「クロストリジウム・ディフィシル腸炎」の版間の差分

en:Clostridium difficile colitis(2016年7月6日 水曜日 4:30:39(UTC))を翻訳。→Notable outbreaks: 節は省略しました。 |

(相違点なし)

|

2016年7月9日 (土) 06:19時点における版

| クロストリジウム・ディフィシル腸炎、偽膜性大腸炎 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 血液寒天培地中のC. difficile コロニー | |

| 概要 | |

| 診療科 | Infectious disease |

| 分類および外部参照情報 | |

| ICD-10 | A04.7 |

| ICD-9-CM | 008.45 |

| MedlinePlus | 000259 |

| eMedicine | med/1942 |

| MeSH | D004761 |

クロストリジウム・ディフィシル腸炎(Clostridium difficile colitis)又は偽膜性大腸炎(Pseudomembranous colitis)とは、芽胞産生性偏性嫌気性細菌であるクロストリジウム・ディフィシル(Clostridium difficile )の異常増殖の結果として生じる大腸炎である[1]。クロストリジウム・ディフィシル関連下痢症(C. difficile associated diarrhea、CDAD)と呼ばれる炎症性下痢症の原因となる。 潜在性のC. difficile 感染症(CDI)は屢々インフルエンザ様症状と共通点が有り、炎症性腸疾患患者の場合には腸炎の再燃を思わせる.[2]。C. difficile が産生する毒素は腹痛を伴う膨満感や下痢を引き起こし、重篤となる場合も有る。

この大腸炎は、抗生物質の投与等で正常な腸内細菌叢が撹乱されて菌交代症が生ずる事で発生すると考えられている。正常腸内細菌叢を掻き乱す事は、C. difficile に増殖の機会を与えている事になる[3]。この疾患は抗生物質関連下痢の一つである。

治療法は、非重篤なCDIの場合は屢々、抗生物質を中止するのみである。重篤な場合には、C. difficile に対する抗生物質が投与される。最大で2割の患者で、CDIの再燃が発生する[4]。2011年に米国では29,000名の患者がC. difficile 感染症で亡くなった[5]。

「クロストリジウム」はギリシア語で「紡錘」を意味するkloster (κλωστήρ)[6]から、「ディフィシル」はラテン語で「困難」を意味するdifficile [7]から[注 1]命名された。

徴候と症状

CDIの徴候と症状は軽度な下痢から時に致死的な大腸炎までが含まれる[9]。

成人の場合は、臨床予測ルールに採用される最良の臨床症状は抗生物質暴露後の著明な下痢(24時間以内に3回以上の軟便又は水様便)、腹痛、発熱(40.5℃迄)、並びに馬糞に似た特有の糞臭である[10]。入院患者の場合は、「抗生物質投与後の下痢及び腹痛」は感度86%、特異度45%であった[11]。この研究では、細胞毒素検出率は14%であり、陽性適中率は18%、陰性適中率は94%であった。

小児の場合は、最適なCDI検出症状は、「1日3回以上の便通が2日以上継続した後の水性下痢」であり「発熱有り、食欲無し、嘔気及び/又は腹痛有り」であった[1]。しかし、これらの感染症では重篤な大腸炎を起こしていても下痢が殆ど又は全く無い場合も有る。

原因

C. difficile菌への顕性感染は、C. difficile 下痢の原因である。

C. difficile

クロストリジウム属は偏性嫌気性運動性細菌であり、自然界に広く分布し、特に土壌中に豊富に存在する。

顕微鏡下では、桿状で一端に特徴的な(ドラムスティック又は紡錘状と表現される)細胞が付着している[訳語疑問点]。C. difficile はグラム染色陽性で、酸素不在下でヒト体温の寒天培地上で最適成長する。ストレスを与えると芽胞を形成して休眠し、栄養型では生存出来ない極端な環境でも生き延びる事が可能である[4]。

C. difficile はヒト大腸内に存在しており、成人の2〜5%で検出される[4]。

病原性C. difficile 株は複数の毒素を産生する[12]。その性質が最も良く判っている毒素はエンテロトキシン(腸毒素、Clostridium difficile toxin A)とサイトトキシン(細胞毒素、Clostridium difficile toxin B)である。両者は感染患者に下痢及び炎症を発生させるが、その寄与の大きさについては議論がなされている[4]。トキシンAおよびトキシンBは、RhoファミリーG蛋白質をターゲットとして不活性化させるグルコース転移酵素である。トキシンBは低分子量GTP結合Rho蛋白質のADPリボース化の減少と関連するメカニズムでアクチンの脱重合を誘導する[13]。もう1つのトキシンである二元毒素も産生される事が知られているが、疾患に於ける役割は充分には解明されていない[14]。

CDIに対する抗生物質治療はC. difficile の薬剤耐性と細菌学的特性(芽胞形成、偽膜生成)から困難である[4]。シプロフロキサシンやレボフロキサシン等のニューキノロン系抗生物質に耐性であるC. difficile の新型高毒性株が北米大陸で地理的に分散して集団感染を起こしたと2005年に報告された[15]。アトランタの米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)は、新型流行株について毒性の上昇、抗生物質への耐性、或いはその両方について警告を発した[16]。

C. difficile は糞口経路でヒトからヒトへと感染する。この微生物は熱等に耐性を持つ芽胞を形成し、アルコール系の手指消毒液やルーチンに行われる清浄化では殺菌されない。芽胞は臨床環境下で長時間生存する。その為、C. difficile は殆ど全ての物の表面から検出され得る。一旦芽胞が体内に取り込まれると、芽胞の耐酸性に因り無傷で胃を通過する。胆汁酸に触れると、C. difficile は“発芽”して栄養型となり、大腸内で増殖を開始する。

2005年中に、C. difficile 強毒株が、制限酵素処理解析でBI型、パルスフィールド電気泳動で北米NAP1型、リボタイピングで027型である事が判明した。その為この菌株はC. difficile BI/NAP1/027と呼ばれている[17]。

リスク因子

抗生物質

C. difficile 腸炎の発生は、抗生物質であるニューキノロン、セファロスポリン、クリンダマイシンの使用と強く相関している[18]。

一部の研究者は、日常的な家畜への抗生物質使用がC. difficile 等の流行に結び付く危険性が有ると指摘している[19]。

ヘルスケア環境

感染は殆どの場合、病院や介護老人福祉施設等の医療関連施設で発生しているが、これらの施設外での感染も増加している。C. difficile の推定保有率は2週間以内の入院の場合は13%、4週間以上の入院の場合は50%と見積もられている[20]。

長期入院している場合や介護施設に入居している場合は、1年以上の入院・入居は菌定着の独立リスク因子である[21]。

胃酸抑制療法

市中CDIの増加率は、胃酸抑制薬の使用に相関している。ヒスタミンH2受容体拮抗薬の使用で感染症のリスクは1.5倍に、プロトンポンプ阻害薬の1日1回の使用で1.7倍に、それを超える頻度での使用で2.4倍に増加する[22][23]。

病態生理学

あらゆるペニシリン系抗生物質(アンピシリン等)、セファロスポリン、クリンダマイシン等の抗生物質(前掲に限らない)を全身投与すると、正常な腸内細菌叢が変化する。特に、抗生物質が一部の微生物を殺してしまうと、生き残った競合細菌は、繁殖場所及び栄養の点で競争が少なくなり、抗生物質使用前よりも広い場所で旺盛に繁殖する。Clostridium difficile はその様な微生物の一つである。腸内での繁殖に加えて、C. difficile は毒素を産生する。トキシンAとトキシンBを生産しなければ、C. difficile は偽膜性大腸炎を引き起こす可能性は低いと思われる[24]。重症感染症に関連した大腸炎は炎症反応の一部であり、偽膜は、炎症細胞、フィブリン、壊死細胞から成る粘稠な集合体である[4]。

診断

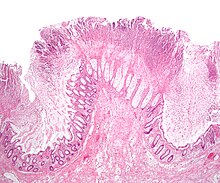

C. difficile 毒素を検出する臨床検査が登場する以前は、大腸内視鏡検査やS状結腸鏡検査が盛んに行われていた。大腸や直腸での「偽膜」形成はクロストリジウム・ディフィシル腸炎を強く示唆するものであったが、確定診断出来るものではなかった[25]。偽膜は炎症性のデブリや白血球から構成されており、C. difficile 特異的ではない為、C. difficile 毒素を検出する検査が最初に実施される様になったが、内視鏡検査は今でも実施されている。毒素検査ではトキシンAとトキシンBのみが検査されるが、C. difficile は他の毒素も産生する。検査は100%正確ではなく、偽陰性は稀ではあるが、繰り返し検査したとしても完全に排除する事は出来ない。

サイトトキシン検査

C. difficile 毒素は培養細胞塊に対しては細胞変性効果を示し、特異的な抗血清で見られる中和効果は、新たなCDI診断技術を開発する際に最も標準的な比較対象となっている[4]。長い時間と多くの手間が掛かるが、選択性培地で毒素産生コロニーを発生させ毒素の産生を確かめる方法は検査のゴールドスタンダードであり、感度特異度共に最高である[26]。

トキシンELISA

トキシンAとトキシンBの酵素結合免疫吸着検査法(ELISA)は、感度63〜99%、特異度93〜100%である。

以前は、1回の下痢症状発生中に糞便サンプルを最大3回採取して検査する事で除外診断出来るとされていたが、今ではその方法では不充分であるとされている[27]。C. difficile 毒素は治療が有効であれば一掃される。多くの病院では、産生される事の多いトキシンAのみが検査されている。トキシンBのみを産生する株が多くの病院から見つかっており、A、Bの両毒素を検査すべきである[28][29]。最初に両毒素を検査しない事は臨床検査の結果確定を遅らせ、屢々疾患を遷延させ、予後不良を来たす。

その他の糞便検査

糞便中の白血球量やラクトフェリン濃度が検査法として提案された事が有るが、何方も正確性に限界がある[30]。

PCR

糞便資料をリアルタイムPCRで分析すると、検出率90%程度、偽陽性4%程度で検査する事が出来る[31]。マルチステップPCR検査アルゴリズムで全般的なパフォーマンスを改善出来る。

予防

抗生物質

最も効果的なCDI予防法は、抗生物質の使用適正化である。CDIが多い病院内では、CDIを発症した殆どの全ての患者で抗生物質が使用されていた。抗生物質の適正使用は容易であるにも拘わらず、約半数の抗生物質使用は不適切なものであった。この事は、病院の他、診療所、市中、大学内にも当て嵌まる。不要な抗生物質の使用を制限してCDIが減少する(集団感染か否かに拘らず)事は、明確に示されている。2011年には、CDI感染症は米国の病院内で見られた医薬品の副作用の内で最多であった[32]。

共生細菌

プロバイオティクスが感染予防や再発防止に有用であるとの報告が有る[33][34]。C. difficile に対する免疫が抑制されていない患者に対してもSaccharomyces boulardii を用いた治療は有用であった[35][36]。米国感染症学会は2010年には、合併症の危険が有るとしてS. boulardii の使用に反対した[33][35]。しかしその後のレビューでは、治療に伴う有害事象の増加は認められず[34]、治療は全般的に安全であると思われた[37]。

感染制御

微生物伝播を最小限にする為には、厳密な感染(制御)プロトコルが必要である[38]。手袋を着ける、重要性の低い医療用具はCDI感染患者1人にのみ使用して使い捨てる、等の感染制御手順は、予防に効果的である[39]。これは病院内でのC. difficile 拡散を制限出来る。加えて、石鹸及び水で手を洗うと汚染された手指から芽胞を除去する事が出来るが、アルコール消毒液で手を擦る方法では効果がない[40]。

0.55%次亜塩素酸ナトリウム漂白液で物の表面を拭うと、芽胞が除去され、患者間の伝播が防がれる[41]。蓋付きのトイレを設置し、水を流す前に蓋を閉じる事も汚染リスクを減少させる[42]。

CDI患者はCDI患者のみを集めた部屋に収容するか、個室に隔離すべきである[39]。

一般的な消毒薬はC. difficile 芽胞には無効であり、寧ろ芽胞形成を促進するが、漂白剤の1⁄10水希釈液は、芽胞を殺す事が出来る[43]。 蒸気化過酸化水素(HPV)でCDI患者退院後の部屋を消毒すると、次の患者のCDI感染リスクを低下させる事が出来る。この操作でCDI発生率は53%[44]又は42%[45]に低下する。紫外線殺菌装置やC. difficile 感染患者退院後専門の病室清掃員を配置すると効果が有る[46]。

治療

C. difficile 無症候性キャリアは多い。症状の無いこれらのキャリアを治療する事の是非は議論が分かれている。一般に、軽症の症状では治療を要しない[4][47]。下痢で脱水状態の患者には経口補水療法をすると良い。

医薬品投与

多くの異なる抗生物質がC. difficile 治療に用いられ、何れもそれなりの効果がある[48]。

- メトロニダゾールは安価であり、軽度から中等度の疾患の選択肢となる[35]。通常は1日3回10日間服用する[49]。

- 経口バンコマイシンは重度の疾患に用いられる[35]。又、メトロニダゾール投与後に下痢が続いている場合にも使用される[49]。メトロニダゾールは先天性障害を引き起こす危険性が有るので、妊婦のC. difficile 感染症については重篤度を問わずバンコマイシンが用いられる[49]。バンコマイシンとメトロニダゾールの有効性は同等であると思われる[47]。通常バンコマイシンは、1日4回10日間投与する[49]。

- フィダキソマイシンは軽度から中等度の疾患に対してバンコマイシンと同等の効果を持つ[50]。バンコマイシンと同程度の忍容性が有り[51]、症状再燃のリスクは少ない[48]。再発性感染症で他の抗生物質が無効な場合に使用すべきである[50]。

ロペラミド等の止瀉薬を用いて下痢を止めようとすると却ってC. difficile 感染症を悪化させるので勧められない[52]。イオン交換樹脂であるコレスチラミンはトキシンA、トキシンBを共に吸着除去するので排便回数を減少させる効果が有り、脱水を予防出来る[53]。コレスチラミンとバンコマイシンの併用が推奨される。免疫抑制状態に有る患者を治療する最後の手段は、免疫グロブリン大量療法(IVIG)である[53]。

共生細菌

治療に於けるプロバイオティクスのエビデンスは不充分であるので[35][54]、標準治療に上乗せして用いたり単独で用いてはならない[55]。

糞便移植

糞便注腸法又は糞便移植法と呼ばれている治療法では、抗生物質が効かなくなった患者の約85%から90%で有効である[56][57]。これは感染症再発の原因である腸内細菌の不均衡を是正する為に健康なドナーから正常な腸内細菌叢を移植する方法である[58]。この方法で抗生物質で破壊された腸内の菌環境が再構築され、C. difficile 増殖が抑制される[59]。副作用は、少なくとも治療後直ぐには殆ど起こらない[57]。

飲み薬の形での腸内細菌移植の試みで効果が上がっている[60]。米国では実施可能な施設はあるが、2015年時点では米国食品医薬品局の認可は得られていない[61]。

手術

重症C. difficile 大腸炎の場合、結腸切除術が予後を改善し得る[62]。どの様な患者の場合に手術で最良の結果が得られるのかを見極める為に、専用の判定基準が定められている[63]。

予後

メトロニダゾール又はバンコマイシンでの最初の治療後、C. difficile 感染症は、約2割の人々で再発する。再発率は、回数を重ねる毎に4割、6割と増加していく[64]。

疫学

C. difficile 下痢症は北米では毎年10万人当り8人の割合で発生していると推計されている[65]。入院患者に限って計算すると、千人当り4〜8人である[65]。2011年には、米国内で50万人が感染し、2万9千人が死亡した[5]。ニューキノロン耐性株が出現した事で、C. difficile 関連死は2000年から2007年での米国での年間死亡数の5倍となった[66]。

歴史

1935年にホール(Hall)とオトゥール(O'Toole)が発見した際には、菌の単離が困難であり、コロニー形成が非常に遅かった事から、Bacillus difficilis と命名された。この名称は1970年に変更された[64][67]。

偽膜性大腸炎は1978年に初めてC. difficile 感染症の合併症として記述され[68]、偽膜性大腸炎患者から毒素が検出されてコッホの原則に合致する処となった。

|publication-date=11 October 2007 |title=Healthcare watchdog finds significant failings in infection control at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust |type=press release |publisher=Healthcare Commission |publication-place=United Kingdom |archivedate=21 December 2007 |url=http://www.healthcarecommission.org.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases.cfm/cit_id/5875/FAArea1/customWidgets.content_view_1/usecache/false |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071221000642/http://www.healthcarecommission.org.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases.cfm?cit_id=5875&FAArea1=customWidgets.content_view_1&usecache=false }}</ref>[69]

- In November 2007, the 027 strain spread into several hospitals in southern Finland, with ten deaths out of 115 infected patients reported on 2007-12-14.[70]

- In November 2009, four deaths at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Ireland have possible links to CDI. A further 12 patients tested positive for infection, and another 20 showed signs of infection.[71]

- From February 2009 to February 2010, 199 patients at Herlev hospital in Denmark were suspected of being infected with the 027 strain. In the first half of 2009, 29 died in hospitals in Copenhagen after they were infected with the bacterium.[72]

- In May 2010, a total of 138 patients at four different hospitals in Denmark were infected with the 027 strain [73] plus there were some isolated occurrences at other hospitals.[74]

- In May 2010, there were 14 fatalities related to the bacterium in the Australian state of Victoria. Two years later, the same strain of the bacterium was detected in New Zealand.[75]

- On 28 May 2011, an outbreak in Ontario had been reported, with 26 fatalities as of 24 July 2011.[76]

- In 2012/2013, a total of 27 people at one hospital in the south of Sweden (Ystad) were infected with 10 deaths. 5 died of the strain 017.[77]-->

治療法の研究開発

- CDA-1及びCDB-1(MDX-066とMDX-1388或いはMBL-CDA1とMBL-CDB1とも言われる)は研究中の1対のモノクローナル抗体であり、C. difficile のトキシンAとトキシンBを其々中和し、CDIを治療する。CDIを既存の抗生物質で治療する場合の補助療法に位置付けられている[78][79][80]。

- ニタゾキサニドは合成ニトロチアゾリルサリチルアミド誘導体であり、抗原虫薬(クリプトスポリジウムとランブル鞭毛虫)として米国で承認されている。CDIへの効果についてバンコマイシンを対照薬として研究が実施されている[81]

- リファキシミン[81]は米国で臨床使用中の半合成リファマイシン系非全身投与抗生物質である。FDAはCDADの治療について承認している。

- 他のCDI治療薬としては、リファラジル[81]、チゲサイクリン[81]、ラモプラニン[81]、リジニラゾール等が開発中である。

- 虫垂がC. difficile にとって重要な意味を持つか否かについて研究されている。虫垂は腸内の善玉菌の住居であると考えられており、2011年の研究では、C. difficile が腸内に侵入した時に、虫垂がそれに対抗する抗体を増加させる作用が有る事が示された。虫垂に有るB細胞は移行して成熟し、抗トキシンA IgA及びIgG抗体を産生し、C. difficile に対抗して善玉菌が生き延びる確率を高めている[82]。

- 毒素を産生しないC. difficile を摂取すると、その後のCDIを予防出来るとの結果が得られている[83]。

関連項目

参考資料

- ^ a b “Clostridium difficile: A Cause of Diarrhea in Children”. JAMA Pediatrics 167 (6): 592. (June 2013). doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2551. PMID 23733223.

- ^ Binion, David G (2010). “Clostridium difficile and IBD”. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Monitor 11 (1): 7–14.

- ^ Curry J (2007年7月20日). “Pseudomembranous Colitis”. WebMD. 2008年11月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 322–4. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9

- ^ a b Lessa, Fernanda C.; Mu, Yi; Bamberg, Wendy M.; Beldavs, Zintars G.; Dumyati, Ghinwa K.; Dunn, John R.; Farley, Monica M.; Holzbauer, Stacy M. et al. (26 February 2015). “Burden of Infection in the United States”. New England Journal of Medicine 372 (9): 825–834. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1408913.

- ^ Liddell-Scott. “κλωστήρ”. Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford){{inconsistent citations}}

- ^ Cawley, Kevin. “Difficilis”. Latin Dictionary and Grammar Aid (University of Notre Dame) 2013年3月16日閲覧。{{inconsistent citations}}

- ^ 國島広之「Clostridium difficile」『臨床検査』第58巻第7号、2008年7月15日、722-3頁、doi:10.11477/mf.1542101657、ISSN 0485-1420、2016年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Inpatient diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infection”. Clinical Medicine 12 (6): 583–588. (2012). doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.12-6-583.

- ^ Bomers, Marije (April 2015). “Rapid, Accurate, and On-Site Detection of C. difficile in Stool Samples”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 110 (4): 588–594. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.90. PMID 25823766.

- ^ “Clinical prediction rules to optimize cytotoxin testing for Clostridium difficile in hospitalized patients with diarrhea”. The American Journal of Medicine 100 (5): 487–95. (May 1996). doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(95)00016-X. PMID 8644759.

- ^ Di Bella, Stefano; Ascenzi, Paolo; Siarakas, Steven; Petrosillo, Nicola; di Masi, Alessandra (2016-01-01). “Clostridium difficile Toxins A and B: Insights into Pathogenic Properties and Extraintestinal Effects”. Toxins 8 (5). doi:10.3390/toxins8050134. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 4885049. PMID 27153087.

- ^ “The low molecular mass GTP-binding protein Rh is affected by toxin a from Clostridium difficile”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 95 (3): 1026–31. (1995). doi:10.1172/JCI117747. PMC 441436. PMID 7883950.

- ^ “Binary Bacterial Toxins: Biochemistry, Biology, and Applications of Common Clostridium and Bacillus Proteins”. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews : MMBR 68 (3): 373–402, table of contents. (2004). doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.3.373-402.2004. PMC 515256. PMID 15353562.

- ^ “A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality”. The New England Journal of Medicine 353 (23): 2442–9. (December 2005). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051639. PMID 16322602.

- ^ McDonald LC (August 2005). “Clostridium difficile: responding to a new threat from an old enemy”. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 26 (8): 672–5. doi:10.1086/502600. PMID 16156321.

- ^ “Clostridium difficile infection: New developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis”. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 7 (7): 526–36. (July 2009). doi:10.1038/nrmicro2164. PMID 19528959.

- ^ Luciano, JA; Zuckerbraun, BS (December 2014). “Clostridium difficile infection: prevention, treatment, and surgical management”. The Surgical clinics of North America 94 (6): 1335–49. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2014.08.006. PMID 25440127.

- ^ “Scientists probe whether C. difficile is linked to eating meat”. CBC News. (2006年10月4日). オリジナルの2006年10月24日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Acquisition of Clostridium difficile by hospitalized patients: evidence for colonized new admissions as a source of infection”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 166 (3): 561–7. (September 1992). doi:10.1093/infdis/166.3.561. PMID 1323621.

- ^ Halsey J (2008). “Current and future treatment modalities for Clostridium difficile-associated disease”. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 65 (8): 705–15. doi:10.2146/ajhp070077. PMID 18387898.

- ^ “Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection”. Archives of Internal Medicine 170 (9): 784–90. (May 2010). doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.89. PMID 20458086.

- ^ “Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy and Clostridium difficile infection in a meta-analysis”. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 10 (3): 225–33. (March 2012). doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.09.030. PMID 22019794.

- ^ Sarah A. Kuehne; Stephen T. Cartman; John T. Heap; Michelle L. Kelly; Alan Cockayne; Nigel P. Minton (2010). “The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection”. Nature 467 (7316): 711–3. doi:10.1038/nature09397. PMID 20844489.

- ^ “Surgical Pathology Criteria: Pseudomembranous Colitis”. Stanford School of Medicine. 2016年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ Manual of Clinical Microbiology (8th ed.). Washington DC: ASM Press. (2003). ISBN 1-55581-255-4[要ページ番号]

- ^ “Repeat Stool Testing to Diagnose Clostridium difficile Infection Using Enzyme Immunoassay Does Not Increase Diagnostic Yield”. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 9 (8): 665–669.e1. (2011). doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.030. PMID 21635969.

- ^ Anna Salleh (2009年3月2日). “Researchers knock down gastro bug myths”. ABC Science Online. 2009年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile”. Nature 458 (7242): 1176–9. (2009). doi:10.1038/nature07822. PMC 2679968. PMID 19252482.

- ^ “Diagnostic accuracy of real-time polymerase chain reaction in detection of Clostridium difficile in the stool samples of patients with suspected Clostridium difficile Infection: a meta-analysis.”. Clinical Infectious Diseases 53 (7): e81–90. (October 2011). doi:10.1093/cid/cir505. PMID 21890762.

- ^ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Origin of Adverse Drug Events in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #158. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. July 2013. [1]

- ^ a b “Fighting fire with fire: is it time to use probiotics to manage pathogenic bacterial diseases?”. Current Gastroenterology Reports 14 (4): 343–8. (August 2012). doi:10.1007/s11894-012-0274-4. PMID 22763792.

- ^ a b “Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”. Annals of Internal Medicine 157 (12): 878–88. (18 December 2012). doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00563. PMID 23362517.

- ^ a b c d e “Probiotics in Clostridium difficile Infection”. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 45 (Suppl): S154–8. (November 2011). doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822ec787. PMID 21992956.

- ^ McFarland LV (April 2006). “Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 101 (4): 812–22. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00465.x. PMID 16635227.

- ^ “Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children.”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5: CD006095. (31 May 2013). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub3. PMID 23728658.

- ^ Mayo Clinic C. diff prevention

- ^ a b “Strategies to Prevent Clostridium difficile Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update.”. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 35 (6): 628–45. (Jun 2014). doi:10.1086/676023. PMID 24799639.

- ^ Roehr B (2007年9月21日). “Alcohol Rub, Antiseptic Wipes Inferior at Removing Clostridium difficile”. Medscape. 2016年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Host S-nitrosylation inhibits clostridial small molecule–activated glucosylating toxins”. Nature Medicine 17 (9): 1136–41. (2011). doi:10.1038/nm.2405. PMC 3277400. PMID 21857653. 非専門家向けの内容要旨 – ScienceDaily (21 August 2011).

- ^ Laidman J (2011年12月29日). “Flush With Germs: Lidless Toilets Spread C. difficile”. Medscape. 2016年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Cleaning agents 'make bug strong'”. BBC News Online. (2006年4月3日) 2008年11月17日閲覧。

- ^ Boyce et al. 2008

- ^ Manian et al. 2010

- ^ “Performance Feedback, Ultraviolet Cleaning Device, and Dedicated Housekeeping Team Significantly Improve Room Cleaning, Reduce Potential for Spread of Common, Dangerous Infection”. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014年1月15日). 2014年1月20日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Antibiotic treatment for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults.”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD004610. (7 September 2011). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004610.pub4. PMID 21901692.

- ^ a b “Comparative effectiveness of Clostridium difficile treatments: a systematic review”. Annals of Internal Medicine 155 (12): 839–47. (20 December 2011). doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00007. PMID 22184691.

- ^ a b c d Surawicz, Christina M; Brandt, Lawrence J; Binion, David G; Ananthakrishnan, Ashwin N; Curry, Scott R; Gilligan, Peter H; McFarland, Lynne V; Mellow, Mark et al. (26 February 2013). “Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Clostridium difficile Infections”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 108 (4): 478–498. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.4. PMID 23439232.

- ^ a b “Fidaxomicin: a novel macrocyclic antibiotic for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection.”. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 69 (11): 933–43. (1 June 2012). doi:10.2146/ajhp110371. PMID 22610025.

- ^ Cornely OA (December 2012). “Current and emerging management options for Clostridium difficile infection: what is the role of fidaxomicin?”. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 18 Suppl 6: 28–35. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12012. PMID 23121552.

- ^ Cunha, Burke A. (2013). Antibiotic Essentials 2013 (12 ed.). p. 133. ISBN 978-1-284-03678-7

- ^ a b Stroehlein JR (2004). “Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection”. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 7 (3): 235–9. doi:10.1007/s11938-004-0044-y. PMID 15149585.

- ^ “Clostridium difficile: controversies and approaches to management”. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 22 (6): 517–24. (December 2009). doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833229ce. PMID 19738464.

- ^ Pillai A, Nelson R (23 January 2008). Pillai, Anjana. ed. “Probiotics for treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated colitis in adults”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004611. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004611.pub2. PMID 18254055.

- ^ “Fecal Transplantation for Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection in Older Adults: A Review.”. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 61 (8): 1394–8. (August 2013). doi:10.1111/jgs.12378. PMID 23869970.

- ^ a b Drekonja, D; Reich, J; Gezahegn, S; Greer, N; Shaukat, A; MacDonald, R; Rutks, I; Wilt, TJ (5 May 2015). “Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review”. Annals of Internal Medicine 162 (9): 630–8. doi:10.7326/m14-2693. PMID 25938992.

- ^ “Duodenal Infusion of Donor Feces for Recurrent Clostridium difficile”. The New England Journal of Medicine 368 (5): 407–15. (January 2013). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. PMID 23323867.

- ^ Jop De Vrieze (30 August 2011). “The Promise of Poop”. Science 341: 954–957. doi:10.1126/science.341.6149.954.

- ^ Keller, JJ; Kuijper, EJ (2015). “Treatment of recurrent and severe Clostridium difficile infection”. Annual Review of Medicine 66: 373–86. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-070813-114317. PMID 25587656.

- ^ Smith, Peter Andrey (2015年11月10日). “Fecal Transplants Made (Somewhat) More Palatable”. The New York Times: p. D5 2015年11月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following emergency surgery for Clostridium difficile colitis”. The British Journal of Surgery 99 (11): 1501–13. (November 2012). doi:10.1002/bjs.8868. PMID 22972525.

- ^ “Emergency colectomy for fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis: Striking the right balance”. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 46 (10): 1222–7. (October 2011). doi:10.3109/00365521.2011.605469. PMID 21843039.

- ^ a b “Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever”. The New England Journal of Medicine 359 (18): 1932–40. (October 2008). doi:10.1056/NEJMra0707500. PMID 18971494.

- ^ a b others], editor-in-chief, Frank J. Domino ; associate editors, Robert A. Baldor (2014). The 5-minute clinical consult 2014 (22nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-4511-8850-9

- ^ “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013”. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013年). 2014年11月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Intestinal flora in newborn infants with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficilis”. American Journal of Diseases of Children 49 (2): 390–402. (1935). doi:10.1001/archpedi.1935.01970020105010.

- ^ “Clostridium difficile and the aetiology of pseudomembranous colitis”. Lancet 311 (8073): 1063–6. (May 1978). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90912-1. PMID 77366.

- ^ Smith, Rebecca; Rayner, Gordon; Adams, Stephen (2007年10月11日). “Health Secretary intervenes in superbug row”. Daily Telegraph (London)

- ^ Ärhäkkä suolistobakteeri on tappanut jo kymmenen potilasta – HS.fi – Kotimaa

- ^ “Possible C Diff link to Drogheda deaths”. RTÉ News. (2009年11月10日)

- ^ 199 hit by the killer diarrhea at Herlev Hospital, BT 3 March 2010

- ^ (Herlev, Amager, Gentofte and Hvidovre)

- ^ Four hospitals affected by the dangerous bacterium, TV2 News 7 May 2010

- ^ “Deadly superbug reaches NZ”. 3 News NZ. (2012年10月30日)

- ^ “C. difficile linked to 26th death in Ontario”. CBC News. (2011年7月25日) 2011年7月24日閲覧。

- ^ “10 punkter för att förhindra smittspridning i Region Skåne” [10 points to prevent the spread of infection in Region Skåne] (スウェーデン語). 2015年3月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ Campus, University of Massachusetts Worcester. “op-line data from randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled Phase 2 clinical trial indicate statistically significant reduction in recurrences of CDAD”. 2010年12月27日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年8月16日閲覧。

- ^ CenterWatch. “Clostridium Difficile-Associated Diarrhea”. 2011年8月16日閲覧。

- ^ Business, Highbeam. “MDX 066, MDX 1388 Medarex, University of Massachusetts Medical School clinical data (phase II)(diarrhea)”. 2011年8月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Shah D, Dang MD, Hasbun R, Koo HL, Jiang ZD, DuPont HL, Garey KW; Dang; Hasbun; Koo; Jiang; Dupont; Garey (May 2010). “Clostridium difficile infection: update on emerging antibiotic treatment options and antibiotic resistance”. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy 8 (5): 555–64. doi:10.1586/eri.10.28. PMC 3138198. PMID 20455684.

- ^ Barlow, Andrew; Muhleman, Mitchel; Gielecki, Jerzy; Matusz, Petru; Tubbs, R. Shane; Loukas, Marios (2013). “The Vermiform Appendix: A Review”. Clinical Anatomy 26 (7): 833–842. doi:10.1002/ca.22269. PMID 23716128.

- ^ Gerding, Dale N.; Meyer, Thomas; Lee, Christine; Cohen, Stuart H.; Murthy, Uma K.; Poirier, Andre; Van Schooneveld, Trevor C.; Pardi, Darrell S. et al. (5 May 2015). “Administration of Spores of Nontoxigenic Strain M3 for Prevention of Recurrent Infection”. JAMA 313 (17): 1719. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3725.