LIG3

LIG3またはDNAリガーゼIII(DNA ligase 3)は、ヒトではLIG3遺伝子にコードされる酵素である[5][6]。ヒトのLIG3遺伝子はATP依存性DNAリガーゼをコードし、二本鎖DNA中で途切れたホスホジエステル骨格を閉じる役割を果たす。

真核生物のATP依存性DNAリガーゼには3つのファミリーが存在する[7]。これらの酵素はいずれも、(i) 酵素-アデニル酸共有結合中間体の形成、(ii) DNAのニックの5'末端へのアデニル酸基の転移、(iii) ホスホジエステル結合の形成、という共通した三段階の反応機構を利用する。ほぼ全ての真核生物に存在するLIG1やLIG4ファミリーのメンバーとは異なり、LIG3ファミリーのメンバーの分布は比較的狭い範囲に限られている[8]。LIG3遺伝子には、選択的翻訳開始部位や選択的スプライシング機構によって、いくつかの異なるポリペプチドがコードされている。

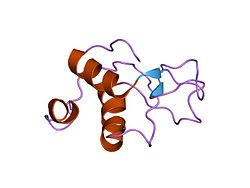

構造、DNA結合と触媒活性[編集]

真核生物のATP依存性DNAリガーゼには、DNA結合ドメイン、アデニル化ドメイン、オリゴヌクレオチド/オリゴ糖結合フォールド(OBフォールド)ドメインの3つのドメインが含まれる。酵素が二本鎖DNA中のニック部分に結合すると、これらのドメインはDNA二本鎖を取り囲み、各ドメインがDNAとの接触を行う。LIG3の触媒領域とニック含有DNAとの複合体構造がX線結晶構造解析によって決定されており、その構造はニック含有DNAに結合したLIG1の触媒領域の構造と顕著に類似している[9]。LIG3に固有の特徴はN末端にジンクフィンガーが存在することであり、この部分はPARP1のN末端に位置する2つのジンクフィンガーと類似している[10]。PARP1のジンクフィンガーと同様、LIG3のジンクフィンガーはDNA鎖の切断部への結合に関与している[10][11][12]。ジンクフィンガーはDNA結合ドメインと協働してDNA結合モジュールを形成し、さらにアデニル化ドメインとOBフォールドドメインも2つ目のDNA結合モジュールを形成する[13]。Ellenbergerらによって提唱されたジャックナイフモデル[13]では、ジンクフィンガー-DNA結合ドメインモジュールは、鎖切断部の末端の性質とは無関係に一本鎖の切断部に結合する、鎖切断センサーとして作用するとされる。切断部のライゲーションが可能である場合には、ライゲーション可能なニックに対して特異的に結合するアデニル化ドメイン-OBフォールドドメインモジュールへ切断部は受け渡される。LIG1やLIG4と比較して、LIG3はDNA二本鎖の分子間の結合活性が最も高い酵素である[14]。この活性は主にLIG3のジンクフィンガーに依存しており、LIG3の2つのDNA結合モジュールが2つの二本鎖DNAの末端に同時に結合する可能性を示唆している[9][13]。

選択的スプライシング[編集]

選択的翻訳開始や選択的スプライシング機構によって、LIG3の触媒領域に隣接するN末端、C末端配列は変化する[15][16]。選択的スプライシング機構によって、LIG3αのC末端領域はより短く正に帯電した核局在シグナルとして機能する配列に置き換わる。このスプライシングバリアントはLIG3βと呼ばれ、これまでのところオスの生殖細胞でのみ検出されている[16]。その精子形成時の発現パターンに基づくと、LIG3βは減数分裂時の組換えまたは半数体精子におけるDNA修復に関与している可能性が高いが、このことは明確に実証されたわけではない。LIG3のmRNAには複数の翻訳開始部位が存在し、オープンリーディングフレーム(ORF)内部に位置するATGコドンが選択的に利用されるものの、ORFの最初に位置するATGコドンからの翻訳開始も行われ、それによってN末端にミトコンドリア標的化配列を持つポリペプチドが合成される[15][17][18]。

細胞機能[編集]

上述したように、LIG3αのmRNAは核型とミトコンドリア型のLIG3αをコードしている。核型のLIG3αはDNA修復タンパク質XRCC1との安定な複合体として存在し、機能する[19][20]。これらのタンパク質はC末端のBRCTドメインを介して相互作用する[16][21]。XRCC1は酵素活性を持たないが、塩基除去修復や一本鎖切断修復に関与する多数のタンパク質と相互作用する足場タンパク質として作用しているようである。これらの経路にXRCC1が関与していることは、XRCC1欠損細胞の表現型とも一致する[19]。核型のLIG3αとは対照的に、ミトコンドリア型のLIG3αはXRCC1非依存的に機能する。XRCC1はミトコンドリアには存在しない[22]。核型のLIG3αは細胞質でXRCC1と複合体を形成し、XRCC1の核局在シグナルによって核へ標的化されるようである[23]。ミトコンドリア型のLIG3αもXRCC1と相互作用するが、LIG3αのミトコンドリア標的化配列の活性はXRCC1の核局在シグナルの活性よりも高く、ミトコンドリア型LIG3αがミトコンドリア膜を通過する際にLIG3α/XRCC1複合体は破壊されると考えられる。

LIG3遺伝子はミトコンドリアにおける唯一のDNAリガーゼをコードしているため、LIG3遺伝子の不活性化はミトコンドリアDNAの喪失、そしてミトコンドリアの機能喪失をもたらす[24][25][26]。Lig3遺伝子が不活性化された線維芽細胞はウリジンとピルビン酸を補充した培地で増殖することができるが、これらの細胞はミトコンドリアDNAを欠いている[27]。生理的条件下ではミトコンドリア型LIG3は過剰量存在しているようであり、その量が100分の1に減少してもミトコンドリアDNAは正常なコピー数が維持される[27]。ミトコンドリアDNA代謝においてLIG3αが果たしている必須の役割は、大腸菌Escherichia coliのNAD依存性DNAリガーゼなど、他のDNAリガーゼによって代替することができる[24][26]。そのため、核型LIG3αを欠く生存可能な細胞を作製することができる。DNA複製時の岡崎フラグメントの連結に主要な役割を果たしているのはLIG1であるが、LIG1の活性が喪失したり低下したりした細胞ではLIG3α/XRCC1複合体によってDNA複製を完了させることができることが明らかになっている[24][26][28][29]。生化学的研究や細胞生物学的研究によってLIG3α/XRCC1複合体と除去修復や一本鎖切断修復とが関連付けられている[30][31][32][33]ことを考えると、核型LIG3αを欠く細胞でDNA損傷試薬に対する感受性の有意な増加がみられないことは驚くべきことである[24][26]。これらのことは、こうした核内DNA修復経路におけるLIG1とLIG3αの間に大きな機能的冗長性があることを示唆している。哺乳類細胞では、DNA二本鎖切断の大部分はLIG4依存的な非相同末端結合(NHEJ)経路によって修復される[34]。一方LIG3αは、染色体転座を生み出すマイナーな代替的NHEJ経路(alt-NHEJ経路、MMEJ経路)に関与している[35][36]。他の核内DNA修復経路と異なり、このalt-NHEJ経路におけるLIG3αの役割はXRCC1に依存していないようである[37]。

臨床的意義[編集]

LIG1遺伝子やLIG4遺伝子とは異なり[38][39][40][41]、LIG3遺伝子の遺伝性変異はヒト集団では同定されていない。しかしながら、LIG3αはがんや神経変性疾患への間接的な関与が示唆されている。がんではLIG3αは高頻度で過剰発現しており、DNA二本鎖切断修復のalt-NHEJ経路に対する依存性が高い細胞を同定するためのバイオマーカーとして機能する[42][43][44][45]。LIG3はエラーが生じやすい二本鎖切断修復経路であるalt-NHEJ経路に必要な6つの酵素のうちの1つであり[46]、慢性骨髄性白血病[45]、多発性骨髄腫[47]、乳がん[43]でアップレギュレーションされている。alt-NHEJ経路の活性の上昇はゲノム不安定性を引き起こして疾患の進行を駆動するとともに、がん細胞特異的な治療戦略開発における新規標的ともなる[43][44]。神経変性疾患においては、LIG3αと直接相互作用したり、XRCC1を介して間接的に相互作用したりするタンパク質をコードするいくつかの遺伝子の変異が同定されている[48][49][50][51][52]。そのため、LIG3αが関与するDNAトランザクションは神経細胞の生存の維持に重要な役割を果たしているようである。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000005156 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020697 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Entrez Gene: Ligase III, DNA, ATP-dependent”. 2012年3月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Structure and function of the DNA ligases encoded by the mammalian LIG3 gene”. Gene 531 (2): 150–7. (December 2013). doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.061. PMC 3881560. PMID 24013086.

- ^ “Eukaryotic DNA ligases: structural and functional insights”. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77: 313–38. (2008). doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.123941. PMC 2933818. PMID 18518823.

- ^ “DNA ligase III: a spotty presence in eukaryotes, but an essential function where tested”. Cell Cycle 10 (21): 3636–44. (November 2011). doi:10.4161/cc.10.21.18094. PMC 3266004. PMID 22041657.

- ^ a b “Human DNA ligase III recognizes DNA ends by dynamic switching between two DNA-bound states”. Biochemistry 49 (29): 6165–76. (July 2010). doi:10.1021/bi100503w. PMC 2922849. PMID 20518483.

- ^ a b “DNA ligase III is recruited to DNA strand breaks by a zinc finger motif homologous to that of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Identification of two functionally distinct DNA binding regions within DNA ligase III”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 (31): 21679–87. (July 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.31.21679. PMID 10419478.

- ^ “Physical and functional interaction between DNA ligase IIIalpha and poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 in DNA single-strand break repair”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 23 (16): 5919–27. (August 2003). doi:10.1128/MCB.23.16.5919-5927.2003. PMC 166336. PMID 12897160.

- ^ “The DNA ligase III zinc finger stimulates binding to DNA secondary structure and promotes end joining”. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (18): 3558–63. (September 2000). doi:10.1093/nar/28.18.3558. PMC 110727. PMID 10982876.

- ^ a b c “Two DNA-binding and nick recognition modules in human DNA ligase III”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 (16): 10764–72. (April 2008). doi:10.1074/jbc.M708175200. PMC 2447648. PMID 18238776.

- ^ “Interactions of the DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 complex with DNA ends and the DNA-dependent protein kinase”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (34): 26196–205. (August 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M000491200. PMID 10854421.

- ^ a b “The human DNA ligase III gene encodes nuclear and mitochondrial proteins”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 19 (5): 3869–76. (May 1999). doi:10.1128/MCB.19.5.3869. PMC 84244. PMID 10207110.

- ^ a b c “An alternative splicing event which occurs in mouse pachytene spermatocytes generates a form of DNA ligase III with distinct biochemical properties that may function in meiotic recombination”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 17 (2): 989–98. (February 1997). doi:10.1128/MCB.17.2.989. PMC 231824. PMID 9001252.

- ^ “Molecular cloning and expression of human cDNAs encoding a novel DNA ligase IV and DNA ligase III, an enzyme active in DNA repair and recombination”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 15 (6): 3206–16. (June 1995). doi:10.1128/mcb.15.6.3206. PMC 230553. PMID 7760816.

- ^ “Mammalian DNA ligase III: molecular cloning, chromosomal localization, and expression in spermatocytes undergoing meiotic recombination”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 15 (10): 5412–22. (October 1995). doi:10.1128/MCB.15.10.5412. PMC 230791. PMID 7565692.

- ^ a b “An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 14 (1): 68–76. (January 1994). doi:10.1128/MCB.14.1.68. PMC 358357. PMID 8264637.

- ^ “Characterization of the XRCC1-DNA ligase III complex in vitro and its absence from mutant hamster cells”. Nucleic Acids Res. 23 (23): 4836–43. (December 1995). doi:10.1093/nar/23.23.4836. PMC 307472. PMID 8532526.

- ^ “XRCC1 protein interacts with one of two distinct forms of DNA ligase III”. Biochemistry 36 (17): 5207–11. (April 1997). doi:10.1021/bi962281m. PMID 9136882.

- ^ “Mitochondrial DNA ligase III function is independent of Xrcc1”. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (20): 3880–6. (October 2000). doi:10.1093/nar/28.20.3880. PMC 110795. PMID 11024166.

- ^ “XRCC1 phosphorylation by CK2 is required for its stability and efficient DNA repair”. DNA Repair (Amst.) 9 (7): 835–41. (July 2010). doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.04.008. PMID 20471329.

- ^ a b c d “DNA ligase III is critical for mtDNA integrity but not Xrcc1-mediated nuclear DNA repair”. Nature 471 (7337): 240–4. (March 2011). doi:10.1038/nature09773. PMC 3079429. PMID 21390131.

- ^ “Antisense-mediated decrease in DNA ligase III expression results in reduced mitochondrial DNA integrity”. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 (3): 668–76. (February 2001). doi:10.1093/nar/29.3.668. PMC 30390. PMID 11160888.

- ^ a b c d “Crucial role for DNA ligase III in mitochondria but not in Xrcc1-dependent repair”. Nature 471 (7337): 245–8. (March 2011). doi:10.1038/nature09794. PMC 3261757. PMID 21390132.

- ^ a b Shokolenko, IN; Fayzulin, RZ; Katyal, S; McKinnon, PJ; Alexeyev, MF (Sep 13, 2013). “Mitochondrial DNA ligase is dispensable for the viability of cultured cells but essential for mtDNA maintenance”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 288 (37): 26594–605. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.472977. PMC 3772206. PMID 23884459.

- ^ “Functional redundancy between DNA ligases I and III in DNA replication in vertebrate cells”. Nucleic Acids Research 40 (6): 2599–610. (March 2012). doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1024. PMC 3315315. PMID 22127868.

- ^ “Partial complementation of a DNA ligase I deficiency by DNA ligase III and its impact on cell survival and telomere stability in mammalian cells”. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 69 (17): 2933–49. (September 2012). doi:10.1007/s00018-012-0975-8. PMC 3417097. PMID 22460582.

- ^ “Involvement of XRCC1 and DNA ligase III gene products in DNA base excision repair”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (38): 23970–5. (September 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.38.23970. PMID 9295348.

- ^ “Translocation of XRCC1 and DNA ligase III-alpha from centrosomes to chromosomes in response to DNA damage in mitotic human cells”. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 (1): 422–9. (2005). doi:10.1093/nar/gki190. PMC 546168. PMID 15653642.

- ^ “Reconstitution of DNA base excision-repair with purified human proteins: interaction between DNA polymerase beta and the XRCC1 protein”. EMBO Journal 15 (23): 6662–70. (December 1996). doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01056.x. PMC 452490. PMID 8978692.

- ^ “Sealing of chromosomal DNA nicks during nucleotide excision repair requires XRCC1 and DNA ligase III alpha in a cell-cycle-specific manner”. Molecular Cell 27 (2): 311–23. (July 2007). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.014. PMID 17643379.

- ^ Lieber MR (2010). “The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway”. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79: 181–211. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. PMC 3079308. PMID 20192759.

- ^ “DNA ligase III as a candidate component of backup pathways of nonhomologous end joining”. Cancer Res. 65 (10): 4020–30. (May 2005). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3055. PMID 15899791.

- ^ Haber, James E, ed (June 2011). “DNA ligase III promotes alternative nonhomologous end-joining during chromosomal translocation formation”. PLOS Genet. 7 (6): e1002080. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002080. PMC 3107202. PMID 21655080.

- ^ “Robust chromosomal DNA repair via alternative end-joining in the absence of X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1 (XRCC1)”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109 (7): 2473–8. (February 2012). doi:10.1073/pnas.1121470109. PMC 3289296. PMID 22308491.

- ^ “Analysis of DNA ligase IV mutations found in LIG4 syndrome patients: the impact of two linked polymorphisms”. Human Molecular Genetics 13 (20): 2369–76. (October 2004). doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh274. PMID 15333585.

- ^ “DNA ligase IV mutations identified in patients exhibiting developmental delay and immunodeficiency”. Molecular Cell 8 (6): 1175–85. (December 2001). doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00408-7. PMID 11779494.

- ^ “Identification of a defect in DNA ligase IV in a radiosensitive leukaemia patient”. Curr. Biol. 9 (13): 699–702. (July 1999). doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80311-X. PMID 10395545.

- ^ “Mutations in the DNA ligase I gene of an individual with immunodeficiencies and cellular hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents”. Cell 69 (3): 495–503. (May 1992). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90450-Q. PMID 1581963.

- ^ “Rational design of human DNA ligase inhibitors that target cellular DNA replication and repair”. Cancer Res. 68 (9): 3169–77. (May 2008). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6636. PMC 2734474. PMID 18451142.

- ^ a b c “Targeting abnormal DNA repair in therapy-resistant breast cancers”. Molecular Cancer Research 10 (1): 96–107. (2012). doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0255. PMC 3319138. PMID 22112941.

- ^ a b “Targeting abnormal DNA double-strand break repair in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant chronic myeloid leukemias”. Oncogene 32 (14): 1784–93. (April 2013). doi:10.1038/onc.2012.203. PMC 3752989. PMID 22641215.

- ^ a b “Up-regulation of WRN and DNA ligase III-alpha in chronic myeloid leukemia: consequences for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks”. Blood 112 (4): 1413–23. (August 2008). doi:10.1182/blood-2007-07-104257. PMC 2967309. PMID 18524993.

- ^ “Homology and enzymatic requirements of microhomology-dependent alternative end joining”. Cell Death Dis 6 (3): e1697. (2015). doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.58. PMC 4385936. PMID 25789972.

- ^ “Deregulation of DNA double-strand break repair in multiple myeloma: implications for genome stability”. PLOS ONE 10 (3): e0121581. (2015). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121581. PMC 4366222. PMID 25790254.

- ^ “The neurodegenerative disease protein aprataxin resolves abortive DNA ligation intermediates”. Nature 443 (7112): 713–6. (October 2006). doi:10.1038/nature05164. PMID 16964241.

- ^ “Early-onset ataxia with ocular motor apraxia and hypoalbuminemia is caused by mutations in a new HIT superfamily gene”. Nature Genetics 29 (2): 184–8. (October 2001). doi:10.1038/ng1001-184. PMID 11586299.

- ^ “The gene mutated in ataxia-ocular apraxia 1 encodes the new HIT/Zn-finger protein aprataxin”. Nature Genetics 29 (2): 189–93. (October 2001). doi:10.1038/ng1001-189. PMID 11586300.

- ^ “Defective DNA single-strand break repair in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy-1”. Nature 434 (7029): 108–13. (March 2005). doi:10.1038/nature03314. PMID 15744309.

- ^ “Mutations in PNKP cause microcephaly, seizures and defects in DNA repair”. Nature Genetics 42 (3): 245–9. (March 2010). doi:10.1038/ng.526. PMC 2835984. PMID 20118933.