製紙工場

製紙工場(せいしこうじょう、Paper_mill)とは、木材パルプや古切れなどの植物繊維から紙を抄く工場である。

エンドレスベルトを使用するフールドリニエ抄紙機をはじめとする抄紙機が発明・採用される以前は、製紙工場で抄かれる紙はすべて、専門の労働者によって1枚ずつ手作業で作られていた。

製紙の歴史

[編集]

製紙工場の起源に関する歴史的研究は、現代の著者たちによる定義の違いや用語の乱れによって複雑になっている: 現代の学者の多くは、この用語を、人力、動物力、水力など、あらゆる種類の製紙工場を無差別に指すのに使っている。現代の学者の多くは、人力であろうと動物力であろうと水力であろうと、あらゆる種類の製紙工場を無差別に指す言葉としてこの言葉を使っている。古代の製紙工場の正確な動力源を特定することなく、あらゆる製紙工場を「工場」と呼ぶ傾向があるため、特に効率的で歴史的に重要な水力工場を特定することが難しくなっている[1]。

人力および家畜動力のミル

[編集]人力や動物力による抄紙機の使用は、イスラム教徒や中国の製紙業者には知られていた。しかし、11世紀以前のイスラム教徒の製紙業において、水力による製紙工場が使用されていたことを示す証拠は、両者ともほとんどないす[2][3][4][5]。11世紀以前のイスラム教徒の製紙業において、水力による製紙工場が一般的に使用されていなかったことは、当時のイスラム教徒の著者が生産拠点を「工場」ではなく「製紙工場」と呼ぶ習慣があったことからも示唆される[6]。

学者たちは794年から795年にかけて、アッバース朝時代のバグダードに製紙工場があったことを確認している。この時代に水力が製紙に応用されていたという証拠については、学者間で議論がある[7]。モロッコの都市フェズにおいて、イブン・バットゥータは「紙のための400の石臼」について述べている[8]。イブン・バットゥータは水力の使用について言及しておらず、そのような数の水車はグロテスクなほど多いため、この箇所は一般的に人力または動物力を指していると考えられている[4][8]。

水力製紙

[編集]

アル=アンダルスにおける製紙工場に関する徹底的な調査でも、水力で動く製紙工場は発見されなかったし、キリスト教によるレコンキスタ後のスペインの財産分配に関する書物(Repartimientos)にも、製紙工場に関する記述はない[9]。アラビア語の書物には、製紙工場という用語が製紙に関連して使用されたことはなく、当時のイスラム教徒の製紙に関する最も詳細な記述であるジリッド朝のスルタン、ビールーニーの書物には、純粋に手工芸という観点から製紙技術が記述されている[9]。ドナルド・ヒルは、11世紀のペルシア人学者アブ・レイハン・ビルニの著作の中に、サマルカンドにおける水力製紙工場についての言及の可能性を特定したが、その一節が水力製紙工場について言及していると「確信を持って言うには短すぎる」と結論づけている[10][11]。レオール・ハレヴィ(Leor Halevi )はこれをサマルカンドが初めて紙の生産に水力を利用した証拠と見ているが、当時のイスラム世界の他の場所で水力が紙漉きに適用されていたかどうかは不明であると指摘している[12]。 ロバート・I・バーンズは、この言及が孤立していることや、13世紀以前のイスラムの紙漉きにおいて手作業が普及していたことを考慮し、懐疑的な立場を崩していない[1]。

ヒルは、製紙工場は 1150 年代の初期キリスト教カタロニア語の文書に登場し、イスラム起源を暗示している可能性があるが、確固たる証拠が不足していると指摘している[13][14]。しかしバーンズは、証拠を再検討した後、初期のカタロニアの水力製紙工場の訴訟を却下した[15]。

イタリアのファブリアーノに残る中世の文書に、初期の油圧式スタンピング工場が確認されていることも、まったく事実無根である[16]。

水力製紙工場の明確な証拠は、スペイン領アラゴン王国の1282年にまで遡る[17]。キリスト教徒である国王ペドロ3世による勅令は、製紙の中心地であるシャティバに王立の「モレンディヌム」、すなわち適切な水力製紙工場を設立することを定めている[17]。この初期の水力製紙工場は、シャティバのムーア人居住区でイスラム教徒によって運営されていたが[18]、地元のイスラム教徒の製紙コミュニティの一部からは反感を買っていたようである。この文書では、パルプを手作業で叩く伝統的な製紙方法を継続する権利を保証し、新しい工場での労働を免除する権利を認めている[17]。

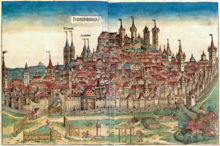

アルプス以北で最初の恒久的な製紙工場は、1390年にウルマン・シュトローマーによってニュルンベルクに設立され、後に豪華な絵入りの『ニュルンベルク年代記』に描かれている[19]。14世紀半ば以降、ヨーロッパの製紙工場では、多くの作業工程が急速に改善された[20]。

産業機械が使われる以前の製紙工場の規模は、桶の数を数えることで表現されていた。したがって、「1桶」の製紙工場には、1人の桶師、1人のクッチャー、その他の労働者しかいなかった[21]。

15世紀

[編集]イングランドで最初の製紙工場に関する記述は、1495年頃にウィンケン・デ・ワードが印刷した本の中にあり、その工場はハートフォード近郊のジョン・テイトのものであった[22]。

19世紀

[編集]このプロセスを機械化する機械の初期の試みは、1799年にフランス人のニコラス・ルイ・ロベールによって特許を取得されたが、成功とはみなされなかった。しかし1801年、ジョン・ギャンブルによって図面がイギリスに持ち込まれ、ヘンリー・フールドリニエとシーリー・フールドリニエの兄弟に渡った。彼らの最初の成功した機械は、1803年にハートフォードシャーのフロッグモアFrogmoreに設置された[22][23]。1809年には、フロッグモア ミル(Frogmore Paper Mill)のすぐ隣のApsley Millで、John Dickinsonが別の種類の抄紙機の特許を取得し、設置した。この抄紙機では、無限に回転する平らなワイヤーに希薄なパルプ懸濁液を流し込むのではなく、ワイヤーで覆われた円筒を型として使用した。円筒形の型をパルプ懸濁液の入った桶の中に部分的に沈め、型が回転するにつれて水をワイヤーを通して吸い上げ、円筒上に繊維の薄い層を残す。これらのシリンダー型機械は、その名の通り、フールドリニエ機械メーカーにとって強力な競争相手であった。北米の製紙業界で最初に使用されたのは、このタイプの機械であった。 1850年までに英国の製紙生産量は10万トンに達したと推定されている。その後の開発により、マシンのサイズと能力が向上し、また紙を確実に生産できる大量の代替パルプ源が求められるようになった。初期の工場の多くは小規模で、農村部に立地していた。そのため、原料の供給元により近い都市部やその近郊に、より大規模な工場が建設されるようになった。これらの工場は、原料が船で運ばれる港や製紙市場の近くに立地することが多かった。世紀末までには、英国の製紙工場は300を下回り、35,000人を雇用し、年間650,000トンの紙を生産していた[24]。

20世紀

[編集]

20世紀初頭には、紙の需要の高さから、ニューイングランドをはじめ世界各地に製紙工場が誕生した。インフラと工場都市を持つアメリカは、世界最大の生産国だった[25]。その中でも製紙生産において最も重要だったのはマサチューセッツ州ホルヨーク[26]で、1885年までに世界最大の製紙会社となり、その10年間に5大陸の工場を設計し、アメリカ最大の製紙工場を監督した技術者D.H.&A.B.タワー兄弟の本拠地となった[27][28]。しかし、20世紀が進むにつれて、このディアスポラは、より多くのパルプ供給と労働力を手に入れることができるアメリカの北と西へと移動していった。この頃、紙生産の世界的なリーダーが数多く存在し、そのひとつがウィリアム・ウェントワース・ブラウンが経営するニューハンプシャー州ベルリンのブラウン社であった。1907年、ブラウン社は、カナダのケベック州ラ・トゥークからフロリダ州ウェストパームまで広がる敷地で[29]、3,000万から4,000万エーカーの森林を伐採した[30]。

1920年代、ナンシー・ベイカー・トンプキンスは、ハマミル・ペーパー・カンパニー、ホノルル・ペーパー・カンパニー、アップルトン・コーテッド・ペーパー・カンパニーといった大手製紙会社の代理人として、紙製品の流通業者への販売促進を行っていた。この種のビジネスは世界で唯一と言われ、1931年にトンプキンスが始めた。不況にもかかわらず繁栄した[31]。

丸太を製紙工場に送るために、地元の川で「丸太運び」が行われた。20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて、製紙工場は閉鎖され始め、丸太運びは瀕死の技術となった[32]。新しい機械が導入されたため、多くの工場労働者が解雇され、歴史ある製紙工場の多くが閉鎖された[33]。

特徴

[編集]製紙工場には、完全統合工場と非統合工場がある。一貫工場は、パルプ工場と製紙工場が同じ敷地内にある。このような工場は、丸太や木材チップを受け入れ、紙を生産する。

現代の製紙工場は、効率的で複雑な一連の工程と制御技術によって、大量のエネルギー、水、木材パルプを使用し、多様な用途に使用できる1枚の紙を生産している。 現代の抄紙機は、長さ150メートル(500フィート)、幅10メートル(400インチ)の紙を生産し、時速97キロメートル(60マイル)以上で稼働することができる[34]。抄紙機の主なサプライヤーは、メッツォとフォイトの 2 社である。

参考文献

[編集]- Burns, Robert I. (1996), “Paper comes to the West, 800−1400”, in Lindgren, Uta, Europäische Technik im Mittelalter. 800 bis 1400. Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 413–422, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Hunter, Dard (1930), Papermaking through Eighteen Centuries, New York

- Hunter, Dard (1943), Papermaking the History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, New York

- Lucas, Adam Robert (2005), “Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe”, Technology and Culture 46 (1): 1–30, doi:10.1353/tech.2005.0026

- Thompson, Susan (1978), “Paper Manufacturing and Early Books”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 314 (1): 167–176, Bibcode: 1978NYASA.314..167T, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb47791.x

- Tschudin, Peter F. (1996), “Werkzeug und Handwerkstechnik in der mittelalterlichen Papierherstellung”, in Lindgren, Uta, Europäische Technik im Mittelalter. 800 bis 1400. Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 423–428, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Stromer, Wolfgang von (1960), “Das Handelshaus der Stromer von Nürnberg und die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Papiermühle”, Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 47: 81–104

- Stromer, Wolfgang von (1993), “Große Innovationen der Papierfabrikation in Spätmittelalter und Frühneuzeit”, Technikgeschichte 60 (1): 1–6

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin : "Science and Civilization in China", Chemistry and Chemical Technology (Vol. 5), Paper and Printing (Part 1), ケンブリッジ大学出版局, 1985

脚注

[編集]- ^ a b Burns 1996, pp. 414−417

- ^ Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin 1985, pp. 68−73

- ^ Lucas 2005, p. 28, fn. 70

- ^ a b Burns 1996, pp. 414f.: It has also become universal to talk of paper "mills" (even of 400 such mills at Fez!), relating these to the hydraulic wonders of Islamic society in the east and west. All our evidence points to non-hydraulic hand production, however, at springs away from rivers which it could pollute.

- ^ Thompson 1978, p. 169: European papermaking differed from its precursors in the mechanization of the process and in the application of water power. Jean Gimpel, in The Medieval Machine (the English translation of La Revolution Industrielle du Moyen Age), points out that the Chinese and Arabs used only human and animal force. Gimpel goes on to say: "This is convincing evidence of how technologically minded the Europeans of that era were. Paper had traveled nearly halfway around the world, but no culture or civilization on its route had tried to mechanize its manufacture."'

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 414f.: Indeed, Muslim authors in general call any "paper manufactory" a wiraqah - not a "mill" (tahun)

- ^ Burns 1996, p. 414:Al-Hassan and Hill also use as evidence the statement by Robert Forbes in his multivolume Studies in Ancient Technology that "in the tenth century [AD] floating mills were found on the Tigris near Baghdad." Though such captive mills were known to the Romans and were used in 12th-century France, Forbes offers no citation or evidence for this unlikely application to very early papermaking. The most erudite authority on the topography of medieval Baghdad, George Makdisi, writes me that he has no recollection of such floating papermills or any papermills, which "I think I would have remembered."

- ^ a b Tschudin 1996, p. 423

- ^ a b Burns 1996, pp. 414f.

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), A history of engineering in classical and medieval times, Routledge, pp. 169–71, ISBN 0-415-15291-7

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 414: Donald Hill has found a reference in al-Biruni in the 11th century to stones "fixed to axles across running water, as in Samarkand with the pounding of flax for paper," a possible exception to the rule. Hill finds the notice "too brief to enable us to say with certainty" that this was a water-powered triphammer.

- ^ Leor Halevi (2008), “Christian Impurity versus Economic Necessity: A Fifteenth-Century Fatwa on European Paper”, Speculum (Cambridge University Press) 83 (4): 917–945 [917–8], doi:10.1017/S0038713400017073

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), A history of engineering in classical and medieval times, Routledge, p. 171, ISBN 0-415-15291-7

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 414f.: Thomas Glick warily concludes that "it is assumed but not proved" that Islamic Xàtiva had hydraulic papermills, noting that the pertinent Arabic description was "a press." Since the "oldest" Catalan paper is physically the same as Islamic Xàtiva's, he notes, their techniques "can be presumed to have been identical" - reasonable enough for Catalan paper before 1280. My recent conversations with Glick indicate that he now inclines to non-hydraulic Andalusi papermaking.

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 415: Currently Oriol Valls i Subin't, director of the History of Paper department of the Museos Municipales de Historia in the Instituto Municipal de Historia at Barcelona, has popularized a version of that thesis, in which Christian paper mills multiplied marvelously along the Catalan rivers "from Tarragona to the Pyrenees" from 1113 to 1244. His many articles and two books, valuable for such topics as fiber analysis in medieval paper, continue to spread this untenable and indeed bizarre thesis. As Josep Madurell i Marimon shows in detail, these were all in fact cloth fulling mills; textiles were then the basic mechanized industry of the Christian west.

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 416: Fabriano's claim rests on two charters - a gift of August 1276, and a sale of November 1278, to the new Benedictine congregation of Silvestrine monks at Montefano. In each, a woman recluse-hermit gives to the monastery her enclosure or "prison" - Latin carcer; misread by Fabriano partisans as a form of Italian cartiera or paper mill! There is no papermaking in these documents, much less hydraulic mills.

- ^ a b c Burns 1996, pp. 417f.

- ^ Thomas F. Glick (2014). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 385. ISBN 9781135459321

- ^ Stromer 1960

- ^ Stromer 1993, p. 1

- ^ Dard Hunter (1943), Papermaking, the History and Technology of an Ancient Craft, Knopf

- ^ a b “History of Papermaking in the United Kingdom”. www.baph.org.uk. 6 September 2020閲覧。

- ^ “About the Archives”. Apsley Paper Trail. 3 March 2024閲覧。

- ^ “The cylinder mould machine”. www.thepapertrail.org.uk. 6 September 2020閲覧。

- ^ “The World's Paper Trade”. The Paper Makers' Monthly Journal (London: Marchant Singer & Co.) XLVII (3): 84. (March 15, 1909). "The United States, the largest producing country, ranks fourth in the value of the exports of paper"

- ^ 『洋紙業を築いた人々 (紙業叢書 ; 第2編)』製紙記念館、1952年、24頁。「王子製紙の初代専務となる大川平三郎は、1879(明治12)年に選ばれてアメリカに渡り、ホルヨークのホルブルック製紙工場に入って8ヶ月間職工同様に実地研究して技術を持ち帰った」

- ^ “Eight Paper Towns”. The Inland Printer (Chicago) II (10). (July 1885).

- ^ “Emory Alexander Ellsworth”. Journal of the Boston Society of Civil Engineers III (8): 480. (October 1916). "In 1879 Mr. Ellsworth left the firm of Davis & Ellsworth to become principal assistant and head draftsman for D. H. & A. B. Tower, of Holyoke, who were the largest firm of paper mill architects in the country at that time, and who designed no less than twenty paper mills in the city of Holyoke alone"

- ^ Defebaugh, James Elliott (1907). History of the lumber industry of America April 5, 2012閲覧。

- ^ Defebaugh, James Elliott (1907). History of the lumber industry of America April 5, 2012閲覧。

- ^ “Monday, July 9, 1934”. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. (1934) 21 August 2017閲覧。.

- ^ “Paper Mill Closures of America”. April 5, 2012閲覧。

- ^ “Urban Decay” (16 October 2010). April 5, 2012閲覧。

- ^ “Metso supplied SC paper machine line sets a new world speed record at Stora Enso Kvarnsveden”. 2008年12月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年4月12日閲覧。

関連項目

[編集]- 紙

- 洋紙

- 和紙

- 紙の作り方

- 蔡倫

- 製紙業

- 抄紙機

- 切り代問題

- 製紙工場一覧

- 製紙による環境汚染

- ロバート C. ウィリアムズ製紙博物館

- ダード・ハンター

- パピール・ファブリック - 1876年(明治9年)操業の京都府営の洋紙製紙工場。