ヘンリー・オサワ・タナー

ヘンリー・オサワ・タナー | |

|---|---|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner | |

タナーの肖像写真(1907年、フレデリック・グーテクンスト撮影) | |

| 生誕 |

1859年6月21日 |

| 死没 |

1937年5月25日(77歳没) |

| 教育 | |

| 著名な実績 | 絵画、素描 |

| 代表作 |

|

| 運動・動向 | |

| 配偶者 |

Jessie Macauley Olssen (結婚 1899年、死別 1925年) |

| 子供 | 1人 |

| 受賞 |

|

| 選出 |

|

| 後援者 | |

ヘンリー・オサワ・タナー(Henry Ossawa Tanner、1859年6月21日 - 1937年5月25日)は、アメリカ合衆国出身の画家である。キャリアの大半をフランスで過ごした。国際的な評価を得た初のアフリカ系アメリカ人画家である[1]。

1891年にパリに渡ってアカデミー・ジュリアンで学び、フランスの画壇で高い評価を得た。1923年にレジオンドヌール勲章シュヴァリエを受章した[2][3]。

生涯

[編集]若年期

[編集]タナーはペンシルベニア州ピッツバーグで1859年6月21日に生まれた[4]。

父ベンジャミン・タッカー・タナー (1835–1923)は、アメリカ合衆国初の黒人による独立した宗派であるアフリカ・メソジスト監督教会の監督(聖職者)である。ベンジャミンは、アフリカ系アメリカ人のための大学であるアヴェリー大学とピッツバーグ神学校で学び、文学の道へ進んだ[5]。また、奴隷制度廃止運動を支持する政治活動家でもあった。タナーの「オサワ」というミドルネームは、血を流すカンザスの闘争において、奴隷制度反対派と擁護派が戦った1856年のオサワトミーの戦いに因んでつけられたものである[6]。

母サラ・エリザベス・タナーは、バージニア州の奴隷の子として生まれたものと考えられている[7][8]。後にサラは自由黒人となったが、その経緯については2つの異なる話が伝わっている。1つは、彼女の親が家族を牛車に乗せて「自由州」であるペンシルベニア州へ移住させたというものである[7]。もう1つは、サラ個人が、黒人奴隷の逃亡を支援する地下組織である「地下鉄道」の手助けにより北部へ逃亡したというものである[8]。その後、ベンジャミンと出会い、結婚した[7]。

タナー家には少なくとも5人の子供がおり[4]、そのうちの2人、ベンジャミンとホレスは幼少期に死亡した[9]。妹のハレは、アラバマ州の女性で初めて医師免許を取得した[10]。

タナーが10代の時、一家はピッツバーグからフィラデルフィアに転居した[11]。そこで父ベンジャミンは、元奴隷の奴隷制度廃止運動家であるフレデリック・ダグラスと知り合いになった[12]。また、アフリカ系アメリカ人アーティストのロバート・ダグラス・ジュニアが近所に住んでおり、タナーは後に「家の前を通りかかり、いつも窓に飾られた彼の絵を眺めていた」と書いている[13]。タナーが13歳頃のとき、父とともに歩いていたフェアモント公園で風景画家が絵を描いているのを見て、タナーは画家になることを志した[9]。

教育

[編集]

ほとんどの白人アーティストがアフリカ系アメリカ人を弟子に取ることを拒んだ中、フィラデルフィアのペンシルベニア美術アカデミーはタナーを受け入れ、1879年に入学した。タナーは唯一の黒人学生だった[12]。

タナーがこの学校を選んだのは、当時のこの学校が、石膏模型よりも生身のモデルを使った美術研究に重点を置くようになっていたからだった。教授のトマス・エイキンズは、アメリカの芸術教育における新しいアプローチを推進した。例えば、生身のモデルを使った実習を増やす、男女ともに学生に対して解剖学を教える、解剖学の授業のために死体を解剖するなどである。エイキンズの芸術教育に対する進歩的なアプローチは、タナーに大きな影響を与えた。エイキンズはタナーのことを気に入っており、タナーが学校を去ってから20年後に、エイキンズはタナーの肖像画を描いている[14]。

タナーがこの学校で知り合った芸術家たちとは、生涯に渡り交流を続けた。後にアッシュカン・スクール運動を起こすロバート・ヘンライとは特に親交が深かった。タナーはこの学校で、解剖学に関する深い知識と、人体の重量と構造に関する知識をカンバスに表現する技術を身に着けた[15]。

タナーは、1881年11月に病気を患ったことで、退学せざるを得なくなった。タナーは翌年の夏まで、アディロンダック山地で療養生活を送った[16]。

タナーの師には、トマス・エイキンズ(アメリカ写実主義、写真)、トーマス・ホーヴェンデン(アメリカ写実主義)、ジャン=ジョセフ・バンジャマン=コンスタン(オリエンタリズム、フランスアカデミック美術)、ジャン=ポール・ローランス(歴史画、フランスアカデミック美術)などがいた[17][18]。

人種差別の問題

[編集]タナーはアーティストとしての自信を深め、フィラデルフィアで自分の作品を売り始めたが、黒人に対する人種差別と直面した[19]。タナーは自伝の中で、自身が遭遇した人種差別について次のように述べている。

私は極度に臆病で、自分がそこにいる権利が十分にあるにもかかわらず、自分が歓迎されていないと思い知らされ、数か月たっても、時には数週間にわたって苦痛を感じることがあった。これらの不快な出来事が頭に浮かぶたびに、私は落ち込み、それに自分が耐えてきたことを考えると、その出来事そのものと同じくらいに、それによりまた新たに苦しめられた[20]。

ヨーロッパへの渡航費用を稼ぐために、タナーは1880年代後半にアトランタで写真スタジオを経営したが、これは失敗に終わった。

この時期、タナーはクラーク・カレッジ(現クラーク・アトランタ大学)の理事でメソジスト監督教会の監督のジョセフ・クレイン・ハーツゼルと出会った。タナーと親しくなったハーツゼル夫妻は、タナーのパトロンとなり、自身の大学の教員として推薦した[21]。タナーは短期間、クラーク・カレッジでデッサンを教えた[22]。

渡仏

[編集]1891年1月4日、タナーは、リバプール、パリを経由してローマへ向かう「シティ・オブ・チェスター」号に乗り込んだ[23]。途中のパリを気に入ったタナーはそこで下船し、アカデミー・ジュリアンで絵画の勉強を始めた[24]。フランスの画壇では、人種はほとんど問題にされなかった。タナーはサロン・ド・パリに出展して、自分の作品が認められることを目標とした[24]。

『バンジョーのレッスン』

[編集]

1893年に帰国したとき、タナーはシカゴで開催された「世界アフリカ会議」で「芸術におけるアメリカ黒人」と題する論文を発表した[4]。また、アパラチアに住む黒人たちを描いた一連の絵画シリーズを発表し、その中で、タナーの代表作である『バンジョーのレッスン』を描いた[25]。この絵画には、年老いた黒人男性が、その孫と思われる少年にバンジョーの弾き方を教える様子が描かれている[26][27]。19世紀後半のアメリカの芸術作品には、バンジョーを演奏する黒人が数多く登場する[28][27]。

パリでの生活

[編集]時折短期間の帰国をしたのを除いて、タナーは生涯の大半をパリで過ごした。すぐにパリでの生活に慣れ、ニューヨーク出身の画商アサートン・カーティスと知り合った[29][30]。カーティスの勧めで、1902年の6か月間、ニューヨーク州マウント・キスコの芸術家コミュニティに参加した[31]。

パリでタナーは、ジャン=ジョセフ・バンジャマン=コンスタン、ジャン=ポール・ローランスなどの著名な画家たちの指導を受け[20]、フランス画壇で名声を確立し始めた。タナーはノルマンディーのエタプル芸術家村に定住し、そこで出会った芸術家たちから芸術へのアプローチに対する影響を受けた。また、ルーヴル美術館でギュスターヴ・クールベ、ジャン・シメオン・シャルダン、ルイ・ル・ナンの作品と出会った[27]。これらの作品は、画家の周辺の環境における一般の人々の様子を描いており、その影響がタナーの作品にも表れている。タナーの『若い木靴職人』(1895年)にはクールベの『石割人夫』(1850年)の影響が見られ、どちらの作品も徒弟制度と肉体労働をテーマにしている[27]。

タナーは当初、海景画で海と人間との格闘を描いていたが、1895年からは主に宗教画を描くようになった。この時期、タナーは精神的な葛藤を経験していた。1896年のクリスマスにタナーが両親に宛てた手紙には、「私は彼(神)にもっと忠実に仕える決心をした」と書かれている[32]。その過渡的な作品として、波に翻弄される漁船を描いた作品があり、スミソニアン・アメリカ美術館に所蔵されている[33]。

1896年のサロン・ド・パリで、タナーの『ライオンの穴の中のダニエル』が入選した[15]。その年の暮れに描いた『ラザロの復活』は、翌1897年のサロンで3位となり、フランス政府に購入され、現在はオルセー美術館に所蔵されている[34]。美術評論家で、「現代宗教美術の主要なパトロン」[35]だったロッドマン・ワナメイカーは、『ラザロの復活』を見て[36]、タナーに対し、旅費を全額出すので中東へ行ってみてはどうかと申し出た[15]。ワナメイカーは、聖書の場面を描く画家は、その舞台となった環境を直接見ておくべきだと考えており、タナーはその投資に十分に値すると考えたのだった。タナーはその申し出を受け入れた[35]。タナーは1897年の4か月間、1898年から1899年にかけての6か月間、パレスチナと北アフリカの観光ルートを周り、途中乾燥地帯ではテントを張った[35]。

眼精疲労のため、1907年のサロンには出品しなかった。1908年のサロンには、1906年から制作を始めてこの年に完成した『賢者と愚かな乙女』を提出した。1908年にはニューヨークでの個展に集中していたことから、1909年のサロンには出品しなかった。1910年から1913年までのサロンにも出品をしていないものと見られる[37]。タナーは1910年に、「サロンで自分の絵が隅に追いやられたのは、誰の目から見ても侮辱であり、もう二度とサロンには出展しないだろう」と発言していた[37]。これは、アメリカ合衆国がフランスの絵画に対し高い関税をかけていることに対する報復だったとみられる[37]。

タナーの母が亡くなり[38]第一次世界大戦が勃発した1914年、タナーは数年ぶりにサロンに出展し、1912年に描いた『ラザロの家のキリスト』と『マリア』を提出した[39][38]。

晩年

[編集]

第一次世界大戦中、タナーは赤十字社広報部に勤務し、前線の様子を描いた[40]。戦場のアフリカ系アメリカ人部隊を描いた作品は、当時としては珍しかった。1923年、フランス政府はタナーの芸術家としての功績を讃えてレジオンドヌール勲章シュヴァリエを授与した。

1927年頃、タナーはパリで、同じアフリカ系アメリカ人芸術家であるパルマー・ヘイデンと出会った。彼らは芸術の技法について議論し、タナーはヘイデンに、フランス社会との関わり方について助言した[41]。タナーはまた、フランスで学んでいた他の芸術家にも影響を与えた。その中には、ヘール・ウッドラフ、ロマレ・ビアードンなどの黒人抽象主義の芸術家も含まれる[17]。

タナーの絵画のいくつかは、アトランタの美術収集家J・J・ハバティーが購入した。ハバティーはハバティー・ファーニチャーの創業者であり、ハイ美術館の設立に尽力した。タナーの『エタプルの漁師』は、ハバティーのコレクションの一つであり、現在はハイ美術館に常設展示されている。

タナーは、1937年5月25日にパリの自宅で亡くなった[40]。遺体はパリ郊外、オー=ド=セーヌ県ソーのソー墓地に埋葬されている。

私生活

[編集]

タナーは1899年にスウェーデン系アメリカ人のオペラ歌手、ジェシー・オルソン(Jessie Olsson)と結婚した[42]。同時代の画家であるヴァージニア・ウォーカー・コースは2人の関係について、才能の面では対等だが、人種的な観点からは釣り合わないと述べている。

ファン、ポートランドのオルソン嬢について聞いたことがあるか? 彼女は美しい声を持っていると私は思うし、彼女はそれを磨くためにパリに来たのだと思う。そして彼女は黒ん坊のアーティスト(darkey artist)と結婚した。彼は素晴らしい才能を持った男だが、黒人だ。彼女は教養があって本当に素敵な女性のようだが、教養のある女性があんな男と結婚するのを見ると気分が悪くなる。彼の作品は知らないが、才能はあるらしい[43]。

妻ジェシーは、夫よりも12年早い1925年に亡くなった。タナーは1920年代を通して妻の死を深く悲しんだ。妻の死後、タナーは一家で住んでいたレ・シャルムの家を売却した。妻ジェシーの遺体は、ソー墓地の夫の隣に埋葬されている[44]。

2人の間にはジェシー(Jesse)という息子がおり、タナーの死去の時点で存命だった[22]。

絵画のスタイル

[編集]

タナーは、エイキンズの作品を思わせるような写実主義のスタイルで、風景画、宗教画および日常生活の場面を描いた[45][46]。『バンジョーのレッスン』などはアフリカ系アメリカ人の日常生活を描いたものだが、その後は宗教画を描くようになった[22]。これは、聖職者だった父の影響と考えられる[15]。

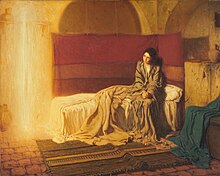

タナーは、絵画やデッサンにおいて特定のアプローチに制限されることはなかった。タナーの作品には、細部にまで最新の注意が払われた描写と、自由で表現力豊かな筆遣いが反映されているものとがあり、多くの場合、両方の手法が同時に用いられている。タナーは、絵画における色彩の効果にも興味を持っていた[47]。『ラザロの復活』(1896年)や『受胎告知』(1898年)のような暖色系の構成は、宗教的な瞬間の激しさと熱意、神と人間との間の超越性の高揚感を表現したものである。『三人のマリア』(1910年)、『タンジェの門』(1912年)、『凱旋門』(1919年)など、1890年代半ば以降の作品では、「タナー・ブルー」と呼ばれる特徴的な藍色とターコイズブルーが使われ、寒色系の色調が強調されるようになった[26]。『善き羊飼い』(1903年)や『聖女の帰還』(1904年)などの作品は、厳粛な宗教性と内省的な雰囲気を喚起する。

タナーは作品の中で光を用いた試みをよく行い、それに象徴的な意味合いを加えることもあった。例えば『受胎告知』(1898年)では、大天使ガブリエルが光の柱として表現され、左上隅の棚の上端と併せて十字架のように見える[48]。

友人と同僚

[編集]タナーの友人や同僚には、ハーモン・アトキンス・マクニール(彫刻)、ハーマン・ダドリー・マーフィー(風景画)、ポール・ゴーギャン(総合主義)、マイロン・G・バーロウ(風俗画)、チャールズ・ホーヴェイ・ペッパー(日本式木版画)、シャルル・フィリジェ(象徴主義)、アルマン・セガン(ポスト印象派)、ヤン・ヴェルカーデ(ポスト印象派、キリスト教象徴主義)、ポール・セリュジエ(抽象芸術)、ギュスターヴ・ロワゾー(ポスト印象派)などがいた[17][49][50]。

遺産

[編集]

タナーは「史上最も偉大なアフリカ系アメリカ人画家」と呼ばれている[52]。フランスでタナーから指導を受けたウィリアム・エドワード・スコットの作品には、タナーの技法の影響が見られる[27]。ノーマン・ロックウェルのイラストの中には、タナーが求めたのと同じテーマや構図のものもある。例えば、ロックウェルが1922年に制作した『リテラリー・ダイジェスト』誌の表紙は、タナーの『バンジョーのレッスン』の影響を強く受けたと見られる[27]。タナーが指導した他の主要なアーティストには、ウィリアム・A・ハーパーやヘール・ウッドラフなどがいる[9]。

タナーの『夕暮れの砂丘、アトランティックシティ』(1885年頃)は、ホワイトハウスのグリーンルームに掲げられている。これは、アフリカ系アメリカ人アメリカ人の作品としては初めて、ホワイトハウスの常設コレクションとして購入されたものである。この作品は、ビル・クリントン政権時代にタナーの親族のセイディ・タナー・モッセル・アレクサンダーから10万ドルで購入されたもので、ホワイトハウスの常設コレクションとして購入された初のアフリカ系アメリカ人アーティストの作品である[53]。

受賞

[編集]

- 1895年 綿花州万国博覧会(アトランタ): 『バグパイプのレッスン』で銅メダル[54]

- 1896年 サロン・ド・パリ: 佳作[55] for Daniel in the Lions' Den[56]

- 1897年 サロン・ド・パリ: 第三等メダル[55] for Raising of Lazarus[57]

- 1899年 フィラデルフィア美術アカデミー: ウォルター・リッピンコット賞[55] for Christ and Nicodemus on a Rooftop[57]

- 1900年 パリ万国博覧会: 『ライオンの穴の中のダニエル』で[56]銀メダル[55][58]

- 1901年 パン・アメリカン博覧会(ニューヨーク州バッファロー): 『ライオンの穴の中のダニエル』で[56]銀メダル[55][58]

- 1904年 セントルイス万国博覧会: 『ライオンの穴の中のダニエル』で[56]銀メダル[55][58]

- 1906年 サロン・ド・パリ: 『エマオの弟子たち』で第二等メダル[56]

- 1906年 シカゴ美術館: 『墓の前の二人の弟子』でノーマン・ウェイト・ハリス銀メダル[55][59][57]

- 1915年 サンフランシスコ万国博覧会: 『ラザロの家にいるキリスト』[56]で金メダル[55][58]

- 1922年: レジオンドヌール勲章シュヴァリエ[55](第一次世界大戦中の赤十字の一員としての功績に対して)[60]

- 1927年 全米美術クラブ(ニューヨーク): 『エジプトへの逃亡(門にて)』で銅メダル[56]

- 1930年 グランド・セントラル・アート・ギャラリー(ニューヨーク): 『エタプルの漁師』ウォルター・L・クラーク賞[57][56]

主な作品

[編集]

- Seascape-Jetty (c. 1876–78)

- Pomp at the Zoo (1880). Private Collection

- Joachim Leaving the Temple (c. 1882–1888). ボルチモア美術館

- Boy and Sheep Lying under a Tree (1881). 個人蔵(フィラデルフィア美術館で展示)

- Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City (1886). セイディ・タナー・モッセル・アレクサンダーからホワイトハウスが購入

- バグパイプのレッスン The Bagpipe Lesson (1893). ハンプトン大学美術館

- バンジョーのレッスン The Banjo Lesson (1893). ハンプトン大学美術館

- The Thankful Poor (1894). Art Bridges[61]

- 若い木靴職人 The Young Sabot Maker (1895). ネルソン・アトキンス美術館

- ライオンの穴の中のダニエル Daniel in the Lions' Den (1895). ロサンゼルス・カウンティ美術館

- ラザロの復活 The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896). オルセー美術館

- Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1897). ボルチモア美術館

- 砂漠のライオン Lions in the Desert (c. 1897–1900). スミソニアン・アメリカ美術館

- 受胎告知 The Annunciation (1898). フィラデルフィア美術館

- Moonlight Landscape (1898–1900). Muscarelle Museum of Art, Williamsburg, VA.[62]

- 善き羊飼い (1903). Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University

- 聖女の帰還 (1904). Cedar Rapids Art Gallery, Iowa

- 墓の前の二人の弟子 (1905–06). シカゴ美術館

- The Visitation (1909–10). Kalamazoo Institute of Arts

- 聖家族 (1909–10). Muskegon Museum of Art, Michigan, Hackley Picture Fund

- モロッコの風景 (about 1912). バーミンガム美術館

- タンジェの司法宮殿 (1912–13). Smithsonian American Art Museum[63]

- Scene in Cairo. マビー・ゲラー美術館

ギャラリー

[編集]-

Pomp at the zoo, circa 1880

-

Pomp at the Philadelphia Zoo, circa 1880-1886

-

Sister Sarah, 1882.

-

西インドから来た女性 Woman from the West Indies, 1891, Brittany, France.[64]

-

バグパイプのレッスン The Bagpipe Lesson, 1893

-

若い木靴職人 The Young Sabot Maker, 1895

-

1895. Marshes in New Jersey; possibly the "pastel of New Jersey coast by moonlight" exhibited at the 1895 Salon with The Young Sabot Maker.[56]

-

The Annunciation to the Shepherds, c. 1895

-

ラザロの復活 The Resurrection of Lazarus, 1896. Won medal in 1897 Paris Salon, bought by French government.

-

View of the Seine, looking toward Notre Dame, 1896

-

Jesus and Nicodemus, 1899. Displayed at Paris Salon and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where it won a Walter Lippincott Prize.

-

The Savior, 1900–1905

-

Christ in the home of Mary and Martha, 1905

-

The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water, c. 1907

-

Angels Appearing before the Shepherds, c. 1910

-

Christ walking on the water. Engraving, possibly a show catalog, 1910.

-

A View of Fez, c. 1912

-

Fishermen at Sea, c. 1913

-

Mary, 1914

-

Coastal Landscape, France, 1919

-

1936. Tanner's final painting, Return from the Crucifixion. Mary and Joseph are in the front.

-

Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, c. 1885, ホワイトハウス

-

Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, 1929–30, ハイ美術館

脚注

[編集]- ^ “Henry Ossawa Tanner”. May 27, 2011時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 5, 2006閲覧。

- ^ “Artist Info”. www.nga.gov. November 25, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9

- ^ a b c Henry Ossawa Tanner. American, 1859 - 1937. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1919.html

- ^ The Civil War in America: Benjamin Tucker Tanner, Library of Congress Exhibitions

- ^ Kelly Jeanette Baker (2003年). “Race, Religion, and Visual Mysticism”. Florida State University. 2024年10月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Homespun Heroines and other women of distinction. New York: Oxford University Press. (1988). pp. 32–33

- ^ a b “Mother of Henry O. Tanner”. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 2024年10月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Woods, Naurice Frank (2018). Henry Ossawa Tanner Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-138-24194-7

- ^ Wright, A. J. (May 18, 2017). “Halle Tanner Dillon”. Encyclopedia of Alabama. November 8, 2020閲覧。

- ^ Angelica Villa (November 29, 2022). “Preservationists Move to Save Painter Henry Ossawa Tanner's Childhood Home in Philadelphia”. ARTnews

- ^ a b Finkelman, Paul, ed (2006). Encyclopedia of African American History 1619–1895. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 224

- ^ Tanner, Henry Ossawa; Marley, Anna O. (2012) (英語). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit. Univ of California Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-520-27074-9

- ^ Parry, Ellwood C. III. Three Nineteenth Century Afro-American Artists. Cedar Rapids, IA: Cedar Rapids Art Center, 1980.

- ^ a b c d Matthews, Marcia. Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1969.

- ^ Woods, Naurice Frank Jr. (July 6, 2017) (英語). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy. Taylor & Francis. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-315-27948-0

- ^ a b c Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 20–21, 59, 90. 93. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9

- ^ Schantz, Michael (October–November 2005). “Thomas Hovenden: American Painter of Hearth and Homeland”. American Art Review. オリジナルの16 June 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。. "[note: reprinted in Resource Library on April 22, 2009, with permission of the author and the Woodmere Art Museum, which was granted to TFAO on April 1, 2009]"

- ^ “Henry Ossawa Tanner | Smithsonian American Art Museum” (英語). americanart.si.edu. June 4, 2021閲覧。

- ^ a b Bruce, Marcus C. Henry Ossawa Tanner. New York: Crossroad Publishing, 2002.

- ^ Matthews, Marcia (1994). Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-226-51006-9.

- ^ a b c “Henry Ossawa Tanner”. Springfield Museum of Art. January 10, 2006時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 5, 2006閲覧。

- ^ Tanner, Henry Ossawa (July 1909). “Story of an artist's life I.”. The World's Work 18 (3): 11666.

- ^ a b Tanner, Henry Ossawa (July 1909). “Story of an artist's life II. Recognition”. The World's Work 18 (3): 11770. "As I now look back, it seems curious to me that I should have been able to arrive at thirty years of age with two years of that time in Paris and never to have heard of the Salon or, having heard of it, not to have at all realized its importance in the Art world... What a surprise awaited me in the court of that old palais! Hundreds of statues that appeared to me nearly all of them fairer than the “Venus de Milo” and upstairs the paintings — thousands of them — and nearly all of them much more to my taste than were the old masters of the Louvre... Here was something to work for, to get a picture here. This now furnished a definite impetus to my work in Paris — to be able to make a picture that should be admitted here — could I do it?"

- ^ Khalid, Farisa. Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson. SmartHistory. The Center for Public Art History. https://smarthistory.org/tanner-banjo/

- ^ a b Farrington, Lisa (2017). African-American Art A visual and Cultural History. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-19-999539-4

- ^ a b c d e f Shaw, Thomas M. What Manner of Men? A Reconsideration across the Synapses of Art History of Three Paintings and their Images of Men of African Descent. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997.

- ^ Woods, Naurice Frank, Jr., Ph.D. Insuperable Obstacles: The Impact of the Creative and Personal Development of Four Nineteenth Century African American Artists. The Union Institute, 1993.

- ^ Woods, Naurice Frank Jr. (2018). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-315-27948-0

- ^ Bearden, Romare; Henderson, Harry Brinton (1972). Six Black Masters of American Art. Zenith Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-385-01211-9

- ^ “Atherton Curtis letter to Jessie Tanner after the death of H. O. Tanner in 1937”. 2024年10月11日閲覧。

- ^ Woods, Naurice Frank. "Embarking on a New Covenant: Henry Ossawa Tanner's Spiritual Crisis of 1896." American Art, vol. 27, no. 1, 2013, pp. 94–103. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/670686.

- ^ Details on the museum site

- ^ “Negro Artist site”. Negroartist.com. December 14, 2013閲覧。

- ^ a b c Richmond-Moll, Jeffrey. Souvenir from the Holy Land: On Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Abraham’s Oak. Smithsonian American Art Museum. https://americanart.si.edu/blog/art-bites-tanners-abrahams-oak

- ^ “Negro Artist site”. Negroartist.com. December 14, 2013閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Artists Allege Discrimination out of Revenge”. The Montreal Star (Montreal, Quebec, Canada): p. 3. (2 July 1910)

- ^ a b Tanner, Henry Ossawa. Mary, ca. 1914, oil on canvas, 45 1⁄2 x 34 3⁄4 in. (115.5 x 88.2 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Dorothy L. McGuire, 1991.102. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/mary-32409

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F. Henry Ossawa Tanner. First trade edition. Philadelphia, PA : Philadelphia Museum of Art ; New York, NY : Rizzoli International Publications. 1991.

- ^ a b “Henry Ossawa Tanner”. August 29, 2006時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 9, 2006閲覧。

- ^ Finkelman, Paul, ed (2009). Encyclopedia of African American History (1896 to the present). 2. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 393

- ^ Marley, Anna O. "Introduction" in Modern Spirit Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia. 2012.

- ^ Course, Virginia Walker qtd. by Jean-Claude Lesage in "Tanner, the Pillar of Trepied". Modern Spirit. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia. 2012, p. 88.

- ^ Marley (2012), p. 41.

- ^ “Henry Ossawa Tanner Online”. August 5, 2006閲覧。

- ^ “Realism – Realism Art”. October 7, 2009時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 5, 2006閲覧。

- ^ Kettlewell, James K. The Art of Henry Ossawa Tanner. Glen Falls, NY: The Hyde Collection, 1975.

- ^ “Teacher Resources: The Annunciation”. The Annunciation, Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. June 6, 2016閲覧。

- ^ “Henry Ossawa Tanner papers, 1860s-1978, bulk 1890-1937 311: Photographs of Artwork, circa 1920s”. Smithsonian Archives of American Art. 2024年10月11日閲覧。 “[note: image download number 54] To my dear Henry Tanner Charles H. Pepper Paris '99”

- ^ “Henry Ossawa Tanner papers, 1860s-1978, bulk 1890-1937: Henry Tanner and family dining outdoors, 1907 or 1908”. Smithsonian Archives of American Art. 2024年10月11日閲覧。 “[note: image download numbers 1 and 2] Jesse Tanner, Mrs. Tanner, Barlow, Henry Tanner”

- ^ “A modest improvement at the National Gallery | Tyler Green: Modern Art Notes | ARTINFO.com”. Blogs.artinfo.com (February 3, 2012). December 14, 2013閲覧。

- ^ Finkelman, Paul, ed (2006). Encyclopedia of African American History 1619–1895. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 101

- ^ "White House Announces Acquisition of Henry Ossawa Tanner Painting for Permanent White House Collection" Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Life in the White House.

- ^ Carlyn G. Crannell Romeyn (Winter 1983–1984). “Henry O. Tanner: Atlanta Interlude”. The Atlanta Historical Journal 27 (4): 38. "On the other hand, it is possible that some of tanner's Atlanta friends secured the three works (including The Bagpipe Lesson which won a bronze medal) for this exposition."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “Henry Ossawa Tanner — Artist”. The Northwestern Bulletin-Appeal (Saint Paul, Minnesota): p. 2. (July 25, 1925)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9. "1895 May. Paris, Salon. Intérieur Bretagne [Brittany Interior], Le Jeune Sabotier [The Young Sabot Maker], pastel of New Jersey coast by moonlight."

- ^ a b c d “Henry Ossawa Tanner 1859/1937”. Detroit Free Press: pp. 284–285. (July 14, 1991)

- ^ a b c d “Noted artist dies abroad”. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania): p. 17. (May 27, 1937)

- ^ American Oil Paintings and Sculpture: 28th Annual Art Exhibition, Art Institute of Chicago November 16, 1915 to January 2, 1916

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F.; Sewell, Darrell; Alexander-Minter, Rae (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner: catalogue. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art. p. 32. ISBN 0-87633-086-3

- ^ “The Thankful Poor”. Art Bridges. March 3, 2021閲覧。

- ^ “Moonlight Landscape, (oil on canvas).”. Art in Bloom. Muscarelle Museum of Art (2016年). June 20, 2018閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ “Palace of Justice, Tangier, Morocco”. World Digital Library (1890–1900). June 27, 2013閲覧。

- ^ “Henry Ossawa Tanner Lot 41: Henry Ossawa Tanner, (American, 1859-1937), Woman from the French West Indies, c. 1891”. 2024年10月11日閲覧。 “The artist arrived in Paris, France at this time and spent the summers on the west coast in Brittany. There, he adopted a predominately green palette with an emphasis on vertical brushstrokes as can be seen in the Woman from the French West Indies...we are looking at an image of a light-skinned woman from one of the islands of the French West Indies-Martinique, Guadeloupe or Dominica. This claim is supported by her costume and headdress.”

- ^ Mathews, Marcia M (1969). Henry Ossawa Tanner, American artist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 69–74

- ^ Henry Ossawa Tanner (July 1909). “The Story of an Artist's Life: II Recognition”. The World's Work (Open Court Publishing Co) 18 (3): 11772. "In 1895, I painted "Daniel in Lions' Den."...It was exhibited in the Salon of 1896.."

参考文献

[編集]- Anna O. Marley, ed. Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (University of California Press: 2012).

- Marcia M. Matthews, Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (University of Chicago Press: 1995).

- Kristin Schwain, Signs of Grace: Religion and American Art in the Gilded Age (Cornell University Press: 2007).

- Will South, “A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 8. issue 2 (Autumn 2009).

- Judith Wilson, “Lifting ‘The Veil’: Henry O. Tanner’s The Banjo Lesson and The Thankful Poor,” Contributions in Black Studies: A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies, volume 9, article 4.

関連項目

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]- White House Biography

- Springfield Museum of Art Biography

- Ebony Society of Philatelic Events and Reflections Biography

- Muskegon Museum of Art

- Profile at PBS.org

- Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (University of California Press, 2012)—the most complete scholarly publication to date produced in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), Tanner's alma mater

- Biographical sketch and gallery at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- Art online

- Henry Ossawa Tanner Papers

- Alexander family papers relating to Henry Ossawa Tanner, 1912–1985

- Gallery of images and letters from the PAFA archives Archived April 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- Henry Ossawa Tanner papers, 1860s–1978, bulk 1890–1937. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

![西インドから来た女性(英語版) Woman from the West Indies, 1891, Brittany, France.[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Woman_from_the_West_Indies%2C_by_Henry_Ossawa_Tanner.webp/169px-Woman_from_the_West_Indies%2C_by_Henry_Ossawa_Tanner.webp.png)

![1895. Marshes in New Jersey; possibly the "pastel of New Jersey coast by moonlight" exhibited at the 1895 Salon with The Young Sabot Maker.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Marshes_in_New_Jersey%2C_by_Henry_Ossawa_Tanner._SAAM-1984.149.3_1.jpg/170px-Marshes_in_New_Jersey%2C_by_Henry_Ossawa_Tanner._SAAM-1984.149.3_1.jpg)

![Daniel in the Lions' Den, 1907–1918. The original (now lost) was painted in 1895 and displayed in the 1896 Salon.[65][66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/Daniel_in_the_Lions%27_Den_LACMA_22.6.3.jpg/170px-Daniel_in_the_Lions%27_Den_LACMA_22.6.3.jpg)