている時代には維持された。ラテン語のaurumは古フランス語のor「金」となり、*œurや*ourとはならなかった。

子音に影響を与える変化も、古フランス語ではすっかり浸透していた。古フランス語は残りの俗ラテン語と同様、語末のmは脱落した。この音はラテン語の格にとって基本であったため、脱落はラテン語の総合的な統語論が頼る区別を均し、語順に基礎を置く多くの孤立した統語論を適合させた。また、古フランス語では強勢に続く多くの子音をも失った。ラテン語petra(m)>ロマンス祖語 */peðra/>古フランス語pierre(スペイン語のpiedra参照)(「石」)

ラテン語の/u/は古フランス語では、現代フランス語で「u」と書く唇音/y/になった。

環境によっては/oi/は依然現代フランス語ではoiと書く/e/になった。前期古フランス語ではこの音は前の母音に強勢のある/ói/と書いた通りに発音した。後に強勢は/oé/となる前は/oí/と最後に移った。この音は様々に異なるオイル語に発展したが(生き残った言語のほとんどは、/we/と発音を維持した)、実際のフランス語は、方言のような/wa/を維持した。現代フランス語のfrançaisやFrançoisの姉妹語は、この方言的な様態の混合を見せている。

古フランス語のある時点において続く鼻音を伴う母音は、鼻音化し始めた。最後の鼻子音が失われるのはそれ以後であるが、現代フランス語を特徴づける鼻母音は、この時代に現れた。

母音現況表[編集]

下記の表は、西ロマンス語の強勢のある音節の7母音(/a/, /ɛ/, /e/, /i/, /ɔ/, /o/, /u/)から始まる俗ラテン語の母音の最も重要な現況を示している。母音は最も重要な環境と共に異なる環境でそれぞれ発展した。

- 「開」音節(たいていは子音が一つ続く)では、ほとんどの母音は二重母音か逆に修正された。

- 硬口蓋音が続く音節では、硬口蓋音の前に/i/が(通常二重母音として)現れ、その後組み合わさった方法で徐々に発展した。様々な口蓋音の基があった。古典ラテン語/jj/(例:pēior「より悪い」)、母音が続く短い/e/や/i/が由来の/j/が続く子音(例:balneum「風呂桶」、palātium「宮殿」)、/e/や/i/が続く/k/や/g/(例:pācem「平和」、cōgitō「私は考える」)、/a/が続いたり/a/、/e/、/i/の後に来る/k/や/g/(例:plāga「負傷」)、母音の後の/kl/、/kr/、/ks/、/kt/、/gl/、/gn/、/gr/のような/k/や/g/に始まる子音連続(例:noctem「夜」、veclum < vetulum「古い」、nigrum「黒」)

- 硬口蓋音の後の音節では、硬口蓋音の後に/i/が二重母音を作りながら現れる。硬口蓋音は記述した手法によっては増えることがある。加えて間の母音が失われることで次の子音と繋がりを持つ前の/j/に由来することもある(例:medietātem>ロマンス祖語/mejjeˈtate/>ガロ・ロマンス語/mejˈtat/(強勢のない母音の喪失)>フランス祖語/meiˈtʲat/(口蓋音化)>古フランス語/moiˈtjɛ/>moitié /mwaˈtje/「半分」。

- 鼻音を伴う音節(/n/や/m/が続く)、鼻母音が増大する。鼻音節は逆に開音節で起こる変化の多くを抑制し、代わりに母音が増える傾向がある。後に母音が続かなければ続く/n/や/m/は削除され、鼻母音は減少したが、/n/や/m/が残れば、母音が減少することなく鼻音は失われた。このことは男性形のfin/fɛ̃/と女性形のfine/fin/のような重大な分化をもたらした。

- 閉音の/s/が続く音節(例:他の子音が続く/s/)。古フランス語ではこの/s/は長母音と共にその後失われた/h/に非口腔音化された。この長母音は長らく残り、今もbette/bɛt/「フダンソウ」に対するbête(嘗ては/bɛːt/)「家畜」(<bēstiam)のような交替と共に後のサーカムフレックスが起こりsに表れている。時に長さを変えることで母音の質に違いを持たせた(例:mal/mal/「悪い」に対するmâle(嘗ては/mɑːl(ǝ)/)「牡」(ラテン語のmāsculum>[*/maslǝ/]))。音素上の(音声上でなく)長さは、18世紀までに失われたが、音質の違いは、ほとんど残っている。

- 閉音の/l/が続く音節(例:連音の-lla-は影響を受けないが、別の子音が続く/l/)。/l/は二重母音を形成しながら/u/となり、その際に様々な形に発展した。

- 上記の二つ以上の条件が同時に起きる音節で、一般に複雑に進化した。共通の例は、鼻音や口蓋音の双方が続く音節(例:ラテン語の-neu-、-nea-、-nct-)や口蓋音に続く開音節(例:cēram 「蝋」)、口蓋音の前後に現れる音節(例:jacet 英語の「it lies」)、口蓋音の後に現れ鼻音の前に現れる音節(例:canem 「犬」)である。

強勢のない音節の発展は単純であまり予測できるものではないことに注意されたい。西ロマンス語では/ɛ/, /ɔ/が/e/, /o/に変化して強勢のない母音の音節が5つ(/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/)あったに過ぎない。この音節は強勢のある音節に影響を与える二重母音化や他の複合的な変化の多くを条件としていなかった。このことは強勢のある音節と強勢のない音節の間で辞書的であったり文法上の選択肢を多くもたらした。しかしこの選択肢を平等化する強い傾向が(特に、かつての強勢アクセントが急激に弱まった中期フランス語の初期において)あった。動詞の語形変化では、強勢のない変形は強勢のある音節に組み込まれた例があったが、大抵は現代フランス語において数ある母音全てが強勢のない音節になることで別の形になった。

| ガロ・ロマンス諸語 | 環境 1 | フランス祖語 | 後期古フランス語 | 現代フランス語 | 例 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 基本母音 | |||||

| /a/ | 閉音節 | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | parte > part /paʁ/ 「部分」 |

| 開音節 | /æ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/; /e/+# | mare > mer /mɛʁ/ 「海」、amātum > /aimɛθ/ > aimé /ɛme/ 「愛される」 | |

| 口蓋音+開音節 | /iæ/ | /jɛ/ | /jɛ/; /je/+# | medietātem > /mejtate/ > /meitʲat/ > /moitjɛ/ > moitié /mwatje/ 「半分」、cārum > 古フランス語chier /tʃjɛr/ > cher /ʃɛʁ/ 「親愛な」 | |

| /ɛ/ | 閉音節 | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | septem > sept /sɛt/ 「7」 |

| 開音節 | /iɛ/ | /jɛ/ | /jɛ/; /je/+# | heri > hier /jɛʁ/ 「昨日」、 pedem > pied /pje/ 「足」 | |

| /e/ | 閉音節 | /e/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | siccum > sec /sɛk/ 「乾燥した」 |

| 開音節 | /ei/ | /oi/ > /wɛ/ | /wa/ | pēram > poire /pwaʁ/; vidēre > 前期古フランス語vedeir /vǝðeir/ > 古フランス語vëoir /vǝoir/ > voir /vwaʁ/ 「見える」 | |

| 口蓋音+開音節 | /iei/ | /i/ | /i/ | cēram > cire /siʁ/ 「蝋」、mercēdem > merci /mɛʁsi/ 「感謝する」 | |

| /i/ | 全て | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | vītam > vie /vi/ 「生命」、vīllam > ville > /vil/ 「町」 |

| /ɔ/ | 閉音節 | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/; /o/+#,/s,z/ | portam > porte /pɔʁt/ 「扉」、*sottum, *sottam > sot, sotte /so/, /sɔt/ 「愚かな」、grossum, grossam > gros, grosse /ɡʁo/, /ɡʁos/ 「太った」 |

| 開音節 | /uɔ/ | /wɛ/ | /œ/, /ø/ 2 | novum > neuf /nœf/ 「新しい」、cor > *corem > cœur /kœʁ/ 「心臓」 | |

| /o/ | 閉音節 | /o/ | /u/ | /u/ | subtus > /sottos/ > sous /su/ 「~の下で」、surdum > sourd /suʁ/ 「無言の」 |

| 開音節 | /ou/ | /eu/ | /œ/, /ø/ 2 | nōdum > nœud /nø/ 「ノット」 | |

| /u/ | all | /y/ | /y/ | /y/ | dūrum > dur /dyʁ/ 「難い」、nūllam > nulle /nyl/ 「いいえ」 |

| /au/ | 全て | /au/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/; /o/+/#,s,z/ | aurum > or /ɔʁ/ 「金」、causam > chose /ʃoz/ 「物」 |

| 母音+/n/ | |||||

| /an/ | 閉音節 | /an/ | /ã/ | /ɑ̃/ | annum > an /ɑ̃/ 「年」、cantum > chant /ʃɑ̃/ 「歌」 |

| 開音節 | /ain/ | /ɛ̃n/ | /ɛn/ | sānam > saine /sɛn/ 「健康的な」、amat > aime /ɛm/ 「(誰それは)愛する」 | |

| 後舌閉音節 | /ain/ | /ɛ̃/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | sānum > sain /sɛ̃/ 「健康的な」、famem > faim /fɛ̃/ 「空腹」 | |

| 口蓋音+後舌閉音節 | /iain/ > /iɛn/ | /jɛ̃/ | /jɛ̃/ [jæ̃] | canem > chien /ʃjɛ̃/ 「犬」 | |

| /ɛn/ | 閉音節 | /en/ | /ã/ | /ɑ̃/ | dentem > dent /dɑ̃/ 「歯」 |

| 開音節 | /ien/ | /jɛ̃n/ | /jɛn/ | tenent > tiennent /tjɛn/ 「(彼らは)持つ」 | |

| 後舌閉音節 | /ien/ | /jɛ̃/ | /jɛ̃/ | bene > bien /bjɛ̃/ 「良い」、tenet > tient /tjɛ̃/ 「(誰それは)持つ」 | |

| /en/ | 閉音節 | /en/ | /ã/ | /ɑ̃/ | centum > cent /sɑ̃/ 「百」 |

| 開音節 | /ein/ | /ẽn/ | /ɛn/ | pēnam > peine /pɛn/ 「問題のある」 | |

| 後舌閉音節 | /ein/ | /ẽ/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | plēnum > plein /plɛ̃/ 「十分な」、sinum > sein /sɛ̃/ 「胸」 | |

| 口蓋音+後舌閉音節 | /iein/ > /in/ | /ĩ/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | racēmum > raisin /rɛzɛ̃/ 「葡萄」 | |

| /in/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /in/ | /ĩ/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | quīnque > *cīnque > cinq /sɛ̃k/ 「5」、fīnum > fin /fɛ̃/ 「終わり、見事な、薄い」 |

| 開音節 | /in/ | /ĩn/ | /in/ | fīnam > fine /fin/ 「見事な、薄い」 | |

| /ɔn/ | 閉音節 | /on/ | /ũ/ | /ɔ̃/ | pontem > pont /pɔ̃/ 「橋」 |

| 開音節 | /on/ | /ũn/ | /ɔn/ | bonam > bonne /bɔn/ 「良い」 | |

| 後舌閉音節 | /on/ | /ũ/ | /ɔ̃/ | bonum > bon /bɔ̃/ 「良い」 | |

| /on/ | 閉音節 | /on/ | /ũ/ | /ɔ̃/ | |

| 開音節 | /on/ | /ũn/ | /ɔn/ | dōnat > donne /dɔn/ 「(誰それは)与える」 | |

| 後舌閉音節 | /on/ | /ũ/ | /ɔ̃/ | dōnum > don /dɔ̃/ 「贈り物」 | |

| /un/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /yn/ | /ỹ/ | /œ̃/ > /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | ūnum > un /œ̃/ > /ɛ̃/ 「1」、perfūmum > parfum /paʁfœ̃/ > /paʁfɛ̃/ 「香水」 |

| 開音節 | /yn/ | /ỹn/ | /yn/ | ūnam > une /yn/ 「1」、plūmam > plume /plym/ 「ペン」 | |

| 母音+/s/(子音が続く) | |||||

| /as/ | 閉音節 | /ah/ | /ɑː/ | /ɑ/ | bassum > bas /bɑ/ 「低い」 |

| /ɛs/ | 閉音節 | /ɛh/ | /ɛː/ | /ɛ/ | festam > fête /fɛt/ 「パーティー」 |

| /es/ | 閉音節 | /eh/ | /ɛː/ | /ɛ/ | |

| /is/ | 閉音節 | /ih/ | /iː/ | /i/ | |

| /ɔs/ | 閉音節 | /ɔh/ | /oː/ | /o/ | costam > côte /kot/ 「沿岸」 |

| /os/ | 閉音節 | /oh/ | /uː/ | /u/ | cōnstat > *cōstat > coûte /kut/ 「~はこれくらいかかる」 |

| /us/ | 閉音節 | /yh/ | /yː/ | /y/ | |

| 母音+/l/(/l/+/a/を除く子音が続く) | |||||

| /al/ | 閉音節 | /al/ | /au/ | /o/ | falsum > faux /fo/ 「間違った」、palmam > paume /pom/ 「パーム」 |

| /ɛl/ | 閉音節 | /ɛl/ | /ɛau/ | /o/ | bellum > beau /bo/ (but bellam > belle /bɛl/) 「美しい」 |

| 後舌閉音節 | /jɛl/ | /jɛu/ | /jœ/, /jø/ 2 | melius > /miɛʎts/ > /mjɛus/ > mieux /mjø/ 「より良い」 | |

| /el/ | 閉音節 | /el/ | /ɛu/ | /œ/, /ø/ 2 | capillum > cheveu /ʃǝvø/ 「髪」、*filtir > feutre /føtʁ/ 「フェルト」 |

| /il/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /il/ | /i/ | /i/ | gentīlem > gentil /ʒɑ̃ti/ 「快い」 |

| /ɔl/ | 閉音節 | /ɔl/ | /ou/ | /u/ | follem > fou (but *follam > folle /fɔl/) 「狂った」、colaphum > *colpum > coup /ku/ 「殴打」 |

| 後舌閉音節 | /wɔl/ | /wɛu/ | /œ/, /ø/ 2 | volet > OF vueut > veut 「誰それは欲する」 | |

| /ol/ | 閉音節 | /ol/ | /ou/ | /u/ | pulsat > pousse /pus/ 「誰それは押す」 |

| /ul/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /yl/ | [y] | [y] | |

| 母音+/i/(ガロ・ロマンス諸語の口蓋音要素より) | |||||

| /ai/ | 全て | /ai/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | factum > /fait/ > fait /fɛ/ 「行為」、palātium > palais /palɛ/ 「宮殿」、plāgam > plaie /plɛ/ 「傷」、placet > /plaist/ > plaît /plɛ/ 「誰それは喜ばせる」、paria > paire /pɛʁ/ 「一対」 |

| 口蓋音+ | /iai/ > /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | jacet > gît /ʒi/ 「誰それは横たわる」、cacat > chie /ʃi/ 「誰それは大便をする」 | |

| /ɛi/ | 全て | /iɛi/ | /i/ | /i/ | lectum > /lɛit/ > lit /li/ 「ベッド」、sex > six /sis/ 「6」、pējor > pire /piʁ/ 「より悪い」 |

| /ei/ | 全て | /ei/ | /oi/ | /wa/ | tēctum > /teit/ > toit /twa/ 「天井」、rēgem > /rei/ > roi /ʁwa/ 「王」、nigrum > /neir/ > noir /nwaʁ/ 「黒」、fēriam > /feira/ > foire /fwaʁ/ 「公平な、ショー」 |

| /ɔi/ | 全て | /uɔi/ | /yi/ | /ɥi/ | noctem > /nɔit/ > nuit /nɥi/ 「夜」、hodie > /ɔje/ > hui /ɥi/ 「今日」、coxam > /kɔisǝ/ > cuisse /kɥis/ 「腿」 |

| /oi/ | 全て | /oi/ | /oi/ | /wa/ | buxitam > /boista/ > boîte /bwat/ 「箱」、crucem > croix /kʁwa/ 「交差」 |

| /ui/ | 全て | /yi/ | /yi/ | /ɥi/ | frūctum > /fruit/ > fruit /fʁɥi/ [fʁyi] 「果物」 |

| /aui/ | 全て | /ɔi/ | /oi/ | /wa/ | gaudiam > /dʒɔiǝ/ > joie /ʒwa/ 「楽しみ」 |

| 母音+/ɲ/(/n/+ガロ・ロマンス諸語の口蓋音要素より) | |||||

| /aɲ/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /aiɲ/ > /ain/ | /ɛ̃/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | ba(l)neum > /baɲ/ > /bain/ > bain /bɛ̃/ 「風呂桶」、sanctum > /saɲt/ > /saint/ > saint /sɛ̃/ 「聖なる」 |

| 開音節 | /aɲ/ | /ãɲ/ | /aɲ/ | montāneam > /montaɲ/ > montagne /mɔ̃taɲ/ 「山」 | |

| /ɛɲ/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /ieiɲ/ > /iɲ/ > /in/ | /ĩ/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | |

| /eɲ/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /eiɲ/ > /ein/ | /ẽ/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | pinctum > /peɲt/ > /peint/ > peint /pɛ̃/ 「ペンキを塗った」 |

| 開音節 | /eiɲ/ | /ẽɲ/ | /ɛɲ/ | insigniam > enseigne /ɑ̃sɛɲ/ 「署名する」 | |

| /iɲ/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /iɲ/ > /in/ | /ĩ/ | /ɛ̃/ [æ̃] | |

| 開音節 | /iɲ/ | /ĩɲ/ | /iɲ/ | līneam > ligne /liɲ/ 「線」 | |

| /oɲ/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /oiɲ/ > /oin/ | /wɛ̃/ | /wɛ̃/ [wæ̃] | punctum > /poɲt/ > /point/ > point /pwɛ̃/ 「点」、cuneum > /koɲ/ > /koin/ > coin /kwɛ̃/ 「コーナー」 |

| 開音節 | /oɲ/ | /ũɲ/ | /ɔɲ/ | verecundiam > vergogne /vɛʁɡɔɲ/ 「恥辱」 | |

| /uɲ/ | 閉音節、後舌閉音節 | /yiɲ/ > /yin/ | /ɥĩ/ | /ɥɛ̃/ [ɥæ̃] | jūnium > /dʒyɲ/ > /dʒyin/ > juin /ʒɥɛ̃/ 「6月」 |

^1 環境は次の通りである。

- 「開音節」は精々単子音が続く強勢のある音節である。

- 「閉音節」は別の音節である(強勢がなかったり、二つ以上の子音が続く)。

- 「後舌閉音節」は俗ラテン語(ロマンス祖語)では開音節であったが後に強勢のない母音(通常/e/または/o/が最後に来る)が失われて閉音節になったものである。

- 「口蓋音」は強勢のある母音の前で上記の子音の後に生成される英語の子音の音韻学的歴史上の/j/に起因する口蓋音質が上記の子音にある強勢のある音節である。

^2 /œ/と/ø/は共に現代フランス語に現れ、僅かにミニマル・ペアが見られる(例:jeune /ʒœn/「若い」とjeûne /ʒøn/ [ʒøːn]「断食」)。しかし一般に/ø/は/z/や通常は/t/の前の単語の最後で、/œ/はそれ以外の場所で現れる。

俗ラテン語から西ロマンス祖語まで[編集]

- /s/+子音で始まる単語の前の人工的な短母音/i/の導入:ロマンス語の母音変化で閉音の/e/になる。

- 俗ラテン語の10母音から7母音への縮小:二重母音「ae」と「oe」が、/ɛ/と/e/に縮小し、二重母音/au/が維持された。

- 語末の/-m/の喪失(単音節語を除く、例:現代語rien < rem)

- /h/の喪失

- /ns/ > /s/.

- 単語によっては/rs/ > /ss/(例:dorsum > 現代フランス語dos)、しかしその他の単語では起こっていない(例:ursus > 現代フランス語 ours).

- 語末の/-er/ > /-re/、/-or/ > /-ro/(例:スペイン語cuatro, sobre < quattuor, super)

- 俗ラテン語の強勢のない母音の喪失:/k/、/ɡ/と/r/、/l/に挟まれたインタートニック母音の喪失

- 口蓋化が続く母音接続における/e/と/i/の縮小。語頭の母音の前の/k/や/g/の口蓋音化。

- /kj/は口蓋音化する前に明らかに/kkj/へと二重化している。

- (語頭の母音の前の/dj/、/ɡj/、/ɡ/から派生した)/dʲ/と/ɡʲ/は、/j/になる。

ガロ・イベロ・ロマンス祖語まで[編集]

- /kʲ/と/tʲ/が合わさり、/tsʲ/になった(今も単音とされている)。

- /kt/ > /jt/.

- /ks/ > /js/.

- 最初の二重母音化(限られた方言のみ):/ɛ/と/ɔ/の二重母音化で強勢があり開放シラバスの/ie/と/uo/になった(後に/uo/ > /ue/)。ここでも口蓋音の前の閉音節で起き、後に同化する例も珍しくなかった。peior >> /pejro/ > /piejro/ >> 'pire' 「最悪の」やnocte > /nojte/ > /nuojte/ >> /nujt/ 'nuit'の例があるが、tertiu > /tertsˈo/ >> 'tierz'の例もある。

- 最初の子音弱化(ピレネー山脈周辺の狭い地域では起きなかった):母音に挟まれた子音に関わるチェーンシフト:有声閉音節や無声摩擦音は、有声摩擦音(/ð/、/v/、/j/)になり、無声閉音節は有声閉音節になった。注:/tsʲ/は(/k(eˌi)/や/tj/から来て)単音として発音し、/dzʲ/となったが、/ttsʲ/は(/kk(eˌi)/や/kj/から来て)二重音となり、従って有声音化しなかった。/r/の前の子音は、二重音化し、併せて/pl/ > /bl/となった。語末に/t/や/d/が来ると、次の母音は、二重母音化した。

- /jn/、/nj/、/jl/、/ɡl/は(それぞれ俗ラテン語の/ɡn/、/nɡʲ/、/ɡl/、/kl/に由来し)/ɲ/と/ʎ/にそれぞれ変化する。

- 最初の強勢のない母音の喪失:声調化以前の/a/を除く声調間の(例えば強勢がない音節内部の)母音の喪失。(注:このことは同時に最初の子音弱化として起こり、個々の単語は、調和せずにそれ以前の変化の一例を示している。それ故にmanica > 'manche'となるが、granica > 'grange'となる。carricareは古フランス語の'charchier'か'chargier'になる。)

To Early Old French[編集]

In approximate order:

- Spread and dissolution of palatalization:

- A protected /j/ (not preceded by a vowel), stemming from an initial /j/ or from a /dj/, /ɡj/, or /ɡ(eˌi)/ when preceded by a consonant, becomes /dʒ/.

- A /j/ followed by another consonant tends to palatalize that consonant; these consonants may have been brought together by intertonic loss. (E.g. medietate > /mejetate/ > /mejtʲate/ > 'moitié'. peior > /pejro/ > /piejrʲe/ > 'pire', but impeiorare > /empejrare/ > /empejrʲare/ > /empejriɛr/ > OF 'empoirier' "to worsen".)

- Palatalized sounds lose their palatal quality and eject a /j/ into the end of the preceding syllable, when open; also into the beginning of the following syllable when it is stressed, open, and front (i.e. /a/ or /e/). Hence *cugitare > /kujetare/ > /kujdare/ > /kujdʲare/ >> /kujdiɛr/ OF 'cuidier' "to think". mansionata > /mazʲonada/ > /mazʲnada/ > /majzʲnjɛðə/ > OF 'maisniée' "household".

- /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ (including those from later sources, see below) eject a following /j/ normally, but do not eject any preceding /j/.

- Double /ssʲ/ < /ssj/ and from various other combinations also ejects a preceding /j/.

- Single /dz/ ejects such a /j/, but not double /tts/, evidently since it is a double sound and causes the previous syllable to close; see comment above, under lenition.

- Actual palatal /lʲ/ and /nʲ/ (as opposed to the merely patalized varieties of the other sounds) retain their palatal nature and don't emit preceding /j/. Or rather, palatal /lʲ/ does not eject a preceding /j/ (or else, it is always absorbed, even when depalatalized); palatal /nʲ/ emits a preceding /j/ when depalatalized, even if the preceding syllable is closed, e.g. jungit > *yōnyet > /dʒoɲt/ > /dʒojnt/ 'joint'.

- Palatal /rʲ/ ejects a preceding /j/ as normal, but the /j/ metathesizes when a /a/ precedes, hence operariu > /obrarʲo/ > /obrjaro/ (not [*/obrajro/]) >> 'ouvrier' "worker".

- Second diphthongization: diphthongization of /e/, /o/, /a/ to /ei/, /ou/, /ae/ in stressed, open syllables, not followed by a palatal sound (not in all Gallo-Romance). (Later on, /ei/ > /oi/, /ou/ > /eu/, /ae/ > /e/; see below.)

- Second unstressed vowel loss: Loss of all vowels except /a/ in unstressed, final syllables; addition of a final, supporting /e/ when necessary, to avoid words with impermissible final clusters.

- Second lenition: Same changes as in first lenition, applied again (not in all Gallo-Romance). NOTE: Losses of unstressed vowels may have blocked this change from happening.

- Palatalization of /ka/ > /tʃa/, /ɡa/ > /dʒa/.

- Further vocalic changes (part 1):

- /ae/ > /ɛ/ (but > /jɛ/ after a palatal, and > /aj/ before nasals when not after a palatal).

- /au/ > /ɔ/.

- Further consonant changes:

- Geminate stops become single stops.

- Final stops and fricatives become devoiced.

- /dz/ > /z/, when not final.

- A /t/ is inserted between palatal /ɲ/, /ʎ/ and following /s/ (doles > 'duels' "you hurt" but colligis > *colyes > 'cuelz, cueuz' "you gather"; jungis > *yōnyes > 'joinz' "you join"; filius > 'filz' "son").

- Palatal /ɲ/, /ʎ/ are depalatalized to /n/, /l/ when final or following a consonant.

- In first-person verb forms, they may remain palatal when final due to the influence of the palatalized subjunctives.

- /ɲ/ > /jn/ when depalatalizing, but /ʎ/ > /l/, without a yod. (*veclus > /vɛlʲo/ > /viɛlʲo/ > 'viel' "old" but cuneum > /konʲo/ > 'coin'. balneum > /banjo/ > 'bain' but montanea > /montanja/ > 'montagne'.)

- Further vocalic changes (part 2):

- /jej/ > /i/, /woj/ > /uj/. (placere > /plajdzjejr/ > 'plaisir'; nocte > /nuojt/ > 'nuit'.)

- Diphthongs are consistently rendered as falling diphthongs, i.e. the major stress is on the first element, including for /ie/, /ue/, /ui/, etc. in contrast with the normal Spanish pronunciation.

古フランス語(紀元1100年)まで[編集]

- /f/、/p/、/k/は、語末の/s/, /t/の前では失われた。(debet > ストラスブールの誓い'dift' /deift/ > 古フランス語'doit'.)

- /ei/ > /oi/(鼻音化することで抑制された。下記参照)。

- /wo/ > /we/(鼻音化することで抑制された。下記参照)。

- /a/は/s/の前では異音[ɑ]を発達させた。後にこの音は別個の音素に発達した。下記を参照のこと。

- /θ/と/ð/の喪失。ここから続く母音との/a/の母音接続が起こると、/a/はシュワー/ə/になった。

- 先行する母音の長音化と共に有声音の子音の前の/s/の喪失(/h/を通じて初めて起こった)。長母音接続の新しい組み合わせを導いた。次の段階で更に完成されたと言われる。

- /u/ > /y/.

後期古フランス語(1250年–1300年)まで[編集]

NOTE: Changes here affect oral and nasal vowels alike, unless otherwise indicated.

- /o/ > /u/.

- /l/ before consonant becomes /w/.

- /ue/ and /eu/ > /œ/.

- Rising diphthongs develop when first element of diphthong is /u/, /y/ or /i/, causing the stress to shift to the second element in these cases (hence /yi/ [yj] > [ɥi]).

- /oi/ > /we/. This in turn develops to /ɛ/ in some words, e.g. français; note doublet François. Much later, perhaps in the 17th century, remaining /we/ sounds > /wa/ except in "court" pronunciation. (The /wa/ pronunciation was then stigmatized as "vulgar" until the French Revolution but remaining more or less in use in Quebec.) However, nasalized /wẽ/ was unaffected; hence ModF 'coin' "corner" /kwɛ̃/ not **/kwɑ̃/.

- /ai/ merges into /ɛ/; after this, 'ai' is a common spelling of /ɛ/, regardless of origin. ('è' is a later development.)

- /e/ merges into /ɛ/ in closed syllables.

- /ts/ > /s/, /tʃ/ > /ʃ/, /dʒ/ > /ʒ/.

- Loss of /s/ before any consonant, with lengthening of preceding vowel. This may have begun as early as 900 AD or so, when /s/ before a consonant became /h/. Later on the /h/ vanished with compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel. From borrowings into English, it appeared that this latter stage had already occurred in Old French when the following consonant was voiced but not when it was unvoiced. By the end of Old French, the latter stage was complete and a whole new set of phonemically lengthened vowels developed. These were still marked in writing with an 's', but starting around 1700 were marked instead with circumflex over the vowel (perhaps because actual pronounced /s/ had been reintroduced into that position in certain words, e.g. due to borrowing of learned words from Latin.)

- Development of two low vowels /a/ and /ɑ/. The latter was initially an allophone of /a/ that occurred before /s/ and /z/, and become phonemic when /ts/ merged with /s/. (e.g. Mod. Fr. 'chasse' /ʃas/ "(he) hunts" < [*/cattsa/] < captiat vs. 'châsse' /ʃɑs/ "reliquary, (eyeglass) frame" < [*/cassa/] < capsa "strong box".) Later losses of /s/ produced further minimal pairs, e.g. 'pâte' /pɑt/ "paste" < VL *pasta vs. 'patte' /pat/ "paw" < VL *patta; or 'bas' /bɑ/ "low" < /bas/ < bassum vs. 'bat' /ba/ "(he) beats" < /bat/ < VL *battet < battuet.)

中世フランス語(1500年代)まで[編集]

NOTE: Changes here affect oral and nasal vowels alike, unless otherwise indicated.

- /au/ > /o/.

- /ei/ > /ɛ/.

- Loss of final consonants before a word beginning with a consonant. This produces a three-way pronunciation for many words (alone, followed by a vowel, followed by a consonant), which is maintained to this day in the words 'six' "six" and 'dix' "ten" (and until recently 'neuf' "nine"), e.g. 'dix' /dis/ "ten" but 'dix amis' /diz ami/ "ten friends" and 'dix femmes' /di fam/ "ten women".

- (Around this time, subject pronouns become mandatory.)

(fill in further)

初期現代フランス語(1700年代)まで[編集]

初期現代フランス語(1700年代)まで 音素的に長音化したほとんどの母音の喪失。Standing alone語における語末子音の喪失。このことは多くの単語に対して二様の発音を可能にし (次の単語が母音で始まるか否かに密接に関係)、たとえば、 'nous voyons' /nu vwajɔ̃/ "we see" 'nous avons' /nuz avɔ̃/ "we have" など、今日に至るまで維持されていることが多い。この現象はリエゾンとして知られる。

- 'oi' /we/ > /wa/ (上記を参照 – Through late Old French) or /ɛ/ (e.g. étoit > était – 19th c.).

(fill in further)

現代フランス語(2000年代)まで[編集]

- /r/ becomes uvular sound: trill /ʀ/ or fricative /ʁ/, (replacing the rolled 'r' formerly often used by the clergy).

- Loss of final /ə/. Loss of /ə/ elsewhere unless a sequence of three consonants would be produced (such constraints operate over multiword sequences of words that are syntactically connected).

- Gradual loss of liaison

- Gradual loss of the "ne" in negations, "je n'ai pas" becomes "j'ai pas".

(fill in further)

鼻音化[編集]

Progressive nasalization of vowels before /n/ or /m/ occurred over several hundred years, beginning with the low vowels, possibly as early as c. 900 AD, and finished with the high vowels, possibly as late as c. 1300 AD. Numerous changes occurred afterwards, continuing up through the present day.

The following steps occurred during the Old French period:

- Nasalization of /a/, /e/, /o/ before /n/ or /m/ (originally, in all circumstances, including when a vowel followed).

- Nasalization occurs before, and blocks, the changes /ei/ > /oi/ and /ou/ > /eu/. However, the sequence /ɔ̃i/ occurs because /oi/ has more than one origin, e.g. 'coin' "corner" < cŭneum. The sequences /iẽn/ or /iẽm/, and /uẽn/ or /uẽm/, also occur, but the last two occur in only one word each, in each case alternating with a non-diphthongized variant: 'om' or 'uem' (ModF 'on'), and 'bon' or 'buen' (ModF 'bon'). The version without the diphthong apparently arose in unstressed environments and is the only one that survived.

- Lowering of /ẽ/ and /ɛ̃/ to /ã/; but unaffected in the sequences /jẽ/ and /ẽj/ (e.g. 'bien', 'plein'). The merging of /ẽ/ and /ã/ probably occurred during the 11th or early 12th century, and did not affect Old Norman or Anglo-Norman.

- Nasalization of /i/, /u/, /y/ before /n/ or /m/.

The following steps occurred during the Middle French period:

- Lowering of /ũ/ > /õ/ > /ɔ̃/. (Note that most /ũ/ come from original /õ/, as original /u/ became /y/.)

- Denasalization of vowels before /n/ or /m/ followed by a vowel or semi-vowel. (Note that examples like 'femme' /fam/ "woman" < OF /fãmə/ < fēmina and 'donne' /dɔn/ "(he) gives" < OF /dũnə/ < dōnat, with lowering and lack of diphthongization before a nasal even when a vowel followed, prove that nasalization originally operated in all environments.)

- Deletion of /n/ or /m/ after remaining nasal vowels (i.e. when not protected by a following vowel or semi-vowel). Hence 'dent' /dɑ̃/ "tooth" < [*/dãt/] < OFr 'dent' /dãnt/ < EOFr [*/dɛ̃nt/] < dĕntem.

The following steps occurred during the Modern French period:

- /ĩ/ > /ẽ/ > /ɛ̃/ > [æ̃]. This also affects diphthongs such as /ĩẽ/ > /jẽ/ > /jɛ̃/, e.g. 'bien' /bjɛ̃/ "well" < bĕne; /ỹĩ/ > /ɥĩ/ > /ɥɛ̃/, e.g. 'juin' /ʒɥɛ̃/ "June" < jūnium; /õĩ/ > /wẽ/ > /wɛ̃/, e.g. 'coin' /kwɛ̃/ "corner" < cŭneum. Note also /ãĩ/ > /ɛ̃/, e.g. 'pain' /pɛ̃/ "bread" < panem; /ẽĩ/ > /ɛ̃/, e.g. 'plein' /plɛ̃/ "full (m.s.)" < plēnum.

- /ã/ > /ɑ̃/.

- /ỹ/ > /œ̃/. In the 20th century, this sound has low functional load and has tended to merge with /ɛ̃/.

This leaves only four nasal vowels /ɛ̃/, /ɑ̃/, /ɔ̃/, and /œ̃/, and increasingly only the three /ɛ̃/, /ɑ̃/, /ɔ̃/.

フランス語の基底言語と外来言語のインパクト[編集]

French is noticeably different from most other Romance languages. Some of the changes have been attributed to substrate influence—i.e. to carry-over effects from Gaulish (Celtic) or superstrate—influence from Frankish (Germanic). In practice, it is difficult to say with confidence which sound and grammar changes were due to substrate and superstrate influences, since many of the changes in French have parallels in other Romance languages, or are changes commonly undergone by many languages in the process of development. However, the following are likely candidates.

In phonology:

- The reintroduction of the consonant /h/ at the beginning of a word is due to Frankish influence, and mostly occurs in words borrowed from Germanic. This sound no longer exists in Standard Modern French (—it survives dialectally, particularly in the regions of Normandy, Picardy and Wallonia); however a Germanic h usually disallows liaison: les halles /lɛ.al/, les haies /lɛ.ɛ/, les haltes /lɛ.alt/, whereas a Latin h allows liaison: les herbes /lɛzɛrb/, les hôtels /lɛzotɛl/.

- The reintroduction of /w/ in Northern Norman, Picard, Walloon, Champenois, Bourguignon and Bas-Lorrain[15] is due to Germanic influence. All Romance languages have borrowed Germanic words containing /w/, but all languages south of the isogloss —including the ancestor of Modern French ("Central French")—converted this to /ɡw/ (which remains in some words like e.g. linguistique), which usually developed subsequently into /ɡ/. English borrowed words both from Norman French (1066 – c. 1200 AD) and Standard French (c. 1200–1400 AD), which sometimes results in doublets such as warranty and guarantee.

- The occurrence of an extremely strong stress accent, leading to loss of unstressed vowels and extensive modification of stressed vowels (diphthongisation), is likely to be due to Frankish influence, and possibly to Celtic influence, as both languages had a strong initial stress. (e.g. tela -> TEla -> toile)[16] This feature also no longer exists in Modern French. However, its influence remains in the uniform final word stress in Modern French—due to the strong stress, all vowels following the stress were ultimately lost.

- Nasalisation resulting from compensatory vowel lengthening in stressed syllables due to Germanic stress accent

- The development of front-rounded vowels /y/, /ø/, and /œ/ may be due to Germanic influence, as few Romance languages outside of French have such vowels.

- The lenition of intervocalic consonants (see above) may be due to Celtic influence: A similar change happened in Celtic languages at about the same time, and the demarcation between Romance dialects with and without this change (the La Spezia-Rimini Line) corresponds closely to the limit of Celtic settlement in ancient Rome. The lenition also affected later words borrowed from Germanic (e.g. haïr < hadir < *hatjan; flan < *fladon; (cor)royer < *(ga)rēdan; etc.), suggesting that the tendency persisted for some time after it was introduced.

- The devoicing of word final voiced consonants in Old French is due to Germanic influence (e.g. grant/grande, blont/blonde, bastart/bastarde).

In other areas:

- The development of verb-second syntax in Old French (where the verb must come in second position in a sentence, regardless of whether the subject precedes or follows) is probably due to Germanic influence.

- The first person plural ending -ons (Old French -omes, -umes) is likely derived from the Frankish termination -ōmês, -umês (vs. Latin -āmus, -ēmus, -imus, and -īmus; cf. OHG -ōmēs, -umēs).[17]

- The use of the letter k in Old French, which was replaced by c and qu during the Renaissance, was due to Germanic influence. Typically, k was not used in written Latin and other Romance languages. Similarly, use of w and y was also diminished.

- The impersonal pronoun on "one, you, they" – (from Old French (h)om, a reduced form of homme "man") is a calque of the Germanic impersonal pronoun man "one, you, they", reduced form of mann "man" (cf Old English man "one, you, they", from mann "man"; German man "one, you, they" vs. Mann "man").

- The expanded use of avoir "to have" over the more customary use of tenir "to have, hold" seen in other Romance languages is likely to be due to influence from the Germanic word for "have", which has a similar form (cf. Frankish *habēn, Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa, English have).

- The increased use of auxiliary verbal tenses, especially passé composé, is probably due to Germanic influence. Unknown in Classical Latin, the passé composé begins to appear in Old French in the early 13th century after the Germanic and the Viking invasions. Its construction is identical to the one seen in all other Germanic languages at that time and before: « verb "be" (être) + past participle » when there is movement, indication of state, or change of condition; and « "have" (avoir) + past participle » for all other verbs. Passé composé is not universal to the Romance language family—only Romance languages known to have Germanic superstrata display this type of construction, and in varying degrees (those nearest to Germanic areas show constructions most similar to those seen in Germanic). Italian, Spanish and Catalan are other Romance languages employing this type of compound verbal tense.

- The heightened frequency of si ("so") in Old French correlates to Old High German so and thanne

- The tendency in Old French to use adverbs to complete the meaning of a verb, as in lever sus ("raise up"), monter amont ("mount up"), aler avec ("go along/go with"), traire avant ("draw forward"), etc. is likely to be of Germanic origin

- The lack of a future tense in conditional clauses is likely due to Germanic influence.

- The reintroduction of a vigesimal system of counting by increments of 20 (e.g. soixante-dix "70" lit. "sixty-ten"; quatre-vingts "80" lit. "four-twenties"; quatre-vingt-dix "90" lit. "four-twenty-ten") is due to North Germanic influence, first appearing in Normandy, in northern France. From there, it spread south after the formation of the French Republic, replacing the typical Romance forms still used today in Belgian and Swiss French. The current vigesimal system was introduced by the Vikings and adopted by the Normans who popularised its use (cf Danish tresindstyve, literally 2 times 30, or 60; English four score and seven for 87)[要出典]. Pre-Roman Celtic languages in Gaul also made use of a vigesimal system, but this system largely vanished early in French linguistic history or became severely marginalised in its range. The Nordic vigesimal system may possibly derive ultimately from the Celtic. Old French also had treis vingts, cinq vingts. (cf. Welsh ugain "20", deugain "40", pedwar ugain "80" lit. "four-twenties").

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

出典[編集]

- ^ “Mots francais d'origine gauloise”. Mots d'origine gauloise. 2006年10月22日閲覧。

- ^ Henriette Walter, Gérard Walter, Dictionnaire des mots d’origine étrangère, Paris, 1998

- ^ “The History of the French Language”. Catholic Central French. 2006年8月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2006年3月22日閲覧。

- ^ Walter & Walter 1998.

- ^ Le trésor de la langue française informatisé

- ^ Holmes Jr., Urban T.; A. H. Schutz (1938). A history of the French language. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. pp. 29. ISBN 0819601918 ホームズ・Jr., アーバン・T、アレキサンダー・H・シュッツ 著、松原秀一 訳『フランス語の歴史』大修館書店、1974年、42頁。ASIN B000J94F0I。

- ^ Elisabeth Ridel, Les Vikings et les mots, Editions Errance, 2010

- ^ Baugh, Cable, "A History of the English Language, 104."

- ^ La Vallée d'Aoste : enclave francophone au sud-est du Mont Blanc.

- ^ Henriette Walter, L'aventure des mots français venus d'ailleurs, Robert Laffont, 1998.

- ^ Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780 : programme, myth, reality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990; ISBN 0-521-43961-2) chapter II "The popular protonationalism", pp.80–81 French edition (Gallimard, 1992). According to Hobsbawm, the main source for this subject is Ferdinand Brunot (ed.), Histoire de la langue française, Paris, 1927–1943, 13 volumes, in particular volume IX. He also refers to Michel de Certeau, Dominique Julia, Judith Revel, Une politique de la langue: la Révolution française et les patois: l'enquête de l'abbé Grégoire, Paris, 1975. For the problem of the transformation of a minority official language into a widespread national language during and after the French Revolution, see Renée Balibar, L'Institution du français: essai sur le co-linguisme des Carolingiens à la République, Paris, 1985 (also Le co-linguisme, PUF, Que sais-je?, 1994, but out of print) ("The Institution of the French language: essay on colinguism from the Carolingian to the Republic. Finally, Hobsbawm refers to Renée Balibar and Dominique Laporte, Le Français national: politique et pratique de la langue nationale sous la Révolution, Paris, 1974.

- ^ Anonymous, "Chirac upset by English address," BBC News, 24 March 2006.

- ^ Anonymous, "French fury over English language," BBC News, 8 February 2007.

- ^ Statistics Canada: 2006 Census

- ^ Jacques Allières, La formation du Français, P.U.F.

- ^ Cerquiglini, Bernard. Une langue orpheline, Éd. de Minuit, 2007.

- ^ Pope, From Latin to modern French, with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman, p16.