「核膜」の版間の差分

Smilesworth (会話 | 投稿記録) リンクの追加など |

Smilesworth (会話 | 投稿記録) en:Nuclear envelope (20:57, 10 February 2019 UTC) を翻訳して加筆・一部再構成 タグ: サイズの大幅な増減 ビジュアルエディター: 中途切替 |

||

| 3行目: | 3行目: | ||

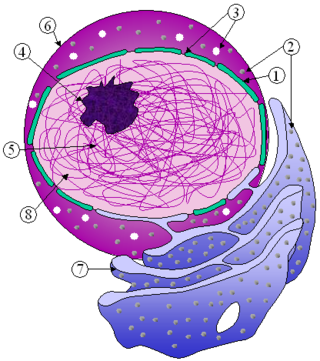

[[Image:nucleus_ER.png|thumb|right|320px|'''細胞核の概要'''(1) '''核膜''' (2) [[リボソーム]] (3) [[核膜孔]] (4) [[核小体]] |

[[Image:nucleus_ER.png|thumb|right|320px|'''細胞核の概要'''(1) '''核膜''' (2) [[リボソーム]] (3) [[核膜孔]] (4) [[核小体]] |

||

(5) [[クロマチン]] (6) [[細胞核]] (7) [[小胞体]] (8) [[核質]]]] |

(5) [[クロマチン]] (6) [[細胞核]] (7) [[小胞体]] (8) [[核質]]]] |

||

'''核膜'''(かくまく、{{lang-en-short|nuclear membrane, nuclear envelope}})は、[[真核生物]]の[[細胞核|核]]を[[細胞質]]から隔てている[[生体膜]]を |

'''核膜'''(かくまく、{{lang-en-short|nuclear membrane, nuclear envelope}})は、[[真核生物]]の[[細胞核|核]]を[[細胞質]]から隔てている[[生体膜]]であり、[[ゲノム|遺伝物質]]を内包している。内膜と外膜からなる二重の[[脂質二重層]]構造をとり、外膜は[[小胞体]]とつながっている<ref name="Alberts2">{{cite book|last1=Alberts|first1=Bruce|title=Molecular biology of the cell|date=2002|publisher=Garland|location=New York [u.a.]|isbn=0815340729|page=197|edition=4th}}</ref>。内膜と外膜の空間は核膜槽 (perinuclear space)と呼ばれ、その幅は約 20–40 nmである<ref name=":0">{{cite web|title=Perinuclear space|url=http://www.biology-online.org/dictionary/Perinuclear_space|work=Dictionary|publisher=Biology Online|accessdate=7 December 2012}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{cite book|last1=Berrios|first1=Miguel, ed.|title=Nuclear structure and function.|date=1998|publisher=Academic Press|location=San Diego|isbn=9780125641555|page=4}}</ref>。核膜に存在する[[核膜孔]]は多数の[[タンパク質]]からなる核膜孔複合体で構成され、核の内外を移動する物質の通り道となっている<ref name="Alberts2" />。内膜の内側 ([[核質]]側) には[[ラミン]]からなる[[中間径フィラメント]]が格子状に裏打ち構造 ({{仮リンク|核ラミナ|en|Nuclear lamina}}) を形成し、核の形態を保っている。中間径フィラメントは外膜の外側にもより緩やかな構造を形成し、核膜の構造的支持を行っている<ref name="Alberts2" />。 |

||

核膜は[[細胞分裂]]の際に一時消失することがあるが終期には再形成される。 |

核膜は[[細胞分裂]]の際に一時消失することがあるが[[終期 (細胞分裂)|終期]]には再形成される。 |

||

==構造== |

|||

核膜は、内膜と外膜からなる二重の[[脂質二重層]]構造である。内膜と外膜は、[[核膜孔]]によって互いに連結されている。2種類の[[中間径フィラメント]]のネットワークが核膜の支持を行っている。内側のネットワークは内膜の内側に形成される{{仮リンク|核ラミナ|en|Nuclear lamina}}である<ref name="Coutinho">{{cite web|last1=Coutinho|first1=Henrique Douglas M|last2=Falcão-Silva|first2=Vivyanne S|last3=Gonçalves|first3=Gregório Fernandes|last4=da Nóbrega|first4=Raphael Batista|title=Molecular ageing in progeroid syndromes: Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome as a model|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2674425/figure/F1/|website=Immunity & Ageing : I & A|accessdate=11 March 2018|pages=4|doi=10.1186/1742-4933-6-4|date=20 April 2009}}</ref>。外膜の外側でもより緩やかなネットワークが形成され、外側からの支持を行っている<ref name="Alberts2" />。 |

|||

===外膜=== |

|||

外膜は[[小胞体]]の膜と連続している<ref name=":2">{{cite web|title=Chloride channels in the Nuclear membrane|url=http://clapham.tch.harvard.edu/publications/pdf/Tabares_JMB_91.pdf|publisher=Harvard.edu|accessdate=7 December 2012}}</ref>。外膜は小胞体の膜は物理的に連結されている一方で、小胞体の膜よりもはるかに高濃度の[[タンパク質]]を含んでいる<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI">{{cite journal|last=Hetzer|first=Mertin|date=February 3, 2010|title=The Nuclear Envelope|journal=Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology|volume=2|issue=3|pages=a000539|doi=10.1101/cshperspect.a000539|pmid=20300205|pmc=2829960}}</ref>。[[哺乳類]]に存在する4つの{{仮リンク|ネスプリン|en|Nesprin}} (nuclear envelope spectrin repeat, nesprin) タンパク質は、すべて外膜に発現している<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=Wilson|first=Katherine L.|last2=Berk|first2=Jason M.|date=2010-06-15|title=The nuclear envelope at a glance|url=http://jcs.biologists.org/content/123/12/1973|journal=J Cell Sci|volume=123|issue=12|pages=1973–1978|language=en|doi=10.1242/jcs.019042|issn=0021-9533|pmid=20519579|pmc=2880010}}</ref>。ネスプリンタンパク質は{{仮リンク|KASHドメイン|en|KASH domains}}を持っており、{{仮リンク|LINC複合体|en|LINC complex}} (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex) の一部として、[[細胞骨格]]繊維と核の骨格を連結している<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Burke|first=Brian|last2=Roux|first2=Kyle J.|date=2009-11-01|title=Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location|journal=Developmental Cell|volume=17|issue=5|pages=587–597|doi=10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018|issn=1878-1551|pmid=19922864}}</ref><ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last=Crisp|first=Melissa|last2=Liu|first2=Qian|last3=Roux|first3=Kyle|last4=Rattner|first4=J. B.|last5=Shanahan|first5=Catherine|last6=Burke|first6=Brian|last7=Stahl|first7=Phillip D.|last8=Hodzic|first8=Didier|date=2006-01-02|title=Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex|journal=The Journal of Cell Biology|volume=172|issue=1|pages=41–53|doi=10.1083/jcb.200509124|issn=0021-9525|pmid=16380439|pmc=2063530}}</ref><ref name="Zeng">{{cite journal|last1=Zeng et. al|first1=X|date=2017|title=Nuclear Envelope-Associated Chromosome Dynamics during Meiotic Prophase I.|journal=Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology|volume=5|pages=121|doi=10.3389/fcell.2017.00121|pmid=29376050}}</ref>。ネスプリンを介した細胞骨格への連結は、核の配置と細胞の[[機械受容器|機械受容]]機能に寄与している<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal|last=Uzer|first=Gunes|last2=Thompson|first2=William R.|last3=Sen|first3=Buer|last4=Xie|first4=Zhihui|last5=Yen|first5=Sherwin S.|last6=Miller|first6=Sean|last7=Bas|first7=Guniz|last8=Styner|first8=Maya|last9=Rubin|first9=Clinton T.|date=2015-06-01|title=Cell Mechanosensitivity to Extremely Low-Magnitude Signals Is Enabled by a LINCed Nucleus|url=http://europepmc.org/articles/pmc4458857|journal=Stem Cells|volume=33|issue=6|pages=2063–2076|language=en|doi=10.1002/stem.2004|issn=1066-5099|pmid=25787126|pmc=4458857}}</ref>。ネスプリン-1とネスプリン-2は[[アクチン]]繊維のような細胞骨格の構成要素と直接結合したり、核膜槽のタンパク質と結合したりする<ref name=":5" /><ref name="Zeng" />。ネスプリン-3とネスプリン-4は、核輸送の「積み荷」を降ろす過程に寄与している可能性がある。ネスプリン-3は{{仮リンク|プレクチン|en|Plectin}} (plectin) に結合し、核膜と細胞質の中間径フィラメントを連結している<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal|last=Wilhelmsen|first=Kevin|last2=Litjens|first2=Sandy H. M.|last3=Kuikman|first3=Ingrid|last4=Tshimbalanga|first4=Ntambua|last5=Janssen|first5=Hans|last6=van den Bout|first6=Iman|last7=Raymond|first7=Karine|last8=Sonnenberg|first8=Arnoud|date=2005-12-05|title=Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin|journal=The Journal of Cell Biology|volume=171|issue=5|pages=799–810|doi=10.1083/jcb.200506083|issn=0021-9525|pmid=16330710|pmc=2171291}}</ref>。ネスプリン-4は、[[微小管]]の+端方向へ移動する[[モータータンパク質]]の[[キネシン|キネシン-1]]と結合する<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal|last=Roux|first=Kyle J.|last2=Crisp|first2=Melissa L.|last3=Liu|first3=Qian|last4=Kim|first4=Daein|last5=Kozlov|first5=Serguei|last6=Stewart|first6=Colin L.|last7=Burke|first7=Brian|date=2009-02-17|title=Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|volume=106|issue=7|pages=2194–2199|doi=10.1073/pnas.0808602106|issn=1091-6490|pmid=19164528|pmc=2650131}}</ref>。また、外膜は内膜と融合して核膜孔を形成し、この過程は細胞の成長に寄与している<ref name=":9">{{Cite journal|last=Fichtman|first=Boris|last2=Ramos|first2=Corinne|last3=Rasala|first3=Beth|last4=Harel|first4=Amnon|last5=Forbes|first5=Douglass J.|date=2010-12-01|title=Inner/Outer Nuclear Membrane Fusion in Nuclear Pore Assembly|journal=Molecular Biology of the Cell|volume=21|issue=23|pages=4197–4211|doi=10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0309|issn=1059-1524|pmid=20926687|pmc=2993748}}</ref>。 |

|||

===内膜=== |

|||

{{Further |{{仮リンク|核の内膜のタンパク質|en|Inner nuclear membrane proteins}}}} |

|||

内膜は[[核質]]を包んでおり、内膜の内側は核ラミナと呼ばれるメッシュ状の中間径フィラメントで覆われている。核ラミナの厚さは約 10–40 nmで、核膜を安定化するとともに、[[クロマチン]]の機能や[[遺伝子発現]]にも関与している<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" />。内膜は、核膜を貫く核膜孔によって外膜と連結されている。内膜と外膜は小胞体の膜と連結しているものの、膜に埋め込まれているタンパク質は連続体中へ拡散するよりも、むしろその場に留まる傾向にある<ref name="Inner membrane—EMBO">{{cite journal|date=April 19, 2001|title=The inner nuclear membrane: simple, or very complex?|url=http://www.nature.com/emboj/journal/v20/n12/full/7593796a.html|journal=The EMBO Journal|volume=20|issue=12|pages=2989–2994|accessdate=7 December 2012|doi=10.1093/emboj/20.12.2989|pmid=11406575|pmc=150211}}</ref>。 |

|||

内膜のタンパク質の[[変異]]は、いくつかの{{仮リンク|ラミノパシー|en|Laminopathy}}と呼ばれる疾患を引き起こす。 |

|||

===核膜孔=== |

|||

{{main|核膜孔}} |

|||

核膜には、核膜孔による穴が数千個程度存在する。核膜孔は直径約 100 nmのタンパク質複合体で、内側のチャネルの直径は約 40 nmである<ref name=TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI />。核膜孔は内膜と外膜を連結している。 |

|||

==細胞分裂== |

|||

[[細胞周期]]{{仮リンク|間期|en|Interphase}}の[[G2期]]の間、核膜は表面積を増し、核膜孔の数は倍増する<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" />。[[酵母]]のような[[真核生物]]ではclosed mitosisという形式の[[有糸分裂]]が行われ、核膜は[[細胞分裂]]中も形成されたままである。[[紡錘糸]]は核膜の内部で形成されるか、核膜をばらばらにすることなく貫通する<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" />。他の真核生物 (動物や植物など) ではopen mitosisという形式の[[有糸分裂]]が行われ、紡錘糸が内部の[[染色体]]にアクセスできるよう、核膜は{{仮リンク|前中期|en|Prometaphase}}の間に解体されなければならない。核膜の解体と再形成の過程はあまり解明されていない。 |

|||

===解体=== |

|||

哺乳類では、有糸分裂初期の一連の段階の後、核膜は数分以内に解体される。まず、{{仮リンク|サイクリン依存性キナーゼ|en|Cyclin-dependent kinase|label=M-Cdk}}が{{仮リンク|ヌクレオポリン|en|Nucleoporin}}のポリペプチドを[[リン酸化]]し、それらは核膜孔複合体から選択的に除去される。その後、核膜孔複合体の残りの部分が同時に解体される。核膜孔複合体は小さなポリペプチドの断片へ分解されるのではなく、いくつかの安定なパーツへ解体されることが、[[生化学]]的な証拠からは示唆される<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" />。また、M-Cdkは核ラミナの要素をリン酸化して解体し、核膜は小さな[[小胞]]へと解体される<ref name=":10">{{cite book|last=Alberts (et al)|title=Molecular Biology of The Cell|year=2008|publisher=Garland Science|location=New York|isbn=978-0-8153-4106-2|pages=1079–1080|edition=5th|chapter=Chapter 17: The Cell Cycle}}</ref>。核膜が小胞体へ吸収されるという強力な証拠が[[電子顕微鏡]]と[[蛍光顕微鏡]]から得られており、通常小胞体では見られない核内タンパク質が有糸分裂中には出現する<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" />。 |

|||

哺乳類細胞では、有糸分裂前中期の核膜の解体以外にも、細胞の移動によって核膜が破れることがある<ref name="pmid27013426">{{cite journal|year=2016|title=ESCRT III repairs nuclear envelope ruptures during cell migration to limit DNA damage and cell death|url=|journal=Science|volume=352|issue=6283|pages=359–62|doi=10.1126/science.aad7611|pmid=27013426|vauthors=Raab M, Gentili M, de Belly H, Thiam HR, Vargas P, Jimenez AJ, Lautenschlaeger F, Voituriez R, Lennon-Duménil AM, Manel N, Piel M}}</ref>。この一時的な破壊は、細胞質のタンパク質複合体{{仮リンク|ESCRT|en|ESCRT}} (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) によって迅速に修復される<ref name="pmid27013426" />。核膜が破れている間は、DNAの2本鎖切断も引き起こされる。限られた環境を通って移動する細胞の生存は、効率的な核膜とDNAの修復装置に依存していると考えられる。 |

|||

核膜の解体の異常はラミノパシーやがん細胞でも観察され、細胞のタンパク質の誤った局在、小核の形成やゲノムの不安定性をもたらす<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Vargas|first=Jesse D.|last2=Hatch|first2=Emily M.|last3=Anderson|first3=Daniel J.|last4=Hetzer|first4=Martin W.|date=2012-1|title=Transient nuclear envelope rupturing during interphase in human cancer cells|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22567193|journal=Nucleus (Austin, Tex.)|volume=3|issue=1|pages=88–100|doi=10.4161/nucl.18954|issn=1949-1042|pmid=22567193|pmc=PMC3342953}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lim|first=Sanghee|last2=Quinton|first2=Ryan J.|last3=Ganem|first3=Neil J.|date=11 01, 2016|title=Nuclear envelope rupture drives genome instability in cancer|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27799497|journal=Molecular Biology of the Cell|volume=27|issue=21|pages=3210–3213|doi=10.1091/mbc.E16-02-0098|issn=1939-4586|pmid=27799497|pmc=PMC5170854}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hatch|first=Emily M.|last2=Hetzer|first2=Martin W.|date=2016-10-10|title=Nuclear envelope rupture is induced by actin-based nucleus confinement|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27697922|journal=The Journal of Cell Biology|volume=215|issue=1|pages=27–36|doi=10.1083/jcb.201603053|issn=1540-8140|pmid=27697922|pmc=PMC5057282}}</ref>。 |

|||

===再形成=== |

|||

[[終期 (細胞分裂)|終期]]において核膜が再形成される正確な機構については議論があり、2つの理論が存在する<ref name="TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" />。 |

|||

*{{仮リンク|小胞の融合|en|Vesicle fusion}}: 核膜の小胞が互いに融合し、核膜が再構築される。 |

|||

*小胞体の整形: 小胞体の吸収された核膜を含む部分が核の空間を包み、閉じた膜が再形成される。 |

|||

==起源== |

|||

[[比較ゲノミクス]]や[[進化]]、核膜の起源についての研究からは、核は原始的な真核生物の祖先に出現し、[[古細菌]]と[[細菌]]の[[共生]]によって引き起こされたことが提唱されている<ref name="pmid15611647">{{cite journal|year=2004|title=Comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex|url=|journal=Cell Cycle|volume=3|issue=12|pages=1612–37|doi=10.4161/cc.3.12.1316|pmid=15611647|vauthors=Mans BJ, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Koonin EV}}</ref>。核膜の進化的起源についてはいくつかの考えが提唱されており、[[原核生物]]の祖先の細胞膜の陥入、古細菌宿主中に始原的[[ミトコンドリア]]の存在が確立されたことに伴う新規の膜系の形成、などが唱えられている<ref name="pmid16242992">{{cite journal|year=2005|title=Archaebacteria (Archaea) and the origin of the eukaryotic nucleus|url=|journal=Curr. Opin. Microbiol.|volume=8|issue=6|pages=630–7|doi=10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.004|pmid=16242992|vauthors=Martin W}}</ref>。核膜の適応的機能としては、ミトコンドリアの祖先によって細胞中で産生される[[活性酸素種]]から[[ゲノム]]を保護する障壁となっていた可能性がある<ref name="pmid26577075">{{cite journal|year=2015|title=Birth of the eukaryotes by a set of reactive innovations: New insights force us to relinquish gradual models|url=|journal=BioEssays|volume=37|issue=12|pages=1268–76|doi=10.1002/bies.201500107|pmid=26577075|vauthors=Speijer D}}</ref><ref name=":11">Bernstein H, Bernstein C. Sexual communication in archaea, the precursor to meiosis. pp. 103-117 in Biocommunication of Archaea (Guenther Witzany, ed.) 2017. Springer International Publishing {{ISBN|978-3-319-65535-2}} DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-65536-9</ref>。 |

|||

==出典== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==外部リンク== |

|||

{{Commons category|Nuclear membranes}} |

{{Commons category|Nuclear membranes}} |

||

* {{BUHistology|20102loa}} |

|||

* [http://sspatel.googlepages.com/nuclearporecomplex Animations of nuclear pores and transport through the nuclear envelope] |

|||

* [http://sspatel.googlepages.com/nuclearporecomplex2 Illustrations of nuclear pores and transport through the nuclear membrane] |

|||

* {{MeshName|Nuclear+membrane}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:かくまく}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:かくまく}} |

||

[[Category:細胞解剖学]] |

[[Category:細胞解剖学]] |

||

2019年2月24日 (日) 07:41時点における版

表面に核膜が示されている

核膜(かくまく、英: nuclear membrane, nuclear envelope)は、真核生物の核を細胞質から隔てている生体膜であり、遺伝物質を内包している。内膜と外膜からなる二重の脂質二重層構造をとり、外膜は小胞体とつながっている[1]。内膜と外膜の空間は核膜槽 (perinuclear space)と呼ばれ、その幅は約 20–40 nmである[2][3]。核膜に存在する核膜孔は多数のタンパク質からなる核膜孔複合体で構成され、核の内外を移動する物質の通り道となっている[1]。内膜の内側 (核質側) にはラミンからなる中間径フィラメントが格子状に裏打ち構造 (核ラミナ) を形成し、核の形態を保っている。中間径フィラメントは外膜の外側にもより緩やかな構造を形成し、核膜の構造的支持を行っている[1]。

核膜は細胞分裂の際に一時消失することがあるが終期には再形成される。

構造

核膜は、内膜と外膜からなる二重の脂質二重層構造である。内膜と外膜は、核膜孔によって互いに連結されている。2種類の中間径フィラメントのネットワークが核膜の支持を行っている。内側のネットワークは内膜の内側に形成される核ラミナである[4]。外膜の外側でもより緩やかなネットワークが形成され、外側からの支持を行っている[1]。

外膜

外膜は小胞体の膜と連続している[5]。外膜は小胞体の膜は物理的に連結されている一方で、小胞体の膜よりもはるかに高濃度のタンパク質を含んでいる[6]。哺乳類に存在する4つのネスプリン (nuclear envelope spectrin repeat, nesprin) タンパク質は、すべて外膜に発現している[7]。ネスプリンタンパク質はKASHドメインを持っており、LINC複合体 (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex) の一部として、細胞骨格繊維と核の骨格を連結している[8][9][10]。ネスプリンを介した細胞骨格への連結は、核の配置と細胞の機械受容機能に寄与している[11]。ネスプリン-1とネスプリン-2はアクチン繊維のような細胞骨格の構成要素と直接結合したり、核膜槽のタンパク質と結合したりする[9][10]。ネスプリン-3とネスプリン-4は、核輸送の「積み荷」を降ろす過程に寄与している可能性がある。ネスプリン-3はプレクチン (plectin) に結合し、核膜と細胞質の中間径フィラメントを連結している[12]。ネスプリン-4は、微小管の+端方向へ移動するモータータンパク質のキネシン-1と結合する[13]。また、外膜は内膜と融合して核膜孔を形成し、この過程は細胞の成長に寄与している[14]。

内膜

内膜は核質を包んでおり、内膜の内側は核ラミナと呼ばれるメッシュ状の中間径フィラメントで覆われている。核ラミナの厚さは約 10–40 nmで、核膜を安定化するとともに、クロマチンの機能や遺伝子発現にも関与している[6]。内膜は、核膜を貫く核膜孔によって外膜と連結されている。内膜と外膜は小胞体の膜と連結しているものの、膜に埋め込まれているタンパク質は連続体中へ拡散するよりも、むしろその場に留まる傾向にある[15]。

内膜のタンパク質の変異は、いくつかのラミノパシーと呼ばれる疾患を引き起こす。

核膜孔

核膜には、核膜孔による穴が数千個程度存在する。核膜孔は直径約 100 nmのタンパク質複合体で、内側のチャネルの直径は約 40 nmである[6]。核膜孔は内膜と外膜を連結している。

細胞分裂

細胞周期間期のG2期の間、核膜は表面積を増し、核膜孔の数は倍増する[6]。酵母のような真核生物ではclosed mitosisという形式の有糸分裂が行われ、核膜は細胞分裂中も形成されたままである。紡錘糸は核膜の内部で形成されるか、核膜をばらばらにすることなく貫通する[6]。他の真核生物 (動物や植物など) ではopen mitosisという形式の有糸分裂が行われ、紡錘糸が内部の染色体にアクセスできるよう、核膜は前中期の間に解体されなければならない。核膜の解体と再形成の過程はあまり解明されていない。

解体

哺乳類では、有糸分裂初期の一連の段階の後、核膜は数分以内に解体される。まず、M-Cdkがヌクレオポリンのポリペプチドをリン酸化し、それらは核膜孔複合体から選択的に除去される。その後、核膜孔複合体の残りの部分が同時に解体される。核膜孔複合体は小さなポリペプチドの断片へ分解されるのではなく、いくつかの安定なパーツへ解体されることが、生化学的な証拠からは示唆される[6]。また、M-Cdkは核ラミナの要素をリン酸化して解体し、核膜は小さな小胞へと解体される[16]。核膜が小胞体へ吸収されるという強力な証拠が電子顕微鏡と蛍光顕微鏡から得られており、通常小胞体では見られない核内タンパク質が有糸分裂中には出現する[6]。

哺乳類細胞では、有糸分裂前中期の核膜の解体以外にも、細胞の移動によって核膜が破れることがある[17]。この一時的な破壊は、細胞質のタンパク質複合体ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) によって迅速に修復される[17]。核膜が破れている間は、DNAの2本鎖切断も引き起こされる。限られた環境を通って移動する細胞の生存は、効率的な核膜とDNAの修復装置に依存していると考えられる。

核膜の解体の異常はラミノパシーやがん細胞でも観察され、細胞のタンパク質の誤った局在、小核の形成やゲノムの不安定性をもたらす[18][19][20]。

再形成

終期において核膜が再形成される正確な機構については議論があり、2つの理論が存在する[6]。

- 小胞の融合: 核膜の小胞が互いに融合し、核膜が再構築される。

- 小胞体の整形: 小胞体の吸収された核膜を含む部分が核の空間を包み、閉じた膜が再形成される。

起源

比較ゲノミクスや進化、核膜の起源についての研究からは、核は原始的な真核生物の祖先に出現し、古細菌と細菌の共生によって引き起こされたことが提唱されている[21]。核膜の進化的起源についてはいくつかの考えが提唱されており、原核生物の祖先の細胞膜の陥入、古細菌宿主中に始原的ミトコンドリアの存在が確立されたことに伴う新規の膜系の形成、などが唱えられている[22]。核膜の適応的機能としては、ミトコンドリアの祖先によって細胞中で産生される活性酸素種からゲノムを保護する障壁となっていた可能性がある[23][24]。

出典

- ^ a b c d Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York [u.a.]: Garland. p. 197. ISBN 0815340729

- ^ “Perinuclear space”. Dictionary. Biology Online. 2012年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ Berrios, Miguel, ed. (1998). Nuclear structure and function.. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780125641555

- ^ “Molecular ageing in progeroid syndromes: Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome as a model”. Immunity & Ageing : I & A. pp. 4 (2009年4月20日). doi:10.1186/1742-4933-6-4. 2018年3月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Chloride channels in the Nuclear membrane”. Harvard.edu. 2012年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hetzer, Mertin (February 3, 2010). “The Nuclear Envelope”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2 (3): a000539. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMC 2829960. PMID 20300205.

- ^ Wilson, Katherine L.; Berk, Jason M. (2010-06-15). “The nuclear envelope at a glance” (英語). J Cell Sci 123 (12): 1973–1978. doi:10.1242/jcs.019042. ISSN 0021-9533. PMC 2880010. PMID 20519579.

- ^ Burke, Brian; Roux, Kyle J. (2009-11-01). “Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location”. Developmental Cell 17 (5): 587–597. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018. ISSN 1878-1551. PMID 19922864.

- ^ a b Crisp, Melissa; Liu, Qian; Roux, Kyle; Rattner, J. B.; Shanahan, Catherine; Burke, Brian; Stahl, Phillip D.; Hodzic, Didier (2006-01-02). “Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex”. The Journal of Cell Biology 172 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1083/jcb.200509124. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2063530. PMID 16380439.

- ^ a b Zeng et. al, X (2017). “Nuclear Envelope-Associated Chromosome Dynamics during Meiotic Prophase I.”. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 5: 121. doi:10.3389/fcell.2017.00121. PMID 29376050.

- ^ Uzer, Gunes; Thompson, William R.; Sen, Buer; Xie, Zhihui; Yen, Sherwin S.; Miller, Sean; Bas, Guniz; Styner, Maya et al. (2015-06-01). “Cell Mechanosensitivity to Extremely Low-Magnitude Signals Is Enabled by a LINCed Nucleus” (英語). Stem Cells 33 (6): 2063–2076. doi:10.1002/stem.2004. ISSN 1066-5099. PMC 4458857. PMID 25787126.

- ^ Wilhelmsen, Kevin; Litjens, Sandy H. M.; Kuikman, Ingrid; Tshimbalanga, Ntambua; Janssen, Hans; van den Bout, Iman; Raymond, Karine; Sonnenberg, Arnoud (2005-12-05). “Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin”. The Journal of Cell Biology 171 (5): 799–810. doi:10.1083/jcb.200506083. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2171291. PMID 16330710.

- ^ Roux, Kyle J.; Crisp, Melissa L.; Liu, Qian; Kim, Daein; Kozlov, Serguei; Stewart, Colin L.; Burke, Brian (2009-02-17). “Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (7): 2194–2199. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808602106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2650131. PMID 19164528.

- ^ Fichtman, Boris; Ramos, Corinne; Rasala, Beth; Harel, Amnon; Forbes, Douglass J. (2010-12-01). “Inner/Outer Nuclear Membrane Fusion in Nuclear Pore Assembly”. Molecular Biology of the Cell 21 (23): 4197–4211. doi:10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0309. ISSN 1059-1524. PMC 2993748. PMID 20926687.

- ^ “The inner nuclear membrane: simple, or very complex?”. The EMBO Journal 20 (12): 2989–2994. (April 19, 2001). doi:10.1093/emboj/20.12.2989. PMC 150211. PMID 11406575 2012年12月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Alberts (et al) (2008). “Chapter 17: The Cell Cycle”. Molecular Biology of The Cell (5th ed.). New York: Garland Science. pp. 1079–1080. ISBN 978-0-8153-4106-2

- ^ a b “ESCRT III repairs nuclear envelope ruptures during cell migration to limit DNA damage and cell death”. Science 352 (6283): 359–62. (2016). doi:10.1126/science.aad7611. PMID 27013426.

- ^ Vargas, Jesse D.; Hatch, Emily M.; Anderson, Daniel J.; Hetzer, Martin W. (2012-1). “Transient nuclear envelope rupturing during interphase in human cancer cells”. Nucleus (Austin, Tex.) 3 (1): 88–100. doi:10.4161/nucl.18954. ISSN 1949-1042. PMC PMC3342953. PMID 22567193.

- ^ Lim, Sanghee; Quinton, Ryan J.; Ganem, Neil J. (11 01, 2016). “Nuclear envelope rupture drives genome instability in cancer”. Molecular Biology of the Cell 27 (21): 3210–3213. doi:10.1091/mbc.E16-02-0098. ISSN 1939-4586. PMC PMC5170854. PMID 27799497.

- ^ Hatch, Emily M.; Hetzer, Martin W. (2016-10-10). “Nuclear envelope rupture is induced by actin-based nucleus confinement”. The Journal of Cell Biology 215 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1083/jcb.201603053. ISSN 1540-8140. PMC PMC5057282. PMID 27697922.

- ^ “Comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex”. Cell Cycle 3 (12): 1612–37. (2004). doi:10.4161/cc.3.12.1316. PMID 15611647.

- ^ “Archaebacteria (Archaea) and the origin of the eukaryotic nucleus”. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8 (6): 630–7. (2005). doi:10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.004. PMID 16242992.

- ^ “Birth of the eukaryotes by a set of reactive innovations: New insights force us to relinquish gradual models”. BioEssays 37 (12): 1268–76. (2015). doi:10.1002/bies.201500107. PMID 26577075.

- ^ Bernstein H, Bernstein C. Sexual communication in archaea, the precursor to meiosis. pp. 103-117 in Biocommunication of Archaea (Guenther Witzany, ed.) 2017. Springer International Publishing ISBN 978-3-319-65535-2 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-65536-9