ヘファエスチン

| HEPH | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 識別子 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 記号 | HEPH, CPL, hephaestin, Hephaestin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 外部ID | OMIM: 300167 MGI: 1332240 HomoloGene: 32094 GeneCards: HEPH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| オルソログ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 種 | ヒト | マウス | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Entrez | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ensembl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UniProt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (タンパク質) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

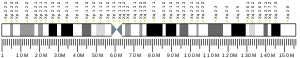

| 場所 (UCSC) | Chr X: 66.16 – 66.27 Mb | Chr X: 95.5 – 95.62 Mb | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PubMed検索 | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ウィキデータ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

ヘファエスチンもしくはヘファスチン(英: hephaestin、HEPH)は、ヒトではHEPH遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質である[5][6][7]。

機能[編集]

ヘファエスチンは鉄、そしておそらく銅の代謝と恒常性に関与している[8]。ヘファエスチンは銅依存性膜貫通型フェロキシダーゼであり、腸細胞から血液循環への鉄輸送を担う。ヘファエスチンは腸絨毛の細胞では側底膜に局在しているが、腸陰窩の細胞ではほとんど検出されない[9]。ヘファエスチンは鉄(II)イオン(Fe2+)を鉄(III)イオン(Fe3+)に変換し、側底膜に位置する鉄トランスポーターであるフェロポーチンとおそらく協働して鉄排出を媒介している。ヘファエスチンは結腸、脾臓、腎臓、乳房、胎盤、骨梁の細胞でも検出されるが、これらの組織における役割は確立されていない。ヘファエスチンは、銅の解毒と貯蔵に関与する血清デヒドロゲナーゼタンパク質であるセルロプラスミンとの相同性がみられる[10]。

ヘファエスチンは1158アミノ酸からなる前駆体から形成される1135アミノ酸のタンパク質で、130.4 kDaである。単量体当たり、6個の銅イオンを結合することが予測されている[11]。

発見[編集]

ヘファエスチンは1999年にカリフォルニア大学バークレー校のChristopher D. Vulpeらによって初めて同定された[6]。この新たに見つかったタンパク質は、ギリシア神話の鍛冶の神であるヘーパイストス(Hephaestus)から命名された。

ヘファエスチンに関する知見の多くは、マウスの鉄代謝の遺伝的変異に関する研究から得られたものである。ヘファエスチンはsla(sex-linked anemia)マウスの研究から同定された。このマウスは粘膜からの鉄分の取り込みは正常であるものの、腸細胞から血液循環への輸送に欠陥がみられる。slaマウスではHeph遺伝子の部分的欠失により、194アミノ酸分切り詰められたタンパク質の発現が引き起こされる。この切り詰められたヘファエスチンタンパク質は、検出と定量が可能な最低限度のフェロキシダーゼ活性を維持していることが研究から示唆されている[11]。このことから、sla表現型でみられる鉄排出の低下には代替的因子が寄与している可能性が生じている。

タンパク質の切り詰めに加え、鉄欠乏sla表現型はヘファエスチンの細胞内局在の変化によって説明される可能性もある。野生型のヘファエスチンは核周囲と側底膜に局在している[12]。対照的に、sla型ヘファエスチン核周囲にのみ局在し、側底膜にはほとんど検出されない[13]。ヘファエスチンの機能が側底膜を介した鉄の排出であることを考えると、この局在の変化はslaマウスでみられる腸での鉄の蓄積と全身的な鉄欠乏の説明となる可能性がある。

推定膜貫通ドメインを欠いたヒトヘファエスチンは、2005年にブリティッシュコロンビア大学のTanya Griffithsらによって初めて組換え発現が行われた[14]。この組換えヒトヘファエスチン(rhHp)は銅を結合していることが誘導結合プラズマ質量分析を用いて明らかにされ、セルロプラスミンなど他の青色マルチ銅オキシダーゼと同じく約610 nmに最大吸光を示した。硫酸アンモニウム鉄(II)を基質として用いた活性測定によって、rhHpのFe(II)に対するフェロキシダーゼ活性のKMは2.1 μMであることが示された。

構造[編集]

ヘファエスチンは、哺乳類のセルロプラスミン、酵母のFet3やFet5、細菌のアスコルビン酸オキシダーゼなどともに、銅オキシダーゼファミリーを構成する。ヘファエスチンと血清タンパク質セルロプラスミンのアミノ酸配列は50%同一であるが、ヘファエスチンのC末端には膜貫通ドメインと短い細胞質テールをコードする86アミノ酸からなる配列が含まれている[15]。セルロプラスミンの構造や反応速度論は広く研究が行われているが[16]、ヘファエスチンに関する研究はまだ同じレベルには達していない。セルロプラスミンに関する結晶学的データを用いてヘファエスチン構造の比較モデルが作製されており、こうした研究からヘファエスチンの酵素機能に重要な構造的特徴の多くがセルロプラスミンとの間で保存されていることが示唆されている。特に、ジスルフィド結合の形成に関与するシステイン残基、銅の結合に関与するヒスチジン残基、基質である鉄の結合に関与する残基は共通である[17]。

調節[編集]

ヘファエスチンの発現調節や、鉄の代謝や恒常性といったより大局的観点におけるヘファエスチンの役割に関しては、活発な研究が続いている領域である。一部の研究では、鉄分の摂取や貯蔵が十分な場合にはDMT1、フェロポーチン(IREG1)、ヘファエスチンのダウンレギュレーションが引き起こされ、腸細胞から血液循環への鉄の吸収が最小化される、という腸における鉄輸送の局所的・全身的制御機構が示唆されている。逆に、鉄分の摂取や貯蔵が少ない場合にはこれらがアップレギュレーションされ、腸細胞における鉄分の摂取と血液循環への輸送能力が高まる[18]。

生物学や疾患との関係[編集]

ヘファエスチンとヒトの疾患との関係はまだ示されていない。一方マウスモデルでは、ヘファエスチンの腸特異的ノックアウトと全身でのノックアウトはどちらも同様に十二指腸の腸細胞で重度な鉄蓄積を引き起こす一方、小球性・低色素性貧血が生じることから全身的には鉄欠乏が引き起こされていることが示されている。両系統で表現型が共通していることは、全身的な鉄恒常性の維持に腸のヘファエスチンが重要な役割を果たしていることを示唆している。しかしながら、どちらの系統も生存可能であるため、ヘファエスチンは生存に必要不可欠ではなく、生存を維持する他の補償機構が存在している可能性が高い[19]。

腸から血液循環の鉄輸送に加えて、フェロキシダーゼは網膜細胞からの鉄排出の促進にも重要な役割を果たしているようである。ヘファエスチンやセルロプラスミンそれぞれ単独の欠損では網膜への鉄蓄積は生じないようであるが、両者を共に欠損した場合には加齢に伴う網膜色素上皮の肥厚や網膜への鉄の蓄積といった、黄斑変性と一致する特徴が引き起こされることがマウスモデルでの研究から示唆されている[20]。ヘファエスチンはマウスやヒトの網膜色素上皮細胞、ラットのミュラー細胞株であるrMC-1細胞でも検出されており、ミュラー細胞では内境界膜に隣接した終足(endfoot)で最も高い発現がみられる[21]。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000089472 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031209 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ Ishikawa K, Nagase T, Suyama M, Miyajima N, Tanaka A, Kotani H, Nomura N, Ohara O (June 1998). “Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. X. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which can code for large proteins in vitro”. DNA Res. 5 (3): 169–76. doi:10.1093/dnares/5.3.169. PMID 9734811.

- ^ a b Vulpe CD, Kuo YM, Murphy TL, Cowley L, Askwith C, Libina N, Gitschier J, Anderson GJ (February 1999). “Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse”. Nat. Genet. 21 (2): 195–9. doi:10.1038/5979. PMID 9988272.

- ^ “Entrez Gene: Hephaestin”. 2023年2月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Decreased hephaestin activity in the intestine of copper-deficient mice causes systemic iron deficiency”. J. Nutr. 136 (5): 1236–41. (May 2006). doi:10.1093/jn/136.5.1236. PMID 16614410.

- ^ Hudson, David M.; Curtis, Susan B.; Smith, Valerie C.; Griffiths, Tanya A. M.; Wong, Ann Y. K.; Scudamore, Charles H.; Buchan, Alison M. J.; MacGillivray, Ross T. A. (2010-03). “Human hephaestin expression is not limited to enterocytes of the gastrointestinal tract but is also found in the antrum, the enteric nervous system, and pancreatic {beta}-cells”. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 298 (3): G425–432. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00453.2009. ISSN 1522-1547. PMID 20019163.

- ^ Wang, Ya-Fang; Zhang, Jie; Su, Yi; Shen, Yan-Yan; Jiang, Dong-Xian; Hou, Ying-Yong; Geng, Mei-Yu; Ding, Jian et al. (2017-08-17). “G9a regulates breast cancer growth by modulating iron homeostasis through the repression of ferroxidase hephaestin”. Nature Communications 8 (1): 274. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00350-9. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5561105. PMID 28819251.

- ^ a b c “Hephaestin is a ferroxidase that maintains partial activity in sex-linked anemia mice”. Blood 103 (10): 3933–9. (May 2004). doi:10.1182/blood-2003-09-3139. PMID 14751926.

- ^ C. N. Roy; C. A. Enns (December 2000). “Iron homeostasis: new tales from the crypt”. Blood 96 (13): 4020–4027. doi:10.1182/blood.V96.13.4020. PMID 11110669.

- ^ a b Y. M. Kuo; T. Su; H. Chen; Z. Attieh; B. A. Syed; A. T. McKie; G. J. Anderson; J. Gitschier et al. (February 2004). “Mislocalisation of hephaestin, a multicopper ferroxidase involved in basolateral intestinal iron transport, in the sex linked anaemia mouse”. Gut 53 (2): 201–206. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.019026. PMC 1774920. PMID 14724150.

- ^ “Recombinant expression and functional characterization of human hephaestin: a multicopper oxidase with ferroxidase activity”. Biochemistry 44 (45): 14725–31. (November 2005). doi:10.1021/bi051559k. hdl:2429/18540. PMID 16274220.

- ^ Jiri Petrak; Daniel Vyoral (June 2005). “Hephaestin--a ferroxidase of cellular iron export”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 37 (6): 1173–1178. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2004.12.007. PMID 15778082.

- ^ P. Bielli; L. Calabrese (September 2002). “Structure to function relationships in ceruloplasmin: a 'moonlighting' protein”. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 59 (9): 1413–1427. doi:10.1007/s00018-002-8519-2. PMID 12440766.

- ^ Basharut A. Syed; Nick J. Beaumont; Alpesh Patel; Claire E. Naylor; Henry K. Bayele; Christopher L. Joannou; Peter S. N. Rowe; Robert W. Evans et al. (March 2002). “Analysis of the human hephaestin gene and protein: comparative modelling of the N-terminus ecto-domain based upon ceruloplasmin”. Protein Engineering 15 (3): 205–214. doi:10.1093/protein/15.3.205. PMID 11932491.

- ^ a b Huijun Chen; Trent Su; Zouhair K. Attieh; Tama C. Fox; Andrew T. McKie; Gregory J. Anderson; Chris D. Vulpe (September 2003). “Systemic regulation of Hephaestin and Ireg1 revealed in studies of genetic and nutritional iron deficiency”. Blood 102 (5): 1893–1899. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-02-0347. PMID 12730111.

- ^ Brie K. Fuqua; Yan Lu; Deepak Darshan; David M. Frazer; Sarah J. Wilkins; Natalie Wolkow; Austin G. Bell; JoAnn Hsu et al. (2014). “The multicopper ferroxidase hephaestin enhances intestinal iron absorption in mice”. PLoS ONE 9 (6): e98792. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...998792F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098792. PMC 4045767. PMID 24896847.

- ^ Paul Hahn; Ying Qian; Tzvete Dentchev; Lin Chen; John Beard; Zena Leah Harris; Joshua L. Dunaief (September 2004). “Disruption of ceruloplasmin and hephaestin in mice causes retinal iron overload and retinal degeneration with features of age-related macular degeneration”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (38): 13850–13855. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10113850H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405146101. PMC 518844. PMID 15365174.

- ^ Xining He; Paul Hahn; Jared Iacovelli; Robert Wong; Chih King; Robert Bhisitkul; Mina Massaro-Giordano; Joshua L. Dunaief (November 2007). “Iron homeostasis and toxicity in retinal degeneration”. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 26 (6): 649–673. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.07.004. PMC 2093950. PMID 17921041.