アンフィレグリン

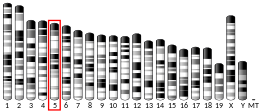

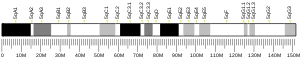

アンフィレグリン(英: amphiregulin、略称: AREG)は、252アミノ酸からなる膜貫通型糖タンパク質として合成されるタンパク質であり、ヒトではAREG遺伝子にコードされる[5][6][7][8]。

生物学的役割[編集]

アンフィレグリンは、上皮成長因子(EGF)ファミリーに属するタンパク質である[5]。

アンフィレグリンはエストロゲンの作用や、乳管の発生に重要な因子であり[9][10][11][12][13]、アンフィレグリンノックアウトマウスでは乳管の発生がみられない[12]。この表現型はEGFRやERαのノックアウトマウスと類似しており、これらのマウスでも乳管の成長はみられない[12]。アンフィレグリンは、卵巣、胎盤、膵臓、乳房、肺、脾臓など多くの部位で発現している。アンフィレグリンの発現は、TGF-α、TNF-α、IL-1、プロスタグランジンによって誘導される[14][15]。

臨床的意義[編集]

炎症[編集]

アンフィレグリンは2型炎症応答の一部を構成している[16]。アンフィレグリンの産生源となる細胞は2型自然リンパ球(ILC2)であり、発現はインターロイキン-33(IL-33)に依存している。ILC2は腸の組織損傷とIL-33による活性化の後にアンフィレグリンを発現する。さらにマウスでは、Tリンパ球が正常数のマウスと枯渇マウスの双方において、内在性のAREGがIL-33とともに腸の炎症を軽減することが報告されている[17]。

組織修復における役割[編集]

一般的に、アンフィレグリンは2型炎症応答を介したレジスタンスとトレランスの一部を構成していると考えられており、トレランスは急性・慢性炎症損傷後の組織の完全性の再確立の促進によるものである。アンフィレグリンの組織修復への関与は、分裂促進シグナルを誘導し、また上皮細胞の分化をもたらす、という二重の役割によって説明される[18]。

上皮由来のアンフィレグリンは組織修復を促進し、またいくつかの免疫細胞も組織損傷時にアンフィレグリンを発現することが知られている。このように、アンフィレグリンは免疫細胞と上皮細胞のクロストークの一部を構成している[18][19]。

組織損傷後にアンフィレグリンの発現が上昇することが知られている免疫細胞集団としては、ILC2が挙げられる。この現象は、肺、腸、皮膚などいくつかの器官で観察されている。ILC2によるアンフィレグリンの発現は、IL-33によって誘導される[20]。また皮膚由来のILC2では、アンフィレグリンの発現はKLRG1とE-カドヘリンとの相互作用によって調節されている[21]。腸の損傷後、活性化された腸ILC2はアンフィレグリンを産生し、それによって上皮細胞によるムチン産生を増加させ、また杯細胞のクローディン1の発現上昇によって活性を高める。こうしたアンフィレグリンの機能は粘液層を強化し、またジャンクションの強度を高める役割を果たす[20]。

組織常在型の制御性T細胞(Treg)もアンフィレグリンを発現して組織修復を促進する。これらの細胞は異なるT細胞受容体(TCR)レパートリーを有しているため、アンフィレグリンの産生にTCRシグナルは必要ではないようである。一方で、この過程はIL-33/ST2経路とインターロイキン-18受容体の発現に依存している場合がある[22]。また、こうしたTregが発現するアンフィレグリンによってこれらの細胞の機能はさらに高まり、自己分泌によるポジティブフィードバックループが形成される[23]。アンフィレグリンを発現する組織常在型Tregは肺で観察されており、その大部分はCD44hiCD62Llo集団である。また、CD103、PD-1、GITR、CTLA-4、KLRG1を高レベルで発現している[22]。こうした細胞集団は損傷した筋肉でも見つかっており、好酸球の流入と関係している。アンフィレグリンの産生は骨格筋の衛星細胞のコロニー形成能や筋肉への分化を高め、筋修復を高めている可能性がin vitroで示されている[18]。炎症を起こした結腸では、Gata3+Helios+ Tregが高レベルのアンフィレグリンを発現する[24]。また、アンフィレグリン発現Tregは、KGF、CD39、CD73とともに実質細胞に作用し、組織修復と再生を促進する[22]。

一部の自然免疫型T細胞(unconventional T細胞)も、アンフィレグリンによる組織修復に対して直接的または間接的に関係している。腸の損傷後、MAIT細胞はアンフィレグリンを産生し、上皮細胞のターンオーバーと杯細胞の活性亢進をもたらす。また、IL-33シグナルに依存してILC2やTregから産生されるアンフィレグリンによる修復促進応答は、IL17Aを産生するγδT細胞によって誘導される。こうしたIL17A産生γδT細胞とアンフィレグリンとの関係は、肺や口腔粘膜で観察されている[20]。

乾癬[編集]

アンフィレグリンをコードするAREG遺伝子の変異は、乾癬様の皮膚表現型と関係している[5][25]。血中アンフィレグリン濃度の高さは、急性移植片対宿主病(aGVHD)の進行と関係している[26][27][28]。

がん[編集]

アンフィレグリンの過剰発現は、乳がん、前立腺がん、結腸がん、膵臓がん、肺がん、脾臓腫瘍、膀胱がんと関係している[29][30][31]。

関節リウマチ[編集]

関節リウマチにおいては、アンフィレグリンの発現は線維芽細胞の増殖や、炎症性サイトカインであるインターロイキン-8、血管内皮細胞増殖因子(VEGF)の産生と関係しているようである[32]。

線維症[編集]

いくつかの器官では、アンフィレグリン濃度の慢性的上昇は線維化と関係している。ILC2は肝臓、皮膚、肺の線維化を駆動する因子であり、ILC2によるインターロイキン-13(IL-13)とアンフィレグリンの発現がこの過程に関与していることが示唆されている[18]。アンフィレグリンを発現する病原性メモリーTh2細胞も肺線維症に関与している。ヒョウヒダニ(チリダニ)への曝露は、アンフィレグリン発現病原性メモリーTh2細胞の増加をもたらす。この現象はIL-33/ST2シグナルと関係している可能性があり、この経路を遮断することでアンフィレグリンの産生は低下する。気道の線維化におけるアンフィレグリンの機能は、アンフィレグリンの結合標的であるEGFRを発現する好酸球と関係しており、オステオポンチンなど炎症性遺伝子のアップレギュレーションが引き起こされる。好酸球によるオステオポンチンの発現は、肺線維症発症の原因となる[33]。さらに、マクロファージ由来のアンフィレグリンはTGF-β誘発性の線維化にも関与しており、インテグリンαV複合体の活性化を介して潜在型TGF-βを活性化することが示されている[18][34][35]。肝臓では、継続的な壊死によって肝ILC2の活性化が引き起こされ、IL-13とアンフィレグリンが放出される。その結果、肝星細胞が活性化されて筋線維芽細胞への形質転換が引き起こされ、最終的には肝線維化が促進される[21]。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000109321 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029378 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ a b c “Entrez Gene: AREG amphiregulin (schwannoma-derived growth factor)”. 2023年8月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Structure and function of human amphiregulin: a member of the epidermal growth factor family”. Science 243 (4894 Pt 1): 1074–1076. (February 1989). Bibcode: 1989Sci...243.1074S. doi:10.1126/science.2466334. PMID 2466334.

- ^ “The amphiregulin gene encodes a novel epidermal growth factor-related protein with tumor-inhibitory activity”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 10 (5): 1969–1981. (May 1990). doi:10.1128/MCB.10.5.1969. PMC 360543. PMID 2325643.

- ^ “AREG (amphiregulin (schwannoma-derived growth factor))”. atlasgeneticsoncology.org. 2019年8月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Amphiregulin mediates progesterone-induced mammary ductal development during puberty”. Breast Cancer Research 15 (3): R44. (May 2013). doi:10.1186/bcr3431. PMC 3738150. PMID 23705924.

- ^ “Estrogen regulation of mammary gland development and breast cancer: amphiregulin takes center stage”. Breast Cancer Research 9 (4): 304. (2007). doi:10.1186/bcr1740. PMC 2206713. PMID 17659070.

- ^ “Amphiregulin mediates estrogen, progesterone, and EGFR signaling in the normal rat mammary gland and in hormone-dependent rat mammary cancers”. Hormones & Cancer 1 (5): 229–244. (October 2010). doi:10.1007/s12672-010-0048-0. PMC 3000471. PMID 21258428.

- ^ a b c “Amphiregulin: role in mammary gland development and breast cancer”. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia 13 (2): 159–169. (June 2008). doi:10.1007/s10911-008-9075-7. PMID 18398673.

- ^ “The ADAM17-amphiregulin-EGFR axis in mammary development and cancer”. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia 13 (2): 181–194. (June 2008). doi:10.1007/s10911-008-9084-6. PMC 2723838. PMID 18470483.

- ^ “AREG (amphiregulin (schwannoma-derived growth factor))”. atlasgeneticsoncology.org. 2019年8月27日閲覧。

- ^ “The multiple roles of amphiregulin in human cancer”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1816 (2): 119–131. (December 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.05.003. PMID 21658434.

- ^ “Amphiregulin, a TH2 cytokine enhancing resistance to nematodes”. Science 314 (5806): 1746. (December 2006). Bibcode: 2006Sci...314.1746Z. doi:10.1126/science.1133715. PMID 17170297.

- ^ “IL-33 promotes an innate immune pathway of intestinal tissue protection dependent on amphiregulin-EGFR interactions”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (34): 10762–10767. (August 2015). Bibcode: 2015PNAS..11210762M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509070112. PMC 4553775. PMID 26243875.

- ^ a b c d e “Emerging functions of amphiregulin in orchestrating immunity, inflammation, and tissue repair”. Immunity 42 (2): 216–226. (February 2015). doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.020. PMC 4792035. PMID 25692699.

- ^ “Amphiregulin in cellular physiology, health, and disease: Potential use as a biomarker and therapeutic target”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 237 (2): 1143–1156. (February 2022). doi:10.1002/jcp.30615. PMID 34698381.

- ^ a b c “Maintenance of Barrier Tissue Integrity by Unconventional Lymphocytes”. Frontiers in Immunology 12: 670471. (2021). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.670471. PMC 8079635. PMID 33936115.

- ^ a b “Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Liver and Gut: From Current Knowledge to Future Perspectives”. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20 (8): 1896. (April 2019). doi:10.3390/ijms20081896. PMC 6514972. PMID 30999584.

- ^ a b c “'Repair' Treg Cells in Tissue Injury”. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 43 (6): 2155–2169. (2017-10-25). doi:10.1159/000484295. PMID 29069643.

- ^ “Regulatory T cells in skin injury: At the crossroads of tolerance and tissue repair”. Science Immunology 5 (47). (May 2020). doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz9631. PMC 7274208. PMID 32358172.

- ^ “Tissue regulatory T cells and neural repair”. International Immunology 31 (6): 361–369. (May 2019). doi:10.1093/intimm/dxz031. PMID 30893423.

- ^ “Amphiregulin and epidermal hyperplasia: amphiregulin is required to maintain the psoriatic phenotype of human skin grafts on severe combined immunodeficient mice”. The American Journal of Pathology 166 (4): 1009–1016. (April 2005). doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62322-X. PMC 1780140. PMID 15793282.

- ^ “Amphiregulin and epidermal hyperplasia: amphiregulin is required to maintain the psoriatic phenotype of human skin grafts on severe combined immunodeficient mice”. The American Journal of Pathology 166 (4): 1009–1016. (April 2005). doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62322-X. PMC 1780140. PMID 15793282.

- ^ “Amphiregulin modifies the Minnesota Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Risk Score: results from BMT CTN 0302/0802”. Blood Advances 2 (15): 1882–1888. (August 2018). doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018017343. PMC 6093743. PMID 30087106.

- ^ “Overexpression of amphiregulin, a major autocrine growth factor for cultured human keratinocytes, in hyperproliferative skin diseases”. The American Journal of Dermatopathology 18 (2): 165–171. (April 1996). doi:10.1097/00000372-199604000-00010. PMID 8739992.

- ^ “The multiple roles of amphiregulin in human cancer”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1816 (2): 119–131. (December 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.05.003. PMID 21658434.

- ^ “AREG (amphiregulin (schwannoma-derived growth factor))”. atlasgeneticsoncology.org. 2019年8月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Amphiregulin: role in mammary gland development and breast cancer”. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia 13 (2): 159–169. (June 2008). doi:10.1007/s10911-008-9075-7. PMID 18398673.

- ^ “Proinflammatory role of amphiregulin, an epidermal growth factor family member whose expression is augmented in rheumatoid arthritis patients”. Journal of Inflammation 5: 5. (April 2008). doi:10.1186/1476-9255-5-5. PMC 2396620. PMID 18439312.

- ^ “The immunopathology of lung fibrosis: amphiregulin-producing pathogenic memory T helper-2 cells control the airway fibrotic responses by inducing eosinophils to secrete osteopontin”. Seminars in Immunopathology 41 (3): 339–348. (May 2019). doi:10.1007/s00281-019-00735-6. PMID 30968186.

- ^ “Macrophage amphiregulin-pericyte TGF-β axis: a novel mechanism of the immune system that contributes to wound repair”. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 52 (4): 463–465. (April 2020). doi:10.1093/abbs/gmaa001. PMID 32147698.

- ^ “Immune- and non-immune-mediated roles of regulatory T-cells during wound healing”. Immunology 157 (3): 190–197. (July 2019). doi:10.1111/imm.13057. PMC 6600083. PMID 30866049.

関連文献[編集]

- “Colorectum cell-derived growth factor (CRDGF) is homologous to amphiregulin, a member of the epidermal growth factor family”. Growth Factors 7 (3): 195–205. (1993). doi:10.3109/08977199209046924. PMID 1333777.

- “A heparin sulfate-regulated human keratinocyte autocrine factor is similar or identical to amphiregulin”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 11 (5): 2547–2557. (May 1991). doi:10.1128/MCB.11.5.2547. PMC 360024. PMID 2017164.

- “Structure, expression and function of a schwannoma-derived growth factor”. Nature 348 (6298): 257–260. (November 1990). Bibcode: 1990Natur.348..257K. doi:10.1038/348257a0. PMID 2234093.

- “The amphiregulin gene encodes a novel epidermal growth factor-related protein with tumor-inhibitory activity”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 10 (5): 1969–1981. (May 1990). doi:10.1128/MCB.10.5.1969. PMC 360543. PMID 2325643.

- “Structure and function of human amphiregulin: a member of the epidermal growth factor family”. Science 243 (4894 Pt 1): 1074–1076. (February 1989). Bibcode: 1989Sci...243.1074S. doi:10.1126/science.2466334. PMID 2466334.

- “Amphiregulin: a bifunctional growth-modulating glycoprotein produced by the phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-treated human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 85 (17): 6528–6532. (September 1988). Bibcode: 1988PNAS...85.6528S. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.17.6528. PMC 282006. PMID 3413110.

- “A mapping study of 13 genes on human chromosome bands 4q11→q25”. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 69 (3–4): 260–265. (1995). doi:10.1159/000133976. PMID 7698025.

- “Transgenic expression of the human amphiregulin gene induces a psoriasis-like phenotype”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 100 (9): 2286–2294. (November 1997). doi:10.1172/JCI119766. PMC 508424. PMID 9410906.

- “A differential requirement for the COOH-terminal region of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor in amphiregulin and EGF mitogenic signaling”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 (13): 8900–8909. (March 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.13.8900. PMID 10085134.

- “Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) regulates the expression of progelatinase B (MMP-9) in breast epithelial cells”. International Journal of Cancer 82 (2): 268–273. (July 1999). doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990719)82:2<268::AID-IJC18>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 10389762.

- “Production of epidermal growth factor related ligands in tumorigenic and benign human lung epithelial cells”. Cancer Letters 142 (1): 55–63. (July 1999). doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00166-4. PMID 10424781.

- “The Wilms tumor suppressor WT1 encodes a transcriptional activator of amphiregulin”. Cell 98 (5): 663–673. (September 1999). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80053-7. PMID 10490105.

- “Ectodomain shedding of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands is required for keratinocyte migration in cutaneous wound healing”. The Journal of Cell Biology 151 (2): 209–220. (October 2000). doi:10.1083/jcb.151.2.209. PMC 2192647. PMID 11038170.

- “Induction and expression of cyclin D3 in human pancreatic cancer”. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 127 (7): 449–454. (July 2001). doi:10.1007/s004320100235. PMID 11469683.

- “A functional screen for genes inducing epidermal growth factor autonomy of human mammary epithelial cells confirms the role of amphiregulin”. Oncogene 20 (30): 4019–4028. (July 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204537. PMID 11494130.

- “A subclass of HER1 ligands are prognostic markers for survival in bladder cancer patients”. Cancer Research 61 (16): 6227–6233. (August 2001). PMID 11507076.

- “T-cell receptor gamma chain alternate reading frame protein (TARP) expression in prostate cancer cells leads to an increased growth rate and induction of caveolins and amphiregulin”. Cancer Research 61 (22): 8122–8126. (November 2001). PMID 11719440.

- “mRNA expression of EGF receptor ligands in atrophic gastritis before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication”. Medical Science Monitor 8 (2): CR53–CR58. (February 2002). PMID 11859273.

- “Possible autocrine loop of the epidermal growth factor system in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia treated with finasteride: a placebo-controlled randomized study”. BJU International 89 (6): 583–590. (April 2002). doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02665.x. PMID 11942969.

- “Inhibition of apoptosis by amphiregulin via an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-dependent pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (51): 49127–49133. (December 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M207584200. PMID 12356750.