「ZMapp」の版間の差分

編集の要約なし |

Atami wiki (会話 | 投稿記録) 編集の要約なし タグ: サイズの大幅な増減 |

||

| 19行目: | 19行目: | ||

[[Category:抗ウイルス薬]] |

[[Category:抗ウイルス薬]] |

||

[[Category:バイオテクノロジー]] |

[[Category:バイオテクノロジー]] |

||

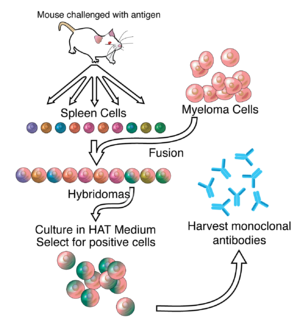

[[Image:Monoclonals.png|300px|thumb|right|Schematic representation of how monoclonal antibodies are generally made from [[hybridoma]]s. To make ZMapp, the genes encoding for the antibodies were extracted from the hybridomas, [[genetic engineering|genetically engineered]] to replace mouse components with human components, and [[transfected]] into tobacco plants.<ref name=Kroll/>]] |

|||

'''ZMapp''' is an experimental [[biopharmaceutical]] drug comprising three [[chimeric antibody|chimeric]] [[monoclonal antibody|monoclonal antibodies]] under development as a treatment for [[Ebola virus disease]]. The drug was first tested in humans during the [[2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak]], but has not been subjected to a [[randomized controlled trial]] to determine whether it works, and whether it is safe enough to allow on the market. |

|||

==Medical use== |

|||

ZMapp is under development as a treatment for [[Ebola virus disease]].<ref name=Nature2014/> It was first used experimentally to treat some people with Ebola virus disease during the [[2014 West African Ebola outbreak]], but as of August 2014 it had not yet been tested in a [[clinical trial]] to support widespread usage in humans; it is not known whether it is effective to treat the disease, nor if it is safe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/news/20140812/who-experts-give-nod-to-using-untested-ebola-drugs|title=WHO Experts Give Nod to Using Untested Ebola Drugs|date=August 12, 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/ethical-considerations/en/|title=WHO – Ethical considerations for use of unregistered interventions for Ebola virus disease|publisher=[[World Health Organization]]|accessdate=8 October 2014}}</ref><ref name=forbes2/> |

|||

==Mechanism of action== |

|||

Like [[intravenous immunoglobulin]] therapy, ZMapp contains [[neutralizing antibodies]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/ebola-cocktail-developed-at-canadian-and-u-s-labs-1.2727703|title=Ebola 'cocktail' developed at Canadian and U.S. labs|publisher=CBC News|date=2014-08-05}}</ref> that provide [[passive immunity]] to the virus by directly and specifically reacting with it in a "[[lock and key model|lock and key]]" fashion.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Keller MA, Stiehm ER |title=Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases |journal=Clin. Microbiol. Rev. |volume=13 |issue=4 |pages=602–14 | date=October 2000 |pmid=11023960 |pmc=88952 |doi=10.1128/CMR.13.4.602-614.2000}}</ref> |

|||

==Physical and chemical properties== |

|||

The drug is composed of three [[monoclonal antibody|monoclonal antibodies]] (mAbs) that have been [[chimeric antibody|chimerized]] by [[genetic engineering]].<ref name = NYT>{{cite news |last= Pollack|first= Andrew|date= 29 August 2014|title= Experimental Drug Would Help Fight Ebola if Supply Increases, Study Finds|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/world/africa/study-says-zmapp-works-against-ebola-but-making-it-takes-time.html?_r=0|newspaper= [[The New York Times]]|accessdate= 1 September 2014}}</ref> The components are chimeric monoclonal antibody c13C6 from a previously existing antibody cocktail called "MB-003" and two chimeric mAbs from a different antibody cocktail called ZMab, c2G4 and c4G7.<ref name=Nature2014/> |

|||

ZMapp is manufactured in the tobacco plant ''[[Nicotiana benthamiana]]'' in the [[bioproduction]] process known as "[[pharming (genetics)|pharming]]" by Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of [[Reynolds American]].<ref name=Kroll/><ref>{{cite news|first=Lois|last= Parshley|newspaper=[[Popular Science]]|date=8 August 2014|url=http://www.popsci.com/article/science/zmapp-experimental-ebola-treatment-explained| title=ZMapp: The Experimental Ebola Treatment Explained}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|first=Fran|last=Daniel|newspaper=[[Winston-Salem Journal]]|date=12 August 2014|url=http://www.journalnow.com/news/local/ebola-drug-provided-for-two-americans-by-reynolds-american-subsidiary/article_144fb3ce-1cb3-11e4-9f1b-0017a43b2370.html|title=Ebola drug provided for two Americans by Reynolds American subsidiary}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Agroinfiltration.jpg|thumb|ALT=green plant being injected by a needle|The ''[[Nicotiana benthamiana]]'' tobacco plant]] |

|||

==History== |

|||

The composite drug is being developed by [[Leaf Biopharmaceutical]] (LeafBio, Inc.), a San Diego based arm of [[Mapp Biopharmaceutical]].<ref>{{official website |date=15 July 2014 |url=http://www.leafbio.com/zmab.pdf |title=Monoclonal antibody-based filovirus therapeutic licensed to Leaf Biopharmaceutical}}</ref> LeafBio created ZMapp in collaboration with its parent and [[Defyrus Inc.]], each of which had developed its own cocktail of antibodies, called MB-003 and ZMab. |

|||

===MB-003=== |

|||

MB-003 is a cocktail of three humanized or human–mouse chimeric mAbs: c13C6, h13F6 and c6D8.<ref name=Nature2014/> A study published in September 2012 found that [[rhesus macaques]] infected with [[Ebola virus]] (EBOV) survived when receiving MB-003 (mixture of 3 chimeric monoclonal antibodies) one hour after infection. When treated 24 or 48 hours after infection, four of six animals survived and had little to no [[viremia]] and few, if any, clinical symptoms.<ref name=Zeitlin2012>{{cite journal |author=Olinger GG, Pettitt J, Kim D, ''et al.'' |title=Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=109 |issue=44 |pages=18030–5 |date=October 2012 |pmid=23071322 |pmc=3497800 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1213709109}}</ref> |

|||

MB-003 was created by [[Mapp Biopharmaceutical]], based in San Diego, with years of funding from US government agencies including the [[National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease]], [[Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority]], and the [[Defense Threat Reduction Agency]].<ref name=Kroll>{{cite news |first=David |last=Kroll |publisher=Forbes |date=5 August 2014|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2014/08/05/ebola-secret-serum-small-biopharma-the-army-and-big-tobacco/ |title=Ebola 'Secret Serum': Small Biopharma, The Army, And Big Tobacco}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=29 August 2014 |url=http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/guinea/qa-experimental-treatments.html |title=Questions and answers on experimental treatments and vaccines for Ebola}}</ref> |

|||

===ZMAb=== |

|||

ZMAb is a mixture of three mouse mAbs: m1H3, m2G4 and m4G7.<ref name=Nature2014/> A study published in November 2013 found that EBOV-infected [[macaque]] monkeys survived after being given a therapy with a combination of three EBOV surface [[glycoprotein]] (EBOV-GP)-specific monoclonal antibodies (ZMAb) within 24 hours of infection. The authors concluded that post-exposure treatment resulted in a robust immune response, with good protection for up to 10 weeks and some protection at 13 weeks.<ref name=ZMAbStudy>{{cite journal |author=Qiu X, Audet J, Wong G, ''et al.'' |title=Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb |journal=Sci Rep |volume=3 |issue= |pages=3365 |year=2013 |pmid=24284388 |pmc=3842534 |doi=10.1038/srep03365}}</ref> |

|||

ZMab was created by Defyrus, a Toronto-based [[biodefense]] company, funded by the [[Public Health Agency of Canada]].<ref name=Branswell>{{cite news|first=Helen |last=Branswell|publisher=Canadian Press|date=5 August 2014|url=http://www.brandonsun.com/business/breaking-news/experimental-ebola-drug-based-on-research-discoveries-from-canadas-national-lab-269910211.html|title=Experimental Ebola drug based on research discoveries from Canada's national lab}}</ref> The identification of the optimal components from MB-003 and ZMab was carried out at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s [[National Microbiology Laboratory]] in Winnipeg.<ref name=Branswell2>{{cite news |first=Helen |last=Branswell |publisher=Macleans |agency=Canadian Press|date=29 August 2014 |url=http://www.macleans.ca/society/health/scientists-at-canadas-national-lab-created-tested-ebola-drug-zmapp/ |title=Scientists at Canada’s national lab created, tested Ebola drug ZMapp}}</ref> |

|||

===ZMapp=== |

|||

A 2014 paper described how Mapp and its collaborators, including investigators at [[Public Health Agency of Canada]], Kentucky BioProcessing, and the [[National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases]], first [[chimeric antibody|chimerized]] the three antibodies comprising ZMAb, then tested combinations of MB-003 and the chimeric ZMAb antibodies in guinea pigs and then primates to determine the best combination, which turned out to be c13C6 from MB-003 and two chimeric mAbs from ZMAb, c2G4 and c4G7. This is ZMapp.<ref name=Nature2014>{{cite journal |author=Qiu X, Wong G, Audet J, ''et al.'' |title=Reversion of advanced Ebola virus disease in nonhuman primates with ZMapp |journal=Nature |volume= 514|issue= 7520|pages= 47–53| date=August 2014 |pmid=25171469 |doi=10.1038/nature13777}}</ref> |

|||

In an experiment also published in the 2014 paper, 21 [[rhesus macaque]] primates were infected with the [[Kikwit]] Congolese variant of EBOV. Three primates in the control arm were given a non-functional antibody, and the 18 in the treatment arm were divided into three groups of six. All primates in the treatment arm received three doses of ZMapp, spaced 3 days apart. The first treatment group received its first dose on 3rd day after being infected; the second group on the 4th day after being infected, and the third group, on the 5th day after being infected. All three primates in the control group died; all 18 primates in the treatment arm survived.<ref name=Nature2014/> Mapp then went on to show that ZMapp inhibits replication of a Guinean strain of EBOV in cell cultures.<ref name=NatureNews2014>{{cite journal |author=Geisbert TW |title=Medical research: Ebola therapy protects severely ill monkeys |journal=Nature |volume= 514|issue= 7520|pages= 41–3| date=August 2014 |pmid=25171470 |doi=10.1038/nature13746}}</ref> |

|||

Mapp remains involved in the production of the drug through its contracts with Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of [[Reynolds American]].<ref name=Kroll/> To produce the drug, genes coding for the chimeric mAbs were inserted into [[viral vectors]], and tobacco plants are infected with the viral vector encoding for the antibodies, using ''[[Agrobacterium]]'' cultures.<ref>{{cite web|title=Magnifection – mass-producing drugs in record time |url=http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2008/08/16/magnifection-mass-producing-drugs-in-record-time/ |publisher=National Geographic|accessdate=11 September 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Whaley KJ et al. |title=Emerging antibody-based products |journal=Curr Top Microbiol Immunol |year=2014 |volume=375 |pages=107–26 |pmid=22772797 |doi=10.1007/82_2012_240}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Giritch A et al. |title=Rapid high-yield expression of full-size IgG antibodies in plants coinfected with noncompeting viral vectors |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci USA|year=2006 |volume=40 |pages=14701–14706 |pmid=16973752 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0606631103 |issue=40}}</ref> Subsequently, antibodies are extracted and purified from the plants. Once the genes encoding the chimeric mAbs are in hand, the entire tobacco production cycle is believed to take a few months.<ref name=NYTwho>{{cite news |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/health/in-ebola-outbreak-who-should-get-experimental-drug.html |date=8 August 2014 |newspaper=The New York Times |title=In Ebola outbreak, who should get experimental drug?|last=Pollack|first=Andrew}}</ref> The development of these production methods was funded by the U.S. [[DARPA|Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]] as part of its bio-defense efforts following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.<ref>{{cite news |first=Brian |last=Till |newspaper=New Republic |date=9 September 2014 |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/119376/ebola-drug-zmapp-darpa-program-could-get-it-africa |title=DARPA may have a way to stop Ebola in its tracks}}</ref><ref>Shannon Pettypiece for Bloomberg News. 23, October 2014. [http://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2014-10-23/cheney-in-post-911-era-may-be-to-thank-on-ebola-vaccine Cheney in Post 9/11 Era May Be to Thank on Ebola Vaccine]</ref> |

|||

==Use during the 2014 Ebola outbreak== |

|||

{{see also|2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak}} |

|||

The FDA allowed two drugs, ZMapp and an [[RNA interference]] drug called [[TKM-Ebola]], to be used in Americans who had contracted [[Ebola virus disease]].<ref name=NYTseconddrug>{{cite news |last=Pollack |first=Andrew |date=7 August 2014 |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/08/health/second-experimental-drug-allowed-for-treating-ebola.html?_r=0 |title=Second drug is allowed for treatment of Ebola |newspaper=The New York Times |accessdate=8 August 2014}}</ref> Other countries have similar programs to allow early access through [[named patient programs]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Helene S |title=EU Compassionate Use Programmes (CUPs): Regulatory Framework and Points to Consider before CUP Implementation |url=http://adisonline.com/pharmaceuticalmedicine/Fulltext/2010/24040/EU_Compassionate_Use_Programmes__CUPs___Regulatory.4.aspx |journal=Pharm Med |volume=24 |issue=4 |pages=223–229 |year=2010 |doi=10.1007/bf03256820}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | date=11 August 2014| url=http://www.firstwordpharma.com/node/1229585?tsid=17#axzz3GcsaJ2Xn |title=Spain imports US experimental Ebola drug to treat priest evacuated from Liberia with disease |work=First Word Pharma }}</ref> {{As of|2014|10}}, ZMapp had been used to treat 7 individuals infected with the Ebola virus.<ref>{{cite news|title=US signs contract with ZMapp maker to accelerate development of the Ebola drug|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5488|accessdate=9 October 2014|agency=BMJ|publisher=BMJ|date=2014}}</ref> Although some of them have recovered, the outcome is not considered to be [[Statistical significance|statistically significant]].<ref name=forbes2>{{cite web|title=How Will We Know If The Ebola Drugs Worked?|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2014/08/26/how-will-we-know-if-the-ebola-drugs-worked/|work=Forbes|accessdate=10 September 2014}}</ref> Mapp announced on August 11, 2014, that its supplies of ZMapp had been exhausted.<ref>{{cite news |title=Ebola test drug’s supply ‘exhausted’ after shipments to Africa, U.S. company says |author=Lenny M. Bernstein, Brady Dennis |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/ebola-test-drugs-supply-exhausted-after-shipments-to-africa-us-company-says/2014/08/11/020cefc0-2199-11e4-958c-268a320a60ce_story.html |newspaper=Washington Post |date=11 August 2014}}</ref> |

|||

===Controversy=== |

|||

The lack of drugs and unavailability of experimental treatment in the most affected regions of the West African Ebola virus outbreak spurred some controversy.<ref name=NYTwho/> The fact that the drug was first given to Americans and a European and not to Africans, according to the ''[[Los Angeles Times]]'', "provoked outrage, feeding into African perceptions of Western insensitivity and arrogance, with a deep sense of mistrust and betrayal still lingering over the exploitation and abuses of the colonial era".<ref name=LAtimes/> [[Salim S. Abdool Karim]], the director of an AIDS research center in South Africa, placed the issue in the context of the history of exploitation and abuses. Responding to a question on how people may have reacted if ZMapp and other drugs would have been used first on Africans, said, "It would have been the front-page screaming headline: 'Africans used as guinea pigs for American drug company’s medicine{{' "}}.<ref name=NYTwho/> |

|||

In early August, the World Health Organization called for convening a panel of medical authorities "to consider whether experimental drugs should be more widely released." In a statement, [[Peter Piot]] (co-discoverer of the Ebola virus); Jeremy Farrar, the director of the [[Wellcome Trust]]; and David Heymann of the Chatham House Center on Global Health Security, called for the release of experimental drugs for [[2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak|affected African nations]].<ref name=LAtimes>{{cite news |date=6 August 2014 |url=http://www.latimes.com/world/africa/la-fg-three-ebola-experts-release-drugs-20140806-story.html|last=Dixon|first=Robyn|title=Three leading Ebola experts call for release of experimental drug|newspaper=Los Angeles Times}}</ref> |

|||

At an August 6, 2014 press conference, [[Barack Obama]], the [[President of the United States]], was questioned regarding whether the cocktail should be fast-tracked for approval or be made available to sick patients outside of the United States. He responded, “I think we’ve got to let the science guide us. I don't think all the information's in on whether this drug is helpful."<ref>{{cite news|date=6 August 2014|url=http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/ebola-virus-outbreak/obama-premature-say-u-s-should-green-light-new-ebola-n174461|title=Obama: 'Premature' to say U.S. should green-light new Ebola drug |publisher=NBC News }}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{cmn|2| |

|||

* [[Brincidofovir]] |

|||

* [[Monoclonal antibody therapy]] |

|||

* [[Palivizumab]] |

|||

* [[Pre-clinical development]] |

|||

* [[TKM-Ebola]] |

|||

* [[VSV-EBOV]] |

|||

}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*[http://www.mappbio.com/ Website of Mapp Biopharmaceutical] |

|||

* [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/surviving-ebola.html NOVA episode "Surviving Ebola"] |

|||

* {{cite news|publisher=BBC Radio 4 |work=File on Four |title=Ebola |date=21 October 2014 |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04lq2yg|quote = at 24:24, Charles Arntzen, professor of molecular biology at Arizona State University says:" It was shortly after our major 9/11 event in the US and there was money available through the US army to begin to develop preventive technology in the event of a bio terrorism attack. One of the agents that they were very interested in was the Ebola virus." }} |

|||

{{Ebola}} |

|||

{{Engineered antibodies |state=collapsed}} |

|||

{{Monoclonals for infectious disease and toxins |state=collapsed}} |

|||

[[Category:Immunology]] |

|||

[[Category:Antivirals]] |

|||

[[Category:Monoclonal antibodies]] |

|||

[[Category:Drugs]] |

|||

[[Category:Biotechnology]] |

|||

[[Category:Molecular biology]] |

|||

[[Category:Medical research]] |

|||

[[Category:Ebola]] |

|||

2014年11月8日 (土) 15:11時点における版

この項目「ZMapp」は途中まで翻訳されたものです。(原文:en:ZMapp 07:02, 6 August 2014 UTC) 翻訳作業に協力して下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴、翻訳のガイドラインも参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2014年8月) |

ZMapp(ジーマップ。ズィーマップとも)[1]は、タバコの近縁種であるNicotiana benthamianaの葉の遺伝子へ組み込んで作られる、3種類のヒト化モノクローナル抗体を混合した抗エボラウイルス薬である[2][3]。2014年現在、サルに対する非臨床試験しか実施されていない未承認薬であるが、2014年8月4日に2人のエボラ出血熱患者に投与され、実験的な治療が行われた。その結果、2人とも症状が改善されるポジティブな結果を示した[4]。しかしながらその翌週ごろに投与された6名のうち2名は一定の効果を見せた後に容態悪化で死亡しており、死因が用法用量の不適切か副作用か病状悪化か患者の体力由来かなどの詳細なソースも不明であり、薬効については不透明のままである[5]。なお2名死者のうちスペイン人司祭は後期高齢者であった[6]。この薬は、米国のベンチャー企業、マップ・バイオファーマシューティカル社が開発中である[7]。

元々は生物兵器から身を守るために開発されたもので、国立衛生研究所や国防脅威削減局が開発を支援している[8]。

脚注

- ^ エボラ、欧州初の死者…新薬治療のスペイン司祭(読売新聞 2014年8月12日 同日閲覧)

- ^ Larry Zeitlin, James Pettitt, Corinne Scully, Natasha Bohorova, Do Kim, Michael Pauly, Andrew Hiatt, Long Ngo, Herta Steinkellner, Kevin J. Whaley, and Gene G. Olinger (2011). “Enhanced potency of a fucose-free monoclonal antibody being developed as an Ebola virus immunoprotectant”. PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108360108.

- ^ Gene Garrard Olinger Jr, James Pettitt, Do Kim, Cara Working, Ognian Bohorov, Barry Bratcher, Ernie Hiatt, Steven D. Hume, Ashley K. Johnson, Josh Morton, Michael Pauly, Kevin J. Whaley, Calli M. Lear, Julia E. Biggins, Corinne Scully, Lisa Hensley, and Larry Zeitlin (2012). “Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques”. PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.1213709109.

- ^ "Mystery Ebola virus serum manufactured by San Diego firm". Los Angeles Times. August 4, 2014.

- ^ エボラ出血熱:未承認薬投与の医師死亡 リベリア 毎日新聞 2014年8月25日

- ^ エボラ熱感染のスペイン人神父、マドリードの病院で死亡 ロイター 2014年8月12日

- ^ http://medicalware.org/wiki/ZMapp

- ^ “実験用エボラ治療剤「ZMapp」、生体武器防御目的で開発”. 中央日報. (2014年8月6日) 2014年11月1日閲覧。

関連項目

ZMapp is an experimental biopharmaceutical drug comprising three chimeric monoclonal antibodies under development as a treatment for Ebola virus disease. The drug was first tested in humans during the 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak, but has not been subjected to a randomized controlled trial to determine whether it works, and whether it is safe enough to allow on the market.

Medical use

ZMapp is under development as a treatment for Ebola virus disease.[2] It was first used experimentally to treat some people with Ebola virus disease during the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak, but as of August 2014 it had not yet been tested in a clinical trial to support widespread usage in humans; it is not known whether it is effective to treat the disease, nor if it is safe.[3][4][5]

Mechanism of action

Like intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, ZMapp contains neutralizing antibodies[6] that provide passive immunity to the virus by directly and specifically reacting with it in a "lock and key" fashion.[7]

Physical and chemical properties

The drug is composed of three monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that have been chimerized by genetic engineering.[8] The components are chimeric monoclonal antibody c13C6 from a previously existing antibody cocktail called "MB-003" and two chimeric mAbs from a different antibody cocktail called ZMab, c2G4 and c4G7.[2]

ZMapp is manufactured in the tobacco plant Nicotiana benthamiana in the bioproduction process known as "pharming" by Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of Reynolds American.[1][9][10]

History

The composite drug is being developed by Leaf Biopharmaceutical (LeafBio, Inc.), a San Diego based arm of Mapp Biopharmaceutical.[11] LeafBio created ZMapp in collaboration with its parent and Defyrus Inc., each of which had developed its own cocktail of antibodies, called MB-003 and ZMab.

MB-003

MB-003 is a cocktail of three humanized or human–mouse chimeric mAbs: c13C6, h13F6 and c6D8.[2] A study published in September 2012 found that rhesus macaques infected with Ebola virus (EBOV) survived when receiving MB-003 (mixture of 3 chimeric monoclonal antibodies) one hour after infection. When treated 24 or 48 hours after infection, four of six animals survived and had little to no viremia and few, if any, clinical symptoms.[12]

MB-003 was created by Mapp Biopharmaceutical, based in San Diego, with years of funding from US government agencies including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency.[1][13]

ZMAb

ZMAb is a mixture of three mouse mAbs: m1H3, m2G4 and m4G7.[2] A study published in November 2013 found that EBOV-infected macaque monkeys survived after being given a therapy with a combination of three EBOV surface glycoprotein (EBOV-GP)-specific monoclonal antibodies (ZMAb) within 24 hours of infection. The authors concluded that post-exposure treatment resulted in a robust immune response, with good protection for up to 10 weeks and some protection at 13 weeks.[14]

ZMab was created by Defyrus, a Toronto-based biodefense company, funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.[15] The identification of the optimal components from MB-003 and ZMab was carried out at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg.[16]

ZMapp

A 2014 paper described how Mapp and its collaborators, including investigators at Public Health Agency of Canada, Kentucky BioProcessing, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, first chimerized the three antibodies comprising ZMAb, then tested combinations of MB-003 and the chimeric ZMAb antibodies in guinea pigs and then primates to determine the best combination, which turned out to be c13C6 from MB-003 and two chimeric mAbs from ZMAb, c2G4 and c4G7. This is ZMapp.[2]

In an experiment also published in the 2014 paper, 21 rhesus macaque primates were infected with the Kikwit Congolese variant of EBOV. Three primates in the control arm were given a non-functional antibody, and the 18 in the treatment arm were divided into three groups of six. All primates in the treatment arm received three doses of ZMapp, spaced 3 days apart. The first treatment group received its first dose on 3rd day after being infected; the second group on the 4th day after being infected, and the third group, on the 5th day after being infected. All three primates in the control group died; all 18 primates in the treatment arm survived.[2] Mapp then went on to show that ZMapp inhibits replication of a Guinean strain of EBOV in cell cultures.[17]

Mapp remains involved in the production of the drug through its contracts with Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of Reynolds American.[1] To produce the drug, genes coding for the chimeric mAbs were inserted into viral vectors, and tobacco plants are infected with the viral vector encoding for the antibodies, using Agrobacterium cultures.[18][19][20] Subsequently, antibodies are extracted and purified from the plants. Once the genes encoding the chimeric mAbs are in hand, the entire tobacco production cycle is believed to take a few months.[21] The development of these production methods was funded by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency as part of its bio-defense efforts following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.[22][23]

Use during the 2014 Ebola outbreak

The FDA allowed two drugs, ZMapp and an RNA interference drug called TKM-Ebola, to be used in Americans who had contracted Ebola virus disease.[24] Other countries have similar programs to allow early access through named patient programs.[25][26] 2014年10月現在[update], ZMapp had been used to treat 7 individuals infected with the Ebola virus.[27] Although some of them have recovered, the outcome is not considered to be statistically significant.[5] Mapp announced on August 11, 2014, that its supplies of ZMapp had been exhausted.[28]

Controversy

The lack of drugs and unavailability of experimental treatment in the most affected regions of the West African Ebola virus outbreak spurred some controversy.[21] The fact that the drug was first given to Americans and a European and not to Africans, according to the Los Angeles Times, "provoked outrage, feeding into African perceptions of Western insensitivity and arrogance, with a deep sense of mistrust and betrayal still lingering over the exploitation and abuses of the colonial era".[29] Salim S. Abdool Karim, the director of an AIDS research center in South Africa, placed the issue in the context of the history of exploitation and abuses. Responding to a question on how people may have reacted if ZMapp and other drugs would have been used first on Africans, said, "It would have been the front-page screaming headline: 'Africans used as guinea pigs for American drug company’s medicine'".[21]

In early August, the World Health Organization called for convening a panel of medical authorities "to consider whether experimental drugs should be more widely released." In a statement, Peter Piot (co-discoverer of the Ebola virus); Jeremy Farrar, the director of the Wellcome Trust; and David Heymann of the Chatham House Center on Global Health Security, called for the release of experimental drugs for affected African nations.[29]

At an August 6, 2014 press conference, Barack Obama, the President of the United States, was questioned regarding whether the cocktail should be fast-tracked for approval or be made available to sick patients outside of the United States. He responded, “I think we’ve got to let the science guide us. I don't think all the information's in on whether this drug is helpful."[30]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Kroll, David (2014年8月5日). “Ebola 'Secret Serum': Small Biopharma, The Army, And Big Tobacco”. Forbes

- ^ a b c d e f Qiu X, Wong G, Audet J, et al. (August 2014). “Reversion of advanced Ebola virus disease in nonhuman primates with ZMapp”. Nature 514 (7520): 47–53. doi:10.1038/nature13777. PMID 25171469.

- ^ “WHO Experts Give Nod to Using Untested Ebola Drugs” (2014年8月12日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “WHO – Ethical considerations for use of unregistered interventions for Ebola virus disease”. World Health Organization. 2014年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b “How Will We Know If The Ebola Drugs Worked?”. Forbes. 2014年9月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Ebola 'cocktail' developed at Canadian and U.S. labs”. CBC News (2014年8月5日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Keller MA, Stiehm ER (October 2000). “Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases”. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13 (4): 602–14. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.4.602-614.2000. PMC 88952. PMID 11023960.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (2014年8月29日). “Experimental Drug Would Help Fight Ebola if Supply Increases, Study Finds”. The New York Times 2014年9月1日閲覧。

- ^ Parshley, Lois (2014年8月8日). “ZMapp: The Experimental Ebola Treatment Explained”. Popular Science

- ^ Daniel, Fran (2014年8月12日). “Ebola drug provided for two Americans by Reynolds American subsidiary”. Winston-Salem Journal

- ^ 公式ウェブサイト

- ^ Olinger GG, Pettitt J, Kim D, et al. (October 2012). “Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (44): 18030–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1213709109. PMC 3497800. PMID 23071322.

- ^ “Questions and answers on experimental treatments and vaccines for Ebola”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014年8月29日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Qiu X, Audet J, Wong G, et al. (2013). “Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb”. Sci Rep 3: 3365. doi:10.1038/srep03365. PMC 3842534. PMID 24284388.

- ^ Branswell, Helen (2014年8月5日). “Experimental Ebola drug based on research discoveries from Canada's national lab”. Canadian Press

- ^ Branswell, Helen (2014年8月29日). “Scientists at Canada’s national lab created, tested Ebola drug ZMapp”. Canadian Press. Macleans

- ^ Geisbert TW (August 2014). “Medical research: Ebola therapy protects severely ill monkeys”. Nature 514 (7520): 41–3. doi:10.1038/nature13746. PMID 25171470.

- ^ “Magnifection – mass-producing drugs in record time”. National Geographic. 2014年9月11日閲覧。

- ^ Whaley KJ et al. (2014). “Emerging antibody-based products”. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 375: 107–26. doi:10.1007/82_2012_240. PMID 22772797.

- ^ Giritch A et al. (2006). “Rapid high-yield expression of full-size IgG antibodies in plants coinfected with noncompeting viral vectors”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 40 (40): 14701–14706. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606631103. PMID 16973752.

- ^ a b c Pollack, Andrew (2014年8月8日). “In Ebola outbreak, who should get experimental drug?”. The New York Times

- ^ Till, Brian (2014年9月9日). “DARPA may have a way to stop Ebola in its tracks”. New Republic

- ^ Shannon Pettypiece for Bloomberg News. 23, October 2014. Cheney in Post 9/11 Era May Be to Thank on Ebola Vaccine

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (2014年8月7日). “Second drug is allowed for treatment of Ebola”. The New York Times 2014年8月8日閲覧。

- ^ Helene S (2010). “EU Compassionate Use Programmes (CUPs): Regulatory Framework and Points to Consider before CUP Implementation”. Pharm Med 24 (4): 223–229. doi:10.1007/bf03256820.

- ^ “Spain imports US experimental Ebola drug to treat priest evacuated from Liberia with disease”. First Word Pharma (2014年8月11日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “US signs contract with ZMapp maker to accelerate development of the Ebola drug”. BMJ. BMJ. (2014年) 2014年10月9日閲覧。

- ^ Lenny M. Bernstein, Brady Dennis (2014年8月11日). “Ebola test drug’s supply ‘exhausted’ after shipments to Africa, U.S. company says”. Washington Post

- ^ a b Dixon, Robyn (2014年8月6日). “Three leading Ebola experts call for release of experimental drug”. Los Angeles Times

- ^ “Obama: 'Premature' to say U.S. should green-light new Ebola drug”. NBC News. (2014年8月6日)

External links

- Website of Mapp Biopharmaceutical

- NOVA episode "Surviving Ebola"

- “Ebola”. File on Four (BBC Radio 4). (2014年10月21日). "at 24:24, Charles Arntzen, professor of molecular biology at Arizona State University says:" It was shortly after our major 9/11 event in the US and there was money available through the US army to begin to develop preventive technology in the event of a bio terrorism attack. One of the agents that they were very interested in was the Ebola virus.""

Template:Ebola Template:Engineered antibodies Template:Monoclonals for infectious disease and toxins