「ニバレノール」の版間の差分

en:Nivalenol 2021年6月15日 (火) 18:46 を一部翻訳。 |

(相違点なし)

|

2021年8月20日 (金) 00:08時点における版

この項目「ニバレノール」は途中まで翻訳されたものです。(原文:https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nivalenol&oldid=1028740483) 翻訳作業に協力して下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴、翻訳のガイドラインも参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2021年8月) |

| Nivalenol (NIV) | |

|---|---|

| |

別称 (3α,4β,7α)-12,13-epoxy-3,4,7,15-tetrahydroxy-trichothec-9-en-8-one[1] | |

| 識別情報 | |

| CAS登録番号 | 23282-20-4 |

| PubChem | 31829 |

| ChemSpider | 29515 |

| UNII | 5WOP02RM1U |

| KEGG | C06080 |

| ChEBI | |

| |

| |

| 特性 | |

| 化学式 | C15H20O7 |

| モル質量 | 312.32 g mol−1 |

| 外観 | solid |

| 密度 | 1.6±0.1 g/cm³ |

| 融点 |

222–223 °C |

| 沸点 |

585.1±50 °C |

| 水への溶解度 | 3.54*10^5 mg/L at 25 °C |

| 溶解度 | soluble in polar organic solvents |

| 酸解離定数 pKa | 11.78 |

| 危険性 | |

| GHSピクトグラム |    [2][3] [2][3]

|

| GHSシグナルワード | Danger [2] |

| Hフレーズ | H225, H300, H302, H312, H332, H310, H319, H330 [2][3] |

| Pフレーズ | P210, P241, P260, P262, P264, P270, P271, P280, P284, P301+310, P302+350, P304+340, P310, P320[2][3] |

| NFPA 704 | |

| 引火点 | 5 °C (41 °F; 278 K) [3] |

| 発火点 | 525 °C (977 °F; 798 K) [3] |

| 許容曝露限界 | 40 ppm (70 mg/m3) [3] |

| 半数致死量 LD50 | 19.5 mg/kg (rats, oral), 38.9 mg/kg (mouse, oral) |

| 特記なき場合、データは常温 (25 °C)・常圧 (100 kPa) におけるものである。 | |

ニバレノール(Nivalenol,NIV)はトリコテセン類のマイコトキシンである。自然界では主にFusarium 種の真菌に含まれている。Fusarium 種は、北半球の温帯地域で最も一般的なマイコトキシン生産菌に属しており、その為、食用作物生産産業にとって大きなリスクとなっている[4]。

この真菌は、様々な農産物(穀物)やその加工品(麦芽、ビール、パン)に多く含まれている。Fusarium 種は農作物に侵入して成長し、湿った涼しい環境下でニバレノールを生成する可能性がある[4]。

ニバレノールの影響を受けた後に観察される症状は、飼料拒否、嘔吐、胃腸や皮膚の炎症や壊死、免疫機能障害[5]であり、また、白血球数低下をもたらす血液毒である[5]。

歴史

1946年から1963年にかけて、日本、韓国、インドでFusarium に感染した穀物を摂取したことによる中毒症状(赤カビ病、Scrabby grain disease)が数例報告された。致死的な症例は報告されておらず、吐き気、嘔吐、下痢、腹痛などの軽い症状のみであった。これらの事例ではF.graminaerumが分離され、ニバレノールまたはデオキシニバレノールの混入が示唆された。

同時期に、インドと中国で100人以上の患者を伴う2つのアウトブレイクが報告された。これらのアウトブレイクでも死に至った症例は報告されなかった。

1987年にインドで発生した急性のアウトブレイクでは、約50,000,000人が罹患した事が記録されている。パン製造に使用された雨晒しの小麦から、ニバレノール(24サンプル中2サンプルで0.03〜0.1mg/kg)、デオキシニバレノール(24サンプル中11サンプルで0.34〜8.4mg/kg)、アセチルデオキシニバレノール(24サンプル中4サンプルで0.6〜2.4mg/kg)などの複数のFusarium 毒素が検出された。致死的な症例は今回もなく、報告された症状は腹痛、下痢、血便、嘔吐であった。これらの事例は、ニバレノールの主な危険性はフザリウムに感染した穀物に由来し、主に管理されていない小麦やその他の穀物の流通ルートを経由して、更に加工されたり、別のルートで食物連鎖に入ったりすることを示している[6]。

ニバレノール中毒の武器化とその他の事例

Nivalenol as well as deoxynivalenol and T-2 toxin have been used as biological warfare agents in Laos and Cambodia as well as in Afghanistan. The Soviet Union has been alleged to have provided the mycotoxins and to have used them themselves in Afghanistan. All three compounds could be identified in the vegetation at affected sites, whereas T-2 toxin could also be found in urine and blood samples of victims.[7]

The best documented use of trichothecenes in warfare is the yellow rain controversy, this describes a number of attacks in Southeastern Asia as well as Laos and Afghanistan, which used a “yellow rain” as described by witnesses. The toxins were delivered as what has been described as a cloud of yellow dust or droplets. An article by L. R. Ember published in 1984 in Chemical Engineering News describes the use of trichothecene mycotoxins as biological weapons in Southeast Asia in a very detailed manner.[8] In it reports of survivors and eyewitnesses as well as prisoners of war and soviet informants can be found together with information on the presence of soviet technicians and laboratories. This led to the conclusion that these toxins have been used in Southeast Asia and Afghanistan. The Russian government however refuses to give a statement on these pieces of evidence. Furthermore, it has been shown that samples taken on the location of attacks contain these toxins, while sites that have not been attacked do not show any signs of toxins in them.

Even though it remains questionable if all witness reports are reliable sources of evidence, the symptoms recorded are typical for intoxication with trichothecenes.

There was a number of ways in which trichothecenes were weaponized, such as dispersion as aerosol, smoke, droplets or dust from aircraft, missiles, handheld devices or artillery.[9]

食品業界における安全性ガイドライン

In 2000 a scientific opinion on nivalenol was issued by the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF). A temporary tolerable daily intake (t-TDI) of 0–0.7 µg/kg bw per day was issued after evaluation of the general toxicity as well as the haematoxicity and the immunotoxicity. This t-TDI was reaffirmed by the SCF in 2002.

In 2010 the Japanese Food Safety Commission (FSCJ) issued a t-TDI of 0.4 μg/kg bw per day.

Between 2001 and 2011 the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) collected data from 15774 nivalenol occurrences in 18 European countries to be assessed. This led to the establishment of a TDI of 1.2 µg/kg bw per day. Nivalenol was in this studies not found to be genotoxic, but well haematotoxic and immunotoxic.[4]

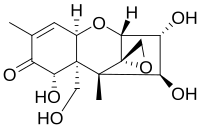

構造と反応性

マイコトキシンファミリーの一員であるニバレノールは、この毒素ファミリーのすべてのメンバーが持つ共通の構造を持っている。この構造は、シクロヘキセンとテトラヒドロピランがC6とC11で縮合した基本構造を含んでいる。さらに、テトラヒドロピランのC2とC5はエチレン基で結ばれており、シクロヘキセンのC8にはケト基が結合している。テトラヒドロピランのC12とC13には、殆どのメンバーで反応性を担うエポキシド基が結合している。C3,C4,C7,C15の残りの基だけが,それぞれのマイコトキシンで異なる。ニバレノールの場合、残りの4つの基はそれぞれ置換されたヒドロキシル基であり、それらの極性特性の為、親水性化合物やサブグループの存在下での反応性を高めている。酸性媒体中では、ケト基はプロトンと反応して、極性と反応性を促進することができる。しかし、全体としては、エポキシド基が分子の反応性にとって最も重要である[10]。

生合成

The synthesis of nivalenol is a 16 step process. It can differ in step 11 to step 14 depending on the order in which the reaction controlling trichodiene synthases TRI1, TRI13 and TRI7 are catalyzing. Famesyl pyrophosphate is used as starting compound for the synthesis of nivalenol. Its cyclization reaction to trichodiene is catalyzed by terpene cyclase trichodiene synthase (Tri5). This reaction is followed by several oxidation reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (encoded by TRI4). Thereby hydroxyl groups were substituted to the carbon atoms C2, C3 and C11 and one oxygen was added to C12 and C13 facilitating the formation of an epoxide group. This results in the intermediate isotrichotriol.

In a further reaction trichotriol was gained through a shift of the C11 hydroxyl group of the isotrichotriol to the C9, similar the double bond shifted from C9=C10 to C10=C11. Trichotriol reacts in a non-enzymatic cyclization reaction to its isomere isotrichodermol. In the reaction the hydroxyl group on the C2 of the cyclopentane binds to the C11 of the cyclohexene forming a tetrahydropyran ring. The shifted OH-group at C9 is lost during the reaction. An acetyltransferase (encoded by TRI101) catalyzes the acetylation of the C3 OH-group of isotrichodermol forming isotrichdermin.

Isotrichodermin is converted to 15-decalonecitrin due to a substitution (encoded by TRI11) of one hydrogen by one hydroxyl at C15 which is then acetylated under help of TRI3. The same substitution and following acetylation reactions occur at C4 again under the control of TRI13 and TRI7. TRI1 in F.sporotrichiodies further catalyzes the addition of a fourth OH-group at C8 and a fifth OH-group at C7 at which then the hydrogen is eliminated and a keto group forms.

In a last step an esterase controlled by TRI8 catalyzes the deacetylation at C3, C4 and C15 resulting in the end product nivalenol. A partly alternative synthesis can occur when the catalysts TRI1 and TRI13, TRI7 are used in opposite order. Then the addition of the hydroxyl groups at C7 and C8 controlled by TRI1 are happening with calonectrin as reactant. In this reaction 7,8-dihydroxycalonectrin is formed. It further reacts spontaneously to 3,15-acetyl-deoxynivalenol via elimination of a hydrogen and formation of a keto-group at C8. The addition of a hydroxyl group at C4 controlled by TRI13 occurs and is acetylated under the help of TRI7. This yields 3,4,15-triacetylnivalenol (3,4,15-triANIV) from which it is than again the same synthesis as described above.[9]

作用機序

ニバレノールは、多くの異なる生物学的経路に変化を齎す。最もよく知られており、おそらく重要なのはNF-κB経路である。NF-κBは、ほとんどのヒトの細胞に存在する転写因子で、ゲノムDNA上の特定のモチーフに結合する事で、標的遺伝子の発現を制御する。ニバレノールは、免疫系の重要な制御分子であるサイトカインの発現を変化させる事が、in vitro の実験で明らかになっている。ニバレノールは、炎症のメディエーターであるIL-8の分泌を誘導した。NF-κB阻害剤を投与すると、IL-8の分泌量が減少した。ニバレノールの影響を受けるもう一つの重要な因子はMCP-1/CCL2で、このサイトカインは単球細胞の運動性調節の役割を果たしている。ニバレノールはCCL2の分泌を低下させ、その結果、単球の移動性を低下させる。この事は、ニバレノールの免疫抑制作用の一部を説明している。また、この効果はNF-κBを阻害すると減少する事から、ニバレノールとNF-κBが相互に作用して細胞に影響を与えている事が判る[11][12]。

デオキシニバレノールは、免疫関連のメッセンジャー分子でもあるケモカインの分泌を誘導するが、ニバレノールはその分泌を抑制する事が示された[13][14]。また、ニバレノールはマクロファージの炎症性遺伝子の発現を上昇させ、異なる細胞種に混合して作用する事が判明した。これは細胞毒性レベルでも同じである[15]。

ニバレノールの細胞毒性のもう一つのメカニズムは、アポトーシスによる細胞毒性であり、ニバレノールは、しばしば共存するマイコトキシンのパートナーであるデオキシニバレノールよりも毒性が強く、DNA損傷とアポトーシスを引き起こすことでその効果を発揮する[16]。また、ニバレノールはヒト白血球の増殖に影響を与えることが知られている。ニバレノールは、ヒト白血球の増殖率を用量依存的に変化させることが示されている。低濃度では白血球の増殖が促進され、高濃度では用量依存的に増殖が抑制されることが知られている[17]。

代謝

Nivalenol in mice is not only metabolized through the liver but also, for a lesser part through microbial detoxification in the intestines. Thereby especially the epoxide group as most toxic part of the molecule is degraded. This happens by eliminating the oxygen of the epoxide group resulting in a double carbon-carbon bond between C12 and C13. This double bond is nonpolar and very stable leading to a less reactive form of nivalenol called de-epoxynivalenol. The de-epoxinated nivalenol gained is therefore much less toxic, same as every de-epoxinated trichodiene, and can be segregated into the urine without having much toxic effects anymore (nearly non-toxic).

In the urine of tested mice and pigs 80% of the de-epoxidated compound and only 7% of the actual nivalenol were found showing a high metabolising rate of the trichodienes.[5] Thereby a low concentration of nitrogen in low proteins and urea were observed whereas the cholesterol concentration was observed to be higher than normal. This suggests that nivalenol is present and later degraded in the liver as the liver is responsible for the segregation of cholesterol into the bloodstream. The higher amount of cholesterol in the blood leads then to a higher amount of filtered cholesterol by the kidneys and eventually to an increased concentration in the urea.[10][18]

The lowered concentration of amides is assumed to be caused in the degradation process of the reactive epoxide group. Therefore, the epoxides are often found to react with amides or amide groups by adding a hydroxyl group at a primary or secondary amine. As a consequence the epoxide group is degraded and less nitrogen is present for the synthesis of proteins or urea.

家畜等への影響

As nivalenol is a mycotoxic product of certain Fusarium species it is often found in infected wheat and grain. As unprocessed wheat and grain product are often used as feed for livestock animals these are at a higher risk of nivalenol intake.

Toxicity studies in swine that received a dose of 0.05 mg nivalenol/kg body weight twice daily showed no lethal effects. Most nivalenol was secreted with the feces and did not reach the bloodstream despite the fact that there was still nivalenol upstage over the intestines after 16 hours of feeding. There were further no nivalenol metabolites found in feces or urine within the first three days.[19] After a week of exposure to 2.5 or 5 mg nivalenol kg bw twice a day a microbiological adaptation was seen as nivalenol metabolites (de-epoxidated nivalenol) could be found in feces and urine.

In rats and mice nivalenol showed to be toxic with adverse effects of growth retardation and leukopenia already noticed at lowest doses of 0.7 mg/kg bw per day. Lethal doses were dependent on the route of administration/intake of nivalenol. As nivalenol is normally taken up with feed the LD50 of oral administration which is 38.9 mg/kg bw per day in mice and 19.5 mg/kg bw per day in rats can be used as standard. The LD50 of intravenous, intraperitoneal and subcutaneous (SC) is between 7 and 7.5 mg/kg bw per day.[20]

毒性の詳細

The toxicity of nivalenol in humans is for the most parts unknown yet, but it was investigated in mice, rats and hamster cells. Thereby the toxicity was divided in the following topics: acute/subacute, subchronic, chronic and carcinogenicity, genotoxicity, developmental toxicity studies and studies on reproduction, immunotoxicity/hematotoxycity and effects on nervous system.

Acute/subacute toxicity

The oral LD50 of nivalenol was found to be 38.9 mg/kg bw in mice whereas the intraperitonal, subcutaneous and intravenous routes of exposure gave LD50 values of 5–10 mg/kg bw. In mice already within 3 days the most deaths occurred after oral exposure through marked congestion and haemorrhage in intestine, in acute toxicity also lymphoid organs are included. Nivalenol given over time periods of 24 days in lower doses (ca. 3,5 mg/kg bw) showed significant erythropenia and slight leukopenia.[20]

Subchronic toxicity

The subchronic toxicity was tested by feeding mice with a daily dose of 0 to 3.5 mg nivalenol/ kg bw for 4 or 12 weeks. The observations after 4 weeks were reduced body weight and food consumption. The reduction in body weight can be explained by statistical decrease in organ weight in thymus, spleen and kidneys. Whereas the consumption time was less for female mice in comparison to male mice. After 12 weeks the toxin consumption resulted in reduction of relative organ weight in both males and females. Hereby only the liver was affected and no histopathological changes were observed.[20]

Chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity

Female mice were fed with different doses of nivalenol (0, 0.7, 1.4 or 3.5 mg nivalenol /kg bw) for one or two years to investigate whether nivalenol is chronic toxic and/or carcinogenic. Also during this study a decrease in body weight and feed consumption was observed. The absolute weight of both liver and kidney was decreased through the two highest doses. The mice fed for one year with nivalenol (also with the lower doses) were affected with severe leukopenia whereas the mice fed for two years had no differences in count of white blood cells. Also "no histopathological changes including tumours were found in liver, thymus, spleen, kidneys, stomach, adrenal glands, pituitary glands, ovaries, bone marrow, lymph node, brain and small intestines with or without Peyer's patch".[20] The lowest doses (0.7 mg nivalenol /kg bw) inhibited the growth and caused leukopenia. "A no observable adverse effect level (NOAEL) could not be derived from these studies. IARC (1993) concluded that there is inadequate evidence of carcinogenicity of nivalenol in experimental animals. No human data were available. The overall conclusion was that the carcinogenicity was not classifiable (group 3)".[20]

Genotoxicity

It was found that nivalenol effects the genes of Chinese hamster V79 (CHO) cells by slightly increased frequencies of chromosomal aberrations and sister chromatid exchange. The DNA was damaged in CHO cells as well as in mice. In mice (given 20 mg nivalenol /kg bw orally or 3.7 mg /kg bw ip) the DNA of kidney, bone marrow, stomach, jejunum and colon was damaged. The DNA of the thymus and liver was not effected. In organs with DNA damage no necrotic changes were found upon histopathological examination. It can be concluded that an adequate evaluation of the genotoxicity is not allowed based on the available data.[20]

Developmental toxicity and studies on reproduction

For developmental and reproduction studies pregnant mice were injected with different amounts of purified nivalenol on days 7–15 of gestation and for one additional study with mouldy rice containing nivalenol. The studies showed that the toxin is embryotoxic in mice. No evidence of teratogenicity was given. "The LOAEL in reproduction studies with nivalenol given by oral exposure was stated to be 1.4 mg/kg bw given in the feed throughout gestation and 5 mg/kg bw when given by gavage on days 7–15".[20] Data from other species and on reproductive effects in adult males and females are not provided yet.[20]

Immunotoxicity/haematotoxicity

Acute toxicity of nivalenol induces bone marrow toxicity and toxicity of lymphoid organs. Long-term exposure may result in erythropenia and/or leukopenia. In mice it was also observed that nivalenol increased the presence of serum IgA, "accompanied by immunopathological changes in kidneys analogous to human IgA-nephropathy".[20] The blastogenesis in cultured human lymphocytes, proliferation of human male and female lymphocytes stimulated with phytoheamagglutin and pokeweed and immunoglobulin production induced by pokeweed, are inhibited by nivalenol. The effects of nivalenol are in the same range as same doses of deoxynivalenol, whereas the T-2 toxin are 100 fold more toxic. An additive effect is gained by combination of nivalenol with T-2 toxin, 4,15-diacetoxyscirpenol or deoxynivalenol.[20]

Effects on nervous system

About the nervous system no data has been provided yet.[20]

関連項目

ニバレノール、デオキシニバレノール、T2 トキシンは、何れも真菌(Fusarium など)に天然に存在する類縁化合物である[10]。

出典

- ^ a b “Nivalenol”. Cayman Chemical. 2018年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “Nivalenol”. PubChem. 2018年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “Nivalenol”. Safety Data Sheet. 2018年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Scientific Opinion on risks for animal and public health related to the presence of nivalenol in food and feed”. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Journal 11 (6): 1–5. (2013).

- ^ a b c Hedman, R.; Pettersson, H.; Lindberg, J.E. (2009). “Absorption and metabolism of nivalenol in pigs”. Archiv für Tierernaehrung 50-1 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1080/17450399709386115. PMID 9205733.

- ^ EFSA CONTAM Panel (EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain) (2013). “Scientific Opinion on risks for animal and public health related to the presence of nivalenol in food and feed”. EFSA Journal 11 (6): 3262–119. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2013.3262.

- ^ Gupta, R. C., ed (2015). Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents. Academic Press. pp. 353–369. ISBN 9780128001592

- ^ Venkataramana, M.; Chandranayaka, S.; Prakash, H. S.; Niranja, R. (2014). “na, S. (2014). Mycotoxins Relevant to Biowarfare and Their Detection”. Biological Toxins and Bioterrorism: 22. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6645-7_32-1.

- ^ a b c McCormick, S. P.; Stanley, A. M.; Stover, N. A.; Alexander, N. J. (2011). “Trichothecenes: From Simple to Complex Mycotoxins”. Toxins 3 (7): 802–814. doi:10.3390/toxins3070802. PMC 3202860. PMID 22069741.

- ^ a b c d Sidell, F. R.; Takafuji, E. T.; Franz, D. R. (1997). Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare. United States Government Printing. pp. 662–664. ISBN 978-9997320919

- ^ US National Library of Medicine. “HSDB: Hazardous Substances Data Bank”. 2018年3月23日閲覧。

- ^ Deshmaneand, S. L.; Kremlev, S.; Amini, S.; Sawaya, B. E. (2009). “Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1): An Overview”. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research 29 (6): 313–326. doi:10.1089/jir.2008.0027. PMC 2755091. PMID 19441883.

- ^ Nagashima, H. (2012). “Environ Toxicol Pharmacol”. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 34 (3): 1014–7. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2012.07.008. PMID 22964157.

- ^ Deshmane, S. L. (2009). “Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview.”. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research 29 (6): 313–326. doi:10.1089/jir.2008.0027. PMC 2755091. PMID 19441883.

- ^ Sugita-Konishi, Y.; Pestka, J. J. (2001). “Differential upregulation of TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-8 production by deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin) and other 8-ketotrichothecenes in a human macrophage model.”. Toxicol Environ Health A 64 (8): 619–36. doi:10.1080/152873901753246223. PMID 11766169.

- ^ Minervini, F. (2004). “Toxicity and apoptosis induced by the mycotoxins nivalenol, deoxynivalenol and fumonisin B1 in a human erythroleukemia cell line.”. Toxicol in Vitro 18 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1016/S0887-2333(03)00130-9. PMID 14630058.

- ^ Taranu, I. (2010). “Comparative aspects of in vitro proliferation of human and porcine lymphocytes exposed to mycotoxins.”. Arch Anim Nutr. 64 (5): 383–93. doi:10.1080/1745039X.2010.492140. PMID 21114234.

- ^ Sundstøl Eriksen, G.; Pettersson, H.; Lundh, T. (2004). “Comparative cytotoxicity of deoxynivalenol, nivalenol, their acetylated derivatives and de-epoxy metabolites”. Food and Chemical Toxicology 42 (4): 619–624. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2003.11.006. PMID 15019186.

- ^ Pettersson, H.; Hedman, R. (1997). “Toxicity and metabolism of nivalenol in farm animals”. Cereal Research Communications (Akadémiai Kiadó) 25-3 (3): 423–427. doi:10.1007/BF03543746.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k “Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on Fusarium Toxins Part 41: Nivalenol”. Scientific Committee on Food: 2–6. (2000).