オステオポンチン

この記事はカテゴライズされていないか、不十分です。 |

| Osteopontin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 識別子 | |||||||||

| 略号 | Osteopontin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00865 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002038 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00689 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

オステオポンチン(Osteopontin, OPN)またの名を骨シアロ蛋白質I(bone/sialoprotein I, BSP-1,BNSP)、Tリンパ球活性化1蛋白質[5](early T-lymphocyte activation, Eta-1)、分泌型リン蛋白質1(secreted phosphoprotein 1, SPP1)、2ar、リケッチア耐性因子[訳語疑問点](Rickettsia resistance, Ric)は[6]、SPP1 遺伝子でコードされるヒト蛋白質である。

解説[編集]

ネズミにおける相同分子はSpp1 。1986年に初めて骨芽細胞で同定されたSIBLING蛋白質(糖蛋白質)である。

接頭辞のオステオ(osteo-)はこの蛋白質が骨で発現していることを示しているが、他の組織でも発現している。接尾辞のポンチン(-pontin)は、ラテン語で橋を意味する“pons”に由来し、オステオポンチンが架橋蛋白質としての役割を担っていることを示す。オステオポンチンは細胞外構造蛋白質であり、従って骨の有機成分である。

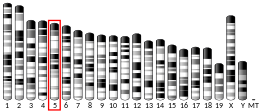

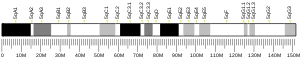

この遺伝子は7つのエクソンを持ち、長さは5千塩基対(5kbp)に及び、ヒトでは4番染色体第22領域(4q1322.1)の長腕に位置している。蛋白質は約300アミノ酸残基からなり、ゴルジ体での翻訳後修飾の際に蛋白質に結合する10個のシアル酸残基を含む約30個の糖鎖が結合している。アミノ酸には酸性のものが多く含まれ、蛋白質の30-36%はアスパラギン酸またはグルタミン酸である。

構造[編集]

オステオポンチンは強い負電荷を帯び、高度にリン酸化された細胞外マトリックス蛋白質であり、本質的に無秩序な蛋白質であって大規模な二次構造を欠いている[7][8]。約300個のアミノ酸(マウスでは297個、ヒトでは314個)からなり、33kDaの新生タンパク質として発現し、機能的に重要な切断部位も含まれる。オステオポンチンは翻訳後修飾を受け、見掛けの分子量は約44kDaに増加する[9]。OPN 遺伝子は7つのエクソンからなり、そのうち6つはコード配列を含む[10][11]。最初の2つのエクソンは5'非翻訳領域(5'UTR)を含む[12]。エクソン2、3、4、5、6、7はそれぞれ17、13、27、14、108、134アミノ酸をコードする[12]。イントロンとエクソンの境界はすべてフェーズ0タイプであるため、選択的エクソンスプライシングによってOPN 遺伝子のリーディングフレームが維持されている。

アイソフォーム[編集]

オステオポンチンの全長(OPN-FL)はトロンビン切断によって修飾され、OPN-Rとして知られる切断型蛋白質上にSVVYGLRという配列が露出する(図1)。このトロンビン切断型OPN(OPN-R)は、α4β1、α9β1、α9β4のインテグリン受容体のエピトープを露出する[14][15]。これらのインテグリン受容体は、肥満細胞[16]、好中球[17]、T細胞など多くの免疫細胞に存在する。単球やマクロファージにも発現している[18]。これらの受容体と結合すると、細胞はいくつかのシグナル伝達経路を用いて、これらの細胞に免疫応答を引き起こす。OPN-RはさらにカルボキシペプチダーゼB(CPB)によってC末端のアルギニンが除去され、OPN-Lとなる。OPN-Lの機能は殆ど不明である。

オステオポンチンの細胞内変種(iOPN)は、遊走、融合、運動性を含む多くの細胞プロセスに関与していると思われる[19][20][21][22]。細胞内OPNは、細胞外アイソフォームの生成に使われるのと同じmRNA種上の選択的翻訳開始部位を用いて生成される[23]。この代替翻訳開始部位はN末端小胞体標的シグナル配列の下流にあるため、OPNの細胞質内翻訳が可能である。

乳癌を含む様々なヒトのがんでは、オステオポンチンのスプライス変種が発現していることが観察されている[24][25]。がんに特異的なスプライス変種は、オステオポンチン-a、オステオポンチン-b、オステオポンチン-cである。オステオポンチン-bはエクソン5を欠き、オステオポンチン-cはエクソン4を欠く[24]。オステオポンチン-cは細胞外マトリックスに結合できないため、ヒト乳癌細胞の足場非依存性表現型を促進することが示唆されている[24]。

組織分布[編集]

オステオポンチンは、心線維芽細胞[26]、前骨芽細胞、骨芽細胞、骨細胞、歯芽細胞、一部の骨髄細胞、肥大した軟骨細胞、樹状細胞、マクロファージ[27]、平滑筋[28]、骨格筋筋芽細胞[29]、内皮細胞、および内耳、脳、腎臓、十二指腸、胎盤の骨外(非骨)細胞など、さまざまな組織型で発現している。オステオポンチンの合成は、カルシトリオール(1,25-ジヒドロキシ-ビタミンD3)により刺激される。

制御[編集]

オステオポンチン遺伝子の発現制御はまだ完全には理解されていない。OPN 遺伝子の発現制御機構は、細胞の種類によって異なる可能性がある。骨におけるOPNの発現は、破骨細胞(骨を吸収する細胞)だけでなく、骨芽細胞や骨細胞(骨を形成する細胞)によっても起こる[30]。OPNの発現にはRunx2(別名Cbfa1)とosterix(Osx)転写因子が必要である[31]。Runx2とOsxはCol1α1、Bsp、Opn のような骨芽細胞特異的遺伝子のプロモーターに結合し、転写を上方制御する[32]。

低カルシウム血症および低リン血症(腎近位尿細管細胞を刺激してカルシトリオール(1α,25-ジヒドロキシビタミンD3)を産生させるような場合)は、OPNの転写、翻訳、分泌を増加させる[33]。これは、OPN 遺伝子プロモーターに高特異性ビタミンD応答配列(VDRE)が存在するためである[34][35][36]。

オステオポンチンの発現はマンソン住血吸虫(Schistosoma mansoni )卵抗原によっても調節される[37]。

マンソン住血吸虫卵抗原は、線維形成促進性分子であるオステオポンチンの発現を直接刺激し、全身のオステオポンチン濃度は疾患の重症度と強く相関することから、罹患バイオマーカーとしての利用が示唆される。慢性マウス住血吸虫症において、プラジカンテル(PZQ)投与が全身オステオポンチン濃度および肝コラーゲン沈着に及ぼす影響を調査した結果、PZQ投与が全身オステオポンチン濃度と肝コラーゲン沈着を有意に減少させることが明らかとなり、オステオポンチンがPZQの有効性および線維症の軽減をモニタリングするための信頼性の高いツールになり得ることが示された[38][37]。

細胞外無機リン酸(ePi)もまた、OPN発現の調節因子として特定されている[39]。

オステオポンチンの発現は、急性炎症の古典的メディエーターである炎症性サイトカイン[40](腫瘍壊死因子α(TNFα)、インターロイキン-1β(IL-1β)など)、アンジオテンシンII、トランスフォーミング増殖因子β(TGFβ)、副甲状腺ホルモン(PTH)[41][42]に細胞が晒された時にも刺激されるが、これらの制御経路の詳細な機序はまだ判っていない。高血糖と低酸素症もオステオポンチンの発現を増加させることが知られている[41][43][44]。

機能[編集]

アポトーシス[編集]

オステオポンチンは多くの状況において重要な抗アポトーシス因子である。オステオポンチンは、有害な刺激に晒された線維芽細胞や内皮細胞だけでなく、マクロファージやT細胞の活性化による細胞死を阻止する[45][46]。オステオポンチンは炎症性大腸炎における非プログラム細胞死を妨げる[47]。

生体鉱物生成作用[編集]

オステオポンチンは分泌型酸性蛋白質(SIBLINGs[注 1])ファミリーに属し、そのメンバーはAspやGluなどの負電荷を帯びたアミノ酸を豊富に含む[48]。オステオポンチンはまた、翻訳後にSer残基をリン酸化してホスホセリンを形成するためのコンセンサス配列部位も多数持っており、更なる負電荷を与える[49]。オステオポンチンの中で高陰性電荷を持つ一連の連続領域は同定され、polyAspモチーフ(ポリアスパラギン酸)およびASARMモチーフ[注 2]と命名されており、後者の配列には複数のリン酸化部位がある[50][51][52][53]。オステオポンチンのこの全体的な負電荷は、その特異的な酸性モチーフ、およびオステオポンチンが本質的に無秩序な蛋白質[54][7]でありオープンでフレキシブルな構造が可能であるという事実とともに、オステオポンチンが様々な生体鉱物中の結晶表面に存在するカルシウム原子に強く結合することを可能にしている[53][55][56]。骨や歯に含まれるリン酸カルシウム[57]、内耳の耳石や鳥類の卵殻に含まれる炭酸カルシウム[58][59]、腎臓結石に含まれるシュウ酸カルシウム[60][61][62]など、さまざまな種類のカルシウム系生体鉱物へのオステオポンチンの結合は、一過性の石灰化前駆体相[訳語疑問点]を安定化させることにより、また結晶表面に直接結合することにより、石灰化阻害剤として作用し、これらすべてが結晶成長を制御する[63][64][65]。

オステオポンチンは多くの酵素の基質蛋白質であり、その酵素の作用がオステオポンチンの石灰化抑制機能を調節している可能性がある。PHEX[注 3]はそのような酵素の一つで、オステオポンチンを広範に分解し、その不活性化遺伝子変異(X連鎖性低リン血症、 XLH)では、オステオポンチンの制御が変化するため、石灰化を抑制するオステオポンチンが分解されず、骨(および歯)の細胞外マトリックスに蓄積し、XLHに特徴的な骨軟化症(骨が軟らかい低石灰化骨、歯が軟らかい歯軟化症)を局所的に引き起こす[66][67][13]。オステオポンチンが関与する局所的で生理的な二重陰性(阻害作用阻害剤)石灰化制御を説明する関係は、石灰化の型板原理[訳語疑問点]と呼ばれており、酵素-基質ペアが石灰化阻害剤(例えば、ピロリン酸阻害を解除する組織非特異的アルカリホスファターゼ(TNAP)、オステオポンチン阻害を解除するPHEX)を分解することにより、細胞外マトリックスに石灰化パターンを刻印する(最も顕著に骨について記述されている)[68][65]。石灰化疾患との関連では、型板原理は特に、低ホスファターゼ症やX連鎖性低ホスファターゼ症で観察される骨軟化症や歯軟化症に関連している。

オステオポンチンは、骨や歯の細胞外マトリックス内の正常な石灰化の制御におけるその役割とともに[69]、尿路結石[60][62]や血管石灰化[70][71]などの病的な異所性石灰化[71][72]の部位でも発現が亢進しており、おそらく少なくとも部分的には、これらの軟部組織における消耗性疾患に関する石灰化を抑制するためであろう[訳語疑問点]。

骨再形成[編集]

オステオポンチンは骨再形成に重要な因子として関与している[73]。具体的には、オステオポンチンは破骨細胞を骨表面に固定し、その石灰結合特性により固定化され、RGDモチーフを破骨細胞のインテグリン結合に利用することで、細胞の接着と移動を可能にする[16]。骨表面のオステオポンチンは薄い有機層、いわゆる境界膜[注 4]に存在する[74]。骨の有機成分は乾燥重量の約20%で、オステオポンチン以外に、I型コラーゲン、オステオカルシン、オステオネクチン、アルカリホスファターゼが含まれる。コラーゲンI型は蛋白質量の90%を占める。骨の無機質部分は水酸燐灰石という鉱物で、Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2である。食事からカルシウムが供給されないと骨はカルシウム不足に陥るため、骨粗鬆症になる可能性がある。

オステオポンチンは、破骨細胞が骨吸収を開始するにあたり、その波状縁を形成するプロセスを開始する役割を果たす。オステオポンチンはRGDインテグリン結合モチーフを持つ。

細胞活性化[編集]

活性化T細胞はIL-12によってTh1型への分化が促進され、IL-12やIFNγなどのサイトカインを産生する。オステオポンチンはTh2サイトカインであるIL-10の産生を抑制し、Th1反応を亢進させる。オステオポンチンは細胞性免疫に影響を及ぼし、Th1サイトカインとしての機能を持つと共に、B細胞の免疫グロブリンの産生と増殖を促進する[8]。オステオポンチンはまた、肥満細胞の脱顆粒を誘導する[75]。IgEを介したアナフィラキシーは、OPNノックアウトマウスでは野生型マウスに比べて有意に減少する。OPN産生腫瘍はOPN欠損腫瘍に比べてマクロファージの活性化を誘導できることから、マクロファージの活性化におけるオステオポンチンの役割は、がんにも関係しているとされる[76]。

走化性[編集]

オステオポンチンはアルコール性肝疾患における好中球の動員において重要な役割を果たしている[17][77]。オステオポンチンは試験管内での好中球の遊走に重要である[78]。加えて、オステオポンチンは関節リウマチのコラーゲン関節炎モデルにおいて、炎症細胞を関節炎関節に動員する[79][80]。2008年に行われた最近のin vitro 研究では、オステオポンチンが肥満細胞の遊走に関与していることが明らかにされた[75]。オステオポンチンをノックアウトした肥満細胞を培養したところ、野生型肥満細胞に比べて走化性が低下していることが観察された。オステオポンチンはマクロファージの走化性因子としても働くことが判明した[81]。アカゲザルでは、オステオポンチンはマクロファージが脳内の集積部位から離れるのを阻止し、しかし走化性を亢進させていることが示された。

免疫系[編集]

オステオポンチンは、白血球が発現するα4β1、α9β1、α9β4などのインテグリン受容体に結合する。これらの受容体は、白血球の細胞接着、遊走、生存について機能することが立証されている。

オステオポンチンは、マクロファージ、好中球、樹状細胞、ミクログリア、T細胞、B細胞など、様々な免疫細胞で発現しており、その動態は様々である。オステオポンチンは様々な形で免疫調節因子として働くことが報告されている[8]。まず、オステオポンチンには走化性があり、炎症部位への細胞の動員を促進する。オステオポンチンは接着蛋白質としても機能し、細胞接着や創傷治癒に関与する。さらに、オステオポンチンは細胞の活性化とサイトカイン産生を仲介し、アポトーシスを制御して細胞の生存を促進する[8]。

臨床的重要性[編集]

オステオポンチンは、遍在的に発現する複数の細胞表面受容体と相互作用することで、創傷治癒、骨代謝、腫瘍形成、炎症、虚血、免疫応答など、多くの生理的・病理学的プロセスに積極的に関与している。血漿(または局所)オステオポンチン濃度の変更は、自己免疫疾患、がん転移、骨(および歯)の石灰化関連疾患、骨粗鬆症、およびある種のストレスの治療に有用であろう[8]。

自己免疫疾患[編集]

オステオポンチンは関節リウマチの病因に関与している。オステオポンチンのトロンビン切断型であるOPN-Rは関節リウマチ罹患関節で上昇する。しかし、関節リウマチにおけるオステオポンチンの役割はまだ不明である。あるグループはOPNノックアウトマウスが関節炎から保護されることを発見したが[82]、他のグループはこの観察を再現できなかった[83]。

オステオポンチンは、自己免疫性肝炎、アレルギー性気道疾患、多発性硬化症など、他の自己免疫疾患にも関与していることが知られている[84]。

アレルギーと喘息[編集]

オステオポンチンは最近、アレルギー性炎症や喘息と関連していると考えられている。オステオポンチンの発現は、喘息患者の肺上皮および上皮下細胞において、健常人と比較して有意に増加しており[85]、またアレルギー性気道炎症を起こしたマウスの肺でも上昇している[85]。オステオポンチンの分泌型(OPN-s)は、アレルゲン感作(OVA/Alum[注 5])時に炎症促進的な役割を果たし、この段階でOPN-sを中和すると、アレルギー性気道炎症が有意に軽快する[85]。対照的に、抗原に晒されている段階でのOpn-sの中和はアレルギー性気道疾患を悪化させる[85]。OPN-sのこれらの作用は、主に一次感作期にはTh2抑制性形質細胞様樹状細胞(DC)の制御によって、二次抗原投与時にはTh2促進性通常型DCの制御によって媒介される[85]。オステオポンチン欠乏はまた、気道リモデリングの慢性抗原曝露モデルを用いて、リモデリングと気管支過感受性(BHR)を抑制することが報告された[86]。さらに最近、オステオポンチンの発現がヒト喘息で上昇し、リモデリングの変化と関連し、その上皮下発現が疾患の重症度と相関することが示された[87]。オステオポンチンはまた、喫煙喘息患者の喀痰上清[88]や、対照となる喫煙者および非喫煙喘息患者の気管支肺胞洗浄液および気管支組織で増加することが報告されている[89]。

大腸炎[編集]

オステオポンチンは炎症性腸疾患(IBD)で発現が上昇する[90]。オステオポンチンの発現は、クローン病(CD)および潰瘍性大腸炎(UC)患者の腸管免疫細胞および非免疫細胞、血漿、ならびに実験的大腸炎マウスの大腸および血漿で非常に上昇している[90][91][92]。血漿中オステオポンチン濃度の増加はCDの炎症の重症度と関連しており、特定のOPN遺伝子(Spp1)ハプロタイプはCD感受性の修飾因子である。オステオポンチンはまた、IBDのマウスモデルであるTNBS・DSS[注 6]誘発大腸炎においても炎症促進作用を示す。オステオポンチンはマウス腸間膜リンパ節(MLN)由来の特定の樹状細胞(DC)サブセットで高度に発現し、大腸炎において炎症促進性が強いことが判明した[93]。樹状細胞は、ヒトのIBDや実験的大腸炎マウスにおける腸炎の発症に重要である。この炎症性MLN樹状細胞サブセットによるオステオポンチン発現は、大腸炎時の病原性作用に極めて重要である[93]。

癌[編集]

オステオポンチンがIL-17産生を促進することが示されており[94]、肺癌、乳癌、結腸直腸癌、胃癌、卵巣癌、甲状腺乳頭癌、悪性黒色腫、胸膜中皮腫などの様々な癌で過剰発現している他、糸球体腎炎および尿細管間質性腎炎の両方に寄与している。また、動脈内のアテローム斑に認められる。従って、血漿オステオポンチン濃度の操作は、自己免疫疾患、癌転移、骨粗鬆症、およびある種のストレスの治療に有用であろうと思われる[8]。

オステオポンチンはPDAC(膵臓腺癌)の病勢進行に関与している[95]。PDACでは3つのスプライス変異が発現し、オステオポンチン-aはほぼ全てのPDACで発現する他、オステオポンチン-bの発現は生存率と相関し、オステオポンチン-cの発現は転移病変と相関する。PDACではオステオポンチンが交互にスプライシングされた形で分泌されるため、腫瘍特異的、病期特異的な標的設定が可能である。PDACにおけるオステオポンチンシグナル伝達の正確なメカニズムは不明であるが、オステオポンチンはCD44およびインテグリンと結合し、腫瘍の進行や補体阻害などのプロセスを引き起こす。オステオポンチンはまた、血管内皮増殖因子(VEGF)とマトリックスメタロプロテアーゼ(MMP)の放出を誘発することによって転移を促進するが、これはオステオポンチンをノックダウンすることによって抑制される。この過程はニコチンによっても刺激され、喫煙者が膵癌リスクを上昇させるメカニズムとして提唱されており、膵癌のマーカーとして研究されている。オステオポンチンは、膵管内乳頭粘液性腫(IPMN)や切除可能な(初期の)PDACと膵炎との鑑別において、CA19-9よりも優れていることが判明している。hu1A12などの抗オステオポンチン抗体は、in vivo 試験で転移を抑制し、抗VEGF抗体ベバシズマブとの混用(併用?)でも転移を抑制した。少なくとも1つの臨床試験では、腫瘍内低酸素状態のマーカーとしてのオステオポンチンの使用が検討されている。しかし、このマーカーは比較的未解明のままである[96]。

オステオポンチンは過剰な瘢痕形成にも関与しており、その影響を抑制するゲルが開発された[97]。

オステオポンチンを阻害する抗オステオポンチンモノクローナル抗体薬AOM1は、非小細胞肺癌(NSCLC)のマウスモデルにおいて、大きな転移性腫瘍の進行を阻止することが期待された[98][99]。

オステオポンチンは転移を促進し、癌のバイオマーカーとして使用される可能性があるが、最新の研究では、腫瘍の発生過程において、この分子が自然免疫細胞集団を保護する機能があることが新たに報告された。特に、最適な免疫機能を持つナチュラルキラー(NK)細胞のプールを維持することは、がん腫瘍形成に対する宿主の防御にとって極めて重要である。米国科学アカデミー紀要に掲載された研究によれば、iOPN[注 7]は機能的なNK細胞の増殖を維持するために不可欠な分子である。iOPNが欠乏すると、正常なNK細胞質を維持できなくなり、サイトカインIL-15による刺激後に細胞死が増加する。オステオポンチン欠乏NK細胞は免疫応答の収縮期をうまく通過できず、その結果、長寿命NK細胞の増加が損なわれ、腫瘍細胞に対する応答に欠陥が生じる[100]。さらに、形質細胞様樹状細胞(pDC)は悪性黒色腫を防止し、この効果はI型IFNによって媒介される[101]。Journal of Cell Biology 誌掲載の研究により、オステオポンチン蛋白質の特異的断片(SLAYGLR)が、pDCを悪性黒色腫の発生から保護するためにより“適合”させ得ることが示された。これは、MyD88遺伝子非依存性で、PI3K/mTOR/IRF3[注 8]経路を介して作動する新規のα4インテグリン/IFN-β軸の活性化によって実現される[102]。

心不全[編集]

オステオポンチンは正常な状態ではほとんど発現しないが、心臓の機能が低下すると急速に蓄積する[103][104]。特に、心筋梗塞後のリモデリングにおいて中心的な役割を果たしており、肥大型心筋症(HCM)や拡張型心筋症(DCM)では劇的に発現が上昇する[104]。一旦増加すると、血管新生、サイトカインの局所産生、筋線維芽細胞の分化、細胞外マトリックスの沈着の増加、心筋細胞の肥大など、心筋の広範な生理的変化を惹起する。これらを総合すると、心臓の構造がリモデリングされ、実質的に心臓の正常な機能が低下し、心不全のリスクが増加する[105][106]。

パーキンソン病[編集]

オステオポンチンは酸化・ニトロソ化ストレス、アポトーシス、ミトコンドリア機能障害、興奮毒性に関与しており、これらはパーキンソン病(PD)の病態にも関与している。PD患者の血清および脳脊髄液中のオステオポンチン濃度を調べたところ、PD患者では体液中のオステオポンチン濃度が上昇していることが示された[107]。

筋疾患および疼痛[編集]

オステオポンチンがデュシェンヌ型筋ジストロフィーのような骨格筋疾患において多くの役割を果たしていることを示唆する証拠が蓄積されつつある。オステオポンチンは、筋ジストロフィーや傷害を受けた筋の炎症環境の構成要素として報告されており[29][108][109][110]、また、老化した筋ジストロフィーマウスの横隔膜筋の瘢痕化を増加させることも示されている[111]。最近の研究で、オステオポンチンがデュシェンヌ型筋ジストロフィー患者の重症度を決定する因子であることが判明した[112]。この研究では、低濃度のオステオポンチン発現を引き起こすことが知られているオステオポンチン遺伝子プロモーターの変異が、デュシェンヌ型筋ジストロフィー患者における歩行や筋力喪失までの年齢の低下と関連していることが明らかにされた。

変形性股関節症[編集]

特発性変形性股関節症患者では、血漿中オステオポンチン濃度の上昇が観察されている。さらに、血漿中オステオポンチン濃度と疾患の重症度との相関も指摘されている[113]。

受精卵の着床[編集]

オステオポンチンは着床時に子宮内膜細胞に発現する。卵巣によるプロゲステロンの産生により、オステオポンチンは着床を補助するために大幅に上方制御される。子宮内膜は脱落膜化を受ける必要があり、この過程では、子宮内膜が着床の準備をするために変化し、胚の付着に繋がる。子宮内膜には、胚が付着するのに最適な環境を作り出すために分化する間質細胞が存在する。オステオポンチンは間質細胞の増殖と分化に不可欠な蛋白質であり、αvβ3受容体に結合して接着を助ける。オステオポンチンは脱落膜化とともに、最終的に初期胚の着床を成功に導く。OPN遺伝子がノックアウトされると、母体-胎児間の接着が不安定になる[114][115]。

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

- ^ Small Integrin Binding LIgand N-Glycosylated proteins;低分子量インテグリン結合リガンド-N結合糖蛋白質

- ^ Acidic Serine- and Aspartate-Rich Motif;酸性のセリンおよびアスパラギン酸に富むモチーフ

- ^ Phosphate-regulating Endopeptidase homolog X-linked;リン酸調節中性エンドペプチダーゼX連鎖性相同体

- ^ 羅: lamina limitans

- ^ 鶏卵アルブミン・水酸化アルミニウム複合体を用いて実験的にTh2細胞性免疫反応を誘導する。

- ^ Trinitrobenzenesulfonic Acid/Dextran Sodium Sulfate;トリニトロベンゼンスルホン酸・デキストラン硫酸ナトリウム

- ^ intracellular variant of Osteopontin

- ^ Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin/interferon regulatory factor-3;ホスファチジルイノシトール3-キナーゼ/哺乳類ラパマイシン標的タンパク質/インターフェロン調節因子-3

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000118785 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029304 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ Osada, Manabu. “初期のTリンパ球活性化1(Eta-1)タンパク質とin vitroでのマウスマクロファージ間の特異的相互作用の定義とin vivoでのマクロファージへの影響 - Bibgraph(ビブグラフ)| PubMedを日本語で論文検索”. Bibgraph(ビブグラフ). 2024年2月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Entrez Gene: SPP1 secreted phosphoprotein 1”. 2024年2月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b Kalmar L, Homola D, Varga G, Tompa P (September 2012). “Structural disorder in proteins brings order to crystal growth in biomineralization”. Bone 51 (3): 528–534. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2012.05.009. PMID 22634174.

- ^ a b c d e f Wang KX, Denhardt DT (2008). “Osteopontin: role in immune regulation and stress responses”. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 19 (5–6): 333–345. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.001. PMID 18952487.

- ^ Rangaswami H, Bulbule A, Kundu GC (February 2006). “Osteopontin: role in cell signaling and cancer progression”. Trends in Cell Biology 16 (2): 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.005. PMID 16406521.

- ^ Young MF, Kerr JM, Termine JD, Wewer UM, Wang MG, McBride OW, Fisher LW (August 1990). “cDNA cloning, mRNA distribution and heterogeneity, chromosomal location, and RFLP analysis of human osteopontin (OPN)”. Genomics 7 (4): 491–502. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(90)90191-V. PMID 1974876.

- ^ Kiefer MC, Bauer DM, Barr PJ (April 1989). “The cDNA and derived amino acid sequence for human osteopontin”. Nucleic Acids Research 17 (8): 3306. doi:10.1093/nar/17.8.3306. PMC 317745. PMID 2726470.

- ^ a b Crosby AH, Edwards SJ, Murray JC, Dixon MJ (May 1995). “Genomic organization of the human osteopontin gene: exclusion of the locus from a causative role in the pathogenesis of dentinogenesis imperfecta type II”. Genomics 27 (1): 155–160. doi:10.1006/geno.1995.1018. PMID 7665163.

- ^ a b Barros NM, Hoac B, Neves RL, Addison WN, Assis DM, Murshed M, Carmona AK, McKee MD (March 2013). “Proteolytic processing of osteopontin by PHEX and accumulation of osteopontin fragments in Hyp mouse bone, the murine model of X-linked hypophosphatemia”. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 28 (3): 688–699. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1766. PMID 22991293.

- ^ Laffón A, García-Vicuña R, Humbría A, Postigo AA, Corbí AL, de Landázuri MO, Sánchez-Madrid F (August 1991). “Upregulated expression and function of VLA-4 fibronectin receptors on human activated T cells in rheumatoid arthritis”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 88 (2): 546–552. doi:10.1172/JCI115338. PMC 295383. PMID 1830891.

- ^ Seiffge D (December 1996). “Protective effects of monoclonal antibody to VLA-4 on leukocyte adhesion and course of disease in adjuvant arthritis in rats”. The Journal of Rheumatology 23 (12): 2086–2091. PMID 8970045.

- ^ a b Reinholt FP, Hultenby K, Oldberg A, Heinegård D (June 1990). “Osteopontin--a possible anchor of osteoclasts to bone”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (12): 4473–4475. Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.4473R. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4473. PMC 54137. PMID 1693772.

- ^ a b Banerjee A, Apte UM, Smith R, Ramaiah SK (March 2006). “Higher neutrophil infiltration mediated by osteopontin is a likely contributing factor to the increased susceptibility of females to alcoholic liver disease”. The Journal of Pathology 208 (4): 473–485. doi:10.1002/path.1917. PMID 16440289.

- ^ Sodek J, Batista Da Silva AP, Zohar R (May 2006). “Osteopontin and mucosal protection”. Journal of Dental Research 85 (5): 404–415. doi:10.1177/154405910608500503. PMID 16632752.[リンク切れ]

- ^ Zohar R, Suzuki N, Suzuki K, Arora P, Glogauer M, McCulloch CA, Sodek J (July 2000). “Intracellular osteopontin is an integral component of the CD44-ERM complex involved in cell migration”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 184 (1): 118–130. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<118::AID-JCP13>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 10825241.

- ^ Suzuki K, Zhu B, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Goldberg HA, McCulloch CA, Sodek J (August 2002). “Colocalization of intracellular osteopontin with CD44 is associated with migration, cell fusion, and resorption in osteoclasts”. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 17 (8): 1486–1497. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.8.1486. PMID 12162503.

- ^ Zhu B, Suzuki K, Goldberg HA, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, McCulloch CA, Sodek J (January 2004). “Osteopontin modulates CD44-dependent chemotaxis of peritoneal macrophages through G-protein-coupled receptors: evidence of a role for an intracellular form of osteopontin”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 198 (1): 155–167. doi:10.1002/jcp.10394. PMID 14584055.

- ^ Junaid A, Moon MC, Harding GE, Zahradka P (February 2007). “Osteopontin localizes to the nucleus of 293 cells and associates with polo-like kinase-1”. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 292 (2): C919–C926. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00477.2006. PMID 17005603.

- ^ Shinohara ML, Kim HJ, Kim JH, Garcia VA, Cantor H (May 2008). “Alternative translation of osteopontin generates intracellular and secreted isoforms that mediate distinct biological activities in dendritic cells”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (20): 7235–7239. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.7235S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802301105. PMC 2438233. PMID 18480255.

- ^ a b c He B, Mirza M, Weber GF (April 2006). “An osteopontin splice variant induces anchorage independence in human breast cancer cells”. Oncogene 25 (15): 2192–2202. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209248. PMID 16288209.

- ^ Mirza M, Shaughnessy E, Hurley JK, Vanpatten KA, Pestano GA, He B, Weber GF (February 2008). “Osteopontin-c is a selective marker of breast cancer”. International Journal of Cancer 122 (4): 889–897. doi:10.1002/ijc.23204. PMID 17960616.

- ^ Ashizawa N, Graf K, Do YS, Nunohiro T, Giachelli CM, Meehan WP, Tuan TL, Hsueh WA (November 1996). “Osteopontin is produced by rat cardiac fibroblasts and mediates A(II)-induced DNA synthesis and collagen gel contraction”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 98 (10): 2218–2227. doi:10.1172/JCI119031. PMC 507670. PMID 8941637.

- ^ Murry CE, Giachelli CM, Schwartz SM, Vracko R (December 1994). “Macrophages express osteopontin during repair of myocardial necrosis”. The American Journal of Pathology 145 (6): 1450–1462. PMC 1887495. PMID 7992848.

- ^ Ikeda T, Shirasawa T, Esaki Y, Yoshiki S, Hirokawa K (December 1993). “Osteopontin mRNA is expressed by smooth muscle-derived foam cells in human atherosclerotic lesions of the aorta”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 92 (6): 2814–2820. doi:10.1172/JCI116901. PMC 288482. PMID 8254036.

- ^ a b Uaesoontrachoon K, Yoo HJ, Tudor EM, Pike RN, Mackie EJ, Pagel CN (April 2008). “Osteopontin and skeletal muscle myoblasts: association with muscle regeneration and regulation of myoblast function in vitro”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 40 (10): 2303–2314. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.020. PMID 18490187.

- ^ Merry K, Dodds R, Littlewood A, Gowen M (April 1993). “Expression of osteopontin mRNA by osteoclasts and osteoblasts in modelling adult human bone”. Journal of Cell Science 104 (4): 1013–1020. doi:10.1242/jcs.104.4.1013. PMID 8314886.

- ^ Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B (January 2002). “The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation”. Cell 108 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00622-5. PMID 11792318.

- ^ Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G (May 1997). “Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation”. Cell 89 (5): 747–754. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80257-3. PMID 9182762.

- ^ Yucha C, Guthrie D (December 2003). “Renal homeostasis of calcium”. Nephrology Nursing Journal 30 (6): 755–764. PMID 14730782.

- ^ Prince CW, Butler WT (September 1987). “1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the biosynthesis of osteopontin, a bone-derived cell attachment protein, in clonal osteoblast-like osteosarcoma cells”. Collagen and Related Research 7 (4): 305–313. doi:10.1016/s0174-173x(87)80036-5. PMID 3478171.

- ^ Oldberg A, Jirskog-Hed B, Axelsson S, Heinegård D (December 1989). “Regulation of bone sialoprotein mRNA by steroid hormones”. The Journal of Cell Biology 109 (6 Pt 1): 3183–3186. doi:10.1083/jcb.109.6.3183. PMC 2115918. PMID 2592421.

- ^ Chang PL, Prince CW (April 1991). “1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates synthesis and secretion of nonphosphorylated osteopontin (secreted phosphoprotein 1) in mouse JB6 epidermal cells”. Cancer Research 51 (8): 2144–2150. PMID 2009532.

- ^ a b Pereira TA, Vaz de Melo Trindade G, Trindade Santos E, Pereira FE, Souza MM (May 2021). “Praziquantel pharmacotherapy reduces systemic osteopontin levels and liver collagen content in murine schistosomiasis mansoni”. International Journal for Parasitology 51 (6): 437–440. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2020.11.002. PMID 33493521.

- ^ “Editorial”. International Journal for Parasitology 26 (8–9): 797–798. (1996-08-09). doi:10.1016/0020-7519(96)00065-3. ISSN 0020-7519.

- ^ Fatherazi S, Matsa-Dunn D, Foster BL, Rutherford RB, Somerman MJ, Presland RB (January 2009). “Phosphate regulates osteopontin gene transcription”. Journal of Dental Research 88 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1177/0022034508328072. PMC 3128439. PMID 19131315.

- ^ Guo H, Cai CQ, Schroeder RA, Kuo PC (January 2001). “Osteopontin is a negative feedback regulator of nitric oxide synthesis in murine macrophages”. Journal of Immunology 166 (2): 1079–1086. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1079. PMID 11145688.

- ^ a b Ricardo SD, Franzoni DF, Roesener CD, Crisman JM, Diamond JR (May 2000). “Angiotensinogen and AT(1) antisense inhibition of osteopontin translation in rat proximal tubular cells”. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 278 (5): F708–F716. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F708. PMID 10807582.

- ^ Noda M, Rodan GA (February 1989). “Transcriptional regulation of osteopontin production in rat osteoblast-like cells by parathyroid hormone”. The Journal of Cell Biology 108 (2): 713–718. doi:10.1083/jcb.108.2.713. PMC 2115413. PMID 2465299.

- ^ Hullinger TG, Pan Q, Viswanathan HL, Somerman MJ (January 2001). “TGFbeta and BMP-2 activation of the OPN promoter: roles of smad- and hox-binding elements”. Experimental Cell Research 262 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1006/excr.2000.5074. PMID 11120606.

- ^ Sodhi CP, Phadke SA, Batlle D, Sahai A (April 2001). “Hypoxia and high glucose cause exaggerated mesangial cell growth and collagen synthesis: role of osteopontin”. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 280 (4): F667–F674. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F667. PMID 11249858.

- ^ Denhardt DT, Noda M, O'Regan AW, Pavlin D, Berman JS (May 2001). “Osteopontin as a means to cope with environmental insults: regulation of inflammation, tissue remodeling, and cell survival”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 107 (9): 1055–1061. doi:10.1172/JCI12980. PMC 209291. PMID 11342566.

- ^ Standal T, Borset M, Sundan A (September 2004). “Role of osteopontin in adhesion, migration, cell survival and bone remodeling”. Experimental Oncology 26 (3): 179–184. PMID 15494684.

- ^ Da Silva AP, Pollett A, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Sodek J, Zohar R (September 2006). “Exacerbated tissue destruction in DSS-induced acute colitis of OPN-null mice is associated with downregulation of TNF-alpha expression and non-programmed cell death”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 208 (3): 629–639. doi:10.1002/jcp.20701. PMID 16741956.

- ^ Fisher LW, Fedarko NS (2003). “Six genes expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the SIBLING family of proteins”. Connective Tissue Research 44 (Suppl 1): 33–40. doi:10.1080/03008200390152061. PMID 12952171.

- ^ Christensen B, Nielsen MS, Haselmann KF, Petersen TE, Sørensen ES (August 2005). “Post-translationally modified residues of native human osteopontin are located in clusters: identification of 36 phosphorylation and five O-glycosylation sites and their biological implications”. The Biochemical Journal 390 (Pt 1): 285–292. doi:10.1042/BJ20050341. PMC 1184582. PMID 15869464.

- ^ David V, Martin A, Hedge AM, Drezner MK, Rowe PS (March 2011). “ASARM peptides: PHEX-dependent and -independent regulation of serum phosphate”. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 300 (3): F783–F791. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00304.2010. PMC 3064126. PMID 21177780.

- ^ Martin A, David V, Laurence JS, Schwarz PM, Lafer EM, Hedge AM, Rowe PS (April 2008). “Degradation of MEPE, DMP1, and release of SIBLING ASARM-peptides (minhibins): ASARM-peptide(s) are directly responsible for defective mineralization in HYP”. Endocrinology 149 (4): 1757–1772. doi:10.1210/en.2007-1205. PMC 2276704. PMID 18162525.

- ^ Addison WN, Nakano Y, Loisel T, Crine P, McKee MD (October 2008). “MEPE-ASARM peptides control extracellular matrix mineralization by binding to hydroxyapatite: an inhibition regulated by PHEX cleavage of ASARM”. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 23 (10): 1638–1649. doi:10.1359/jbmr.080601. PMID 18597632.

- ^ a b Addison WN, Masica DL, Gray JJ, McKee MD (April 2010). “Phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of mineralization by osteopontin ASARM peptides is regulated by PHEX cleavage”. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 25 (4): 695–705. doi:10.1359/jbmr.090832. PMID 19775205.

- ^ Kurzbach D, Platzer G, Schwarz TC, Henen MA, Konrat R, Hinderberger D (August 2013). “Cooperative unfolding of compact conformations of the intrinsically disordered protein osteopontin”. Biochemistry 52 (31): 5167–5175. doi:10.1021/bi400502c. PMC 3737600. PMID 23848319.

- ^ Azzopardi PV, O'Young J, Lajoie G, Karttunen M, Goldberg HA, Hunter GK (February 2010). “Roles of electrostatics and conformation in protein-crystal interactions”. PLOS ONE 5 (2): e9330. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...5.9330A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009330. PMC 2824833. PMID 20174473.

- ^ Hunter GK, O'Young J, Grohe B, Karttunen M, Goldberg HA (December 2010). “The flexible polyelectrolyte hypothesis of protein-biomineral interaction”. Langmuir 26 (24): 18639–18646. doi:10.1021/la100401r. PMID 20527831.

- ^ McKee MD, Nanci A (May 1995). “Postembedding colloidal-gold immunocytochemistry of noncollagenous extracellular matrix proteins in mineralized tissues”. Microscopy Research and Technique 31 (1): 44–62. doi:10.1002/jemt.1070310105. PMID 7626799.

- ^ Takemura T, Sakagami M, Nakase T, Kubo T, Kitamura Y, Nomura S (September 1994). “Localization of osteopontin in the otoconial organs of adult rats”. Hearing Research 79 (1–2): 99–104. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(94)90131-7. PMID 7806488.

- ^ Hincke MT, Nys Y, Gautron J, Mann K, Rodriguez-Navarro AB, McKee MD (January 2012). “The eggshell: structure, composition and mineralization”. Frontiers in Bioscience 17 (4): 1266–1280. doi:10.2741/3985. PMID 22201802.

- ^ a b McKee MD, Nanci A, Khan SR (December 1995). “Ultrastructural immunodetection of osteopontin and osteocalcin as major matrix components of renal calculi”. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 10 (12): 1913–1929. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650101211. PMID 8619372.

- ^ O'Young J, Chirico S, Al Tarhuni N, Grohe B, Karttunen M, Goldberg HA, Hunter GK (2009). “Phosphorylation of osteopontin peptides mediates adsorption to and incorporation into calcium oxalate crystals”. Cells Tissues Organs 189 (1–4): 51–55. doi:10.1159/000151724. PMID 18728346.

- ^ a b Chien YC, Masica DL, Gray JJ, Nguyen S, Vali H, McKee MD (August 2009). “Modulation of calcium oxalate dihydrate growth by selective crystal-face binding of phosphorylated osteopontin and polyaspartate peptide showing occlusion by sectoral (compositional) zoning”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (35): 23491–23501. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.021899. PMC 2749123. PMID 19581305.

- ^ Sodek J, Ganss B, McKee MD (2000). “Osteopontin”. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine 11 (3): 279–303. doi:10.1177/10454411000110030101. PMID 11021631.

- ^ Reznikov N, Hoac B, Buss DJ, Addison WN, Barros NM, McKee MD (September 2020). “Biological stenciling of mineralization in the skeleton: Local enzymatic removal of inhibitors in the extracellular matrix”. Bone 138: 115447. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2020.115447. PMID 32454257.

- ^ a b McKee MD, Buss DJ, Reznikov N (March 2022). “Mineral tessellation in bone and the stenciling principle for extracellular matrix mineralization”. Journal of Structural Biology 214 (1): 107823. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2021.107823. PMID 34915130.

- ^ McKee MD, Hoac B, Addison WN, Barros NM, Millán JL, Chaussain C (October 2013). “Extracellular matrix mineralization in periodontal tissues: Noncollagenous matrix proteins, enzymes, and relationship to hypophosphatasia and X-linked hypophosphatemia”. Periodontology 2000 63 (1): 102–122. doi:10.1111/prd.12029. PMC 3766584. PMID 23931057.

- ^ Boukpessi T, Hoac B, Coyac BR, Leger T, Garcia C, Wicart P, Whyte MP, Glorieux FH, Linglart A, Chaussain C, McKee MD (February 2017). “Osteopontin and the dento-osseous pathobiology of X-linked hypophosphatemia”. Bone 95: 151–161. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2016.11.019. PMID 27884786.

- ^ Reznikov N, Hoac B, Buss DJ, Addison WN, Barros NM, McKee MD (September 2020). “Biological stenciling of mineralization in the skeleton: Local enzymatic removal of inhibitors in the extracellular matrix”. Bone 138: 115447. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2020.115447. PMID 32454257.

- ^ McKee MD, Addison WN, Kaartinen MT (2005). “Hierarchies of extracellular matrix and mineral organization in bone of the craniofacial complex and skeleton”. Cells Tissues Organs 181 (3–4): 176–188. doi:10.1159/000091379. PMID 16612083.

- ^ Kaartinen MT, Murshed M, Karsenty G, McKee MD (April 2007). “Osteopontin upregulation and polymerization by transglutaminase 2 in calcified arteries of Matrix Gla protein-deficient mice”. The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry 55 (4): 375–386. doi:10.1369/jhc.6A7087.2006. PMID 17189522.

- ^ a b Steitz SA, Speer MY, McKee MD, Liaw L, Almeida M, Yang H, Giachelli CM (December 2002). “Osteopontin inhibits mineral deposition and promotes regression of ectopic calcification”. The American Journal of Pathology 161 (6): 2035–2046. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64482-3. PMC 1850905. PMID 12466120.

- ^ Giachelli CM (March 1999). “Ectopic calcification: gathering hard facts about soft tissue mineralization”. The American Journal of Pathology 154 (3): 671–675. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65313-8. PMC 1866412. PMID 10079244.

- ^ Choi ST, Kim JH, Kang EJ, Lee SW, Park MC, Park YB, Lee SK (December 2008). “Osteopontin might be involved in bone remodelling rather than in inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis”. Rheumatology 47 (12): 1775–1779. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken385. PMID 18854347.

- ^ McKee MD, Nanci A (1996). “Osteopontin: an interfacial extracellular matrix protein in mineralized tissues”. Connective Tissue Research 35 (1–4): 197–205. doi:10.3109/03008209609029192. PMID 9084658.

- ^ a b Nagasaka A, Matsue H, Matsushima H, Aoki R, Nakamura Y, Kambe N, Kon S, Uede T, Shimada S (February 2008). “Osteopontin is produced by mast cells and affects IgE-mediated degranulation and migration of mast cells”. European Journal of Immunology 38 (2): 489–499. doi:10.1002/eji.200737057. PMID 18200503.

- ^ Crawford HC, Matrisian LM, Liaw L (November 1998). “Distinct roles of osteopontin in host defense activity and tumor survival during squamous cell carcinoma progression in vivo”. Cancer Research 58 (22): 5206–5215. PMID 9823334.

- ^ Apte UM, Banerjee A, McRee R, Wellberg E, Ramaiah SK (August 2005). “Role of osteopontin in hepatic neutrophil infiltration during alcoholic steatohepatitis”. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 207 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.018. PMID 15885730.

- ^ Koh A, da Silva AP, Bansal AK, Bansal M, Sun C, Lee H, Glogauer M, Sodek J, Zohar R (December 2007). “Role of osteopontin in neutrophil function”. Immunology 122 (4): 466–475. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02682.x. PMC 2266047. PMID 17680800.

- ^ Ohshima S, Kobayashi H, Yamaguchi N, Nishioka K, Umeshita-Sasai M, Mima T, Nomura S, Kon S, Inobe M, Uede T, Saeki Y (April 2002). “Expression of osteopontin at sites of bone erosion in a murine experimental arthritis model of collagen-induced arthritis: possible involvement of osteopontin in bone destruction in arthritis”. Arthritis and Rheumatism 46 (4): 1094–1101. doi:10.1002/art.10143. PMID 11953989.

- ^ Sakata M, Tsuruha JI, Masuko-Hongo K, Nakamura H, Matsui T, Sudo A, Nishioka K, Kato T (July 2001). “Autoantibodies to osteopontin in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis”. The Journal of Rheumatology 28 (7): 1492–1495. PMID 11469452.

- ^ Burdo TH, Wood MR, Fox HS (June 2007). “Osteopontin prevents monocyte recirculation and apoptosis”. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 81 (6): 1504–1511. doi:10.1189/jlb.1106711. PMC 2490714. PMID 17369493.

- ^ Yumoto K, Ishijima M, Rittling SR, Tsuji K, Tsuchiya Y, Kon S, Nifuji A, Uede T, Denhardt DT, Noda M (April 2002). “Osteopontin deficiency protects joints against destruction in anti-type II collagen antibody-induced arthritis in mice”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (7): 4556–4561. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.4556Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.052523599. PMC 123686. PMID 11930008.

- ^ Jacobs JP, Pettit AR, Shinohara ML, Jansson M, Cantor H, Gravallese EM, Mathis D, Benoist C (August 2004). “Lack of requirement of osteopontin for inflammation, bone erosion, and cartilage damage in the K/BxN model of autoantibody-mediated arthritis”. Arthritis and Rheumatism 50 (8): 2685–2694. doi:10.1002/art.20381. PMID 15334485.

- ^ Chabas D, Baranzini SE, Mitchell D, Bernard CC, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Sobel RA, Lock C, Karpuj M, Pedotti R, Heller R, Oksenberg JR, Steinman L (November 2001). “The influence of the proinflammatory cytokine, osteopontin, on autoimmune demyelinating disease”. Science 294 (5547): 1731–1735. Bibcode: 2001Sci...294.1731C. doi:10.1126/science.1062960. PMID 11721059.

- ^ a b c d e Xanthou G, Alissafi T, Semitekolou M, Simoes DC, Economidou E, Gaga M, Lambrecht BN, Lloyd CM, Panoutsakopoulou V (May 2007). “Osteopontin has a crucial role in allergic airway disease through regulation of dendritic cell subsets”. Nature Medicine 13 (5): 570–578. doi:10.1038/nm1580. PMC 3384679. PMID 17435770.

- ^ Simoes DC, Xanthou G, Petrochilou K, Panoutsakopoulou V, Roussos C, Gratziou C (May 2009). “Osteopontin deficiency protects against airway remodeling and hyperresponsiveness in chronic asthma”. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 179 (10): 894–902. doi:10.1164/rccm.200807-1081OC. PMID 19234104.

- ^ Samitas K, Zervas E, Vittorakis S, Semitekolou M, Alissafi T, Bossios A, Gogos H, Economidou E, Lötvall J, Xanthou G, Panoutsakopoulou V, Gaga M (February 2011). “Osteopontin expression and relation to disease severity in human asthma”. The European Respiratory Journal 37 (2): 331–341. doi:10.1183/09031936.00017810. PMID 20562127.

- ^ Hillas G, Loukides S, Kostikas K, Simoes D, Petta V, Konstantellou E, Emmanouil P, Papiris S, Koulouris N, Bakakos P (January 2013). “Increased levels of osteopontin in sputum supernatant of smoking asthmatics”. Cytokine 61 (1): 251–255. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2012.10.002. PMID 23098767.

- ^ Samitas K, Zervas E, Xanthou G, Panoutsakopoulou V, Gaga M (March 2013). “Osteopontin is increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and bronchial tissue of smoking asthmatics”. Cytokine 61 (3): 713–715. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2012.12.028. PMID 23384656.

- ^ a b Gassler N, Autschbach F, Gauer S, Bohn J, Sido B, Otto HF, Geiger H, Obermüller N (November 2002). “Expression of osteopontin (Eta-1) in Crohn disease of the terminal ileum”. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 37 (11): 1286–1295. doi:10.1080/003655202761020560. PMID 12465727.

- ^ Sato T, Nakai T, Tamura N, Okamoto S, Matsuoka K, Sakuraba A, Fukushima T, Uede T, Hibi T (September 2005). “Osteopontin/Eta-1 upregulated in Crohn's disease regulates the Th1 immune response”. Gut 54 (9): 1254–1262. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.048298. PMC 1774642. PMID 16099792.

- ^ Mishima R, Takeshima F, Sawai T, Ohba K, Ohnita K, Isomoto H, Omagari K, Mizuta Y, Ozono Y, Kohno S (February 2007). “High plasma osteopontin levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease”. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 41 (2): 167–172. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802d6268. PMID 17245215.

- ^ a b Kourepini E, Aggelakopoulou M, Alissafi T, Paschalidis N, Simoes DC, Panoutsakopoulou V (March 2014). “Osteopontin expression by CD103- dendritic cells drives intestinal inflammation”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (9): E856–E865. Bibcode: 2014PNAS..111E.856K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316447111. PMC 3948306. PMID 24550510.

- ^ Steinman L (February 2007). “A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage”. Nature Medicine 13 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1038/nm1551. PMID 17290272.

- ^ Clay R, Siddiqi SA (January 2019). “Recent advances in molecular diagnostics and therapeutic targets for pancreatic cancer” (英語). Theranostic Approach for Pancreatic Cancer: 325–367. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819457-7.00016-5. ISBN 9780128194577.

- ^ Clay R, Siddiqi SA (2019-01-01). “Recent advances in molecular diagnostics and therapeutic targets for pancreatic cancer” (英語). Theranostic Approach for Pancreatic Cancer: 325–367. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819457-7.00016-5. ISBN 9780128194577.

- ^ Mori R, Shaw TJ, Martin P (January 2008). “Molecular mechanisms linking wound inflammation and fibrosis: knockdown of osteopontin leads to rapid repair and reduced scarring”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 205 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1084/jem.20071412. PMC 2234383. PMID 18180311.

- “Gel 'to speed up wound healing'”. BBC News. (2008年1月22日)

- ^ Shojaei F, Scott N, Kang X, Lappin PB, Fitzgerald AA, Karlicek S, Simmons BH, Wu A, Lee JH, Bergqvist S, Kraynov E (March 2012). “Osteopontin induces growth of metastatic tumors in a preclinical model of non-small lung cancer”. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 31 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-31-26. PMC 3325875. PMID 22444159.

- ^ Farrokhi V, Chabot JR, Neubert H, Yang Z (May 2018). “Assessing the Feasibility of Neutralizing Osteopontin with Various Therapeutic Antibody Modalities”. Scientific Reports 8 (1): 7781. Bibcode: 2018NatSR...8.7781F. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-26187-w. PMC 5958109. PMID 29773891.

- ^ Leavenworth JW, Verbinnen B, Wang Q, Shen E, Cantor H. Intracellular osteopontin regulates homeostasis and function of natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Jan 13;112(2):494-9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423011112. Epub 2014 Dec 30. PMID 25550515; PMC 4299239.

- ^ Drobits B, Holcmann M, Amberg N, Swiecki M, Grundtner R, Hammer M, Colonna M, Sibilia M. Imiquimod clears tumors in mice independent of adaptive immunity by converting pDCs into tumor-killing effector cells. J Clin Invest. 2012 Feb;122(2):575-85. doi:10.1172/JCI61034. Epub 2012 Jan 17. PMID 22251703; PMC 3266798.

- ^ Davina Camargo Madeira Simoes, Nikolaos Paschalidis, Evangelia Kourepini, Vily Panoutsakopoulou; An integrin axis induces IFN-β production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Cell Biol 5 September 2022; 221 (9): e202102055. doi:10.1083/jcb.202102055.

- ^ Singh M, Dalal S, Singh K (November 2014). “Osteopontin: At the cross-roads of myocyte survival and myocardial function”. Life Sciences 118 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2014.09.014. PMC 4254317. PMID 25265596.

- ^ a b Singh M, Foster CR, Dalal S, Singh K (March 2010). “Osteopontin: role in extracellular matrix deposition and myocardial remodeling post-MI”. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 48 (3): 538–543. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.015. PMC 2823840. PMID 19573532.

- ^ Shirakawa K, Sano M (July 2021). “Osteopontin in Cardiovascular Diseases”. Biomolecules 11 (7): 1047. doi:10.3390/biom11071047. PMC 8301767. PMID 34356671.

- ^ Graf K, Do YS, Ashizawa N, Meehan WP, Giachelli CM, Marboe CC, Fleck E, Hsueh WA (November 1997). “Myocardial osteopontin expression is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy”. Circulation 96 (9): 3063–3071. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.9.3063. PMID 9386176.

- ^ Maetzler W, Berg D, Schalamberidze N, Melms A, Schott K, Mueller JC, Liaw L, Gasser T, Nitsch C (March 2007). “Osteopontin is elevated in Parkinson's disease and its absence leads to reduced neurodegeneration in the MPTP model”. Neurobiology of Disease 25 (3): 473–482. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.020. PMID 17188882.

- ^ Porter JD, Khanna S, Kaminski HJ, Rao JS, Merriam AP, Richmonds CR, Leahy P, Li J, Guo W, Andrade FH (February 2002). “A chronic inflammatory response dominates the skeletal muscle molecular signature in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice”. Human Molecular Genetics 11 (3): 263–272. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.3.263. PMID 11823445.

- ^ Haslett JN, Sanoudou D, Kho AT, Bennett RR, Greenberg SA, Kohane IS, Beggs AH, Kunkel LM (November 2002). “Gene expression comparison of biopsies from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and normal skeletal muscle”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (23): 15000–15005. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...9915000H. doi:10.1073/pnas.192571199. PMC 137534. PMID 12415109.

- ^ Hirata A, Masuda S, Tamura T, Kai K, Ojima K, Fukase A, Motoyoshi K, Kamakura K, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S (July 2003). “Expression profiling of cytokines and related genes in regenerating skeletal muscle after cardiotoxin injection: a role for osteopontin”. The American Journal of Pathology 163 (1): 203–215. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63644-9. PMC 1868192. PMID 12819025.

- ^ Vetrone SA, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Kudryashova E, Kramerova I, Hoffman EP, Liu SD, Miceli MC, Spencer MJ (June 2009). “Osteopontin promotes fibrosis in dystrophic mouse muscle by modulating immune cell subsets and intramuscular TGF-beta”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 119 (6): 1583–1594. doi:10.1172/JCI37662. PMC 2689112. PMID 19451692.

- ^ Pegoraro E, Hoffman EP, Piva L, Gavassini BF, Cagnin S, Ermani M, Bello L, Soraru G, Pacchioni B, Bonifati MD, Lanfranchi G, Angelini C, Kesari A, Lee I, Gordish-Dressman H, Devaney JM, McDonald CM (January 2011). “SPP1 genotype is a determinant of disease severity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy”. Neurology 76 (3): 219–226. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318207afeb. PMC 3034396. PMID 21178099.

- ^ El Deeb S, Abdelnaby R, Khachab A, Bläsius K, Tingart M, Rath B (July 2016). “Osteopontin as a biochemical marker and severity indicator for idiopathic hip osteoarthritis”. Hip International 26 (4): 397–403. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000361. PMID 27229171.

- ^ Kang YJ, Forbes K, Carver J, Aplin JD (April 2014). “The role of the osteopontin-integrin αvβ3 interaction at implantation: functional analysis using three different in vitro models”. Human Reproduction 29 (4): 739–749. doi:10.1093/humrep/det433. PMID 24442579.

- ^ Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW, Spencer TE (November 2003). “Osteopontin: roles in implantation and placentation”. Biology of Reproduction 69 (5): 1458–1471. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.103.020651. PMID 12890718.

関連資料[編集]

- Fujisawa R (March 2002). “[Recent advances in research on bone matrix proteins]”. Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 60 60 (Suppl 3): 72–78. PMID 11979972.

- Denhardt DT, Mistretta D, Chambers AF, Krishna S, Porter JF, Raghuram S, Rittling SR (2003). “Transcriptional regulation of osteopontin and the metastatic phenotype: evidence for a Ras-activated enhancer in the human OPN promoter”. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis 20 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1023/A:1022550721404. PMID 12650610.

- Yeatman TJ, Chambers AF (2003). “Osteopontin and colon cancer progression”. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis 20 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1023/A:1022502805474. PMID 12650611.

- O'Regan A (December 2003). “The role of osteopontin in lung disease”. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 14 (6): 479–488. doi:10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00055-8. PMID 14563350.

- Wai PY, Kuo PC (October 2004). “The role of Osteopontin in tumor metastasis”. The Journal of Surgical Research 121 (2): 228–241. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2004.03.028. PMID 15501463.

- Konno S, Hizawa N, Nishimura M, Huang SK (December 2006). “Osteopontin: a potential biomarker for successful bee venom immunotherapy and a potential molecule for inhibiting IgE-mediated allergic responses”. Allergology International 55 (4): 355–359. doi:10.2332/allergolint.55.355. PMID 17130676.

- Rodrigues LR, Teixeira JA, Schmitt FL, Paulsson M, Lindmark-Mänsson H (June 2007). “The role of osteopontin in tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancer”. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 16 (6): 1087–1097. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1008. hdl:1822/7274. PMID 17548669.

- Ramaiah SK, Rittling S (August 2007). “Role of osteopontin in regulating hepatic inflammatory responses and toxic liver injury”. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology 3 (4): 519–526. doi:10.1517/17425225.3.4.519. PMID 17696803.

外部リンク[編集]

- Osteopontin - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス(英語)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P10451 (Osteopontin) at the PDBe-KB.

- オステオポンチン | 雪印ビーンスターク