リーリン

リーリン (Reelin) は、神経細胞の移動と発達中の脳での中での位置の固定の過程の制御を補助するタンパク質である。この初期の発達における重要な機能の他に、リーリンは成体においても長期増強の誘導によるシナプスの柔軟性の調節等を行う等、働きを続けている[5][6]。また、樹状突起[7]や樹状突起棘[8]の発達を促進し、脳室下帯等の成体の神経細胞新生箇所からの移動を調整し続ける。リーリンは脳だけで見られる訳ではなく、脊髄や血液、その他の器官や組織でも見られる。

リーリンは、いくつかの脳の疾患の発病に関わっていると指摘されている。例えば、統合失調症や双極性障害の患者の脳では、このタンパク質の発現量が少なくなっている。しかし、本当の原因は未だ不明であり、レベルが変化することを説明しようとする後生説[9]についても反対の証拠がいくつか挙がっている[10][11]。リーリンが全く欠如すると脳回欠損を引き起こす。また、アルツハイマー病や側頭葉てんかん、自閉症等にも関わっていると言われている。

発見[編集]

異常なふらつき歩行 (reeling gait) を見せるネズミの脳でこのタンパク質のRELN遺伝子が突然変異し、ホモ接合していることが発見されたことから、リーリンと名付けられた[12]。リーリンの機能の喪失に伴う主な表現型は、中枢神経系の発達過程における神経細胞の位置調整の失敗である。リーリンの遺伝子がヘテロ接合したネズミは、神経解剖学的な異常はほぼないものの、精神疾患と関連した中間表現型の特徴を見せる[13]。突然変異を誘発したネズミを使うことによって、中枢神経系の発達過程における分子機構に関する洞察を得ることができる。天然での有益な突然変異は、無意識行動を研究する学者によって最初に発見され、ケージの周囲での運動に障害を持つことから子孫を見分けるのは比較的容易であることが証明された。このようなネズミは多くの種類が発見され、その症状に応じて、reeler、weaver、lurcher、nervous、staggerer等の名前が与えられた。

reelerは、シャーロット・アワーバックの保持するネズミのコロニーの中からエディンバラ大学のダグラス・スコット・ファルコナーが発見し、1951年に最初に記述された[12]。1960年代の組織病理学の研究により、reelerの小脳はサイズ極端に小さくなっており、脳のいくつかの領域に見られる通常のラミナ組織が分離しているのが明らかになった[14]。1970年代には、大脳新皮質の細胞層が逆位していることが発見され[15]、reeler突然変異はさらに多くの注目を集めることとなった。

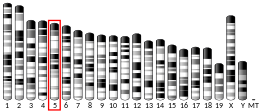

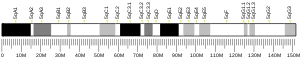

1994年、突然変異源処理によりreelerの新しい対立遺伝子が得られた[16]。これは遺伝子座の最初の分子マーカーとなり、RELN遺伝子は7q22染色体にマッピングされ、クローニングされた[17]。高知医科大学の日本人研究者は reelerの体内で通常の脳の抽出物に対する抗体を作り出し、後にこれらの抗体はリーリンのモノクローナル抗体に特異的であることが発見され、CR-50 (Cajal-Retzius marker 50)と名付けられた[18]。CR-50は当時機能未知だったカハール・レチウス細胞に特異的に働くとされている。

リーリンの受容体であるapolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) とvery-low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) は、細胞質の受容体タンパク質Dab1を研究していたTrommsdorff, Herzらによって発見された[19]。後に彼らは、ApoER2とVLDLRをともに破壊したノックアウトマウスは、reelerと似た皮質の層の異常を見せることを示した[20]。

リーリンの下流の経路の研究は、yotariやscrambler等、他の異常行動を示すネズミの解明にも役に立った。これらの突然変異種は、reelerと同じような表現型を示すが、リーリンの突然変異は持たない。その後、yotariではDab1遺伝子が欠け、scramblerではほとんど検出されないことが明らかとなり、ネズミのdisabled homologue 1 (Dab1) 遺伝子はこれらの突然変異種の表現系を支配していることが示された[21]。Dab1の標的破壊はreelerと同様の表現系を示すことも分かった。

続いて、リーリンの遺伝的多様性と統合失調症、アルツハイマー病、自閉症等の高度な機能不全との間の関係を推測する一連の論文が出された。このタンパク質をコードする遺伝子が発見されて13年後の2008年時点で、タンパク質の構造や機能の様々な面に焦点を当てた数百の科学論文が投稿された[22]。2008年に出版された"Reelin Glycoprotein: Structure, Biology and Roles in Health and Disease"という本では、これらの論文の概要がまとめられている[23]。

組織分布と分泌[編集]

研究によると、リーリンはシナプス小胞には存在せず、分泌経路を通って分泌され、ゴルジ体に蓄えられることが分かっている[24]。リーリンの放出速度は脱分極の影響を受けないが、その生成速度に厳密に依存する。これは、他の細胞外マトリックスタンパク質の分泌の過程と類似している。

脳の発達の期間は、リーリンはいわゆるカハール・レチウス細胞、カハール細胞、レチウス細胞によって大脳皮質と海馬で分泌される[25]。リーリンの発現する胎児や新生児の脳の細胞では、皮質の境界領域や軟膜下果粒層[26]、海馬の網状分子層や歯状回の上部境界領域で多く見られる。

発達中の小脳では、リーリンは顆粒状細胞が顆粒状細胞層の内側に移動する前に、顆粒状細胞層外側で発現する[27]。

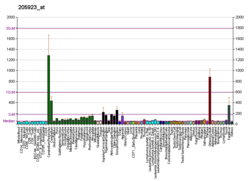

リーリンの合成は誕生直後にピークを迎え、その発現量は急激に減少し、発現部位も分散する。成体の脳では、皮質のγ-アミノ酪酸作動性介在神経細胞や小脳のグルタミン酸作動性神経細胞[28]、また少量であるがカハール・レチウス細胞で発現する。GABA作動性介在神経細胞やマルティノッティ細胞では、リーリンはカルレチニンやカルビンディンより遥かに多い量が検出されるが、シャンデリア細胞や籠細胞等のパルブアルブミン発現細胞ではそれほどではない[29][30]。白質では、介在神経細胞のリーリン発現の割合はごく小さい[31]。脳の外では、成熟した哺乳類の血液、肝臓、下垂体中葉、副腎のクロム親和性細胞等で見られる[32]。肝臓では、リーリンは伊東細胞に局在している[33]。肝臓が損傷を受けるとリーリンの発現量が増え、回復すると発現量は元に戻る[34]。

目では、リーリンは網膜神経節細胞から分泌され、角膜内皮でも見られる[35]。肝臓と同じように、損傷を受けると発現量が増える。また、歯牙形成の際や永久歯の中で、歯髄の最外層にある象牙芽細胞でも生産される[36]。象牙芽細胞は、痛みの信号を神経末端に変換するセンサー細胞の役割も果たすという研究成果もある[37]。この仮説によると、リーリンは象牙芽細胞と神経末端の接触を促すことで[38]、この過程に関わっている[23]。

構造[編集]

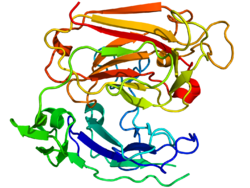

リーリンは、3,461アミノ酸残基、およそ388 kDaからなる細胞外マトリックスの糖タンパク質として分泌される。構造上の特徴から、酵素の役割を果たし、セリンプロテアーゼ活性を持つ[40]。ネズミのRELN遺伝子は、65個のエクソンから構成され、約450 bpに及ぶ[41]。タンパク質のC末端側でたった2つのアミノ酸をコードするエクソンは、選択的スプライシングを起こすが、正確な機能は分かっていない[23]。遺伝子構造の中に2つの転写開始部位と2つのポリアデニル化部位が同定されている[41]。

リーリンタンパク質は、27アミノ酸残基のシグナルペプチドで始まり、"SP"と表されるF-spondinと類似した領域が続き、その後に"H"と表されるリーリンに特異的な配列が存在する。その次に300-350残基のアミノ酸配列が8回繰り返す。これはreelin repeatsと呼ばれ、中心のEGFモチーフでAとBの2つのサブドメインに分割される。2つのサブドメインは直接接触し、構造はコンパクトになっている[42]。

リーリンのC末端側には、32残基と短く高塩基性の"+"と表される領域がある。この領域は非常に保存性が高く、調査された全ての哺乳類で100%の相同性を持っている。この領域はかつてはリーリンの分泌に不可欠であるとも考えられてたが、その後の研究で、分泌には関与しないことが明らかとなった[43]。

リーリンは生体内ではリピート3の中[44]、及びリピート6とリピート7の間[45]で切断され、3つの断片に分かれる[46]。このうち、リピート3の中の切断によってリーリンの活性は顕著に減少する[44]。リーリンのプロセッシングは、適切な皮質形成に必須であると提唱されたこともある[47]が、リピート3の中の切断を担う酵素ADAMTS-3の欠損マウスでは層構造形成が異常にはならないことも報告されている[48]。

機能[編集]

リーリンの第一の機能は、胎児期の皮質形成と神経細胞配置の調整であるが、他にも多くの過程に関わっていることが指摘され、研究は進展中である。

リーリンは多くの組織や器官で見られ、発現時期や活性の局在によって機能を分類することが可能である。

発達中には多くの非神経性の組織や器官でリーリンが発現するが、器官が形成された後には発現量は急激に低下する。ノックアウトマウスが大きな症状を見せないため、ここでのリーリンの役割はまだ良く分かっていない。非神経器官の成体での発現量は多くないが、器官が損傷を受けると顕著に増加する[34][35]。損傷時に発現量が増加するリーリンの機能については研究が進んでいるところである。

一方、中枢神経系の発達過程におけるリーリンの機能はさらに重要で研究もより進んでいる。この時期のリーリンは前駆細胞を放射状グリア細胞に分化させて繊維の方向を揃え、神経芽細胞の移動を導く役割を果たす[52]。繊維はリーリンの濃度の高い方に伸びるので、リーリンを分泌する細胞層の位置は重要である[51]。例えば、リーリンは海馬や内嗅皮質の層に特異的な結合の発達を調整する[53][54]。

哺乳類の皮質形成は、リーリンが主要な役割を果たすまた別の過程である。この過程では、プレプレートと呼ばれる一時的な層が境界領域に分かれ、これらの間の空間に裏返しの神経層ができる。新しく作られた神経が層を通過し1つ上の段に配されるこのような配置は、進化的に古い爬虫類の脳等と比べても哺乳類の脳に特異的なものである。reeler突然変異のネズミのようにリーリンが欠けると、皮質の層の順番が逆になり、より若い神経細胞が層を通過できなくなる。サブプレートの神経細胞は上層の神経細胞に進入できなくなり、通常は第二層に配置されるカハール・レチウス細胞等が混ざったいわゆるスーパーレイヤーを形成する。

皮質層の正しい配置に果たすリーリンの役割について、合意された考え方はまだない。リーリンは細胞の移動を止めるシグナルとして働くという当初の仮説は、細胞の解離を誘導することや[55]海馬に小さな顆粒状細胞の層を作る役割、神経芽細胞の移動がリーリンの豊富な領域を避ける事実等を説明することができた。しかし、リーリン分泌層が間違った位置になってしまってもネズミの皮質形成が通常に進むという実験事実[56]や成長円錐に対するリーリンの影響に関する証拠の欠如から、別の仮説も提唱されるようになった。そのうちの1つによると、リーリンは未知のシグナルカスケードによって細胞の感受性を高めるとされている。

リーリンは脊髄においても神経細胞の配置を正す役割を果たしているという研究もある。発現の局在や量は、交感神経の節前神経の運動に影響を与える[57]。

リーリンは神経細胞の前駆体の移動に対しても活性を持ち、皮質やその他の脳の構造の中で細胞を正しい位置に制御している。神経細胞の集団に対して解離シグナルとしての役割を持つという説もあり、細胞同士を分離させ、水平方向の移動から放射方向の移動へ向きを変えることができる[55]。解離によって移動中の神経細胞は移動の方向付けをしていたグリア細胞から引き離され、個々の細胞として最終的な目的地に向かって自律的に移動するようになる。

成体の神経系ではリーリンは、脳室下帯と歯状回という最も活発な2つの神経生成部位で主要な役割を果たす。いくつかの種では、脳室下帯の神経芽細胞は、吻側移動経路と呼ばれる経路を通って嗅球に達する。ここでリーリンが個々の細胞に解離させることで、個別にさらに遠くまで移動できるようになる。また移動の方向は水平方向から垂直方向に変化し、放射状グリア繊維を道標として用いるようになる。吻側移動経路に沿って、2つの受容体ApoER2及びVLDLRとそれらの細胞内アダプターDAB1は、恐らく新しく提案されたリガンドであるトロンボスポンジン1の影響によって[49]、リーリンに対して独立に機能するようになることを示す研究結果もある[59]。成体の歯状回では、リーリンは脳室下帯から定期的に粒状細胞層に到着する新しい神経細胞を整列させ、層が肥大しないように保っている[60]。

フランスの研究者によると[61]、リーリンはNMDA受容体の立体配置の発育変動、NR2Bを含む受容体の活動性の向上、シナプスに留まる時間の減少等にも関わっているとされている[62][63]。彼らは、これが、生後の発育期間の脳で観察される"NMDA - NR2Bスイッチ"の裏にある機構の一部だと信じている[64]。2009年の研究では、リーリンを分泌中のGABA作動性海馬神経細胞が、NR2Bを含むNMDA受容体の濃度を低く保つのに不可欠であることが示された[58]。

進化上の重要性[編集]

リーリンとDAB1の間の相互作用は、単層の有羊膜類から多層の現世哺乳類に至る皮質の構造進化に重要な役割を演じた[65]。研究によると、リーリンの発現量は皮質が複雑になるほど大きくなり、ヒトの脳で最大となる[66]。リーリンは、これまで調査された全ての脊椎動物の終脳に存在するが、発現パターンには大きなばらつきがある。例えば、ゼブラフィッシュにはカハール・レチウス細胞が全くなく、代わりに他の神経細胞から分泌される[67][68]。両生類では分泌細胞は層を形成せず、脳での放射状の移動は非常に少ない[67]。

皮質がより複雑になると、適切な層形成のために放射状グリア繊維に沿った移動がより重要になる。リーリン分泌層の出現はこの進化の過程に重要な意味を持つと考えられている[56]。この層の重要性に関しては、矛盾したデータがあるが[56]、リーリンの機構と相互作用する別のシグナルによる配置機構があると説明されるか[56]、または実験に使われたネズミは、局所的に合成する人間の脳と比べて、[26]非常に多量のリーリンを分泌していたと説明される[69]。

出生時にほとんどが消滅するカハール・レチウス細胞では、チンパンジーと比べてヒトの進化が最も大きいとされるHAR1遺伝子とリーリンが共発現する[70]。また、リーリン経路は現在も進化の途上にあることを示す証拠がある。2007年に初めて発見されたDAB1遺伝子の変異は、現在中国人に広がっているが、他の人種では見られていない[71][72]。

作用機構[編集]

SFK:Src family kinases.

JIP:JNK-interacting protein 1

リーリンの主な活性は、2つの低密度リポタンパク質受容体VLDLRとApoER2によって行われている。またα-3-β-1インテグリン受容体が、リーリンがVLDLR/ApoER2と結合する部位の反対側のN末端に結合することも示されている[74]。プロトカドヘリンCNR1がリーリン受容体の働きをするという提案もあったが[75]、誤りであることが証明されている[76]。

リーリン受容体は神経細胞とグリア細胞の両方に存在する。また、放射状グリア細胞ではApoER2は等量が発現するが、VLDLRは10分の1程度の発現量であるという報告もある[52]。また、グリア細胞のβ-1インテグリン受容体は、神経芽細胞の移動よりも神経細胞の層形成に重要な役割を果たすとも言われている[77]。細胞内受容体DAB1はNPxYモチーフを通じてVLDLR及びApoER2と結合し、リポタンパク質受容体を通してリーリンシグナルの伝達に関わる。リーリンはSrc[78]やFyn[79]キナーゼによってリン酸化されてアクチン細胞骨格の変形を促し、細胞表面のインテグリン受容体の比率に影響を与えて細胞接着を変化させる。DAB1はリン酸化されることによりユビキチン化が進み、最終的に分解される。これは、リーリン不在下でDAB1の濃度が高まることの説明になる[80]。このような負のフィードバックは、皮質の適切な層形成にとって重要であると考えられている[81]。VLDLRとApoER2は2つの抗体によって活性化され、DAB1をリン酸化するが、その後の分解やreeler表現系の症状の緩和には関わっていないようである。そしてこれは、シグナルの一部はDAB1と独立な系統で制御されていることを示している[76]。

脳回欠損に重要な役割を果たし、LIS1(PAFAH1B1)と呼ばれるタンパク質はVLDLRの細胞内画分と相互作用し、リーリン経路の活性化に反応することが示されている[73]。

2つの主要なリーリン受容体は、また別の役割を果たしているようである。ある研究によると、VLDLRは停止シグナルとして働き、ApoER2は後生の新皮質神経細胞の移動に不可欠であることが示されている[83]。

リーリン分子は、ジスルフィド結合を介したホモダイマーからなる巨大なタンパク質複合体を形成することが示されている[84][85]。ホモダイマーが形成されないと、体外でのDAB1のチロシン残基のリン酸化は効率的に進まない。さらにリーリンの2つの受容体はクラスターを作ることができ[86]、おそらく信号伝達の場面で大きな役割を果たして、細胞内受容体DAB1を二量体、もしくは多量体化する。このようなクラスター化は、リーリン自体の不存在下でもシグナルチェーンを活性化することが示されている[86]。

一方、リーリン自体はセリンプロテアーゼ活性を用いて他のタンパク質とつながるペプチド結合を切断して[40]細胞接着の強さを変え、移動の過程に影響を与えることができる。

リーリンに依存した長期増強の強化は、NMDA受容体と相互作用するApoER2によって引き起こされる。この相互作用は、ApoER2がエクソン19にコードされる領域を持つ時に起こる。ApoER2遺伝子は選択的スプライシングを経たもので、エクソン19を含む変異はより強い活性を示す[87]。ある研究によると、記憶を貯蔵する必要がある時には、RELN遺伝子の脱メチル化が加速し、海馬のリーリン発現量が急激に上昇するとされている[88]。

リーリンによる樹状突起成長の活性化は、一見Srcファミリーのキナーゼによって行われ、Crkファミリーのタンパク質の発現に依存しているように見えるが[89]、Crk、CrkLとチロシン残基がリン酸化されたDAB1とが相互作用することと整合している[90]。さらに、ほとんどの神経細胞にCrkとCrkLを欠くCre-loxP部位特異的組換えを導入したモデルマウスはreeler表現系を示すことが報告され[91]、Crk/CrkLはリーリンのシグナルチェーンの中でDAB1とAktの間に位置することが示唆されている。

また、リーリンはFABP7の発現を促進し、Notch-1のシグナルカスケードを活性化するという研究結果もある[82]。

さらに別の研究では、生体内での皮質形成は胎児神経細胞のリーリンに大きく依存し[82]、未知のメタロプロテアーゼがタンパク質の中央部分を切り出すと考えられている。また未知のいくつかのタンパク質切断過程も働いているかもしれない[92]。完全長のリーリンは細胞外マトリックス繊維の表面に蓄積し、その中央画分は下の方まで浸透していくことができる[47]。神経芽細胞は繊維の表面まで来ると高濃度の完全長リーリンの層に達することで移動が止まっている可能性もある[23]。

VLDLRとApoER2はリポタンパク質受容体スーパーファミリーに属し、その構造の中にNPxYモチーフと呼ばれる内部ドメインを持つ。受容体と結合すると、リーリンはエンドサイトーシスによって内部に取り込まれ、N末端断片が再分泌される[93]。また別の研究によると、この断片は生後にリーリン受容体の経路とは独立に、皮質層II/IIIの錐体神経細胞の先端樹状突起の異常成長を妨げるとされている[94]。

ある研究グループは、リーリンシグナルにより、アクチンと相互作用するCofilin 1タンパク質のser3残基がリン酸化されると報告している。これによりアクチン細胞骨格が安定化して神経芽細胞を固定し、さらなる成長を妨げる[95][96]。

Cdk5との相互作用[編集]

神経細胞の移動及び配置を制御する主要なタンパク質であるサイクリン依存性キナーゼ5(Cdk5)は、DAB1やタウタンパク質等のその他のリーリンシグナルの細胞質標的をリン酸化することが知られている[97][98][99]。タウタンパク質はDAB1の標的の1つであるLis1とともに[100]、リーリンに誘導されて不活性化するGSK3B[101]やNUDEL[102]によっても活性化する。リーリンによる海馬での長期増強は、p35ノックアウトでは見られない[103]。p35はCdk5の重要な活性化因子であり、 p35/Dab1, p35/RELN, p35/ApoER2, p35/VLDLRの二重ノックアウトでは神経細胞の移動距離の不足が増大し[103][104]、通常の皮質形成においてはリーリン→ApoER2/VLDLR→DAB1の経路とp35/p39→Cdk5の経路が相乗作用することを示唆する。

病理学的役割[編集]

脳回欠損[編集]

RELN遺伝子の分裂は、ノーマン・ロバート症候群と呼ばれる、小脳形成不全を伴う珍しい脳回欠損の原因となると考えられている[105][106]。RELNのmRNAのスプライシングを分裂させる変異では、リーリンの生産量は非常に小さくなる。このような患者の表現型は、低血圧、失調、発達障害等で特徴付けられ、支えなしで座れなかったり言葉の発達がほとんどなかったりという症状を伴う。また先天性リンパ水腫が発症する。2007年には新しい染色体転座がこの症状の原因となっていることが発見された。ヒトのリーリンに影響を与える突然変異は、通常近親婚と関連付けられる。

統合失調症[編集]

統合失調症患者の脳におけるリーリンとそのmRNAの発現量の減少については、1998年[107]と2000年[108]に報告され、海馬[109]、小脳[110]、大脳基底核[111]、皮質[112][113]の検視分析によってそれぞれ独立に検証された。減少量は脳の領域によっては50%にも達し、グルタミン酸をGABAに変換する反応を触媒するGAD-67の発現量の減少も伴う[110]。統合失調症や気分障害では、リーリンとそのアイソフォームの血中濃度も変化するという報告もある[114]。統合失調症患者の前頭葉でのリーリンmRNAの発現量の減少は、Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortiumによって2001年に14の研究所で行われた研究で統計的に確かめられた[115]。

双極性障害[編集]

DNMT1と共同の上方調節によるRELNの発現量の減少は、精神病を伴う双極性障害に典型的な特徴であるが、精神病を伴わないうつでは見られず、精神病に特異的な変化と言うことができる[108]。統合失調症とは異なり、この変化は皮質だけで見られ、大脳基底核等の深部ではDNMT1濃度は平常で、リーリンとGAD67の濃度も通常の範囲に収まっている[111]。

自閉症[編集]

自閉症は、環境因子によって引き起こされる様々な箇所での突然変異が原因になると信じられている神経発達障害である。

当初より、自閉症とイタリア人に見られる多型であるRELN遺伝子の5' ATG開始コドンの前に現れるGGC/CGG繰返し配列との間の関係性が示唆されてきた。つまり5'領域の繰返し配列が長いほど、自閉症になりやすいと考えられてきた[116]。しかし、193の家系を調査した別の研究によると、繰返し配列の長さに有意な差は見られなかったという。

側頭葉てんかん[編集]

側頭葉てんかんの患者の海馬組織のサンプルでのリーリンの発現量の減少が、患者の45%-73%で見られる主な特徴である顆粒状組織の分散の範囲と直接関連しているということが発見されている[117][118]。小規模実験により、この分散はRELNのプロモーターの過剰メチル化と関連していることが分かっている[119]。

アルツハイマー病[編集]

リーリンの受容体ApoER2とVLDLRは、LDL遺伝子ファミリーに属している[120]。このファミリーの受容体は全てがアポリポタンパク質Eの受容体である。そのため、これらはしばしばApoE受容体と略される。ヒトはApoEの3つのアイソフォーム (E2, E3, E4) を持ち、このうちApoE4はアルツハイマー病のリスク因子となる。ApoE4はアルツハイマー病の発病で中心的な役割を果たすという説が出されている[120][121]。ある研究によると、アルツハイマー病の患者ではリーリンの発現とグリコシル化のパターンが変わっているという結果もある。

がん[編集]

腫瘍中ではDNAメチル化のパターンがしばしば変わっており、RELN遺伝子も影響を受けている可能性がある。膵癌では、リーリン経路のその他の物質と同時にリーリンの発現が抑制されているという研究結果もある[122]。また同じ研究で、リーリンの発現が残っているがん細胞の経路を切ることで、運動性や侵襲性が増加したとも言われている。一方、前立腺癌では、RELNの発現は過剰になり、グリーソン分類と相関する[123]。網膜芽細胞腫でもリーリンの過剰発現が確認されている[124]。

その他[編集]

全ゲノム相関解析によって、RELN遺伝子の変異が中耳の骨の発育異常である耳硬化症の原因にもなっている可能性が示唆された[125]。

リーリンの発現に影響を与える因子[編集]

リーリンの発現は、カハール・レチウス細胞の数に加え、多くの因子によって調整されている。例えば、TBR1転写因子は、T-elementを持つ他の遺伝子とともにRELN遺伝子の発現を制御している[127]。さらに高いレベルでは、妊婦管理がラットの子供の海馬[128]と皮質[126]でのリーリン発現と相関していることが報告されている。また、コルチコステロンに長く晒されることで、ネズミの海馬でのリーリン発現量が著しく低下したという報告もあり、うつ病におけるコルチコステロンの役割が指摘されるようになった[129]。ヒトの新皮質では、思春期を過ぎるとRELN遺伝子のメチル化が思春期前と比べて増加したという研究結果もある[129]。

向精神剤[編集]

リーリンは多くの種類の脳の疾患に関わっており、また通常は生後に測定さるため、薬物効果を評価することが重要である。

後成仮説によると、脱メチル化の平衡を変える薬物は、メチル化によるRELN及びGAD67の下方制御を緩和することができる。ある研究によると、クロザピンやスルピリドは、L-メチオニンで処理した両方の遺伝子の脱メチル化を促進したが[130]、ハロペリドールやオランザピンにはそのような効果はなかった。ヒストンの脱アセチル化阻害剤であるバルプロ酸は、抗精神病薬とともに摂取すると有益であると提案されている。しかし、後成仮説の主要な前提と矛盾する研究もある。またFatemiらによる研究では、バルプロ酸によるリーリン発現量の増加は確認されず、さらなる研究の必要性が示唆されている。

Fatemiらは、下記の薬剤を21日間に渡り腹腔内に注射した後、前頭葉皮質のRELN mRNAとリーリンタンパク質の量を測定し、次の結果を得た[23]。

| リーリン発現 | クロザピン | フルオキセチン | ハロペリドール | リチウム | オランザピン | バルプロ酸 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| タンパク質 | ↓ | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↔ |

| mRNA | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

2009年、Fatemiらは同じ薬剤を用いてさらに詳細な研究を行った成果を公開した。この研究では、リーリン自体の他に、シグナルチェーン上のVLDLR、DAB1、GSK3beta等の遺伝子の皮質での発現量が測定され、さらにGAD65とGAD67についても調べられた[131]。

相互作用[編集]

リーリンは、VLDLR及びApoER2とタンパク質間相互作用をすることが示されている[132][133]。ApoER2は、低比重リポタンパク質受容体関連タンパク質8 (Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8) としても知られている[134][135]。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000189056 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000042453 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ Weeber EJ, Beffert U, Jones C, et al. (October 2002), “Reelin and ApoE receptors cooperate to enhance hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning”, J. Biol. Chem. 277 (42): 39944–52, doi:10.1074/jbc.M205147200, PMID 12167620W

- ^ D'Arcangelo G (August 2005), “Apoer2: a reelin receptor to remember”, Neuron 47 (4): 471–3, doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.001, PMID 16102527

- ^ Niu S, Renfro A, Quattrocchi CC, Sheldon M, D'Arcangelo G (January 2004), “Reelin promotes hippocampal dendrite development through the VLDLR/ApoER2-Dab1 pathway”, Neuron 41 (1): 71–84, doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00819-5, PMID 14715136

- ^ Niu S, Yabut O, D'Arcangelo G (October 2008), “The Reelin signaling pathway promotes dendritic spine development in hippocampal neurons”, J. Neurosci. 28 (41): 10339–48, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1917-08.2008, PMC 2572775, PMID 18842893

- ^ Grayson DR, Guidotti A, Costa E (2008年1月17日). “Current Hypotheses”. Schizophrenia Research Forum. schizophreniaforum.org. 2008年9月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ Tochigi M, Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Komori A, Sasaki T, Kato N, Kato T (2007), “Methylation Status of the Reelin Promoter Region in the Brain of Schizophrenic Patients”, Biological Psychiatry 63 (5): 530–3, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.003, PMID 17870056

- ^ Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, Jia P, Assadzadeh A, Flanagan J, Schumacher A, Wang SC, Petronis A (2008), “Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis”, Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82 (3): 696–711, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008, PMC 2427301, PMID 18319075

- ^ a b Falconer DS, D. S. (January 1951), “Two new mutants, ‘trembler’ and ‘reeler’, with neurological actions in the house mouse (Mus musculus L.)”, Journal of Genetics 50 (2): 192–201, doi:10.1007/BF02996215

- ^ Tueting P, Doueiri MS, Guidotti A, Davis JM, Costa E (2006), “Reelin down-regulation in mice and psychosis endophenotypes”, Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30 (8): 1065–77, doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.04.001, PMID 16769115

- ^ Hamburgh M (October 1963), “Analysis of the postnatal developmental effects of "reeler", a neurological mutation in mice. A study in developmental genetics”, Dev. Biol. 19: 165–85, doi:10.1016/0012-1606(63)90040-X, PMID 14069672

- ^ Caviness VS (December 1976), “Patterns of cell and fiber distribution in the neocortex of the reeler mutant mouse”, J. Comp. Neurol. 170 (4): 435–47, doi:10.1002/cne.901700404, PMID 1002868

- ^ Miao GG, Smeyne RJ, D'Arcangelo G, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Morgan JI, Curran T (November 1994), “Isolation of an allele of reeler by insertional mutagenesis”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 (23): 11050–4, doi:10.1073/pnas.91.23.11050, PMC 45164, PMID 7972007

- ^ D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T (April 1995), “A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler”, Nature 374 (6524): 719–23, doi:10.1038/374719a0, PMID 7715726

- ^ Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, et al. (May 1995), “The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons”, Neuron 14 (5): 899–912, doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1, PMID 7748558

- ^ Trommsdorff M, Borg JP, Margolis B, Herz J (December 1998), “Interaction of cytosolic adaptor proteins with neuronal apolipoprotein E receptors and the amyloid precursor protein”, J. Biol. Chem. 273 (50): 33556–60, doi:10.1074/jbc.273.50.33556, PMID 9837937

- ^ Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, et al. (June 1999), “Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2”, Cell 97 (6): 689–701, doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80782-5, PMID 10380922

- ^ Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, et al. (October 1997), “Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice”, Nature 389 (6652): 730–3, doi:10.1038/39601, PMID 9338784

- ^ "Reelin" mentioned in the titles of scientific literature - a search in the Google Scholar

- ^ a b c d e Hossein S. Fatemi, ed. (2008), Reelin Glycoprotein: Structure, Biology and Roles in Health and Disease, Springer, p. 444, ISBN 978-0-387-76760-4

- ^ Lacor PN, Grayson DR, Auta J, Sugaya I, Costa E, Guidotti A (March 2000), “Reelin secretion from glutamatergic neurons in culture is independent from neurotransmitter regulation”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (7): 3556–61, doi:10.1073/pnas.050589597, PMC 16278, PMID 10725375

- ^ Meyer G, Goffinet AM, Fairén A (December 1999), “What is a Cajal-Retzius cell? A reassessment of a classical cell type based on recent observations in the developing neocortex”, Cereb. Cortex 9 (8): 765–75, doi:10.1093/cercor/9.8.765, PMID 10600995

- ^ a b Meyer G, Goffinet AM (July 1998), “Prenatal development of reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the human neocortex”, J. Comp. Neurol. 397 (1): 29–40, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980720)397:1<29::AID-CNE3>3.3.CO;2-7, PMID 9671277

- ^ Schiffmann SN, Bernier B, Goffinet AM (May 1997), “Reelin mRNA expression during mouse brain development”, Eur. J. Neurosci. 9 (5): 1055–71, doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01456.x, PMID 9182958

- ^ Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG, et al. (March 1998), “Reelin is preferentially expressed in neurons synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in cortex and hippocampus of adult rats”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (6): 3221–6, doi:10.1073/pnas.95.6.3221, PMC 19723, PMID 9501244

- ^ Alcántara S, Ruiz M, D'Arcangelo G, et al. (1 October 1998), “Regional and cellular patterns of reelin mRNA expression in the forebrain of the developing and adult mouse”, J. Neurosci. 18 (19): 7779–99, PMID 9742148

- ^ Pesold C, Liu WS, Guidotti A, Costa E, Caruncho HJ (March 1999), “Cortical bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells preferentially express and secrete reelin into perineuronal nets, nonsynaptically modulating gene expression”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (6): 3217–22, doi:10.1073/pnas.96.6.3217, PMC 15922, PMID 10077664

- ^ Suárez-Solá ML, González-Delgado FJ, Pueyo-Morlans M, Medina-Bolívar OC, Hernández-Acosta NC, González-Gómez M, Meyer G (2009), “Neurons in the white matter of the adult human neocortex”, Front Neuroanat 3: 7, doi:10.3389/neuro.05.007.2009, PMC 2697018, PMID 19543540

- ^ Smalheiser NR, Costa E, Guidotti A, et al. (February 2000), “Expression of reelin in adult mammalian blood, liver, pituitary pars intermedia, and adrenal chromaffin cells”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (3): 1281–6, doi:10.1073/pnas.97.3.1281, PMC 15597, PMID 10655522

- ^ Samama B, Boehm N (July 2005), “Reelin immunoreactivity in lymphatics and liver during development and adult life”, Anat Rec a Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 285 (1): 595–9, doi:10.1002/ar.a.20202, PMID 15912522

- ^ a b Kobold D, Grundmann A, Piscaglia F, et al. (May 2002), “Expression of reelin in hepatic stellate cells and during hepatic tissue repair: a novel marker for the differentiation of HSC from other liver myofibroblasts”, J. Hepatol. 36 (5): 607–13, doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00050-8, PMID 11983443

- ^ a b Pulido JS, Sugaya I, Comstock J, Sugaya K (June 2007), “Reelin expression is upregulated following ocular tissue injury”, Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 245 (6): 889–93, doi:10.1007/s00417-006-0458-4, PMID 17120005

- ^ Buchaille R, Couble ML, Magloire H, Bleicher F (September 2000), “A substractive PCR-based cDNA library from human odontoblast cells: identification of novel genes expressed in tooth forming cells”, Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology 19 (5): 421–30, doi:10.1016/S0945-053X(00)00091-3, PMID 10980418

- ^ Allard B, Magloire H, Couble ML, Maurin JC, Bleicher F (September 2006), “Voltage-gated sodium channels confer excitability to human odontoblasts: possible role in tooth pain transmission”, J. Biol. Chem. 281 (39): 29002–10, doi:10.1074/jbc.M601020200, PMID 16831873

- ^ Maurin JC, Couble ML, Didier-Bazes M, Brisson C, Magloire H, Bleicher F (August 2004), “Expression and localization of reelin in human odontoblasts”, Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology 23 (5): 277–85, doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2004.06.005, PMID 15464360

- ^ Yasui N, Nogi T, Kitao T, Nakano Y, Hattori M, Takagi J (June 2007), “Structure of a receptor-binding fragment of reelin and mutational analysis reveal a recognition mechanism similar to endocytic receptors”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (24): 9988–93, doi:10.1073/pnas.0700438104, PMC 1891246, PMID 17548821

- ^ a b Quattrocchi CC, Wannenes F, Persico AM, Ciafré SA, D'Arcangelo G, Farace MG, Keller F. (January 2002), “Reelin is a serine protease of the extracellular matrix”, J. Biol. Chem. 277 (1): 303–9, doi:10.1074/jbc.M106996200, PMID 11689558

- ^ a b Royaux I, Lambert de Rouvroit C, D'Arcangelo G, Demirov D, Goffinet AM (December 1997), “Genomic organization of the mouse reelin gene”, Genomics 46 (2): 240–50, doi:10.1006/geno.1997.4983, PMID 9417911

- ^ Nogi T, Yasui N, Hattori M, Iwasaki K, Takagi J (August 2006), “Structure of a signaling-competent reelin fragment revealed by X-ray crystallography and electron tomography”, EMBO J. 25 (15): 3675–83, doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601240, PMC 1538547, PMID 16858396

- ^ Nakano, Yoshimi; Kohno, Takao; Hibi, Terumasa; Kohno, Shiori; Baba, Atsushi; Mikoshiba, Katsuhiko; Nakajima, Kazunori; Hattori, Mitsuharu (2007-07-13). “The Extremely Conserved C-terminal Region of Reelin Is Not Necessary for Secretion but Is Required for Efficient Activation of Downstream Signaling” (英語). Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (28): 20544–20552. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702300200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 17504759.

- ^ a b Koie, Mari; Okumura, Kyoko; Hisanaga, Arisa; Kamei, Takana; Sasaki, Kazutomo; Deng, Mengyan; Baba, Atsushi; Kohno, Takao et al. (2014-05-02). “Cleavage within Reelin Repeat 3 Regulates the Duration and Range of the Signaling Activity of Reelin Protein” (英語). Journal of Biological Chemistry 289 (18): 12922–12930. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.536326. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 4007479. PMID 24644294.

- ^ Sato, Yoshitaka; Kobayashi, Daichi; Kohno, Takao; Kidani, Yujiro; Prox, Johannes; Becker-Pauly, Christoph; Hattori, Mitsuharu (2015-10-21). “Determination of cleavage site of Reelin between its sixth and seventh repeat and contribution of meprin metalloproteases to the cleavage” (英語). Journal of Biochemistry 159 (3): mvv102. doi:10.1093/jb/mvv102. ISSN 0021-924X.

- ^ Lambert de Rouvroit C, de Bergeyck V, Cortvrindt C, Bar I, Eeckhout Y, Goffinet AM (March 1999), “Reelin, the extracellular matrix protein deficient in reeler mutant mice, is processed by a metalloproteinase”, Exp. Neurol. 156 (1): 214–7, doi:10.1006/exnr.1998.7007, PMID 10192793

- ^ a b Jossin Y, Gui L, Goffinet AM (April 2007), “Processing of Reelin by embryonic neurons is important for function in tissue but not in dissociated cultured neurons”, J. Neurosci. 27 (16): 4243–52, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0023-07.2007, PMID 17442808

- ^ Ogino, Himari; Hisanaga, Arisa; Kohno, Takao; Kondo, Yuta; Okumura, Kyoko; Kamei, Takana; Sato, Tempei; Asahara, Hiroshi et al. (2017-03-22). “Secreted Metalloproteinase ADAMTS-3 Inactivates Reelin” (英語). Journal of Neuroscience 37 (12): 3181–3191. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3632-16.2017. ISSN 0270-6474. PMID 28213441.

- ^ a b Blake SM, Strasser V, Andrade N, et al. (October 2008), “Thrombospondin-1 binds to ApoER2 and VLDL receptor and functions in postnatal neuronal migration”, EMBO J. 27 (22): 3069–80, doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.223, PMC 2585172, PMID 18946489

- ^ Lennington JB, Yang Z, Conover JC (November 2003), “Neural stem cells and the regulation of adult neurogenesis”, Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 1: 99, doi:10.1186/1477-7827-1-99, PMC 293430, PMID 14614786

- ^ a b c d Nomura T, Takahashi M, Hara Y, Osumi N (2008), “Patterns of neurogenesis and amplitude of Reelin expression are essential for making a mammalian-type cortex”, PLoS ONE 3 (1): e1454, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001454, PMC 2175532, PMID 18197264

- ^ a b Hartfuss E, Förster E, Bock HH, et al. (October 2003), “Reelin signaling directly affects radial glia morphology and biochemical maturation”, Development 130 (19): 4597–609, doi:10.1242/dev.00654, PMID 12925587

- ^ Del R�o JA, Heimrich B, Borrell V, F�rster E, Drakew A, Alc�ntara S, Nakajima K, Miyata T et al. (January 1997), “A role for Cajal-Retzius cells and reelin in the development of hippocampal connections.”, Nature 385 (6611): 70–4, doi:10.1038/385070a0, PMID 8985248

- ^ Borrell V, Del R�o JA, Alc�ntara S, Derer M, Mart�nez A, D'arcangelo G, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K et al. (February 1999), “Reelin regulates the development and synaptogenesis of the layer-specific entorhino-hippocampal connections.”, The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 19 (4): 1345–58, PMID 9952412

- ^ a b Hack I, Bancila M, Loulier K, Carroll P, Cremer H (October 2002), “Reelin is a detachment signal in tangential chain-migration during postnatal neurogenesis”, Nat. Neurosci. 5 (10): 939–45, doi:10.1038/nn923, PMID 12244323

- ^ a b c d Yoshida M, Assimacopoulos S, Jones KR, Grove EA (February 2006), “Massive loss of Cajal-Retzius cells does not disrupt neocortical layer order”, Development 133 (3): 537–45, doi:10.1242/dev.02209, PMID 16410414

- ^ Yip YP, Mehta N, Magdaleno S, Curran T, Yip JW (March 2009), “Ectopic expression of reelin alters migration of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord”, J. Comp. Neurol. 515 (2): 260–268, doi:10.1002/cne.22044, PMID 19412957

- ^ a b Campo CG, Sinagra M, Verrier D, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P (2009), “Reelin secreted by GABAergic neurons regulates glutamate receptor homeostasis”, PLoS ONE 4 (5): e5505, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005505, PMC 2675077, PMID 19430527

- ^ Andrade N, Komnenovic V, Blake SM, et al. (May 2007), “ApoER2/VLDL receptor and Dab1 in the rostral migratory stream function in postnatal neuronal migration independently of Reelin”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (20): 8508–13, doi:10.1073/pnas.0611391104, PMC 1895980, PMID 17494763

- ^ Frotscher M, Haas CA, Förster E (June 2003), “Reelin controls granule cell migration in the dentate gyrus by acting on the radial glial scaffold”, Cereb. Cortex 13 (6): 634–40, doi:10.1093/cercor/13.6.634, PMID 12764039

- ^ INSERM - Olivier Manzoni - Physiopathology of Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity Archived 2006年11月25日, at the Wayback Machine. - Bordo neuroscience institute.

- ^ Sinagra M, Verrier D, Frankova D, Korwek KM, Blahos J, Weeber EJ, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P (June 2005), “Reelin, very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 control somatic NMDA receptor composition during hippocampal maturation in vitro”, J. Neurosci. 25 (26): 6127–36, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1757-05.2005, PMID 15987942

- ^ Groc L, Choquet D, Stephenson FA, Verrier D, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P (2007), “NMDA receptor surface trafficking and synaptic subunit composition are developmentally regulated by the extracellular matrix protein Reelin”, J. Neurosci. 27 (38): 10165–75, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1772-07.2007, PMID 17881522

- ^ Liu XB, Murray KD, Jones EG (October 2004), “Switching of NMDA receptor 2A and 2B subunits at thalamic and cortical synapses during early postnatal development”, J. Neurosci. 24 (40): 8885–95, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2476-04.2004, PMID 15470155

- ^ Bar I, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM (December 2000), “The evolution of cortical development. An hypothesis based on the role of the Reelin signaling pathway”, Trends Neurosci. 23 (12): 633–8, doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01675-1, PMID 11137154

- ^ Molnár Z, Métin C, Stoykova A, et al. (February 2006), “Comparative aspects of cerebral cortical development”, Eur. J. Neurosci. 23 (4): 921–34, doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04611.x, PMC 1931431, PMID 16519657

- ^ a b Pérez-García CG, González-Delgado FJ, Suárez-Solá ML, et al. (January 2001), “Reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the adult vertebrate pallium”, J. Chem. Neuroanat. 21 (1): 41–51, doi:10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00104-6, PMID 11173219

- ^ Costagli A, Kapsimali M, Wilson SW, Mione M (August 2002), “Conserved and divergent patterns of Reelin expression in the zebrafish central nervous system”, J. Comp. Neurol. 450 (1): 73–93, doi:10.1002/cne.10292, PMID 12124768

- ^ Goffinet AM (2006), “What makes us human? A biased view from the perspective of comparative embryology and mouse genetics”, J Biomed Discov Collab 1: 16, doi:10.1186/1747-5333-1-13, PMC 1769396, PMID 17132178

- ^ Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, et al. (September 2006), “An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans”, Nature 443 (7108): 167–72, doi:10.1038/nature05113, PMID 16915236

- ^ Williamson SH, Hubisz MJ, Clark AG, Payseur BA, Bustamante CD, Nielsen R (2007), “Localizing Recent Adaptive Evolution in the Human Genome”, PLoS Genetics 3 (6): e90, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030090, PMC 1885279, PMID 17542651

- ^ Wade N (2007年6月26日). “Humans Have Spread Globally, and Evolved Locally”. Science (New York Times) 2008年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b Zhang G, Assadi AH, McNeil RS, Beffert U, Wynshaw-Boris A, Herz J, Clark GD, D’Arcangelo G. (2007), “The Pafah1b complex interacts with the Reelin receptor VLDLR”, PLoS ONE 2 (2): e252, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000252, PMC 1800349, PMID 17330141

- ^ Schmid RS, Jo R, Shelton S, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES (October 2005), “Reelin, integrin and DAB1 interactions during embryonic cerebral cortical development”, Cereb. Cortex 15 (10): 1632–6, doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi041, PMID 15703255

- ^ Senzaki K, Ogawa M, Yagi T (December 1999), “Proteins of the CNR family are multiple receptors for Reelin”, Cell 99 (6): 635–47, doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81552-4, PMID 10612399

- ^ a b Jossin Y, Ignatova N, Hiesberger T, Herz J, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM (January 2004), “The central fragment of Reelin, generated by proteolytic processing in vivo, is critical to its function during cortical plate development”, J. Neurosci. 24 (2): 514–21, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-03.2004, PMID 14724251

- ^ Belvindrah R, Graus-Porta D, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Müller U (December 2007), “Beta1 integrins in radial glia but not in migrating neurons are essential for the formation of cell layers in the cerebral cortex”, J. Neurosci. 27 (50): 13854–65, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4494-07.2007, PMID 18077697

- ^ Howell BW, Gertler FB, Cooper JA (January 1997), “Mouse disabled (mDab1): a Src binding protein implicated in neuronal development”, EMBO J. 16 (1): 121–32, doi:10.1093/emboj/16.1.121, PMC 1169619, PMID 9009273

- ^ Arnaud L, Ballif BA, Förster E, Cooper JA (January 2003), “Fyn tyrosine kinase is a critical regulator of disabled-1 during brain development”, Curr. Biol. 13 (1): 9–17, doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01397-0, PMID 12526739

- ^ Feng L, Allen NS, Simo S, Cooper JA (November 2007), “Cullin 5 regulates Dab1 protein levels and neuron positioning during cortical development”, Genes Dev. 21 (21): 2717–30, doi:10.1101/gad.1604207, PMC 2045127, PMID 17974915

- ^ Kerjan G, Gleeson JG (November 2007), “A missed exit: Reelin sets in motion Dab1 polyubiquitination to put the break on neuronal migration”, Genes Dev. 21 (22): 2850–4, doi:10.1101/gad.1622907, PMID 18006681

- ^ a b c Keilani S, Sugaya K (July 2008), “Reelin induces a radial glial phenotype in human neural progenitor cells by activation of Notch-1”, BMC Dev. Biol. 8 (1): 69, doi:10.1186/1471-213X-8-69, PMC 2447831, PMID 18593473

- ^ Hack I, Hellwig S, Junghans D, Brunne B, Bock HH, Zhao S, Frotscher M (2007), “Divergent roles of ApoER2 and Vldlr in the migration of cortical neurons”, Development 134 (21): 3883–91, doi:10.1242/dev.005447, PMID 17913789

- ^ Utsunomiya-Tate N, Kubo K, Tate S, et al. (August 2000), “Reelin molecules assemble together to form a large protein complex, which is inhibited by the function-blocking CR-50 antibody”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (17): 9729–34, doi:10.1073/pnas.160272497, PMC 16933, PMID 10920200

- ^ Kubo K, Mikoshiba K, Nakajima K (August 2002), “Secreted Reelin molecules form homodimers”, Neurosci. Res. 43 (4): 381–8, doi:10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00068-8, PMID 12135781

- ^ a b Strasser V, Fasching D, Hauser C, et al. (February 2004), “Receptor clustering is involved in Reelin signaling”, Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 (3): 1378–86, doi:10.1128/MCB.24.3.1378-1386.2004, PMC 321426, PMID 14729980

- ^ Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Durudas A, et al. (August 2005), “Modulation of synaptic plasticity and memory by Reelin involves differential splicing of the lipoprotein receptor Apoer2” (PDF), Neuron 47 (4): 567–79, doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.007, PMID 16102539

- ^ Miller CA, Sweatt JD (March 2007), “Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation”, Neuron 53 (6): 857–69, doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022, PMID 17359920

- ^ Matsuki T, Pramatarova A, Howell BW (May 2008), “Reduction of Crk and CrkL expression blocks reelin-induced dendritogenesis”, J. Cell. Sci. 121 (Pt 11): 1869–75, doi:10.1242/jcs.027334, PMC 2430739, PMID 18477607

- ^ Ballif BA, Arnaud L, Arthur WT, Guris D, Imamoto A, Cooper JA (April 2004), “Activation of a Dab1/CrkL/C3G/Rap1 pathway in Reelin-stimulated neurons”, Curr. Biol. 14 (7): 606–10, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.038, PMID 15062102

- ^ Park TJ, Curran T (December 2008), “Crk and crk-like play essential overlapping roles downstream of disabled-1 in the reelin pathway”, J. Neurosci. 28 (50): 13551–62, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-08.2008, PMC 2628718, PMID 19074029

- ^ Lugli G, Krueger JM, Davis JM, Persico AM, Keller F, Smalheiser NR (September 2003), “Methodological factors influencing measurement and processing of plasma reelin in humans”, BMC Biochem. 4: 9, doi:10.1186/1471-2091-4-9, PMC 200967, PMID 12959647

- ^ Hibi T, Hattori M (March 2009), “The N-terminal fragment of Reelin is generated after endocytosis and released through the pathway regulated by Rab11”, FEBS Lett. 583 (8): 1299–303, doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.024, PMID 19303411

- ^ Chameau P, Inta D, Vitalis T, Monyer H, Wadman WJ, van Hooft JA (April 2009), “The N-terminal region of reelin regulates postnatal dendritic maturation of cortical pyramidal neurons”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (17): 7227–32, doi:10.1073/pnas.0810764106, PMC 2678467, PMID 19366679

- ^ Chai X, Förster E, Zhao S, Bock HH, Frotscher M (January 2009), “Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3”, J. Neurosci. 29 (1): 288–99, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2934-08.2009, PMID 19129405

- ^ Frotscher M, Chai X, Bock HH, Haas CA, Förster E, Zhao S (April 2009), “Role of Reelin in the development and maintenance of cortical lamination”, J. Neural. Transm. 116 (11): 1451–5, doi:10.1007/s00702-009-0228-7, PMID 19396394

- ^ Arnaud L, Ballif BA, Cooper JA (December 2003), “Regulation of protein tyrosine kinase signaling by substrate degradation during brain development”, Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (24): 9293–302, doi:10.1128/MCB.23.24.9293-9302.2003, PMC 309695, PMID 14645539

- ^ Ohshima T, Suzuki H, Morimura T, Ogawa M, Mikoshiba K (April 2007), “Modulation of Reelin signaling by Cyclin-dependent kinase 5”, Brain Res. 1140: 84–95, doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.121, PMID 16529723

- ^ Keshvara L, Magdaleno S, Benhayon D, Curran T (June 2002), “Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates disabled 1 independently of Reelin signaling”, J. Neurosci. 22 (12): 4869–77, PMID 12077184

- ^ Kobayashi S, Ishiguro K, Omori A, Takamatsu M, Arioka M, Imahori K, Uchida T (December 1993), “A cdc2-related kinase PSSALRE/cdk5 is homologous with the 30 kDa subunit of tau protein kinase II, a proline-directed protein kinase associated with microtubule”, FEBS Lett. 335 (2): 171–5, doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)80723-8, PMID 8253190

- ^ Beffert U, Morfini G, Bock HH, Reyna H, Brady ST, Herz J (December 2002), “Reelin-mediated signaling locally regulates protein kinase B/Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta”, J. Biol. Chem. 277 (51): 49958–64, doi:10.1074/jbc.M209205200, PMID 12376533

- ^ Sasaki S, Shionoya A, Ishida M, Gambello MJ, Yingling J, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hirotsune S (December 2000), “A LIS1/NUDEL/cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain complex in the developing and adult nervous system”, Neuron 28 (3): 681–96, doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00146-X, PMID 11163259

- ^ a b Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Morfini G, Ko J, Brady ST, Tsai LH, Sweatt JD, Herz J (February 2004), “Reelin and cyclin-dependent kinase 5-dependent signals cooperate in regulating neuronal migration and synaptic transmission”, J. Neurosci. 24 (8): 1897–906, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4084-03.2004, PMID 14985430

- ^ Ohshima T, Ogawa M, Veeranna, Hirasawa M, Longenecker G, Ishiguro K, Pant HC, Brady RO, Kulkarni AB, Mikoshiba K (February 2001), “Synergistic contributions of cyclin-dependant kinase 5/p35 and Reelin/Dab1 to the positioning of cortical neurons in the developing mouse brain”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (5): 2764–9, doi:10.1073/pnas.051628498, PMC 30213, PMID 11226314

- ^ Hong SE, Shugart YY, Huang DT, et al. (September 2000), “Autosomal recessive lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia is associated with human RELN mutations”, Nat. Genet. 26 (1): 93–6, doi:10.1038/79246, PMID 10973257

- ^ Crino P (November 2001), “New RELN Mutation Associated with Lissencephaly and Epilepsy”, Epilepsy Curr. 1 (2): 72, doi:10.1046/j.1535-7597.2001.00017.x, PMC 320825, PMID 15309195

- ^ Impagnatiello F, Guidotti AR, Pesold C, et al. (December 1998), “A decrease of reelin expression as a putative vulnerability factor in schizophrenia”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (26): 15718–23, doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15718, PMC 28110, PMID 9861036

- ^ a b Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, et al. (November 2000), “Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study”, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57 (11): 1061–9, doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061, PMID 11074872

- ^ Fatemi SH, Earle JA, McMenomy T (November 2000), “Reduction in Reelin immunoreactivity in hippocampus of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression”, Mol. Psychiatry 5 (6): 654–63, 571, doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000783, PMID 11126396

- ^ a b Fatemi SH, Hossein Fatemi S, Stary JM, Earle JA, Araghi-Niknam M, Eagan E (January 2005), “GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders as reflected by decreased levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa and Reelin proteins in cerebellum”, Schizophr. Res. 72 (2-3): 109–22, doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.017, PMID 15560956

- ^ a b Veldic M, Kadriu B, Maloku E, Agis-Balboa RC, Guidotti A, Davis JM, Costa E (March 2007), “Epigenetic mechanisms expressed in basal ganglia GABAergic neurons differentiate schizophrenia from bipolar disorder”, Schizophr. Res. 91 (1-3): 51–61, doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.029, PMC 1876737, PMID 17270400

- ^ Eastwood SL, Harrison PJ (September 2003), “Interstitial white matter neurons express less reelin and are abnormally distributed in schizophrenia: towards an integration of molecular and morphologic aspects of the neurodevelopmental hypothesis”, Mol. Psychiatry 8 (9): 769, 821–31, doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001371, PMID 12931209

- ^ Abdolmaleky HM, Cheng KH, Russo A, et al. (April 2005), “Hypermethylation of the reelin (RELN) promoter in the brain of schizophrenic patients: a preliminary report”, Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 134B (1): 60–6, doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30140, PMID 15717292

- ^ Fatemi SH, Kroll JL, Stary JM (October 2001), “Altered levels of Reelin and its isoforms in schizophrenia and mood disorders”, Neuroreport 12 (15): 3209–15, doi:10.1097/00001756-200110290-00014, PMID 11711858

- ^ Knable MB, Torrey EF, Webster MJ, Bartko JJ (July 2001), “Multivariate analysis of prefrontal cortical data from the Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortium”, Brain Res. Bull. 55 (5): 651–9, doi:10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00521-4, PMID 11576762

- ^ Persico AM, D'Agruma L, Maiorano N, Totaro A, Militerni R, Bravaccio C, Wassink TH, Schneider C, Melmed R, Trillo S, Montecchi F, Palermo M, Pascucci T, Puglisi-Allegra S, Reichelt KL, Conciatori M, Marino R, Quattrocchi CC, Baldi A, Zelante L, Gasparini P, Keller F (March 2001), “Reelin gene alleles and haplotypes as a factor predisposing to autistic disorder”, Mol. Psychiatry 6 (2): 150–9, doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000850, PMID 11317216

- ^ Haas CA, Dudeck O, Kirsch M, et al. (July 2002), “Role for reelin in the development of granule cell dispersion in temporal lobe epilepsy”, J. Neurosci. 22 (14): 5797–802, PMID 12122039

- ^ Heinrich C, Nitta N, Flubacher A, et al. (April 2006), “Reelin deficiency and displacement of mature neurons, but not neurogenesis, underlie the formation of granule cell dispersion in the epileptic hippocampus”, J. Neurosci. 26 (17): 4701–13, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5516-05.2006, PMID 16641251

- ^ Kobow K, Jeske I, Hildebrandt M, Hauke J, Hahnen E, Buslei R, Buchfelder M, Weigel D, Stefan H, Kasper B, Pauli E, Blümcke I (March 2009), “Increased Reelin Promoter Methylation Is Associated With Granule Cell Dispersion in Human Temporal Lobe Epilepsy”, J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68 (4): 356–64, doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31819ba737, PMID 19287316

- ^ a b Herz J, Beffert U (October 2000), “Apolipoprotein E receptors: linking brain development and Alzheimer's disease”, Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1 (1): 51–8, doi:10.1038/35036221, PMID 11252768

- ^ Herz J, Chen Y (November 2006), “Reelin, lipoprotein receptors and synaptic plasticity”, Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7 (11): 850–9, doi:10.1038/nrn2009, PMID 17053810

- ^ Sato N, Fukushima N, Chang R, Matsubayashi H, Goggins M (February 2006), “Differential and epigenetic gene expression profiling identifies frequent disruption of the RELN pathway in pancreatic cancers.”, Gastroenterology 130 (2): 548–65, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.008, PMID 16472607

- ^ Perrone G, Vincenzi B, Zagami M, Santini D, Panteri R, Flammia G, Verzi A, Lepanto D, Morini S, Russo A, Bazan V, Tomasino RM, Morello V, Tonini G, Rabitti C. (2007) Reelin expression in human prostate cancer: a marker of tumor aggressiveness based on correlation with grade. Modern Pathology. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800743. PMID 17277764

- ^ Seigel GM, Hackam AS, Ganguly A, Mandell LM, Gonzalez-Fernandez F (2007), “Human embryonic and neuronal stem cell markers in retinoblastoma”, Mol. Vis. 13: 823–32, PMC 2768758, PMID 17615543

- ^ Schrauwen I, Ealy M, Huentelman MJ, Thys M, Homer N, Vanderstraeten K, Fransen E, Corneveaux JJ, Craig DW, Claustres M, Cremers CW, Dhooge I, Van de Heyning P, Vincent R, Offeciers E, Smith RJ, Van Camp G (February 2009), “A Genome-wide Analysis Identifies Genetic Variants in the RELN Gene Associated with Otosclerosis”, Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84 (3): 328–38, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.023, PMC 2667982, PMID 19230858

- ^ a b Smit-Rigter LA, Champagne DL, van Hooft JA (2009), “Lifelong impact of variations in maternal care on dendritic structure and function of cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in rat offspring”, PLoS ONE 4 (4): e5167, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005167, PMC 2663818, PMID 19357777

- ^ Wang GS, Hong CJ, Yen TY, Huang HY, Ou Y, Huang TN, Jung WG, Kuo TY, Sheng M, Wang TF, Hsueh YP (April 2004), “Transcriptional modification by a CASK-interacting nucleosome assembly protein”, Neuron 42 (1): 113–28, doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00139-4, PMID 15066269

- ^ Weaver IC, Meaney MJ, Szyf M (February 2006), “Maternal care effects on the hippocampal transcriptome and anxiety-mediated behaviors in the offspring that are reversible in adulthood”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (9): 3480–5, doi:10.1073/pnas.0507526103, PMC 1413873, PMID 16484373

- ^ a b Lussier AL, Caruncho HJ, Kalynchuk LE (May 2009), “Repeated exposure to corticosterone, but not restraint, decreases the number of reelin-positive cells in the adult rat hippocampus”, Neurosci. Lett. 460 (2): 170–4, doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.050, PMID 19477232

- ^ Dong E, Nelson M, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A (August 2008), “Clozapine and sulpiride but not haloperidol or olanzapine activate brain DNA demethylation”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (36): 13614–9, doi:10.1073/pnas.0805493105, PMC 2533238, PMID 18757738

- ^ Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD (April 2009), “Chronic psychotropic drug treatment causes differential expression of Reelin signaling system in frontal cortex of rats”, Schizophr. Res. 111 (1-3): 138–52, doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.002, PMID 19359144

- ^ Hiesberger T, Trommsdorff M, Howell BW, Goffinet A, Mumby MC, Cooper JA, Herz J (October 1999), “Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation”, Neuron 24 (2): 481–9, doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80861-2, PMID 10571241

- ^ D'Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T (October 1999), “Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors”, Neuron 24 (2): 471–9, doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80860-0, PMID 10571240

- ^ Andersen, Olav M; Benhayon David, Curran Tom, Willnow Thomas E (Aug. 2003), “Differential binding of ligands to the apolipoprotein E receptor 2”, Biochemistry (United States) 42 (31): 9355–64, doi:10.1021/bi034475p, ISSN 0006-2960, PMID 12899622

- ^ Benhayon, David; Magdaleno Susan, Curran Tom (Apr. 2003), “Binding of purified Reelin to ApoER2 and VLDLR mediates tyrosine phosphorylation of Disabled-1”, Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. (Netherlands) 112 (1-2): 33–45, doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00032-9, ISSN 0169-328X, PMID 12670700

参考文献[編集]

- The book: Fatemi, S. Hossein (2008), Reelin Glycoprotein: Structure, Biology and Roles in Health and Disease, Berlin: Springer, pp. 444 pages, ISBN 978-0-387-76760-4

- A review: Förster E, Jossin Y, Zhao S, Chai X, Frotscher M, Goffinet AM (February 2006), “Recent progress in understanding the role of Reelin in radial neuronal migration, with specific emphasis on the dentate gyrus”, Eur. J. Neurosci. 23 (4): 901–9, doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04612.x, PMID 16519655

外部リンク[編集]

論文、出版物[編集]

- “Gabriella D'Arcangelo”. Rutgers University. 2008年8月23日閲覧。 “the scientist who discovered the reelin gene and protein”

- Human RELN at WikiGenes

図や写真[編集]

- “Reelin gene expression in mice”. Brain Gene Expression Map. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. 2008年8月23日閲覧。

- “Schematic representation of signaling through the LDLR family members apoER2 and VLDL receptor”. 2008年8月23日閲覧。 – A figure from Beffert U, Stolt PC, Herz J (March 2004), “Functions of lipoprotein receptors in neurons”, J. Lipid Res. 45 (3): 403–9, doi:10.1194/jlr.R300017-JLR200, PMID 14657206

- “Proposed mechanism by which mouse RELN promoter regulate reelin gene expression”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008年8月23日閲覧。 – A figure from Dong E, Agis-Balboa RC, Simonini MV, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A (August 2005), “Reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 promoter remodeling in an epigenetic methionine-induced mouse model of schizophrenia”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (35): 12578–83, doi:10.1073/pnas.0505394102, PMC 1194936, PMID 16113080

- “Corticogenesis in wild-type, reeler mutant and β1 deficient mice”. 2008年8月23日閲覧。 “Pictorial rendition of the difference that the lack of reelin brings to the cortical structure” – A figure from Magdaleno SM, Curran T (December 2001), “Brain development: integrins and the Reelin pathway”, Curr. Biol. 11 (24): R1032–5, doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00618-2, PMID 11747842

- “Effects of human and naturally occurring mouse RELN mutations on the predicted protein.”. Nature Genetics. 2008年8月23日閲覧。 A figure from Hong SE, Shugart YY, Huang DT, et al. (September 2000), “Autosomal recessive lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia is associated with human RELN mutations”, Nat. Genet. 26 (1): 93–6, doi:10.1038/79246, PMID 10973257

- “MRI analysis of chromosome 7q22-linked lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia.”. Nature Genetics. 2008年8月23日閲覧。 – A figure from Hong et al.