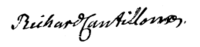

リチャード・カンティロン

この記事は英語版の対応するページを翻訳することにより充実させることができます。(2020年2月) 翻訳前に重要な指示を読むには右にある[表示]をクリックしてください。

|

リチャード・カンティロン(Richard Cantillon、? - 1734年)は、フランスの銀行家、実業家、経済思想家。

経歴[編集]

詳しい出自は不明だが、スペイン系のアイルランド人商人の息子として1680年から1690年の間に生まれたと言われている。その後フランスへ渡り、アイルランド系の銀行に勤務する。1717年に独立し、ジョン・ローの知遇を得る。ローがミシシッピ計画を企てた際にはその実現性について懐疑的であったが、それに伴うバブルで莫大な利益を得る。しかし、その事後処理をめぐって顧客との間で裁判沙汰になり、フランスを出国しアムステルダムへ赴く。その裁判にあたって、ローへの批判として著したのが代表的著作『商業試論』である。その後、ロンドンに移り住むが、同地で放火に遭い、焼死した。『商業試論』以外の手稿類は残っていない。

思想[編集]

カンティロンは、『商業試論』で土地はすべての物産と商品の素材であり、労働はその形式であると述べ、生産物の価値は詰まるところ土地の価値に還元する、とフランソワ・ケネーに先立って重農主義を主張した。その一方で、現金の増加はそれに比例した一国の消費の増大をひき起こし、それがしだいに価格の高騰を生むと、乗数効果による貨幣流通量のコントロールの必要性についても言及し、それを元に重商主義の主張の一つである貿易差額主義を支持している。

カンティロンの主張は、価値論において重農主義的であるものの、本来的な価値と市場における価格との乖離にも着目し、その乖離を利潤機会として追求する存在として企業者の存在を定義している。そして、企業者と顧客が市場で「掛け合い」をすることで、市場における均衡状態が実現すると結論付けている。

影響[編集]

『商業試論』は、1730年から32年のあいだに英語で執筆されたと見られるが、カンティロンの生前は公刊されなかった。しかし、カンティロン自身による仏訳の手稿を閲読したミラボー侯爵とヴァンサン・ド・グルネーの理論形成に影響をおよぼした。その後1755年にようやく仏訳が出版されたが、1756年にミラボー侯爵の『人間の友』、また1758年にケネーの『経済表』という重農主義の代表的著作が続いて出版され、『商業試論』は、それらに埋没してしまった。

『商業試論』は、1881年にジェヴォンズよって「経済学の揺籃」と評価され、あらためて知られるようになった[1]。

著作の邦訳[編集]

- 『商業試論』津田内匠訳、名古屋大学出版会、1992年

脚注[編集]

- ^ 津田内匠『商業試論』解説、232-3頁

参考文献[編集]

- 『創設者の経済学 ペティー・カンティロン・ケネー研究』渡辺輝雄著、未来社、1961年