サイクリン依存性キナーゼ6

サイクリン依存性キナーゼ6(サイクリンいぞんせいキナーゼ6、英: Cyclin-dependent kinase 6、略称: CDK6)は、ヒトではCDK6遺伝子にコードされる酵素である[5][6]。この遺伝子によってコードされるタンパク質はサイクリン依存性キナーゼ(CDK)ファミリーのメンバーであり、サイクリン(サイクリンD)やサイクリン依存性キナーゼ阻害因子によって調節される[7]。CDKファミリーのメンバーは、出芽酵母Saccharomyces cerevisiaeのcdc28、分裂酵母Schizosaccharomyces pombeのcdc2の遺伝子産物と高度に類似している。

CDK6はサイクリン/CDK複合体の触媒サブユニットとして機能し、細胞周期のG1期ならびにG1/S期の移行に重要である。サイクリンDはキナーゼの活性化を行うサブユニットである[8]。このキナーゼの活性はG1期に最初に出現し、D型サイクリンなどの調節サブユニットやINK4ファミリーのCDK阻害因子によって制御される[7]。このキナーゼは、CDK4と同様にがん抑制因子であるRbタンパク質をリン酸化して調節するため、がんの発生に重要なタンパク質となっている[8]。

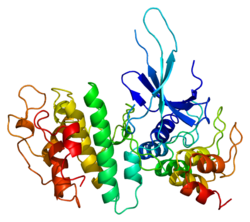

構造[編集]

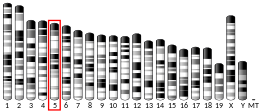

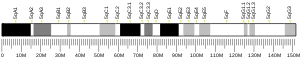

CDK6はCDKファミリーのなかでも特にCDK4と類似している。CDKファミリーは真核生物に保存されているが、CDK4/6は後生動物のみで保存されている[9]。ヒトのCDK6遺伝子は7番染色体に位置している。遺伝子は231,706塩基対にわたり、326アミノ酸からなるタンパク質をコードしている[6]。この遺伝子の発現の変化は複数種のがんで観察されている[6]。このタンパク質には、ATP結合ポケット、阻害または活性化リン酸化部位、PSTAIRE様サイクリン結合ドメイン、活性化Tループモチーフが存在する[8]。サイクリンがPSTAIREヘリックスに結合すると、CDK6タンパク質のコンフォメーションが変化してリン酸化モチーフが露出する[8]。CDK6は細胞質にも核にも存在するが、活性型の複合体は増殖中の細胞の核に存在している[8]。

機能[編集]

細胞周期[編集]

1994年にMatthew MeyersonとEd Harlowは、CDK4ときわめて類似した遺伝子の産物について研究を行った[7]。このPLSTIREと名付けられていた遺伝子から翻訳されるタンパク質は、CDK4と同じくサイクリンD1、D2、D3と相互作用したが、CDK4とは別物であった。その後、このタンパク質はCDK6へと改名された[7]。哺乳類細胞では、CDK6はG1期の初期にサイクリンD1、D2、D3との相互作用を介して細胞周期の進行を活性化する[7][10]。この酵素によって遺伝子発現には多くの変化が生じる[11]。サイクリンDと複合体を形成した後、CDK6はRbタンパク質をリン酸化する[12]。このリン酸化の後、Rbタンパク質は結合パートナーの転写活性化因子E2Fを解離し、解離したE2FはDNA複製に関与する遺伝子群を活性化する[13]。CDK6複合体は、分裂促進因子や成長因子といった外部シグナルに依存したG1期の初期から、その後の非依存的な段階への切り替えのポイント(R点)の保証を行っている[14]。

CDK6はG1期からS期への移行の制御に重要である[7]。しかし近年、全ての細胞種の増殖にCDK6の存在が必要不可欠なわけではないという証拠が得られている[15]。CDK6の役割の重要性は細胞種によって異なる可能性があり、CDK4やCDK2がその役割を補償して機能している可能性がある[15][16]。

細胞の発生[編集]

CDK6のノックアウトマウスでは造血機能不全となるが、他の組織は正常に発生する[15]。このことは、血液の構成要素の発生においてはCDK6にさらなる役割が存在していることを示唆している[15]。CDK6にはキナーゼ活性と関係のない他の機能も存在する[17]。例えば、CDK6はT細胞の分化に関与しており、分化の阻害因子として機能する[17]。CDK6とCDK4には71%のアミノ酸同一性があるが、この役割はCDK6に特有のものである[17]。また、CDK6は他の細胞系譜の発生にも重要であることが判明している。CDK6はアストロサイトの形態変化や[18]、他の幹細胞の発生にも関与している[8][13]。

DNA保護[編集]

CDK6にはCDK4とは異なる重要な役割が存在し、p53やp130といったアポトーシスに関与するタンパク質の蓄積に関与している。この蓄積はアポトーシス促進経路を活性化し、DNA損傷が存在する細胞が分裂を開始することを防いでいる[19]。

代謝の恒常性[編集]

CDK6は細胞の代謝制御にも関与している。CDK6とCDK4の阻害によって、ペントースリン酸経路の酸化過程と非酸化過程との間のバランスが失われる。また、CDK6とCDK4が過剰発現しているがん細胞ではこの経路に変化が生じていることが知られている[20]。CDK4とCDK6の過剰発現は、がん細胞に細胞の代謝異常という新たな特性を付与する[20]。

中心体の安定性[編集]

CDK6は中心体と結合し、神経細胞の分裂と細胞周期を制御している。これらの発生系譜でCDK6に変異が生じている場合、中心体の適切な分配が行われず、染色体の数的異常などが生じ、原発性小頭症などの健康問題が生じる[21]。

調節機構[編集]

CDK6は、主にサイクリンD1、D2、D3との結合によって正に調節されている。これらのD型サイクリンが存在しないときにはCDKは活性型でなく、Rbなどの基質をリン酸化することはない[22]。CDK6の活性化にはさらに177番のスレオニン残基のリン酸化が必要であり、このリン酸化はCDK活性化キナーゼ(CAK)によって行われる[23]。さらに、CDK6はカポジ肉腫関連ヘルペスウイルスによってもリン酸化されて活性化され、CDK6の過剰な活性化と制御を受けない細胞増殖が促進される[24]。

CDK6は、CDK阻害因子(CKI)との結合によって負に調節される[25]。p21、p27といったCIP/KIPファミリーのメンバーはサイクリン-CDK複合体に対して作用し、触媒ドメインに結合して阻害を行う[13][23][26]。p15、p16、p18、p19といったINK4ファミリーのメンバーはCDK6単量体に結合し、サイクリンとの複合体の形成を阻害する[27][28]。

臨床的意義[編集]

CDK6は細胞増殖を活性化するプロテインキナーゼであり、細胞周期の進行の制限の重要なポイントに関与している[29]。そのため、CDK6や他のG1期調節因子は、腫瘍の80–90%以上でバランスが失われていることが知られている[22]。子宮頸がん細胞では、CDK6の機能にはp16阻害因子を介した間接的な変化が起こっていることが示されている[28]。また、CDK6は薬剤耐性を示す腫瘍で過剰発現しており、悪性神経膠腫はCDK6の過剰発現変異が存在する場合、テモゾロミドを用いた化学療法に対する抵抗性を示す[30]。同様に、CDK6の過剰発現は、乳がんでの抗エストロゲン薬フルベストラントを用いたホルモン療法に対する抵抗性とも関係している[31]。

がん[編集]

正常な細胞周期調節の喪失は、がんのさまざまな特性が生じる第一段階である。CDK6の変化は、細胞のエネルギー調節異常、増殖シグナルの維持、成長抑制因子の回避、血管新生の誘導といったがんの特性に対し、直接的・間接的に影響を与える[22]。例えばリンパ系腫瘍においては、CDK6の調節異常は血管新生を増大させ、重要な役割を果たすことが示されている[27]。CDK6は、染色体の変化やエピジェネティックな調節の異常によってアップレギュレーションが起こっている[22]。さらに、CDK6はゲノム不安定性やがん抑制遺伝子のダウンレギュレーションによって変化している可能性もあり、これらもがんの特性である[32]。

髄芽腫[編集]

髄芽腫は小児の脳腫瘍の最も一般的な要因である[33]。これらのがんの約1/3ではCDK6のアップレギュレーションがみられ、この疾患の予後の悪さの指標となる[33]。CDK6の変化が生じることが一般的なため、これらの細胞系譜特異的にCDK6をダウンレギュレーションする方法が模索されている。In vitroの条件では、miR-124が髄芽腫と膠芽腫の細胞でがんの進行を制御する[33]。さらにラットモデルにおいても、miR-124によって腫瘍異種移植片の成長が減少することが示されている[33]。

薬剤標的として[編集]

CDK6やCDK4を直接標的としたがん治療は注意を要するが、それはこれらの酵素が正常細胞でも同様に細胞周期に重要な役割を果たしているためである[33]。さらに、これらのタンパク質を標的とした低分子は薬剤耐性を強化させる可能性がある[33]。CDK6を制御する間接的な機構として、CDK6に高い親和性で結合するがキナーゼ活性を誘導しない、変異型サイクリンDを利用する方法がある[34]。この機構の研究はラットの乳腺細胞の腫瘍形成に関して行われているが、ヒトの患者での臨床的効果は確認されていない[34]。

相互作用[編集]

CDK6は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000105810 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000040274 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “A family of human cdc2-related protein kinases”. The EMBO Journal 11 (8): 2909–17. (Aug 1992). doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05360.x. PMC 556772. PMID 1639063.

- ^ a b c “Entrez Gene: CDK6 cyclin-dependent kinase 6”. 2020年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f Meyerson, M; Harlow, E (1994). “Identification of G1 Kinase Activity for cdk6, a Novel Cyclin D Partner”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 14 (3): 2077–86. doi:10.1128/MCB.14.3.2077. PMC 358568. PMID 8114739.

- ^ a b c d e f “Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: roles beyond cell cycle regulation”. Development 140 (15): 3079–93. (Aug 2013). doi:10.1242/dev.091744. PMID 23861057.

- ^ Liu, Ji; Kipreos, Edward T. (2000). “Evolution of Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDKs) and CDK-Activating Kinases (CAKs): Differential Conservation of CAKs in Yeast and Metazoa”. Molecular Biology and Evolution 17 (7): 1061–74. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026387. PMID 10889219.

- ^ Harvey Lodish et al., Molecular Cell Biology. 4th Edition., 2000, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21497/.

- ^ “Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases”. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 14 (8): 518–28. (Aug 2013). doi:10.1038/nrm3629. PMC 4569015. PMID 23877564.

- ^ “Differential regulation of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein by G(1) cyclin-dependent kinase complexes in vivo”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 21 (14): 4773–84. (Jul 2001). doi:10.1128/MCB.21.14.4773-4784.2001. PMC 87164. PMID 11416152.

- ^ a b c “Beyond the cell cycle: a new role for Cdk6 in differentiation”. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 97 (3): 485–93. (Feb 2006). doi:10.1002/jcb.20712. PMID 16294322.

- ^ Bartek, J; Lukas, J (2001). “Mammalian G1- and S-Phase Checkpoints in Response to DNA Damage”. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 13 (6): 738–47. doi:10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00280-5. PMID 11698191.

- ^ a b c d Kozar, Katarzyna; Sicinski, Piotr (2005-03). “Cell cycle progression without cyclin D-CDK4 and cyclin D-CDK6 complexes”. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 4 (3): 388–391. doi:10.4161/cc.4.3.1551. ISSN 1551-4005. PMID 15738651.

- ^ “Mammalian cells cycle without the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6”. Cell 118 (4): 493–504. (Aug 2004). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.002. PMID 15315761.

- ^ a b c Grossel, Martha J.; Hinds, Philip W. (2006-02). “From cell cycle to differentiation: an expanding role for cdk6”. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 5 (3): 266–270. doi:10.4161/cc.5.3.2385. ISSN 1551-4005. PMID 16410727.

- ^ Ericson, Karen K.; Krull, David; Slomiany, Peter; Grossel, Martha J. (2003-07). “Expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 6, but not cyclin-dependent kinase 4, alters morphology of cultured mouse astrocytes”. Molecular cancer research: MCR 1 (9): 654–664. ISSN 1541-7786. PMID 12861051.

- ^ “Accumulation of high levels of the p53 and p130 growth-suppressing proteins in cell lines stably over-expressing cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (cdk6)”. Oncogene 20 (23): 2889–99. (May 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204396. PMID 11420701.

- ^ a b “Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 control tumor progression and direct glucose oxidation in the pentose cycle”. Metabolomics 8 (3): 454–64. (Jun 2012). doi:10.1007/s11306-011-0328-x. PMC 3361763. PMID 22661920.

- ^ Hussain, Muhammad S (2013). “CDK6 Associates with the Centrosome during Mitosis and Is Mutated in a Large Pakistani Family with Primary Microcephaly”. Human Molecular Genetics 22 (25): 5199–5214. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt374. PMID 23918663.

- ^ a b c d “Targeting cell cycle regulation in cancer therapy”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 138 (2): 255–71. (May 2013). doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.011. PMID 23356980.

- ^ a b LaBaer, J (1997). “New Functional Activities for the p21 Family of CDK Inhibitors”. Genes & Development 11 (7): 847–62. doi:10.1101/gad.11.7.847. PMID 9106657.

- ^ “The N-terminal peptide of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-cyclin determines substrate specificity”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (12): 11165–74. (Mar 2005). doi:10.1074/jbc.M408887200. PMID 15664993.

- ^ Nurse, P (2000). “A Long Twentieth Century of the Cell Cycle and beyond”. Cell 100 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81684-0. PMID 10647932.

- ^ “Regulated activating Thr172 phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4(CDK4): its relationship with cyclins and CDK "inhibitors"”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 26 (13): 5070–85. (Jul 2006). doi:10.1128/MCB.02006-05. PMC 1489149. PMID 16782892.

- ^ a b “A kinase-independent function of CDK6 links the cell cycle to tumor angiogenesis”. Cancer Cell 24 (2): 167–81. (Aug 2013). doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2013.07.012. PMC 3743049. PMID 23948297.

- ^ a b Khleif, S N (1996). “Inhibition of Cyclin D-CDK4/CDK6 Activity Is Associated with an E2F-Mediated Induction of Cyclin Kinase Inhibitor Activity”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (9): 4350–54. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.9.4350. PMC 39540. PMID 8633069.

- ^ “Tumour selective targeting of cell cycle kinases for cancer treatment”. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 13 (4): 529–35. (Aug 2013). doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.03.012. PMID 23597425.

- ^ “Knockdown of CDK6 enhances glioma sensitivity to chemotherapy”. Oncology Reports 28 (3): 909–14. (Sep 2012). doi:10.3892/or.2012.1884. PMID 22736304.

- ^ “Fulvestrant induces resistance by modulating GPER and CDK6 expression: implication of methyltransferases, deacetylases and the hSWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex”. British Journal of Cancer 109 (10): 2751–62. (Nov 2013). doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.583. PMC 3833203. PMID 24169358.

- ^ “Genomic instability--an evolving hallmark of cancer”. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 11 (3): 220–28. (Mar 2010). doi:10.1038/nrm2858. PMID 20177397.

- ^ a b c d e f “Expression of miR-124 inhibits growth of medulloblastoma cells”. Neuro-Oncology 15 (1): 83–90. (Jan 2013). doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos281. PMC 3534424. PMID 23172372.

- ^ a b “Cyclin D1-dependent kinase activity in murine development and mammary tumorigenesis”. Cancer Cell 9 (1): 13–22. (Jan 2006). doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.019. PMID 16413468.

- ^ “Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry”. Molecular Systems Biology 3: 89. (2007). doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948. PMID 17353931.

- ^ “Growth suppression by p18, a p16INK4/MTS1- and p14INK4B/MTS2-related CDK6 inhibitor, correlates with wild-type pRb function”. Genes & Development 8 (24): 2939–52. (Dec 1994). doi:10.1101/gad.8.24.2939. PMID 8001816.

- ^ “Structural basis of inhibition of CDK-cyclin complexes by INK4 inhibitors”. Genes & Development 14 (24): 3115–25. (Dec 2000). doi:10.1101/gad.851100. PMC 317144. PMID 11124804.

- ^ a b “Cdk6-cyclin D3 complex evades inhibition by inhibitor proteins and uniquely controls cell's proliferation competence”. Oncogene 20 (16): 2000–9. (Apr 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204375. PMID 11360184.

- ^ “Regulation of CDK4 activity by a novel CDK4-binding protein, p34(SEI-1)”. Genes & Development 13 (22): 3027–33. (Nov 1999). doi:10.1101/gad.13.22.3027. PMC 317153. PMID 10580009.

- ^ “Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 14 (3): 2077–86. (Mar 1994). doi:10.1128/MCB.14.3.2077. PMC 358568. PMID 8114739.

- ^ “Inhibition of pRb phosphorylation and cell-cycle progression by a 20-residue peptide derived from p16CDKN2/INK4A”. Current Biology 6 (1): 84–91. (Jan 1996). doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00425-6. PMID 8805225.

- ^ “Structural basis for inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk6 by the tumour suppressor p16INK4a”. Nature 395 (6699): 237–43. (Sep 1998). doi:10.1038/26155. PMID 9751050.

- ^ “CAK-independent activation of CDK6 by a viral cyclin”. Molecular Biology of the Cell 12 (12): 3987–99. (Dec 2001). doi:10.1091/mbc.12.12.3987. PMC 60770. PMID 11739795.

- ^ a b “Dephosphorylation of human cyclin-dependent kinases by protein phosphatase type 2C alpha and beta 2 isoforms”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (44): 34744–9. (Nov 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M006210200. PMID 10934208.

関連文献[編集]

- “Initial assessment of human gene diversity and expression patterns based upon 83 million nucleotides of cDNA sequence”. Nature 377 (6547 Suppl): 3–174. (Sep 1995). PMID 7566098.

- “Both p16 and p21 families of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors block the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinases by the CDK-activating kinase”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 270 (31): 18195–7. (Aug 1995). doi:10.1074/jbc.270.31.18195. PMID 7629134.

- “Regulation of synthesis and activity of the PLSTIRE protein (cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (cdk6)), a major cyclin D-associated cdk4 homologue in normal human T lymphocytes”. Journal of Immunology 154 (12): 6275–84. (Jun 1995). PMID 7759865.

- “Chromosomal mapping of members of the cdc2 family of protein kinases, cdk3, cdk6, PISSLRE, and PITALRE, and a cdk inhibitor, p27Kip1, to regions involved in human cancer”. Cancer Research 55 (6): 1199–205. (Mar 1995). PMID 7882308.

- “Growth suppression by p18, a p16INK4/MTS1- and p14INK4B/MTS2-related CDK6 inhibitor, correlates with wild-type pRb function”. Genes & Development 8 (24): 2939–52. (Dec 1994). doi:10.1101/gad.8.24.2939. PMID 8001816.

- “Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 14 (3): 2077–86. (Mar 1994). doi:10.1128/MCB.14.3.2077. PMC 358568. PMID 8114739.

- “Inhibition of pRb phosphorylation and cell-cycle progression by a 20-residue peptide derived from p16CDKN2/INK4A”. Current Biology 6 (1): 84–91. (Jan 1996). doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00425-6. PMID 8805225.

- “Normalization and subtraction: two approaches to facilitate gene discovery”. Genome Research 6 (9): 791–806. (Sep 1996). doi:10.1101/gr.6.9.791. PMID 8889548.

- “Interaction between Cdc37 and Cdk4 in human cells”. Oncogene 14 (16): 1999–2004. (Apr 1997). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201036. PMID 9150368.

- “Rapid nuclear translocation and increased activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 after T cell activation”. Journal of Immunology 158 (11): 5146–54. (Jun 1997). PMID 9164930.

- “Hypo-phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) by cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes results in active pRb”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94 (20): 10699–704. (Sep 1997). doi:10.1073/pnas.94.20.10699. PMC 23451. PMID 9380698.

- “Characterization of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitory domain of the INK4 family as a model for a synthetic tumour suppressor molecule”. Oncogene 16 (5): 587–96. (Feb 1998). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201580. PMID 9482104.

- “Chemical transformation of mouse liver cells results in altered cyclin D-CDK protein complexes”. Carcinogenesis 19 (6): 1093–102. (Jun 1998). doi:10.1093/carcin/19.6.1093. PMID 9667749.

- “Structural basis for inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk6 by the tumour suppressor p16INK4a”. Nature 395 (6699): 237–43. (Sep 1998). doi:10.1038/26155. PMID 9751050.

- “Crystal structure of the complex of the cyclin D-dependent kinase Cdk6 bound to the cell-cycle inhibitor p19INK4d”. Nature 395 (6699): 244–50. (Sep 1998). doi:10.1038/26164. PMID 9751051.

- “Multistep regulation of DNA replication by Cdk phosphorylation of HsCdc6”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (11): 6193–8. (May 1999). doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6193. PMC 26858. PMID 10339564.

- “Biologic and biochemical analyses of p16(INK4a) mutations from primary tumors”. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 91 (18): 1569–74. (Sep 1999). doi:10.1093/jnci/91.18.1569. PMID 10491434.

- “Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1”. Cell 98 (6): 859–69. (Sep 1999). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81519-6. PMID 10499802.

- “cdk6 can shorten G(1) phase dependent upon the N-terminal INK4 interaction domain”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 (42): 29960–7. (Oct 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.42.29960. PMID 10514479.

関連項目[編集]

外部リンク[編集]

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 6 - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス(英語)