エルコシュ

エルコシュ シリア語:ܐܲܠܩܘܿܫ アラビア語:ألقوش[1] | |

|---|---|

|

村 | |

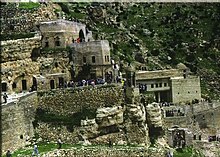

エルコシュの風景 | |

| 座標:北緯36度43分55.6秒 東経43度5分42.6秒 / 北緯36.732111度 東経43.095167度座標: 北緯36度43分55.6秒 東経43度5分42.6秒 / 北緯36.732111度 東経43.095167度 | |

| 国 |

|

| 行政区域 | ニーナワー県 |

| 地区 | テル・カイーフ |

| 起源 | 紀元前1500頃 |

| 等時帯 | GMT +3 |

| • 夏時間 | GMT +4 |

エルコシュ (英語: Alqosh, Alkosh, Alqush, シリア語 (マクロランゲージ): ܐܲܠܩܘܿܫ,[2][3][4] ユダヤーアラム語: אלקוש, アラビア語: ألقوش,[5]は、イラク北部のニネヴェ平原にある集落であり、 テル・カイーフ行政区域に属する村である。ニーナワー県の県都であるモースル市から約45㎞北部に位置する。

住民の多数派はアッシリア人とヤズィーディー教徒であり、少数派にアラブ人がいる。

カルデア教会に所属する住民は、一般に、民族的にはアッシリア人に分類される[6][7][8]。しかし彼らは、しばしばメンバーがアッシリア人と呼ばれるアッシリア東方教会には所属しておらず、カルデア人という言葉と対照的である[9][10][11]。

こうして、サミ・ズバイダはエルコシュを「もう一つのアッシリア人の中心地」と呼んだ。

また、1933年にエルコシュより北の地域で起こったアッシリア人に対するシメーレの虐殺の際には、当時の大英帝国のモスールの管理監査官であったR. S. スタンフォード大佐は、虐殺があった際、他の虐殺も計画されていた、と述べている[12]。ロナルド・センピル・スタンフォードは、エルコシュについて「数百人のアッシリア人の男性、女性、子供が自分たちの村での略奪から逃れてきており、カルデア人のクリスチャンの慈善によって生活している」と述べている[13]。

キリスト教[編集]

東方教会において、エルコシュはラバン・ホーミズド修道院に近い事から重要視されるようになった。修道院の名は、17世紀の創始者であるラバン・ホーミズドにちなみ(ラバンは「僧侶」を意味する)、彼は東方教会の教会の聖人として敬われている。

この修道院は山の斜面に建てられ、シリア正教会以外の他の東方教会の中心地から遠くない東方教会の学習の中心地であった。また15世紀後半以降は東方教会の長老たちの墓所であり、シムンⅥ世(1503-1538)の時からエリヤの系統と呼ばれた長老たちの時代まで、彼らの司教座であった。冬季には雪いよりエルコシュと切り離されて孤立するため、長老たちの永住地にはならなかった[14]。その長老たちの系統は、通常はモースル系統と呼ばれるか、またはエルコシュの住人と呼ばれた。[15]。

1552年の分裂の際に、修道院の大修道院長であるヨハナム・スラーガが、長老の世襲制に不満を持っていた司教たちによって、正当でない形で長老に選ばれた。伝統に従えば、長老は特定の家族の一員だけが昇進できる地位、つまり大司教(首都大司教)だけが任命することができる。そのため、スラーガはローマに旅行し、そこで新しく選ばれた長老として謁見し、カトリック教会と合同し、教皇に任命されて長老と承認された。彼とその後継者(最終的に正式にローマとの合同を破棄した)は、居住地を更に東に定めた。この分裂は、歴史家が東方教会の伝統主義者と呼ぶのとは反対に、カルデア・カトリック教会の興隆に繋がり、1976年には正式にアッシリア東方教会の名称を採用した[16][17]。

17から18世紀には、スラーガが1552年に破壊した「正統派」のエルコシュの長老の系統がローマに接近した。特に58年に渡るエリヤⅪ/Ⅻデンカ(1722-1778)の治世の間はそうであった。彼はローマに度々手紙を送り、その一部はカトリックの教えに沿った信仰告白が含まれていたが、ローマ教皇の承認は得られなかった[18][19]。しかし、「正統派」の伝統主義者から長老が選ばれるのは、特定の家族の一員だけであり、自分を1778年以降カトリックであると考えていたヨハナム・ホーミズド(1760-1838)が、1830年にカルデア・カトリック教会の長老に選ばれた[20][19]。

預言者ナホムとの関連[編集]

1847年にこの地域を訪れたオースティン・ヘンリー・ラヤードは、「非常に古代にさかのぼる伝統に基づき、この村には、旧約聖書において、「ニネベについての宣告。エルコシュ人ナホムの幻の記録。」という書き出しから始まる預言者ナホムの墓が存在する」と報告した[21]。ヒエロニムスがナホムの出生地をガリラヤだと同定した一方で、ラヤードは碑文や古代の遺物が少ないながらも、エルコシュの伝統を軽く見るべきではない、と考えた[22]。イラクのユダヤ人は、シャブオットの間に遺跡に巡礼を行い「ナホムの墓に巡礼した事のない者は、本当の喜びを知らない。」と述べた[23]。1948年に、ユダヤ人がイラクから追放されるか、あるいはイスラエルに移住した際、ユダヤ人の管理者は建築物の管理を現地のカルデア・カトリック教徒に委託した[24]。2017年に行なわれたある調査によって、構造物に崩壊の危険性があると判定され、その後安定化の作業が始まった[25][26]。

襲撃事件[編集]

- 1401 - チムールにより攻撃され、略奪された[19]。

- 1508 - バグダードの高官(パシャ)であったバル・ヤク(ムラード・ベイ)により攻撃された[19]。

- 1828 - アマディーヤの支配者であったモサ・パシャが村に接近し、ラバン・ホーミズド修道院に火を放った[27]。

- 1831 - ソラン首長がエルコシュを襲撃し、300人近くの村人を殺害した[28]

- 1832 - ラワンドゥズのムハンマド・パシャがエルコシュを襲撃し、住民のうち600人以上を殺害した[27]。

- 1840 - ミラ・クーアの兄弟であるリソウル・ベックが襲撃を繰り返した[27]。

- 1843 - ラバン・ホーミズド修道院がクルド人によって襲撃された。その際、千冊の写本が破壊された可能性がある[28]。

- 2014 - ISILがエルコシュに接近し、ほぼ全ての住民が避難した。しかし、多くの男性及び若者は村を守るためにエルコシュに残った。ISILはペシュメルガ及びドゥェク・ナウシャの介入後、村の占領に失敗した。[29]。

人口[編集]

2020年3月に、シュラマ財団が村の人口を4,567人と報告した:1,015世帯はカルデア・カトリック教派であった[30]。

代表なき国家民族機構によると、住民のほとんどはアッシリア人であり、少数派としてヤズィーディー教徒がいる[31]。1913年の時点では、Joseph・Tfinkdjiによると、7千人のカルデア・カトリックが居住していた[32]。多くの住民は1970年代以降移住しており、少なくとも4万人のエルコシュ出身(Alqushnaye)の移民、及びその2世、3世がデトロイト、ミシガンの都市、シドニー西部の郊外にあるフェアーフィールド、カリフォルニア州のサンディエゴに居住している。

2010年2月にイラク北部のアッシリア人、カルデア人、シリア語系の住民が攻撃を受け、モースルからニネヴェ平原へと避難を余儀なくされた。ある国連の報告書によると、504人のアッシリア人が一度にエルコシュに移住した。2003年のイラク戦争以降、モースルやバクダードから多くのアッシリア人が安全のためにエルコシュに避難している。2020年の集落の人口は、大まかに4,600人と推定されている。[33]。

クルディスタン地域政府(KRG)との関係[編集]

2014年、エルコシュの市長フェイズ・ジャーワレーが不当に拘留され、クルディスタン民主党のララ・ザラに交代させられたが、最終的に住民の抗議により復職した[34]。ジャーワレーは再び、2017年にイラク連邦法廷に却下された虚偽の汚職の告発によって、KRGによって拘留され、交代させられた[35][36]。

気候[編集]

エルコシュはステップ気候(BSh)であり、極端に暑く乾燥した夏と、涼しく湿潤な冬を伴う。

| エルコシュの気候 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 月 | 1月 | 2月 | 3月 | 4月 | 5月 | 6月 | 7月 | 8月 | 9月 | 10月 | 11月 | 12月 | 年 |

| 平均最高気温 °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

20 (68) |

26 (79) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

43 (109) |

40 (104) |

38 (100) |

30 (86) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

27.4 (81.3) |

| 平均最低気温 °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

12.9 (55.3) |

| 降水量 mm (inch) | 39 (1.54) |

69 (2.72) |

51 (2.01) |

27 (1.06) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (0.24) |

36 (1.42) |

60 (2.36) |

288 (11.35) |

| 平均降水日数 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 65 |

| 出典:World Weather Online (2000-2012)[37] | |||||||||||||

エルコシュ出身の著名人[編集]

- ヨハナン・ホーミズド (1760–1838)、 カルデア・カトリック教会の長老 1830–1838

- ジョセフ・Ⅵ・アウド (1790–1878)、 カルデア・カトリック教会の長老 1847–1878

- トマ・アウド (1854–1918)、 オルーミーイェの大司教

- ヨーセフ・Ⅵ・エマヌエル (1852–1947)、 カルデア・カトリック教会の長老 1900–1947

- パウロ・Ⅱ・チェイクホ (1906–1989)、 カルデア・カトリック教会の長老 1958–1989

- ヒルミス・アボーナ (1940–2009)、 歴史家

- エミル・シモウン・ノナ (1967– )、 モースルの大司教 2009–2015、シドニーの使徒聖トーマスのカルデア・カトリック管区の司教 2015–

脚注[編集]

- ^ معاناة الكورد الايزديين فيá ظل الحكومات العراقية، 1921-2003. University of California, Berkeley, USA. (2008)

- ^ Maclean, Arthur John (1901). Dictionary of the Dialects of Vernacular Syriac. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 13b

- ^ Payne Smith, Robert (1879–1901) (ラテン語). Thesaurus Syriacus. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 221

- ^ Thomas A. Carlson, “Alqosh — ܐܠܩܘܫ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified June 7, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/19.

- ^ Frazee, Charles A. (2006). Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007

- ^ Hirmis, Aboona (2008). Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: Intercommunal relations on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire. United States: Cambria Press. pp. 36

- ^ The Fate of Iraq's Indigenous Communities Fair Observer 2017年1月25日

- ^ James F. Coakley, "Assyrians" in Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron M. Butts, George A. Kiraz and Lucas Van Rompay quote: Among Chaldean Catholics, ‘Assyrian’ has had to compete with ‘Chaldean’ as the preferred ethnic name. Some have adopted ‘Assyro-Chaldean’ as a compromise

- ^ Yasmeen Hanoosh. The Chaldeans: Politics and Identity in Iraq and the American Diaspora. Bloomsbury Publishing; 30 May 2019. ISBN 978-1-78673-600-0. p. 92|quote=the 1920s–70s was an era during which the Assyrians witnessed gradual political and social marginalization in Iraq while the Chaldeans looked collectively ahead towards progress

- ^ Nadia Jones-Gailani. Transnational Identity and Memory Making in the Lives of Iraqi Women. University of Toronto Press; 20 August 2020. ISBN 978-1-4875-0316-1. p. 50|quote=The origin of each present-day group (Chaldean, Assyrian and Syriac) is still a topic of contention amongst scholars.

- ^ Liora Lukitz. Iraq: The Search for National Identity. Routledge; 5 July 2005. ISBN 978-1-135-77821-7. p. 27.|quote=the Assyrians had the support of Chaldeans, Jacobites, Protestants, Catholic Syrians, Armenians and even Yazidis and Jews

- ^ Zubaida, Sami (2000). “Contested Nations: Iraq and the Assyrians”. Nations and Nationalism 6 (3): 363–382. doi:10.1111/j.1354-5078.2000.00363.x. ISSN 1354-5078.

- ^ The Tragedy of the Assyrians. G. Allen & Unwin, Limited; 1935. p. 187]

- ^ David Wilmshurst (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. Peeters Publishers. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-90-429-0876-5

- ^ F. Kristian Girling, "The Chaldean Catholic Church: A study in modern history, ecclesiology and church-state relations (2003–2013)" (Department of Theology, Heythrop College, University of London), p.43

- ^ Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2

- ^ Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0

- ^ Heleen L. Murre-Van Den Berg, "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" in Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies Volume 2 (1999 [2010), p. 247,

- ^ a b c d David Wilmshurst (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913 (582nd ed.). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9042908769

- ^ Frazee, Charles A. (2006). Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923. Cambridge University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-521-02700-7

- ^ ナホム書 1章1節 聖書 新改訳2017 ©2017 新日本聖書刊行会

- ^ Austen Henry Layard (1849). Nineveh and Its Remains. J. Murray. p. 233

- ^ Neurink, Judit (2015年7月5日). “Kurdistan needs help to preserve its Jewish heritage”. The Jerusalem Post 2015年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ Hedow, Amer (2009年8月3日). “An AlQosh Man Struggles to Keep a Promise to an Old Friend”. chaldean.org 2020年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Progress made on saving Prophet Nahum's tomb in Iraq”. The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com 2018年4月23日閲覧。

- ^ Neurink, Judit (2018年3月21日). “Hebrew prophet's tomb in Iraq saved from collapse” (英語). Al-Monitor 2018年4月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Geoff Hann; Karen Dabrowska; Tina Townsend-Greaves (2015). Iraq: The ancient sites and Iraqi Kurdistan. ISBN 978-1841624884

- ^ a b Wilmhurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organization of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. pp. 205

- ^ Costa-Roberts, Daniel (2015年3月15日). “8 things you didn't know about Assyrian Christians”. PBS 2015年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ Shlama Foundation

- ^ “UNPO: Assyria: Crowds Gather to Protest Mayor's Unfounded Expulsion”. unpo.org. 2020年5月24日閲覧。

- ^ Joseph Tfinkdji, "L'Église Chaldéenne Catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui", in Annuaire Pontifical Catholique 17 (1914). pp. 449-525.

- ^ “Population Project” (英語). Shlama Foundation. 2020年5月24日閲覧。

- ^ “Iraqi Christians reject second mayor installed by pro-Kurd council” (英語). World Watch Monitor. 2020年5月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Post - Assyrian Policy Institute” (英語). assyrianpolicy. 2019年7月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Iraqi Christians reject second mayor installed by pro-Kurd council” (英語). World Watch Monitor. 2019年7月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Alqosh, Ninawa Monthly Climate Average, Iraq”. World Weather Online. 2017年1月22日閲覧。

参考文献[編集]

- Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2006). ISBN 9780521027007

- Addai Scher, Notice sur les manuscrits syriaques conservés dans la bibliothèque du couvent des Chaldéens de Notre-Dame-des-Semences, Journal Asiatique Sér. 10: 8, 9 (1906). This may be found online at Gallica by searching for "Journal Asiatique". An English translation of the first portion is at tertullian.org

- 1552年の分裂から1830年まで東方教会の長老の一覧

外部リンク[編集]

![]() ウィキメディア・コモンズには、エルコシュに関するカテゴリがあります。

ウィキメディア・コモンズには、エルコシュに関するカテゴリがあります。