ビカルタミド

| |

| |

| IUPAC命名法による物質名 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 臨床データ | |

| 販売名 | Casodex, others |

| Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697047 |

| ライセンス | US FDA:リンク |

| 胎児危険度分類 | |

| 法的規制 |

|

| 投与経路 | By mouth[1] |

| 薬物動態データ | |

| 生物学的利用能 | Well-absorbed; absolute bioavailability unknown[2] |

| 血漿タンパク結合 | Racemate: 96.1%[1] (R)-Isomer: 99.6%[1] (Mainly to albumin)[1] |

| 代謝 | Liver (extensively):[3][4] • Hydroxylation (CYP3A4) • Glucuronidation (UGT1A9) |

| 代謝物質 | • Bicalutamide glucuronide • Hydroxybicalutamide • Hydroxybicalutamide gluc. (All inactive)[1][3][5][6] |

| 作用発現 | Unknown[7] |

| 作用持続時間 | Unknown[7] |

| 識別 | |

| 別名 | ICI-176,334; ZD-176,334 |

| 化学的データ | |

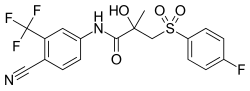

| 化学式 | C18H14F4N2O4S |

| 分子量 | 430.37 g·mol−1 |

| |

| 物理的データ | |

| 融点 | 191 - 193 °C (376 - 379 °F) (experimental) |

| 沸点 | 650 °C (1,202 °F) (predicted) |

| 水への溶解量 | 0.005 mg/mL (20 °C) |

ビカルタミド(Bicalutamide)は、カソデックス(Casodex)など商品名で販売されている主に前立腺癌の治療に用いられる抗アンドロゲン薬である[8]。通常、ゴナドトロピン放出ホルモン(GnRH)アナログまたは睾丸摘出手術と併用して進行性前立腺癌の治療に用いられる[8][9][10]。ビカルタミドは、女性の過度の発毛[11]、トランスジェンダーの女性の女性化ホルモン療法の構成要素[12]、男児の思春期早発症の治療[13]、男性の持続勃起症の予防にも用いられる[14]。投与法は経口である[8]。

男性に見られる一般的な副作用には、乳房の肥大、乳房の圧痛、ほてりなどが挙げられる[8]。男性に見られるその他の副作用には、女性化と性機能障害がある[15]。ビカルタミドは女性にはほとんど副作用を引き起こさないようであるが、女性への使用について食品医薬品局(FDA)は推奨していない[8][16]。日本では女性には禁忌である[17]。妊娠中の人への投与は胎児に害を及ぼす可能性がある[8]。ビカルタミドは、約1%の人に肝酵素の上昇を引き起こす[18][19]。稀に、肝障害[8]、肺毒性[2]、光線過敏症の症例に関連している[20][21]。肝臓への悪影響のリスクは少ないが、治療中は肝機能を監視することが勧められている[8]。

ビカルタミドは、非ステロイド系抗アンドロゲン薬(NSAA)に属する医薬品の一つである[2]。ビカルタミドの作用機序は、アンドロゲンホルモンであるテストステロンとジヒドロテストステロン(DHT)の生物学的標的であるアンドロゲン受容体(AR)を遮断することによって機能する[22]。アンドロゲンレベルを下げることはない[2]。この医薬品は男性にエストロゲンのような効果をもたらす可能性がある[23][24][25]。ビカルタミドは吸収され易く、食物によって吸収率が左右されることはない[1]。ビカルタミドの消失半減期は約1週間である[8]。血液脳関門を通過すると考えられ、体と脳の両方に影響を与える[1]。

ビカルタミドは1982年に特許を取得し、1995年に医療用として承認された[26]。日本では1999年3月に承認された[27]:表紙。WHO必須医薬品モデル・リストに収載されている[28]。日本でも後発医薬品として入手可能である[29]。開発途上国の卸売り価格は1か月分で約7.07 - 144.22米ドルである[30]。米国では、1か月分で10米ドル以上の費用が掛かる[31]。ビカルタミドは先進国を含む80以上の国で販売されている[32][33][34]。ビカルタミドは、前立腺癌の治療に最も広く使用されている抗アンドロゲンであり、何百万人もの前立腺癌疾患の男性に処方されている[35][36][37][38]。

効能・効果[編集]

日本で承認されている効能・効果は「前立腺癌」であり、併用薬・併用療法に制限はない[17]。除睾術と併用されたり単剤で用いられたりしている[39][40]。

米国などではビカルタミドは、主に以下の効能・効果で承認されている[41]。

- 男性における転移性前立腺癌(mPC)に対する性腺刺激ホルモン放出ホルモン(GnRH)アナログ製剤または外科的去勢との併用療法[3][18][42]

- 男性における局所進行性前立腺癌(LAPC)の単剤療法(米国では未承認)[1][3][19][43]

また、ビカルタミドは以下のような適応症でも採用されている(非承認)。

- 男性におけるGnRHアゴニスト治療開始時のテストステロン・フレアの影響の軽減[44][45]

- 女性のにきび、脂漏、多毛、頭皮脱毛などのアンドロゲン依存性の皮膚・毛髪疾患、および女性の多嚢胞性卵巣症候群(PCOS)によるテストステロン高値。避妊用ピル併用[11][46][47][48][49][50][51]。

- トランスジェンダー女性に対する女性化ホルモン療法。エストロゲン併用[12][52][53][54][55][56][57]。

- 男児の末梢性思春期早発症、特に家族性男性限定思春期早発症(精巣中毒症)の場合。アナストロゾールなどのアロマターゼ阻害剤併用[13][18][58][59][60][61][62][63]。

- 男性の持続勃起症[2][14][64][65][66][67][68]

この薬は以下の適応症が示唆されているが、有効性は不明である。

これらの用途の詳細については、英語版「Medical uses of bicalutamide」を参照

禁忌[編集]

ビカルタミドは日本では、小児と女性に禁忌とされている[17]。また、米国では妊娠カテゴリーX(妊娠禁忌)[18]、オーストラリアでは妊娠カテゴリーD(2番目に制限されたランク)[75]に分類されている。すなわち、妊娠中の女性には禁忌であり、性的に活発で妊娠する可能性のある女性は、適切な避妊法と組み合わせてのみビカルタミドを服用することが強く推奨される[76][77]。ビカルタミドが母乳中に排泄されるかどうかは不明だが、多くの薬剤は母乳中に排泄されるため、授乳中は同様にビカルタミドの治療は推奨されない[2][18]。

重度の肝機能障害を持つ人ではビカルタミドの排泄が遅くなるという証拠があり、従ってこれらの患者ではビカルタミドの循環レベルが上昇する可能性があり、注意が必要とされる。重度の肝障害では、ビカルタミドの活性型(R)エナンチオマーの排泄半減期が約1.75倍(76%増、排泄半減期は健常者で5.9日、障害者で10.4日)に増加する[19][78][79]。腎障害では、ビカルタミドの排泄半減期は変化しない[80]。

副作用[編集]

重大な副作用は、

である[17]。

5%以上の患者に乳房腫脹が現われる。

詳細は英語版「Side effects of bicalutamide」を参照。

他の抗アンドロゲン薬との比較[編集]

男女におけるビカルタミドの副作用プロファイルは、他の抗アンドロゲン薬とは異なり、比較的に良好であると考えられている[81][82][83][84]。GnRHアナログ薬や、ステロイド系抗アンドロゲン薬(SAA)である酢酸シプロテロン(CPA)と比較して、ビカルタミド単剤療法は、火照りや性機能障害の発生率および重症度が遥かに低い[82][85][86][87]。また、GnRHアナログ製剤やCPAとは異なり、ビカルタミド単剤療法は骨密度の低下や骨粗鬆症とは無縁である[82][86]。逆に、ビカルタミド単剤療法は、GnRHアナログ製剤やCPAと比較して、男性における乳房圧痛、女性化乳房 、女性化の発生率が非常に高いとされている[86]。しかし、ビカルタミドによる女性化は重度であることは稀であり、この副作用による中止率はかなり低いとされている[82][86]。こうしたビカルタミド単剤、GnRHアナログ、CPAの副作用の違いは、GnRHアナログやCPAがエストロゲンの産生を抑制するのに対し、ビカルタミド単剤はエストロゲンレベルを低下させず、むしろ増加させるという事実に起因する[86]。

ビカルタミドは、CPAと関連している抑うつや疲労などの精神神経系の副作用や、凝固変化、血栓、体液貯留、虚血性心筋症、有害な血清脂質変化などの心血管系の副作用のリスクを共有していない[87][88][89][90]。ビカルタミドは、フルタミドやCPAよりも肝毒性が、ニルタミドよりも間質性肺炎のリスクが遥かに低い[82][91][92][93][94]また、フルタミドの下痢、ニルタミドの悪心・嘔吐・視覚障害・アルコール不耐性といった特有のリスクもない[82][87]。エンザルタミドとは異なり、ビカルタミドは痙攣発作や、不安や不眠といった中枢性の副作用とは無縁である[95][96]。しかし、ビカルタミドによる肝臓の有害な変化のリスクは低いが、エンザルタミドはビカルタミドと異なり、肝酵素の上昇や肝毒性のリスクが知られていない[97][98]。ステロイド系抗アンドロゲン薬であるスピロノラクトンとは対照的に、ビカルタミドは抗鉱質コルチコイド作用を有さず[99]、そのため高カリウム血症、頻尿、脱水、低血圧、その他の関連する副作用とは無縁である[87][100][101][102]。女性では、CPAやスピロノラクトンと異なり、ビカルタミドは月経不順や無月経を起こさず、排卵や受胎能力を妨げない[46][103]。

過量投与[編集]

日本で承認されている用量は1日1回80mgである[17]。米国などでは基本的に1日1回50mgである[18]。ヒトにおけるビカルタミドの単回経口投与で、過量投与の症状が現れたり、生命を脅かすと考えられる用量は確立されていない[18][104]。臨床試験では600mg/日までの投与量で良好な忍容性が得られており[105]、ビカルタミドの吸収が飽和しているため、活性 (R)-エナンチオマーの血中循環濃度は300mg/日の投与量を超えてもそれ以上上昇しないことが注目されている[1][105]。ビカルタミドや他の第一世代のNSAA(フルタミド、ニルタミドなど)では、過量投与による生命への影響はないと考えられている[106]。79歳の男性がニルタミドを大量に過量摂取した際(13g、通常の最大臨床投与量である300mg/日の43倍)、臨床的な徴候、症状、毒性は見られず、問題は起こらなかった[107]。ビカルタミドまたはNSAAの過量投与に対する特異的な解毒剤はなく、症状がある場合はその症状に基づいて治療を行う必要がある[18][104]。

相互作用[編集]

ビカルタミドは、ほとんどがCYP3A4によって代謝される[3]。そのため、CYP3A4の阻害薬や誘導薬によって体内の濃度が変化する可能性がある[68]。しかし、ビカルタミドはCYP3A4で代謝されるにもかかわらず、150mg/日以下の用量のビカルタミドとシトクロムP450酵素活性を阻害または誘導する薬剤を併用しても、臨床的に重大な薬物相互作用の証拠は観察されなかった[19]。

ビカルタミドは比較的高濃度で循環し、かつ蛋白質との結合性が高いため、ワルファリン、フェニトイン、テオフィリン、アスピリンなどの蛋白質との結合性が高い薬剤が血漿中の結合蛋白質から追い出される可能性がある[108][109]。その結果、これらの薬剤の遊離濃度が上昇し、効果や副作用が増強され、投与量の調整が必要になる可能性がある[108]。特にビカルタミドは、ワルファリンなどのクマリン系抗凝固剤を血漿中の結合蛋白質(すなわちアルブミン)から追い出し、抗凝固作用が増強される可能性があることがin vitro で確認されており、このため、ビカルタミドをこれらの薬剤と併用する場合には、プロトロンビン時間を注意深く観察し、必要に応じて投与量を調整することが推奨されている。しかし、それにもかかわらず、約3,000人の患者を対象とした臨床試験において、ビカルタミドと他の薬剤との相互作用を示す決定的な証拠は発見されていない[109]。

薬理学的特性[編集]

薬理作用[編集]

抗アンドロゲン活性[編集]

ビカルタミドは、アンドロゲン性ホルモンであるテストステロンとDHTの主要な生物学的標的であるアンドロゲン受容体(AR)に対して高選択的競合的完全遮断薬(IC50 = 159 - 243 nM)として作用し、従って抗アンドロゲン作用を有する[22][110][111][112]。ビカルタミドの活性は、(R)-異性体にある[113]。ARに対する選択性のため、ビカルタミドは他のステロイドホルモン受容体と重要な相互作用を示さず、臨床的にはオフターゲットのホルモン活性(例:黄体ホルモン、エストロゲン、糖質コルチコイド、抗鉱質コルチコイド)はない[113][114][115][116]。しかし、ビカルタミドは、アンタゴニストであるプロゲステロン受容体(PR)に弱い親和性を示すことが報告されており、そのため、何らかの抗黄体ホルモン作用を有する可能性があるとされている[117]。ビカルタミドは、5α-リダクターゼを阻害せず、アンドロゲンのステロイド生成に関与する他の酵素(CYP17A1など)を阻害することも知られている[118]。ビカルタミドはエストロゲン受容体(ER)には結合しないが、男性に単剤で使用した場合、AR阻害により二次的にエストロゲン量を増加させる可能性があり、男性において間接的なエストロゲン作用を示す可能性がある[119]。ビカルタミドは、体内のアンドロゲン産生を抑制も阻害もしない(すなわち、抗ゴナドトロピンやアンドロゲンのステロイド産生阻害薬として作用したり、アンドロゲンレベルを低下させたりしない)ため、もっぱらARに拮抗することで抗アンドロゲン作用を発揮する[2][113][114]。古典的な核内ARに加えて、ビカルタミドは膜型アンドロゲン受容体(mAR)でも評価され、ZIP9の強力なアンタゴニスト(IC50 = 66.3 nM)として作用することが判明したが、GPRC6Aとは相互作用しないと思われた[120][121]。

ビカルタミドのARに対する親和性は、バイオアッセイにおいてテストステロンの2.5 - 10倍のARアゴニストであり、前立腺における主な内因性リガンドであるDHTの親和性の約30 - 100分の1と比較的低い値を示す[1][112][122][123]。しかし、ビカルタミドの一般的な臨床投与量では、テストステロンやDHTの数千倍の血中濃度となり、これらが受容体に結合して活性化するのを強力に阻止することができる[18][19][75][115][124][125][126][127][128]。これは、外科的または内科的な去勢を行った場合に特に顕著で、循環血液中のテストステロン濃度は約95%減少し、前立腺中のDHT濃度は約50 - 60%減少する[112][129]。女性の場合、テストステロン濃度は男性に比べて大幅に低い(20 - 40倍)ため[130]、より少量のビカルタミド(例えば、多毛症に対する臨床試験では25mg/日)が必要となる[11][46][131][132]。

下垂体および視床下部のARをビカルタミドで遮断すると、男性の場合、アンドロゲンの視床下部-下垂体-性腺軸(HPG軸)への負のフィードバックが阻止され、その結果、下垂体の黄体形成ホルモン(LH)の分泌が脱抑制される[85]。その結果、循環LHレベルが上昇し、性腺でのテストステロンの産生が活性化され、ひいてはエストラジオールの産生も活性化される[133]。150mg/日のビカルタミド単剤投与により、テストステロンは1.5 - 2倍(59 - 97%)、エストラジオールは1.5 - 2.5倍(65 - 146%)に増加することが確認されている[23][132][134]。テストステロンおよびエストラジオールに加えて、DHT、性ホルモン結合グロブリンおよびプロラクチンの濃度にも小さな増加が認められた[132]。エストラジオール濃度は閉経前女性の正常範囲下限と近い値を示しており、一方テストステロン濃度は一般的に男性の正常範囲の上限に位置している[114][134][135]。テストステロン濃度は、エストラジオール濃度の上昇によるHPG軸への負のフィードバックにより、通常、男性の正常範囲を超えることはない[85]。ビカルタミドがHPG軸に影響を与え、ホルモン濃度を上昇させるのは男性のみで、女性には影響しない[136][137][138]。これは、女性のアンドロゲン濃度が非常に低く、基礎的なHPG軸の抑制が行われないためである[136][137][138]。前立腺癌などのアンドロゲン依存性疾患の治療に有効であることからもわかるように、ビカルタミドの抗アンドロゲン作用は、結果として生じるテストステロンの増加に因る影響を大幅に上回る[80]。しかし、エストラジオールの増加はビカルタミドによって抑制されないため、女性化乳房や雌性化の原因となる[139]。ビカルタミドの単剤投与は、男性のゴナドトロピンおよび性ホルモンレベルを上昇させるが、ビカルタミドとGnRHアナログなどの抗ゴナドトロピン薬、エストロゲン、プロゲストーゲンを併用すると、HPG軸への負のフィードバックが維持されるため、この現象は起こらない[140][141][142]。

ビカルタミドを含むNSAA単剤療法は、外科的・内科的な去勢を伴うアンドロゲン遮断療法の方法とは、多くの忍容性の違いがある。例えば、GnRHアナログ製剤では、ほてり、抑うつ、疲労、性機能障害などの発現率がNSAA単剤療法に比べて非常に高いことが分かっている。これは、GnRHアナログ製剤が、アンドロゲンに加えてエストロゲンの産生も抑制し、エストロゲン欠乏症を引き起こすためと考えられている[143][144][145]。一方、NSAA単独療法では、エストロゲンレベルは減少せず、むしろ増加するため、エストロゲンが過剰に分泌され、アンドロゲンの欠乏を補い、気分、エネルギー、性機能の維持が可能となる[143][144][145]。また、3α-アンドロスタンジオールや3β-アンドロスタンジオールのようなテストステロンから生成される神経ステロイドは、ERβアゴニストであり、前者は強力なGABAA受容体陽性アロステリック調節因子であるため、関与している可能性がある[146][147][148][149][150][151][152]。性機能障害の具体的なケースでは、アンドロゲン産生抑制薬を併用しなければ、脳内のビカルタミドによるARの遮断が不完全であり、性的機能に顕著な影響を与えるには不十分であることが、この違いの追加的な可能性として考えられる[要出典]。

通常の環境下では、ビカルタミドはARを活性化する能力を持たない[153][154]。しかし、前立腺癌では、ARの変異や過剰発現が前立腺細胞に蓄積し、ビカルタミドがARのアンタゴニストからアゴニストへと変わることがある[153][155]。この結果、ビカルタミドが前立腺癌の成長を逆説的に促進することになり、抗アンドロゲン剤を中止すると前立腺癌の成長速度が逆説的に遅くなる抗アンドロゲン薬離脱症候群という現象の原因となっている[153][155]。

ビカルタミドの単剤投与は、精巣の精子形成、精巣の微細構造、および男性の生殖能力の一部にほとんど影響を及ぼさないようである[76][156][157]。これは、精巣(男性のテストステロンの約95%が産生される場所)のテストステロン濃度が非常に高く(血中濃度の200倍)、精子形成を維持するために実際に必要な精巣のテストステロン濃度は正常値の極一部(10%未満)に過ぎないためと考えられる[158][159][160]。そのため、ビカルタミドは、この精巣でテストステロンと競合し、アンドロゲンのシグナル伝達や機能を阻害することはできないと考えられる[158][159][160]。しかし、ビカルタミドは精巣の精子形成には影響を与えないとおぼしき一方で、精巣以外の精巣上体や精管でのAR依存性の精子の成熟や輸送を阻害する可能性があり、その結果、男性の生殖能力に障害を与える可能性がある[161]。さらに、エストロゲン、プロゲストーゲン、GnRHアナログなどの他の薬剤とビカルタミドを併用すると、それぞれの薬剤が男性の生殖能力に悪影響を及ぼすため、精子形成が損なわれる可能性がある[162][163][164][165][166][167]。これらの薬剤は性腺のアンドロゲン産生を強く抑制することができ、精巣の精子形成を著しく損なったり、消失させたりする可能性がある。また、エストロゲンは、十分に高い濃度で精巣に直接的かつ長期的な細胞毒性を及ぼす可能性がある[162][163][164][165][166][167]。

その他の活性[編集]

ビカルタミドは、前臨床研究において、CYP3A4、CYP2C9、CYP2C19、CYP2D6を含む特定のシトクロムP450酵素の阻害薬または誘導薬として作用することが確認されているが、最大150mg/日の投与を受けたヒトにおいては、その証拠は見いだされなかった[1]。また、in vitro では、CYP27A1(コレステロール27水酸化酵素)の強力な阻害剤として、また、CYP46A1(コレステロール24水酸化酵素)の阻害剤として同定されているが、in vivo またはヒトでの評価・確認はまだ行われておらず、臨床的意義は不明である[168][169]。ビカルタミドは、P-糖蛋白質(ABCB1)阻害剤であることが判明している[170][171][172]。他の第一世代のNSAAやエンザルタミドと同様に、in vitro でGABAA受容体を介した電気信号に対して弱い非競合的阻害剤として作用することが確認されている(IC50=5.2μM)[173][174]。しかし、エンザルタミドとは異なり、ビカルタミドには痙攣などの中枢性の副作用は認められておらず、この知見の臨床的意義は不明である[173][174]。

薬物動態[編集]

ヒトにおける絶対的なバイオアベイラビリティーは不明であるが、ビカルタミドは広範かつ良好に吸収されることが知られている[1][2]。その吸収は食事の影響を受けない[2][175]。ビカルタミドの吸収は、150mg/日までは直線的で、それ以上の用量では飽和状態となり、300mg/日以上の用量ではビカルタミド濃度は定常状態でそれ以上上昇しない[1][19][176][177]。(R)-ビカルタミドの吸収は遅く、投与後31 - 39時間でピークに達するのに対し、(S)-ビカルタミドは吸収が非常に速い[1][18][19]。投与量に関係なく、4 - 12週間の投与で定常濃度に達し、(R)-ビカルタミドの濃度は10 - 20倍に増加する[19][127][178][179]。定常濃度に達するまでの期間が長いのは、ビカルタミドの排泄半減期が非常に長いことに起因する[127]。

ビカルタミドの組織分布は十分に明らかにされていない[180]。性交時にパートナーの女性に移行する可能性のある精液中のビカルタミドの量は少なく、重要ではないと考えられている[75]。ラットやイヌを用いた動物実験では、ビカルタミドは血液脳関門を通過しないため、脳には入らないと考えられていたので[115][181][182][183]、当初は末梢選択的な抗アンドロゲン剤だと考えられていた[115][181]。しかし、その後の臨床試験で、ヒトではそうではないことが判明し、種の違いが示された。ビカルタミドはヒトの脳内に入り、それに伴い中枢性抗アンドロゲン作用に合致した効果と副作用を発揮する[1][85][184][185][186]。ビカルタミドは血漿蛋白質との結合率が高く(ラセミ体で96.1%、(R)-ビカルタミドで99.6%)、主にアルブミンと結合し、性ホルモン結合グロブリンや糖質ステロイド結合グロブリンとの結合は極僅かである[1][3][118][180]。

ビカルタミドは肝臓で代謝される[3][175]。(R)-ビカルタミドは、CYP3A4による水酸化を介してゆっくりと、ほぼ独占的に代謝され、(R)-ヒドロキシビカルタミドになる[1][3][175][187]。この代謝物は、UGT1A9によってグルクロン酸抱合体に変換される[1][6][175][188]。(R)-ビカルタミドとは対照的に、(S)-ビカルタミドは速やかに、主にグルクロン酸抱合で代謝される(水酸化は行われない)[175]。ビカルタミドの代謝物はいずれも活性がないことが知られており、血漿中では代謝物のレベルは低く、未変化のビカルタミドが優勢である[1][3][5]。ビカルタミドは立体選択的に代謝されるため、(R)-ビカルタミドは (S)-ビカルタミドに比べて最終的な半減期が非常に長く、その濃度は単回投与で約10 - 20倍、定常状態では約100倍になる[19][187][189]。(R)-ビカルタミドの排泄半減期は、単回投与で5.8日、反復投与で7 - 10日と比較的長い[190]。

ビカルタミドは糞中(43%)と尿中(34%)に概ね同程度の割合で排泄され、代謝物も尿中と胆汁中にほぼ均等に排泄される[3][175][191][192]。ビカルタミドはかなりの部分が未代謝の状態で排泄され、未変化体と代謝物のグルクロン酸抱合体も排泄される[113]。ビカルタミドとその代謝物のグルクロニド抱合体は、非抱合体のビカルタミドとは異なり、速やかに循環系から排除される[1][175][193]。

ビカルタミドの薬物動態は、食物の摂取、年齢や体重、腎機能障害、軽度から中等度の肝機能障害の影響を受けない[1][127]。しかし、日本人では白人に比べてビカルタミドの定常濃度が高い[1]。

化学的特徴[編集]

ビカルタミドは,エナンチオマーである (R)-ビカルタミド(右旋性)と (S)-ビカルタミド(左旋性)からなるラセミ混合物である[18]。

ビカルタミドはフルタミドから派生した合成の非ステロイド性化合物である[194]。ビシクロ化合物(2つの環を持つ)であり、アニリド(N-フェニルアミド)またはアニリン、ジアリルプロピオンアミド、トルイジン類に分類され、さまざまに言及されている[194][195]。

臨床試験[編集]

ビカルタミドは1987年に最初の第I相臨床試験が行われ[109]、前立腺癌における最初の第II相臨床試験の結果が1990年に発表された[196]。ICIの製薬部門は1993年にゼネカという独立した会社に分割され、1995年4月と5月にゼネカ(現在のアストラゼネカ、1999年にアストラABと合併後)が前立腺癌の治療のためにビカルタミドの米国での承認前マーケティングを開始した[197]。1995年5月に英国で発売され[198]、続いて1995年10月4日に米国FDAより、GnRHアナログと併用して50mg/日の用量で前立腺癌の治療薬として承認された[199][200]。

GnRHアナログとの併用療法が導入された後、ビカルタミドは、前立腺癌の治療のために150mg/日の用量で単剤療法として開発され、1990年代後半から2000年代前半にかけて、ヨーロッパ、カナダおよびその他の多くの国でこの適応症で承認された[19][201][202][203]。ビカルタミドのこの用途は、2002年に米国でもFDAによって審査されたが[204]、最終的には承認されなかった[80]。日本では、前立腺癌の治療薬として、ビカルタミドを80mg/日の用量で単独またはGnRHアナログと併用することが許可されている[39]。日本で使用されているビカルタミドの独自の80mgの用量は、日本人男性におけるビカルタミドの薬物動態の違いが観察されたことに基づいて、日本での開発のために選択された[40]。

早期前立腺癌の試験において、非転移性前立腺癌に対するビカルタミド単剤療法が否定的な結果となったことを受け、英国(2003年10月または11月)[205]、その他の欧州諸国およびカナダ(2003年8月)を含む多くの国で、非転移性前立腺癌治療に特化したビカルタミドの承認が取り消された[19][206][207][208]。また、米国およびカナダでは、本適応症に対する150mg/日のビカルタミドの使用を明確に推奨していた[209]。一方で、ビカルタミドは局所進行前立腺癌および転移性前立腺癌の治療に有効であり、引き続き承認され、使用されている[19]。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v “Bicalutamide: clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 43 (13): 855–878. (2004). doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00003. PMID 15509184. "These data indicate that direct glucuronidation is the main metabolic pathway for the rapidly cleared (S)-bicalutamide, whereas hydroxylation followed by glucuronidation is a major metabolic pathway for the slowly cleared (R)-bicalutamide."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 497, 521. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. オリジナルの11 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 121, 1288, 1290. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. オリジナルの8 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Enantiomer selective glucuronidation of the non-steroidal pure anti-androgen bicalutamide by human liver and kidney: role of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A9 enzyme”. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 113 (2): 92–102. (August 2013). doi:10.1111/bcpt.12071. PMC 3815647. PMID 23527766.

- ^ a b “Nilutamide: an antiandrogen for the treatment of prostate cancer”. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 31 (1): 65–75. (1997). doi:10.1177/106002809703100112. PMID 8997470. "page 67: Currently, information is not available regarding the activity of the major urinary metabolites of bicalutamide, bicalutamide glucuronide, and hydroxybicalutamide glucuronide."

- ^ a b “An evaluation of bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer”. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 3 (9): 1313–28. (September 2002). doi:10.1517/14656566.3.9.1313. PMID 12186624. "The clearance of bicalutamide occurs pre- dominantly by hepatic metabolism and glucuronidation, with excretion of the resulting inactive metabolites in the urine and faces."

- ^ a b Skidmore-Roth, Linda (16 July 2015). Mosby's Drug Guide for Nursing Students, with 2016 Update. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-323-17297-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “Bicalutamide”. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2016年12月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年12月8日閲覧。

- ^ Wass, John A.H.; Stewart, Paul M. (28 July 2011). Oxford Textbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes. OUP Oxford. pp. 1625–. ISBN 978-0-19-923529-2. オリジナルの11 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Shergill, Iqbal; Arya, Manit; Grange, Philippe R.; Mundy, A. R. (2010) (英語). Medical Therapy in Urology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 40. ISBN 9781848827042. オリジナルの28 October 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c Williams, Hywel; Bigby, Michael; Diepgen, Thomas; Herxheimer, Andrew; Naldi, Luigi; Rzany, Berthold (22 January 2009). Evidence-Based Dermatology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 529–. ISBN 978-1-4443-0017-8. オリジナルの2 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b “Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy for Transgender Females”. Clin Obstet Gynecol 61 (4): 705–721. (December 2018). doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396. PMID 30256230.

- ^ a b Jameson, J. Larry; De Groot, Leslie J. (25 February 2015). Edndocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2425–2426, 2139. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2

- ^ a b “Insights of priapism mechanism and rationale treatment for recurrent priapism”. Asian Journal of Andrology 10 (1): 88–101. (2008). doi:10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00314.x. PMID 18087648.

- ^ “Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life”. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 7 (9): 2996–3010. (2010). doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01902.x. PMID 20626600.

- ^ Shapiro, Jerry (12 November 2012). Hair Disorders: Current Concepts in Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, An Issue of Dermatologic Clinics. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-1-4557-7169-1

- ^ a b c d e “カソデックス錠80mg/カソデックスOD錠80mg 添付文書”. www.info.pmda.go.jp. PMDA. 2021年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k “Casodex- bicalutamide tablet”. DailyMed (2019年9月1日). 2020年5月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l “Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer”. Drugs 66 (6): 837–50. (2006). doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007. PMID 16706554. オリジナルの28 August 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 2016年8月13日閲覧。.

- ^ “Drug-induced photosensitivity to bicalutamide – case report and review of the literature”. Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine 32 (3): 161–4. (May 2016). doi:10.1111/phpp.12230. PMID 26663090.

- ^ “Drug-induced photosensitivity to bicalutamide – case report and review of the literature”. Reactions Weekly 1612 (1): 37. (2016). doi:10.1007/s40278-016-19790-1.

- ^ a b “Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships”. Current Medicinal Chemistry 7 (2): 211–47. (February 2000). doi:10.2174/0929867003375371. PMID 10637363.

- ^ a b Strauss III, Jerome F.; Barbieri, Robert L. (28 August 2013). Yen & Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 688–. ISBN 978-1-4557-5972-9. "Bone density improves in men receiving bicalutamide, most likely secondary to the 146% increase in estradiol and the fact that estradiol is the major mediator of bone density in men."

- ^ Marcus, Robert; Feldman, David; Nelson, Dorothy; Rosen, Clifford J. (8 November 2007). Osteoporosis. Academic Press. pp. 1354–. ISBN 978-0-08-055347-4. オリジナルの11 June 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antiandrogens and their efficacy in prostate cancer”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 34 (5): 405–17. (May 1998). doi:10.2165/00003088-199834050-00005. PMID 9592622.

- ^ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006) (英語). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 515. ISBN 9783527607495

- ^ “カソデックス錠80mg/カソデックスOD錠80mg インタビューフォーム”. PMDA. 2021年6月3日閲覧。

- ^ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2019). WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- ^ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 381. ISBN 9781284057560

- ^ “Bicalutamide”. International Drug Price Indicator Guide. 2016年12月8日閲覧。

- ^ “NADAC as of 2016-12-07 | Data.Medicaid.gov”. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2016年12月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年1月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Bicalutamide – International Drug Names”. Drugs.com. 2016年9月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年8月13日閲覧。

- ^ “[A new anti-androgen, bicalutamide (Casodex), for the treatment of prostate cancer—basic clinical aspects]” (Japanese). Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer & Chemotherapy 26 (8): 1201–7. (1999). PMID 10431591.

- ^ “1999 Annual Report and Form 20-F”. AstraZeneca. 2017年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ “MDV3100 for the treatment of prostate cancer”. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 21 (2): 227–33. (February 2012). doi:10.1517/13543784.2012.651125. PMID 22229405.

- ^ Pchejetski, Dmitri; Alshaker, Heba; Stebbing, Justin (2014). “Castrate-resistant prostate cancer: the future of antiandrogens”. Trends in Urology & Men's Health 5 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1002/tre.371.

- ^ Campbell (2014年1月22日). “Slowing Sales for Johnson & Johnson's Zytiga May Be Good News for Medivation”. The Motley Fool. 2016年8月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年7月20日閲覧。 “[...] the most commonly prescribed treatment for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer: bicalutamide. That was sold as AstraZeneca's billion-dollar-a-year drug Casodex before losing patent protection in 2008. AstraZeneca still generates a few hundred million dollars in sales from Casodex, [...]”

- ^ Chang, Stephen (10 March 2010), Bicalutamide BPCA Drug Use Review in the Pediatric Population, U.S. Department of Health and Human Service, オリジナルの24 October 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Current topics and perspectives relating to hormone therapy for prostate cancer”. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 13 (5): 401–10. (October 2008). doi:10.1007/s10147-008-0830-y. PMID 18946750.

- ^ a b “Bicalutamide 80 mg combined with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (LHRH-A) versus LHRH-A monotherapy in advanced prostate cancer: findings from a phase III randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial in Japanese patients”. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 10 (2): 194–201. (2007). doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500934. PMID 17199134. "In most countries, bicalutamide is given at a dose of 50 mg when used in combination with an LHRH-A. However, based on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, the approved dose of bicalutamide in Japanese men is 80 mg per day."

- ^ Bagatelle, Carrie; Bremner, William J. (27 May 2003). Androgens in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-59259-388-0

- ^ “Combined androgen blockade: the case for bicalutamide”. Clinical Prostate Cancer 3 (4): 215–9. (March 2005). doi:10.3816/cgc.2005.n.002. PMID 15882477.

- ^ “Clinical benefits of bicalutamide compared with flutamide in combined androgen blockade for patients with advanced prostatic carcinoma: final report of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter trial. Casodex Combination Study Group”. Urology 50 (3): 330–6. (September 1997). doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00279-3. PMID 9301693.

- ^ Shlomo Melmed (1 January 2016). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 752–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7

- ^ “Bicalutamide vs cyproterone acetate in preventing flare with LHRH analogue therapy for prostate cancer—a pilot study”. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 8 (1): 91–4. (2005). doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500784. PMID 15711607.

- ^ a b c “Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment”. Acta Clinica Belgica 68 (4): 268–74. (2013). doi:10.2143/ACB.3267. PMID 24455796.

- ^ “Acne in the adult”. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 9 (1): 1–10. (January 2009). doi:10.2174/138955709787001730. PMID 19149656.

- ^ “Etiopathogenesis and Therapeutic Approach to Adult Onset Acne”. Indian Journal of Dermatology 61 (4): 403–7. (2016). doi:10.4103/0019-5154.185703. PMC 4966398. PMID 27512185.

- ^ Lotti, Francesco; Maggi, Mario (2015). “Hormonal Treatment for Skin Androgen-Related Disorders”. European Handbook of Dermatological Treatments: 1451–1464. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-45139-7_142. ISBN 978-3-662-45138-0.

- ^ Müderris, II; Öner, G (2009). “Hirsutizm Tedavisinde Flutamid ve Bikalutamid Kullanımı [Flutamide and Bicalutamide Treatment in Hirsutism]” (トルコ語). Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Endocrinology-Special Topics 2 (2): 110–2. ISSN 1304-0529.

- ^ “Combined Oral Contraception and Bicalutamide in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Severe Hirsutism: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial”. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103 (3): 824–838. (March 2018). doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01186. PMID 29211888.

- ^ Fishman, Sarah L.; Paliou, Maria; Poretsky, Leonid; Hembree, Wylie C. (2019). “Endocrine Care of Transgender Adults”. Transgender Medicine. Contemporary Endocrinology. pp. 143–163. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05683-4_8. ISBN 978-3-030-05682-7. ISSN 2523-3785

- ^ “Bicalutamide as an Androgen Blocker With Secondary Effect of Promoting Feminization in Male-to-Female Transgender Adolescents”. J Adolesc Health 64 (4): 544–546. (April 2019). doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.296. PMC 6431559. PMID 30612811.

- ^ Gooren, LJ (31 March 2011). “Clinical practice. Care of transsexual persons.”. The New England Journal of Medicine 364 (13): 1251–7. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1008161. PMID 21449788.

- ^ Deutsch, Madeline (17 June 2016), Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People (2nd ed.), University of California, San Francisco: Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, p. 28

- ^ Benjamin Vincent (21 June 2018). Transgender Health: A Practitioner's Guide to Binary and Non-Binary Trans Patient Care. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-1-78450-475-5

- ^ “Clinical review: Breast development in trans women receiving cross-sex hormones”. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 11 (5): 1240–7. (May 2014). doi:10.1111/jsm.12487. PMID 24618412.

- ^ Schoelwer, Melissa; Eugster, Erica A. (2015). “Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty”. Puberty from Bench to Clinic. Endocrine Development. 29. pp. 230–239. doi:10.1159/000438895. ISBN 978-3-318-02788-4. ISSN 1421-7082. PMC 5345994. PMID 26680582

- ^ Haddad, Nadine G.; Eugster, Erica A. (2019). “Peripheral precocious puberty including congenital adrenal hyperplasia: causes, consequences, management and outcomes”. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 33 (3): 101273. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2019.04.007. hdl:1805/19111. ISSN 1521-690X. PMID 31027974.

- ^ Haddad, Nadine G.; Eugster, Erica A. (2012). “Peripheral Precocious Puberty: Interventions to Improve Growth”. Handbook of Growth and Growth Monitoring in Health and Disease. pp. 1199–1212. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1795-9_71. ISBN 978-1-4419-1794-2

- ^ Zacharin, Margaret (2019). “Disorders of Puberty: Pharmacotherapeutic Strategies for Management”. Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 261. pp. 507–538. doi:10.1007/164_2019_208. ISBN 978-3-030-50493-9. ISSN 0171-2004. PMID 31144045

- ^ Kliegman, Robert M.; Stanton, Bonita; St. Geme, Joseph; Schor, Nina F (17 April 2015). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2661–. ISBN 978-0-323-26352-8

- ^ “Bicalutamide plus anastrozole for the treatment of gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty in boys with testotoxicosis: a phase II, open-label pilot study (BATT)”. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism 23 (10): 999–1009. (October 2010). doi:10.1515/jpem.2010.161. PMID 21158211.

- ^ “Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature”. Asian Journal of Andrology 14 (1): 156–63. (2012). doi:10.1038/aja.2011.114. PMC 3753435. PMID 22057380.

- ^ “Priapism: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management”. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 7 (1 Pt 2): 476–500. (2010). doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01625.x. PMID 20092449.

- ^ “The pharmacological management of intermittent priapismic states”. BJU International 102 (11): 1515–21. (2008). doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07951.x. PMID 18793304.

- ^ “Antiandrogens in the treatment of priapism”. Urology 59 (1): 138. (2002). doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01492-3. PMID 11796309.

- ^ a b Skidmore-Roth, Linda (17 April 2013). Mosby's 2014 Nursing Drug Reference – Elsevieron VitalSource. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-323-22267-9

- ^ “Clinical review: Ethical and medical considerations of androgen deprivation treatment of sex offenders”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96 (12): 3628–37. (2011). doi:10.1210/jc.2011-1540. PMID 21956411.

- ^ “Potential side effects of androgen deprivation treatment in sex offenders”. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 37 (1): 53–8. (2009). PMID 19297634.

- ^ “The efficacy, safety and ethics of the use of testosterone-suppressing agents in the management of sex offending”. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity 23 (3): 271–8. (2016). doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000257. PMID 27032060.

- ^ Dangerous Sex Offenders: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Pub. (1999). pp. 111–. ISBN 978-0-89042-280-9

- ^ “Androgen deprivation treatment of sexual behavior”. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine 31: 149–63. (2011). doi:10.1159/000330196. ISBN 978-3-8055-9825-5. PMID 22005210.

- ^ “Effect of combined androgen blockade with an LHRH agonist and flutamide in one severe case of male exhibitionism”. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 35 (4): 338–41. (1990). doi:10.1177/070674379003500412. PMID 2189544.

- ^ a b c “COSUDEX® (bicalutamide) 150 mg tablets”. TGA. 2016年9月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b “An overview of animal toxicology studies with bicalutamide (ICI 176,334)”. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences 22 (2): 75–88. (May 1997). doi:10.2131/jts.22.2_75. PMID 9198005.

- ^ Smith, Robert E. (4 April 2013). Medicinal Chemistry – Fusion of Traditional and Western Medicine. Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 306–. ISBN 978-1-60805-149-6. オリジナルの29 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Mosby's GenRx: A Comprehensive Reference for Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs. Mosby. (2001). pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-323-00629-3

- ^ PDR, Thomson (2004). Physicians' Desk Reference. Thomson PDR. ISBN 978-1-56363-471-0

- ^ a b c Chabner, Bruce A.; Longo, Dan L. (8 November 2010). Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 679–680. ISBN 978-1-60547-431-1

- ^ J. Ramon; L.J. Denis (5 June 2007). Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-3-540-40901-4

- ^ a b c d e f “The role of antiandrogen monotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer”. BJU Int. 91 (5): 455–61. (March 2003). doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04026.x. PMID 12603397.

- ^ Lutz Moser (1 January 2008). Controversies in the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-3-8055-8524-8

- ^ Prostate Cancer. Demos Medical Publishing. (20 December 2011). pp. 504–505. ISBN 978-1-935281-91-7

- ^ a b c d “Nonsteroidal antiandrogens: a therapeutic option for patients with advanced prostate cancer who wish to retain sexual interest and function”. BJU International 87 (1): 47–56. (January 2001). doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00988.x. PMID 11121992.

- ^ a b c d e “Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer”. Drugs 66 (6): 837–50. (2006). doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007. PMID 16706554.

- ^ a b c d Jeffrey K. Aronson (21 February 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 149–150, 253–258. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7

- ^ James Barrett (2007). Transsexual and Other Disorders of Gender Identity: A Practical Guide to Management. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-1-85775-719-4

- ^ “Nutritional factors and hair loss”. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 27 (5): 396–404. (2002). doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01076.x. PMID 12190640.

- ^ “Hormone therapy of prostate cancer: is there a role for antiandrogen monotherapy?”. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 35 (2): 121–32. (2000). doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00051-2. PMID 10936469.

- ^ “Hepatotoxicity induced by antiandrogens: a review of the literature”. Urol. Int. 73 (4): 289–95. (2004). doi:10.1159/000081585. PMID 15604569.

- ^ “Bicalutamide-associated fulminant hepatotoxicity”. Pharmacotherapy 28 (8): 1071–5. (2008). doi:10.1592/phco.28.8.1071. PMID 18657023.

- ^ JORDAN V. CRAIG; B.J.A. Furr (5 February 2010). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 356–. ISBN 978-1-59259-152-7

- ^ “Pneumonitis associated with nonsteroidal antiandrogens: presumptive evidence of a class effect”. Annals of Internal Medicine 137 (7): 625. (October 2002). doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00029. PMID 12353966. "An estimated 0.77% of the 6,480 nilutamide-treated patients, 0.04% of the 41,700 flutamide-treated patients, and 0.01% of the 86,800 bicalutamide-treated patients developed pneumonitis during the study period."

- ^ “Drug safety is a barrier to the discovery and development of new androgen receptor antagonists”. Prostate 71 (5): 480–8. (2011). doi:10.1002/pros.21263. PMID 20878947.

- ^ “Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy”. N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (5): 424–33. (2014). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1405095. PMC 4418931. PMID 24881730.

- ^ “Enzalutamide: a review of its use in chemotherapy-naïve metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer”. Drugs Aging 32 (3): 243–9. (2015). doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0248-y. PMID 25711765.

- ^ “Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy”. N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (18): 1755–6. (2014). doi:10.1056/NEJMc1410239. hdl:2318/150443. PMID 25354111.

- ^ “The preclinical development of bicalutamide: pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action”. Urology 47 (1A Suppl): 13–25; discussion 29–32. (1996). doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80003-3. PMID 8560673.

- ^ “Bicalutamide and third-generation aromatase inhibitors in testotoxicosis”. Pediatrics 126 (3): e728-33. (September 2010). doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0596. PMC 4096839. PMID 20713483.

- ^ “Adverse reactions to spironolactone. A report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program”. JAMA 225 (1): 40–3. (July 1973). doi:10.1001/jama.1973.03220280028007. PMID 4740303.

- ^ Munoz, Ricardo; da Cruz, Eduardo; Vetterly, Carol G. et al. (26 June 2014). Handbook of Pediatric Cardiovascular Drugs. Springer. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-1-4471-2464-1

- ^ “Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and insulin resistance in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, and effect of bicalutamide on hirsutism, CRP levels and insulin resistance”. Hormone Research 62 (6): 283–7. (2004). doi:10.1159/000081973. PMID 15542929.

- ^ a b Nurse Practitioner's Drug Handbook. Springhouse Corp.. (2000). ISBN 9780874349979

- ^ a b “Tolerability, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of bicalutamide 300 mg, 450 mg or 600 mg as monotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer, compared with castration”. BJU International 98 (3): 563–72. (September 2006). doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06275.x. PMID 16771791.

- ^ Henry Winter Griffith (2008). Complete Guide to Prescription & Nonprescription Drugs 2009. HP Books. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-399-53463-8. "Overdose unlikely to threaten life [with NSAAs]."

- ^ Genrx (1999). 1999 Mosby's GenRx. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-00625-5. "A 79-year-old man attempted suicide by ingesting 13g of nilutamide (i.e., 43 times the maximum recommended dose). Despite immediate gastric lavage and oral administration of activated charcoal, plasma nilutamide levels peaked at 6 times the normal range 2 hours after ingestion. There were no clinical signs or symptoms or changes in parameters such as transaminases or chest x-ray. Maintenance treatment (150 mg/day) was resumed 30 days later."

- ^ a b “Antiandrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer”. European Urology 51 (2): 306–13; discussion 314. (February 2007). doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.043. PMID 17007995.

- ^ a b c “Worldwide activity and safety of bicalutamide: a summary review”. Urology 47 (1A Suppl): 70–9; discussion 80–4. (January 1996). doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(96)80012-4. PMID 8560681.

- ^ Balaj, K.C. (25 April 2016). Managing Metastatic Prostate Cancer In Your Urological Oncology Practice. Springer. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-3-319-31341-2. オリジナルの8 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Bicalutamide functions as an androgen receptor antagonist by assembly of a transcriptionally inactive receptor”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (29): 26321–6. (July 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M203310200. PMID 12015321.

- ^ a b c Denis, Louis (6 December 2012). Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer: A Key to Tailored Endocrine Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 128, 158, 203. ISBN 978-3-642-45745-6

- ^ a b c d Schellens, Jan H. M.; McLeod, Howard L.; Newell, David R. (5 May 2005). Cancer Clinical Pharmacology. OUP Oxford. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-19-262966-1. オリジナルの10 June 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c Becker, Kenneth L. (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1119, 1196, 1208. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2. オリジナルの8 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c d “The preclinical development of bicalutamide: pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action”. Urology 47 (1A Suppl): 13–25; discussion 29–32. (January 1996). doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80003-3. PMID 8560673.

- ^ Bagatelle, Carrie; Bremner, William J. (27 May 2003). Androgens in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-59259-388-0

- ^ “Enzalutamide and blocking androgen receptor in advanced prostate cancer: lessons learnt from the history of drug development of antiandrogens”. Res Rep Urol 10: 23–32. (2018). doi:10.2147/RRU.S157116. PMC 5818862. PMID 29497605.

- ^ a b “Casodex: preclinical studies and controversies”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 761 (1): 79–96. (June 1995). Bibcode: 1995NYASA.761...79F. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb31371.x. PMID 7625752.

- ^ “Estrogenic side effects of androgen deprivation therapy”. Reviews in Urology 9 (4): 163–80. (2007). PMC 2213888. PMID 18231613.

- ^ “Testosterone/bicalutamide antagonism at the predicted extracellular androgen binding site of ZIP9”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1864 (12): 2402–2414. (2017). doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.09.012. PMID 28943399.

- ^ “GPRC6A mediates the non-genomic effects of steroids”. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (51): 39953–64. (2010). doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.158063. PMC 3000977. PMID 20947496.

- ^ “Research on reproductive medicine in the pharmaceutical industry”. Human Fertility 1 (1): 56–63. (2009). doi:10.1080/1464727982000198131. PMID 11844311.

- ^ “Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer”. Science 324 (5928): 787–90. (2009). Bibcode: 2009Sci...324..787T. doi:10.1126/science.1168175. PMC 2981508. PMID 19359544. "[...] bicalutamide has relatively low affinity for AR (at least 30-fold reduced relative to the natural ligand dihydrotestosterone (DHT)) (7), [...]"

- ^ Furr, B J A (1997). “Relative potencies of flutamide and 'Casodex'”. Endocrine-Related Cancer 4 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1677/erc.0.0040197. ISSN 1351-0088.

- ^ Figg, William; Chau, Cindy H.; Small, Eric J. (14 September 2010). Drug Management of Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 56, 71–72, 75, 93. ISBN 978-1-60327-829-4

- ^ “The development of Casodex (bicalutamide): preclinical studies”. European Urology 29 Suppl 2: 83–95. (1996). doi:10.1159/000473846. PMID 8717469.

- ^ a b c d “Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of bicalutamide: defining an active dosing regimen”. Urology 47 (1A Suppl): 26–8; discussion 29–32. (January 1996). doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80004-5. PMID 8560674.

- ^ “Exploratory study of drug plasma levels during bicalutamide 150 mg therapy co-administered with tamoxifen or anastrozole for prophylaxis of gynecomastia and breast pain in men with prostate cancer”. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 56 (4): 415–20. (2005). doi:10.1007/s00280-005-1016-1. PMID 15838655.

- ^ “Daily dosing with flutamide or Casodex exerts maximal antiandrogenic activity”. Urology 50 (6): 913–9. (December 1997). doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00393-2. PMID 9426723.

- ^ Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. (30 November 2015). pp. 704–708, 711, 1104. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7

- ^ Moretti CG, Guccione L, Di Giacinto P, Cannuccia A, Meleca C, Lanzolla G, Andreadi A, Lauro D (April 2016). Efficacy and Safety of Myo-Inositol Supplementation in the Treatment of Obese Hirsute PCOS Women: Comparative Evaluation with OCP+Bicalutamide Therapy. ENDO 2016. Boston, Massachusetts.

- ^ a b c “Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antiandrogens and their efficacy in prostate cancer”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 34 (5): 405–17. (May 1998). doi:10.2165/00003088-199834050-00005. PMID 9592622.

- ^ “Effects on the endocrine system of long-term treatment with the non-steroidal anti-androgen Casodex in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia”. British Journal of Urology 75 (3): 335–40. (March 1995). doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1995.tb07345.x. PMID 7537602.

- ^ a b Marcus, Robert; Feldman, David; Nelson, Dorothy; Rosen, Clifford J. (8 November 2007). Osteoporosis. Academic Press. pp. 1354–. ISBN 978-0-08-055347-4. オリジナルの11 June 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Wein, Alan J.; Kavoussi, Louis R.; Novick, Andrew C.; Partin, Alan W.; Peters, Craig A. (25 August 2011). Campbell-Walsh Urology: Expert Consult Premium Edition: Enhanced Online Features and Print, 4-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2938–2939, 2946. ISBN 978-1-4160-6911-9. オリジナルの5 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b Diamanti-Kandarakis, Evanthia; Nestler, John E.; Pandas, Dimities; Pasquale, Renato (21 December 2009). Insulin Resistance and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Pathogenesis, Evaluation, and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-1-59745-310-3. オリジナルの19 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b Carrell, Douglas T.; Peterson, C. Matthew (23 March 2010). Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 163–. ISBN 978-1-4419-1436-1. オリジナルの4 July 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b Bouchard, P.; Caraty, A. (15 November 1993). GnRH, GnRH Analogs, Gonadotropins and Gonadal Peptides. CRC Press. pp. 455–456. ISBN 978-0-203-09205-7. "[...] when male levels of androgens are achieved in plasma, their effects on gonadotropin secretion are similar in women and men. [...] administration of flutamide in a group of normally-cycling women produced a clinical improvement of acne and hirsutism without any significant hormonal change. [...] All these data emphasize that physiological levels of androgens have no action on the regulation of gonadotropins in normal women. [...] Androgens do not directly play a role in gonadotropin regulation [in women]."

- ^ “Treatment of bicalutamide-induced breast events”. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 7 (12): 1773–9. (December 2007). doi:10.1586/14737140.7.12.1773. PMID 18062751.

- ^ Shlomo Melmed (1 January 2016). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 752–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7. "GnRH analogues, both agonists and antagonists, severely suppress endogenous gonadotropin and testosterone production [...] Administration of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide, goserelin) produces an initial stimulation of gonadotropin and testosterone secretion (known as a "flare"), which is followed in 1 to 2 weeks by GnRH receptor downregulation and marked suppression of gonadotropins and testosterone to castration levels. [...] To prevent the potential complications associated with the testosterone flare, AR antagonists (e.g., bicalutamide) are usually coadministered with a GnRH agonist for men with metastatic prostate cancer.399"

- ^ “Reduction in undesired sexual hair growth with anandron in male-to-female transsexuals—experiences with a novel androgen receptor blocker”. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 14 (5): 361–3. (1989). doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb02585.x. PMID 2612040.

- ^ “Merits and considerations in the use of anti-androgen”. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 31 (4B): 731–7. (1988). doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90024-6. PMID 3143862.

- ^ a b “Role of estrogen in normal male function: clinical implications for patients with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy”. The Journal of Urology 185 (1): 17–23. (January 2011). doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.094. PMID 21074215.

- ^ a b “Preliminary study with bicalutamide in heterosexual and homosexual patients with prostate cancer: a possible implication of androgens in male homosexual arousal”. BJU International 108 (1): 110–5. (July 2011). doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09764.x. PMID 20955264.

- ^ a b “The effect of estrogen on the sexual interest of castrated males: Implications to prostate cancer patients on androgen-deprivation therapy”. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 87 (3): 224–38. (September 2013). doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.01.006. PMID 23484454.

- ^ “Emerging roles for neurosteroids in sexual behavior and function”. Journal of Andrology 29 (5): 524–33. (2008). doi:10.2164/jandrol.108.005660. PMID 18567641.

- ^ “Mechanisms regulating male sexual behavior in the rat: role of 3 alpha- and 3 beta-androstanediols”. Biology of Reproduction 51 (3): 562–71. (September 1994). doi:10.1095/biolreprod51.3.562. PMID 7803627.

- ^ “The testosterone metabolite 3α-diol enhances female rat sexual motivation when infused in the nucleus accumbens shell”. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 7 (11): 3598–609. (November 2010). doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01937.x. PMC 4360968. PMID 20646182.

- ^ Chedrese, P. Jorge (13 June 2009). Reproductive Endocrinology: A Molecular Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 233–. ISBN 978-0-387-88186-7. オリジナルの5 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “3alpha-androstanediol, but not testosterone, attenuates age-related decrements in cognitive, anxiety, and depressive behavior of male rats”. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2: 15. (2010). doi:10.3389/fnagi.2010.00015. PMC 2874398. PMID 20552051.

- ^ “An estrogenic effect of 5alpha-androstane-3beta, 17beta-diol on the behavioral response to stress and on CRH regulation”. Neuropharmacology 54 (8): 1233–8. (June 2008). doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.03.016. PMID 18457850.

- ^ “Androgens with activity at estrogen receptor beta have anxiolytic and cognitive-enhancing effects in male rats and mice”. Hormones and Behavior 54 (5): 726–34. (November 2008). doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.07.013. PMC 3623974. PMID 18775724.

- ^ a b c “Enzalutamide: Development from bench to bedside”. Urologic Oncology 33 (6): 280–8. (June 2015). doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.12.017. PMID 25797385.

- ^ “Novel and next-generation androgen receptor-directed therapies for prostate cancer: Beyond abiraterone and enzalutamide”. Urologic Oncology 34 (8): 348–55. (August 2016). doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.025. PMID 26162486.

- ^ a b “Beyond abiraterone: new hormonal therapies for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer”. Cancer Biology & Therapy 15 (2): 149–55. (February 2014). doi:10.4161/cbt.26724. PMC 3928129. PMID 24100689.

- ^ Mulhall, John P. (21 February 2013). Fertility Preservation in Male Cancer Patients. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-139-61952-3. オリジナルの29 April 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Effects of long-term treatment with the anti-androgen bicalutamide on human testis: an ultrastructural and morphometric study”. Histopathology 38 (3): 195–201. (March 2001). doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01077.x. PMID 11260298.

- ^ a b Schill, Wolf-Bernhard; Comhaire, Frank H.; Hargreave, Timothy B. (26 August 2006). Andrology for the Clinician. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-3-540-33713-3. オリジナルの26 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b Nieschlag, Eberhard; Behre, Hermann M. (6 December 2012). Testosterone: Action – Deficiency – Substitution. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 130, 276. ISBN 978-3-642-72185-4

- ^ a b Cheng, C.Y. (24 October 2009). Molecular Mechanisms in Spermatogenesis. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 258–. ISBN 978-0-387-09597-4

- ^ Neumann, F.; Schenck, B. (1980). “Antiandrogens: Basic Concepts and Clinical Trials”. Regulation of Male Fertility. pp. 93–106. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8875-0_10. ISBN 978-94-009-8877-4

- ^ a b Johnson, Leonard R. (14 October 2003). Essential Medical Physiology. Academic Press. pp. 731–. ISBN 978-0-08-047270-6. オリジナルの15 February 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b Jones, C. A.; Reiter, L.; Greenblatt, E. (2016). “Fertility preservation in transgender patients”. International Journal of Transgenderism 17 (2): 76–82. doi:10.1080/15532739.2016.1153992. ISSN 1553-2739. "Traditionally, patients have been advised to cryopreserve sperm prior to starting cross-sex hormone therapy as there is a potential for a decline in sperm motility with high-dose estrogen therapy over time (Lubbert et al., 1992). However, this decline in fertility due to estrogen therapy is controversial due to limited studies."

- ^ a b Payne, Anita H.; Hardy, Matthew P. (28 October 2007). The Leydig Cell in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 422–431. ISBN 978-1-59745-453-7. "Estrogens are highly efficient inhibitors of the hypothalamic-hypophyseal-testicular axis (212–214). Aside from their negative feedback action at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary, direct inhibitory effects on the testis are likely (215,216). [...] The histology of the testes [with estrogen treatment] showed disorganization of the seminiferous tubules, vacuolization and absence of lumen, and compartmentalization of spermatogenesis."

- ^ a b Wakelin, Sarah H.; Maibach, Howard I.; Archer, Clive B. (1 June 2002). Systemic Drug Treatment in Dermatology: A Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-84076-013-2. オリジナルの25 July 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。. "[Cyproterone acetate] inhibits spermatogenesis and produces reversible infertility (but is not a male contraceptive)."

- ^ a b “The antiandrogen cyproterone acetate: discovery, chemistry, basic pharmacology, clinical use and tool in basic research”. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. 102 (1): 1–32. (1994). doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211261. PMID 8005205. "Spermatogenesis is also androgen-dependent and is inhibited by CPA, meaning that patients treated with high doses of CPA are sterile (Figure 23). All the effects of CPA are fully reversible."

- ^ a b Salam, Muhammad A. (2003). Principles & Practice of Urology: A Comprehensive Text. Universal-Publishers. pp. 684–. ISBN 978-1-58112-412-5. "Estrogens act primarily through negative feedback at the hypothalamic-pituitary level to reduce LH secretion and testicular androgen synthesis. [...] Interestingly, if the treatment with estrogens is discontinued after 3 yr. of uninterrupted exposure, serum testosterone may remain at castration levels for up to another 3 yr. This prolonged suppression is thought to result from a direct effect of estrogens on the Leydig cells."

- ^ “Marketed Drugs Can Inhibit Cytochrome P450 27A1, a Potential New Target for Breast Cancer Adjuvant Therapy”. Molecular Pharmacology 88 (3): 428–36. (September 2015). doi:10.1124/mol.115.099598. PMC 4551053. PMID 26082378.

- ^ “Binding of a cyano- and fluoro-containing drug bicalutamide to cytochrome P450 46A1: unusual features and spectral response”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 288 (7): 4613–24. (February 2013). doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.438754. PMC 3576067. PMID 23288837.

- ^ “Antiandrogens Inhibit ABCB1 Efflux and ATPase Activity and Reverse Docetaxel Resistance in Advanced Prostate Cancer”. Clinical Cancer Research 21 (18): 4133–42. (September 2015). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0269. PMC 4573793. PMID 25995342.

- ^ “Prostate cancer: Antiandrogens reverse docetaxel resistance via ABCB1 inhibition”. Nature Reviews. Urology 12 (7): 361. (July 2015). doi:10.1038/nrurol.2015.135. PMID 26057062.

- ^ “Drug resistance in castration resistant prostate cancer: resistance mechanisms and emerging treatment strategies”. American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Urology 3 (2): 64–76. (2015). PMC 4539108. PMID 26309896.

- ^ a b “Drug safety is a barrier to the discovery and development of new androgen receptor antagonists”. The Prostate 71 (5): 480–8. (April 2011). doi:10.1002/pros.21263. PMID 20878947.

- ^ a b Barrish, Joel; Carter, Percy; Cheng, Peter (2010). Accounts in Drug Discovery: Case Studies in Medicinal Chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-84973-126-3

- ^ a b c d e f g Weber, Georg F. (22 July 2015). Molecular Therapies of Cancer. Springer. pp. 318–. ISBN 978-3-319-13278-5. "Compared to flutamide and nilutamide, bicalutamide has a 2-fold increased affinity for the Androgen Receptor, a longer half-life, and substantially reduced toxicities. Based on a more favorable safety profile relative to flutamide, bicalutamide is indicated for use in combination therapy with a Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone analog for the treatment of advanced metastatic prostate carcinoma."

- ^ “Bicalutamide (Casodex) in the treatment of prostate cancer: history of clinical development”. The Prostate 34 (1): 61–72. (January 1998). doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19980101)34:1<61::AID-PROS8>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 9428389.

- ^ “Tolerability, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of bicalutamide 300 mg, 450 mg or 600 mg as monotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer, compared with castration”. BJU International 98 (3): 563–72. (September 2006). doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06275.x. PMID 16771791.

- ^ “Clinical progress with a new antiandrogen, Casodex (bicalutamide)”. Eur. Urol. 29 Suppl 2: 96–104. (1996). doi:10.1159/000473847. PMID 8717470.

- ^ DeVita Jr., Vincent T.; Lawrence, Theodore S.; Rosenberg, Steven A. (7 January 2015). DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. Wolters Kluwer Health. pp. 1142–. ISBN 978-1-4698-9455-3

- ^ a b Chu, Edward; DeVita Jr., Vincent T. (28 December 2012). Physicians' Cancer Chemotherapy Drug Manual 2013. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-284-04039-5

- ^ a b “Androgen receptor antagonists for prostate cancer therapy”. Endocrine-Related Cancer 21 (4): T105-18. (August 2014). doi:10.1530/ERC-13-0545. PMID 24639562.

- ^ “"Casodex" (ICI 176,334)--a new, pure, peripherally-selective anti-androgen: preclinical studies”. Hormone Research 32 Suppl 1 (1): 69–76. (1989). doi:10.1159/000181315. PMID 2533159.

- ^ “ICI 176,334: a novel non-steroidal, peripherally selective antiandrogen”. The Journal of Endocrinology 113 (3): R7-9. (June 1987). doi:10.1677/joe.0.113R007. PMID 3625091.

- ^ “Bicalutamide in the treatment of advanced prostatic carcinoma: a phase II noncomparative multicenter trial evaluating safety, efficacy and long-term endocrine effects of monotherapy”. The Journal of Urology 154 (6): 2110–4. (December 1995). doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66709-0. PMID 7500470.

- ^ “Expanding the therapeutic use of androgens via selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs)”. Drug Discovery Today 12 (5–6): 241–8. (March 2007). doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2007.01.003. PMC 2072879. PMID 17331889.

- ^ “What implications do the tolerability profiles of antiandrogens and other commonly used prostate cancer treatments have on patient care?”. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 132 Suppl 1: S27-35. (August 2006). doi:10.1007/s00432-006-0134-4. PMID 16896883.

- ^ a b Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1372–1373. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. オリジナルの3 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Enantiomer selective glucuronidation of the non-steroidal pure anti-androgen bicalutamide by human liver and kidney: role of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A9 enzyme”. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 113 (2): 92–102. (August 2013). doi:10.1111/bcpt.12071. PMC 3815647. PMID 23527766.

- ^ Butler, Sara K.; Govindan, Ramaswamy (25 October 2010). Essential Cancer Pharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-1-60913-704-5

- ^ Jordan, Virgil Craig; Furr, B. J. A. (5 February 2010). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 350–. ISBN 978-1-59259-152-7. オリジナルの29 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Bicalutamide (Casodex) in the treatment of prostate cancer”. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 4 (1): 37–48. (February 2004). doi:10.1586/14737140.4.1.37. PMID 14748655. "In contrast, the incidence of diarrhea was comparable between the bicalutamide and placebo groups (6.3 vs. 6.4%, respectively) in the EPC program [71]."

- ^ “Development and validation of a highly sensitive LC-MS/MS-ESI method for the determination of bicalutamide in mouse plasma: application to a pharmacokinetic study”. Biomedical Chromatography 26 (12): 1589–95. (2012). doi:10.1002/bmc.2736. PMID 22495777.

- ^ Anderson, Philip O.; Knoben, James E.; Troutman, William G. (22 August 2001). Handbook of Clinical Drug Data. 128. McGraw Hill Professional. 245. ISBN 978-0-07-138942-6. PMC 1875767. PMID 20313924. "With an oral dose of 50 mg/day, bicalutamide attains a peak serum level of 8.9 mg/L (21 μmol/L) 31 hr after a dose at steady state. CI of (R)-bicalutamide is 0.32 L/hr. The active (R)-enantiomer of bicalutamide is oxidized to an inactive metabolite, which, like the inactive (S)-enantiomer, is glucuronidated and cleared rapidly by elimination in the urine and feces.165"

- ^ a b “Nonsteroidal selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs): dissociating the anabolic and androgenic activities of the androgen receptor for therapeutic benefit”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 52 (12): 3597–617. (June 2009). doi:10.1021/jm900280m. PMID 19432422.

- ^ Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1372–1373. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. オリジナルの3 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “The response of advanced prostatic cancer to a new non-steroidal antiandrogen: results of a multicenter open phase II study of Casodex. European/Australian Co-operative Group”. European Urology 18 Suppl 3: 18–21. (1990). doi:10.1159/000463973. PMID 2094607.

- ^ The United States Patents Quarterly. Associated Industry Publications. (1997)

- ^ Chaurasiya, Akash; Singh, Ajeet Kumar; Upadhyay, Satish Chandra; Asati, Dinesh; Ahmad, Farhan Jalees; Mukherjee, Rama; Khar, Roop Krishen (2012). “Lipidic Nanocarrier for Oral Bioavailability Enhancement of an Anticancer Agent: Formulation Design and Evaluation”. Advanced Science Letters 11 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1166/asl.2012.2170. ISSN 1936-6612.

- ^ “Combined androgen blockade: an update”. The Urologic Clinics of North America 33 (2): 161–6, v–vi. (May 2006). doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2005.12.001. PMID 16631454.

- ^ “Exciting Therapies Ahead in Prostate Cancer”. P & T 40 (8): 530–1. (August 2015). PMC 4517537. PMID 26236143.

- ^ Denis, Louis (6 December 2012). Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer: A Key to Tailored Endocrine Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 128, 158, 203. ISBN 978-3-642-45745-6

- ^ “Antiandrogen monotherapy: a new form of treatment for patients with prostate cancer”. Urology 58 (2 Suppl 1): 16–23. (2001). doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01237-7. PMID 11502439.

- ^ “Bicalutamide: in early-stage prostate cancer”. Drugs 62 (17): 2471–79; discussion 2480–1. (2002). doi:10.2165/00003495-200262170-00006. PMID 12421104.

- ^ Jasmin, Claude; Capanna, Rodolfo; Coia, Lawrence; Coleman, Robert; Saillant, Gerard (27 September 2005). Textbook of Bone Metastases. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 493–. ISBN 978-0-470-01160-7

- ^ Bowsher, Winsor; Carter, Adam (15 April 2008). Challenges in Prostate Cancer. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-1-4051-7177-9

- ^ “Pharmacotherapy for prostate cancer: the role of hormonal treatment”. Discovery Medicine 7 (39): 118–24. (2007). PMID 18093474.

- ^ United Nations (2005). Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption And/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted Or Not Approved by Governments: Pharmaceuticals. United Nations Publications. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-92-1-130241-7

- ^ Bono, Aldo V (2004). “Overview of Current Treatment Strategies in Prostate Cancer”. European Urology Supplements 3 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1016/j.eursup.2003.12.002. "The Canadian Health Authorities have withdrawn the approval for antiandrogen monotherapy with bicalutamide for the treatment of localised prostate cancer [5]. Several European countries have also withdrawn approval for bicalutamide for this indication."

- ^ Nargund, Vinod H.; Raghavan, Derek; Sandler, Howard M. (17 January 2015). Urological Oncology. Springer. pp. 823–. ISBN 978-0-85729-482-1. "On the other hand, the 150 mg dose of bicalutamide has been associated with some safety concerns, such as a higher death rate when added to active surveillance in the early prostate cancer trialists group study [29], which has led the United States and Canada to recommend against prescribing the 150 mg dose [30]."

外部リンク[編集]

- “Bicalutamide”. Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2021年5月27日閲覧。