「ロタウイルス」の版間の差分

Karasunoko (会話 | 投稿記録) m →構造 |

|||

| (3人の利用者による、間の20版が非表示) | |||

| 13行目: | 13行目: | ||

一般に'''乳児下痢症'''・嘔吐下痢症の原因としても知られている。[[アメリカ合衆国]]では年間50万人以上が主に下痢症状で受診し、特に小児は重篤な下痢を起こし易く、罹患患者の10%は入院となる。地域差があると考えられるが世界で毎年約70万人程度が亡くなっていると考えられている<ref name="moden_m">[http://www.eiken.co.jp/modern_media/backnumber/pdf/MM0612-01.pdf ロタウイルスの最近の話題] モダンメディア 2006年12月号(第52巻12号)</ref>。 |

一般に'''乳児下痢症'''・嘔吐下痢症の原因としても知られている。[[アメリカ合衆国]]では年間50万人以上が主に下痢症状で受診し、特に小児は重篤な下痢を起こし易く、罹患患者の10%は入院となる。地域差があると考えられるが世界で毎年約70万人程度が亡くなっていると考えられている<ref name="moden_m">[http://www.eiken.co.jp/modern_media/backnumber/pdf/MM0612-01.pdf ロタウイルスの最近の話題] モダンメディア 2006年12月号(第52巻12号)</ref>。 |

||

== |

==徴候と症状== |

||

[[ロタウイルス性腸炎]]は軽度から重度の至る疾患で、[[吐き気]]、[[嘔吐]]、水様性の下痢、軽い[[発熱]]を特徴とする。幼児がロタウイルスに感染した場合、症状が現れるまでの[[潜伏期間|潜伏期]] (incubation period) は約2日程度である<ref name="pmid10532018">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hochwald C, Kivela L |title=Rotavirus vaccine, live, oral, tetravalent (RotaShield) |journal=Pediatr. Nurs. |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=203–4, 207 |year=1999|pmid=10532018}}</ref>。腸炎は急性経過をとり、発症後しばしば最初に嘔吐が認められ、その後4日から8日程度の重篤な下痢が続く。[[脱水 (医療)|脱水症状]]が他の細菌性下痢症に比べ発生しやすく、これはロタウイルス感染症の主要な死因でもある<ref name="pmid1962726">{{cite journal|vauthors=Maldonado YA, Yolken RH |title=Rotavirus|journal=Baillieres Clin. Gastroenterol.|volume=4|issue=3|pages=609–25|year=1990|pmid=1962726|doi=10.1016/0950-3528(90)90052-I}}</ref>。 |

|||

内殻タンパク (VP6) の抗原性によりA~G群に分類される。 |

|||

* A群はヒト、サル、ウマ、トリ、イヌ、ブタ、マウス |

|||

* B群はヒト、ブタ、ウシ、ラット |

|||

* C群はヒト、ブタ |

|||

* D群はブタ、ウサギ、鳥類 |

|||

* E群はブタ |

|||

* FおよびG群は鳥類を宿主とする |

|||

A群ロタウイルスの感染は生涯を通じて起こりうるが、初感染時に通常認められる症状は、2回目以降では軽微、あるいは不顕性である<ref name="pmid16860702">{{cite journal |vauthors=Glass RI, Parashar UD, Bresee JS, Turcios R, Fischer TK, Widdowson MA, Jiang B, Gentsch JR |title=Rotavirus vaccines: current prospects and future challenges |journal=Lancet |volume=368 |issue=9532 |pages=323–32 |date=July 2006 |pmid=16860702 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68815-6 }}</ref><ref name="pmid9015109">{{cite journal|author=Bishop RF|title=Natural history of human rotavirus infection|journal=Arch. Virol. Suppl.|volume=12|issue=|pages=119–28|year=1996|pmid=9015109}}</ref>。2回目以降の感染時の症状の減弱は免疫系による防御に由来する<ref name="isbn0-471-49663-4"3>{{cite book |author=Offit PA|authorlink=Paul Offit|title=Gastroenteritis viruses|isbn=0-471-49663-4 |publisher=Wiley |location=New York |year=2001 |pages=106–124}}</ref><ref name="pmid19252425">{{cite journal |author=Ward R |title=Mechanisms of protection against rotavirus infection and disease |journal=The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal |volume=28 |issue=3 Suppl |pages=S57–9 |date=March 2009 |pmid=19252425 |doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967c16}}</ref>。そのため顕性感染は2歳以下の乳幼児で多く、45歳まで年齢を重ねるにつれて減少する<ref name="isbn0-89603-736-3"2>{{cite book |vauthors=Ramsay M, Brown D|editor1=Desselberger, U. |editor2=Gray, James |title=Rotaviruses: methods and protocols|publisher=Humana Press |location=Totowa, NJ |year=2000|page= 217 |isbn=0-89603-736-3}}Free ebook [http://bookos.org/g/James%20Gray%20and%20Ulrich%20Desselberger]</ref>。新生児の感染はよくみられるが、軽微か不顕性である事が比較的多く<ref name="pmid18838873">{{cite journal |vauthors=Grimwood K, Lambert SB |title=Rotavirus vaccines: opportunities and challenges |journal=Human Vaccines |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=57–69 |date=February 2009 |pmid=18838873 |doi=10.4161/hv.5.2.6924 |url=http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/hv/abstract.php?id=6924}}</ref>、最も重症化しやすいのは6ヶ月から10歳の乳幼児・小児や高齢者、あるいは[[免疫不全]]症患者である。幼少期に獲得する免疫により、ほとんどの成人はロタウイルスに抵抗性である。成人の胃腸炎は通常他の病原体によるが、一方で成人の不顕性感染が集団における感染経路の維持に寄与している可能性がある<ref name="pmid3037675">{{cite journal |

|||

== 臨床像 == |

|||

|author=Hrdy DB |

|||

感染経路は全て経口。 |

|||

|title=Epidemiology of rotaviral infection in adults |

|||

* 潜伏期24~72時間(1~3日)、下痢症状は3~9日継続し乳児のウイルス性[[下痢]]症・[[感染性胃腸炎]]の原因ウイルスとして重要。中枢神経にも影響し合併症として、[[痙攣]]、[[脳炎]]、[[髄膜炎]]、[[脳症]]<ref>[http://dx.doi.org/10.4264/numa.67.304 ロタウイルス感染に関連した急性脳症の 1例] 日大医学雑誌 Vol.67 (2008) No.5 P304-308</ref>、[[ライ症候群]]、[[ギラン・バレー症候群]]、出血性ショック脳症症候群をおこすこともある。 |

|||

|journal=Rev. Infect. Dis. |

|||

* 冬季に流行し、多くは白色の水様下痢を生じ白色便性下痢症と呼ばれることもあるが、白色になるとは限らない<ref>[http://medical.nikkeibp.co.jp/leaf/mem/pub/report/t189/201212/528123.html?ref=RL2 【ロタウイルス感染症】急変リスク高い胃腸炎] 日経メディカルオンライン 記事:2012年12月19日 閲覧:2014年1月7日</ref>。便の状態は、「米のとぎ汁のよう」と表現される事もある。激しい下痢のため脱水に陥りやすく、経口補水や輸液により水分の補給を行う。 |

|||

|volume=9 |

|||

* 糞口感染を起こすことも多く、感染予防には手洗いが重要である。 |

|||

|issue=3 |

|||

* 医療従事者は、患者の嘔吐物や糞便を処理するときのみでなく、患者の処置や診察時に標準予防策および接触感染予防策を講じて、他の患者に接する前および他のエリアに移動する前には必ず手袋やガウンを外し、手洗いを行うようにしなければならない。(universal precaution) |

|||

|pages=461–9 |

|||

* 特異的な治療法はなく、対症療法が行われる。下痢止め薬は症状の回復を遅らせるため使用しない。 |

|||

|year=1987 |

|||

|pmid=3037675 |

|||

|doi=10.1093/clinids/9.3.461 |

|||

}}</ref>。 |

|||

== |

==ウイルス学== |

||

糞便中ロタウイルス抗原を迅速に検査できるようになった。(ロタ診断薬:ラピッドエスピー《ロタ》(DSファーマバイオメディカル株式会社)、ラピッドテスタ<sup>®</sup>ロタ・アデノなど) |

|||

===ロタウイルスの型=== |

|||

ロタウイルスはAからH群までの8つの種に分かれる<ref>{{cite|url=http://ictvonline.org/virustaxonomy.asp |title=Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release |publisher= International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV)}}</ref>。ヒトは主にA群、B群、C群に感染し、特にA群への感染が一般的である<ref name=NIID/>。E群やH群はブタに、D群、E群、F群は鳥類に感染する<ref name="pmid21801631">{{cite journal |vauthors=Wakuda M, Ide T, Sasaki J, Komoto S, Ishii J, Sanekata T, Taniguchi K |title=Porcine rotavirus closely related to novel group of human rotaviruses |journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases |volume=17 |issue=8 |pages=1491–3 |year=2011 |pmid=21801631 |pmc=3381553 |doi=10.3201/eid1708.101466 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid24960190">{{cite journal |vauthors=Marthaler D, Rossow K, Culhane M, Goyal S, Collins J, Matthijnssens J, Nelson M, Ciarlet M |title=Widespread rotavirus H in commercially raised pigs, United States |journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases |volume=20 |issue=7 |pages=1195–8 |year=2014 |pmid=24960190 |pmc=4073875 |doi=10.3201/eid2007.140034 |url=}}</ref>。A群ロタウイルスはさらに複数の株に分かれ、これを[[血清型]]と呼ぶ<ref name="pmid19252426">{{cite journal |author=O'Ryan M |title=The ever-changing landscape of rotavirus serotypes |journal=The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal |volume=28 |issue=3 Suppl |pages=S60–2 |date=March 2009 |pmid=19252426 |doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967c29}}</ref>。血清型は[[インフルエンザウイルス]]と同様に2つの表面タンパク質の組み合わせによって命名される。[[糖タンパク質]]VP7がG血清型を、[[プロテアーゼ]]感受性タンパク質VP4がP血清型を決定する<ref name="pmid22284787">{{cite journal |author=Patton JT |title=Rotavirus diversity and evolution in the post-vaccine world |journal=Discovery Medicine |volume=13 |issue=68 |pages=85–97 |date=January 2012 |pmid=22284787 |url=http://www.discoverymedicine.com/John-T-Patton/2012/01/26/rotavirus-diversity-and-evolution-in-the-post-vaccine-world/ |pmc=3738915}}</ref>。G型を定義する遺伝子とP型を定義する遺伝子は別々に子孫ウイルスへ継がれるため、様々な組み合わせが生じる<ref name="pmid16397427">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Desselberger U, Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch J, Mrukowicz J, Rodrigo C, Giaquinto C, Vesikari T |title=Rotavirus types in Europe and their significance for vaccination |

|||

|journal=Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. |

|||

|volume=25 |

|||

|issue=1 Suppl. |

|||

|pages=S30–41 |

|||

|year=2006 |

|||

|pmid=16397427 |

|||

|url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?an=00006454-200601001-00005 |

|||

|doi=10.1097/01.inf.0000197707.70835.f3 |

|||

}}</ref>。 |

|||

===構造=== |

|||

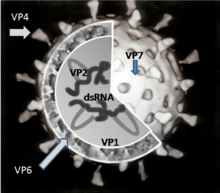

ロタウイルスの[[ゲノム]]は11分節に分かれる計18,555塩基対の二本鎖RNAである。各分節は一つの[[遺伝子]]であり、大きいものから順に1から11の番号が割り当てられている。各遺伝子は1種類の[[タンパク質]]をコードしているが、第9遺伝子分節は例外的に2つのタンパク質をコードする<ref name="isbn0-89603-736-3">{{cite book |author1=Desselberger, U. |author2=Gray, James |editor1=Desselberger, U. |editor2=Gray, James |title=Rotaviruses: methods and protocols|publisher=Humana Press |location=Totowa, NJ |year=2000|page=2 |isbn=0-89603-736-3 }}</ref>。RNAは外殻、内殻からなる二層の[[カプシド]]と、その内層に存在するコアの合わせて三層からなるタンパク質に包まれ<ref name="stmicrobiol"/>、コアを包むカプシドタンパク質の形状は正二十面体である。ウイルス粒子の粒子径は最大で76.4 nmであり<ref name="pmid16913048">{{cite journal |vauthors=Pesavento JB, Crawford SE, Estes MK, Prasad BV |title=Rotavirus proteins: structure and assembly |journal=Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. |volume=309 |pages=189–219 |year=2006 |pmid=16913048 |doi=10.1007/3-540-30773-7_7 |series=Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology |isbn=978-3-540-30772-3}}</ref><ref name="pmid8050286">{{cite journal |vauthors=Prasad BV, Chiu W |title=Structure of rotavirus |journal=Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. |volume=185 |pages=9–29 |year=1994 |pmid=8050286}}</ref>、[[エンベロープ (ウイルス)|エンベロープ]]を持たない。 |

|||

===タンパク質=== |

|||

6つのウイルスタンパク質 (VP) がウイルスの粒子を構成する。この構造タンパク質群はそれぞれVP1、VP2、VP3、VP4、VP6およびVP7と呼ばれる。構造タンパク質であるVPに加え、ロタウイルスは感染細胞の細胞内ではさらに非構造タンパク質 (NSP) を合成する。この非構造タンパク質はそれぞれNSP1、NSP2、NSP3、NSP4、NSP6およびNSP7と呼ばれる<ref name="pmid20684716">{{cite journal|author=Kirkwood CD|date=September 2010|title=Genetic and antigenic diversity of human rotaviruses: potential impact on vaccination programs|journal=The Journal of Infectious Diseases|volume=202|issue=Suppl|pages=S43–8|pmid=20684716|doi=10.1086/653548}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[Image:Rotavirus Structure.png|left|thumb|ロタウイルスの構造タンパク質の局在を表した模式図|alt=A cut-up image of a single rotavirus particle showing the RNA moecules surrounded by the VP6 protein and this in turn surrounded by the VP7 protein. The V4 protein protrudes from the surface of the spherical particel.]] |

|||

ロタウイルスゲノムにコードされる12の遺伝子のうち、6つは[[リボ核酸|RNA]]結合性タンパク質である<ref name="pmid7595370">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Patton JT |

|||

|title=Structure and function of the rotavirus RNA-binding proteins |

|||

|journal=J. Gen. Virol. |

|||

|volume=76 |

|||

|pages=2633–44 |

|||

|year=1995 |

|||

|pmid=7595370 |

|||

|url=http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/reprint/76/11/2633 |

|||

|format=PDF |

|||

|doi=10.1099/0022-1317-76-11-2633 |

|||

|issue=11 |

|||

}}</ref>。ロタウイルスの複製におけるこれらのタンパク質の役割は完全には理解されていないが、RNAの合成とウイルス粒子へのパッケージング、ゲノム複製の場への[[伝令RNA|mRNA]]輸送、mRNAの翻訳と遺伝子発現調節に関与すると考えられている<ref name="pmid11444036">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Patton JT |

|||

|title=Rotavirus RNA replication and gene expression |

|||

|journal=Novartis Found. Symp. |

|||

|volume=238 |

|||

|pages=64–77; discussion 77–81 |

|||

|year=2001 |

|||

|pmid=11444036 |

|||

|doi=10.1002/0470846534.ch5 |

|||

|series=Novartis Foundation Symposia |

|||

|isbn=9780470846537 |

|||

}}</ref>。 |

|||

====構造タンパク質==== |

|||

VP1はウイルス粒子のコア内に存在する[[RNAポリメラーゼ]]である<ref name="pmid17657346">{{cite journal |vauthors=Vásquez-del Carpió R, Morales JL, Barro M, Ricardo A, Spencer E |title=Bioinformatic prediction of polymerase elements in the rotavirus VP1 protein |journal=Biol. Res. |volume=39 |issue=4 |pages=649–59 |year=2006 |pmid=17657346 |doi=10.4067/S0716-97602006000500008 |url=http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-97602006000500008&tlng=en&lng=en&nrm=iso}}</ref>。感染細胞内でVP1はウイルスタンパク質の合成や新しく合成されたウイルス粒子のゲノムとなるRNA分節の複製に用いられるmRNAを合成する。 |

|||

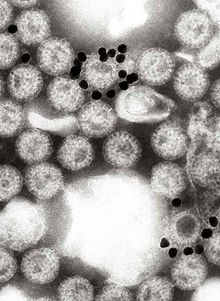

[[Image:Rotavirus with gold- labelled monoclonal antibody.jpg|left|thumb| |

|||

ロタウイルスの付着した金粒子の電子顕微鏡写真。小さい黒い円状の物質はロタウイルスのVP6に特異的な[[モノクローナル抗体]]によって覆われた金粒子である。|alt=An electron micrograph of many rotavirus particles, two of which have several smaller, black spheres which appear to be attached to them]] |

|||

VP2はウイルス粒子のコアを形成し、RNAと結合する<ref name="pmid17182692">{{cite journal |vauthors=Arnoldi F, Campagna M, Eichwald C, Desselberger U, Burrone OR |title=Interaction of rotavirus polymerase VP1 with nonstructural protein NSP5 is stronger than that with NSP2 |journal=J. Virol. |volume=81 |issue=5 |pages=2128–37 |year=2007 |pmid=17182692 |doi=10.1128/JVI.01494-06 |url=http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/content/full/81/5/2128 |pmc=1865955}}</ref>。 |

|||

VP3はコアの成分の1つで、[[グアニリルトランスフェラーゼ]]と呼ばれる酵素である。VP3は[[キャップ形成酵素]]であり、mRNAの転写後修飾として生じる[[5'キャップ]]の付加反応を触媒する<ref name="isbn0-12-375147-0">{{cite book |vauthors=Angel J, Franco MA, Greenberg HB |veditors=Mahy BW, Van Regenmortel MH |title=Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology |publisher=Academic Press |location=Boston |year=2009 |page=277 |isbn=0-12-375147-0}}</ref>。キャップ構造は[[核酸]]を分解する酵素であるヌクレアーゼからウイルスmRNAを保護することで、mRNAの安定化に寄与する<ref name="pmid20025612">{{cite journal |author=Cowling VH |title=Regulation of mRNA cap methylation |journal=Biochem. J. |volume=425 |issue=2 |pages=295–302 |date=January 2010 |pmid=20025612 |pmc=2825737 |doi=10.1042/BJ20091352}}</ref>。 |

|||

VP4はスパイク状の突起としてウイルス粒子の表面に存在する外殻タンパク質である<ref name="stmicrobiol"/><ref name="pmid16571811">{{cite journal |vauthors=Gardet A, Breton M, Fontanges P, Trugnan G, Chwetzoff S |title=Rotavirus spike protein VP4 binds to and remodels actin bundles of the epithelial brush border into actin bodies |journal=J. Virol. |volume=80 |issue=8 |pages=3947–56 |year=2006 |pmid=16571811 |doi=10.1128/JVI.80.8.3947-3956.2006 |url=http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/content/full/80/8/3947 |pmc=1440440}}</ref>。VP4は細胞表面の[[受容体]]と呼ばれる分子に結合し、ウイルスの細胞への侵入を引き起こす<ref name="pmid12234525">{{cite journal |vauthors=Arias CF, Isa P, Guerrero CA, Méndez E, Zárate S, López T, Espinosa R, Romero P, López S |title=Molecular biology of rotavirus cell entry |journal=Arch. Med. Res. |volume=33 |issue=4 |pages=356–61 |year=2002 |pmid=12234525 |doi=10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00374-0}}</ref>。VP4は腸管に発現している[[プロテアーゼ]]である[[トリプシン]]によって処理を受け、VP5*とVP8*に開裂する<ref name="pmid15010218">{{cite journal |vauthors=Jayaram H, Estes MK, Prasad BV |title=Emerging themes in rotavirus cell entry, genome organization, transcription and replication |journal=Virus Research |volume=101 |issue=1 |pages=67–81 |date=April 2004 |pmid=15010218 |doi=10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.007}}</ref>。VP4はウイルスの[[病原性]]を決定する因子であり、またロタウイルスのP型を決定する因子でもある<ref name="pmid12167342">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hoshino Y, Jones RW, Kapikian AZ |title=Characterization of neutralization specificities of outer capsid spike protein VP4 of selected murine, lapine, and human rotavirus strains |journal=Virology |volume=299 |issue=1 |pages=64–71 |year=2002 |pmid=12167342 |doi=10.1006/viro.2002.1474}}</ref>。 |

|||

VP6はカプシドの主成分で内殻を構成する<ref name="stmicrobiol"/>。[[抗原|抗原性]]が高く、ロタウイルスの種の同定に用いられる<ref name="pmid9015109"/>。また、VP6はA群ロタウイルス感染における検査に使用される<ref name="pmid6321549">{{cite journal |vauthors=Beards GM, Campbell AD, Cottrell NR, Peiris JS, Rees N, Sanders RC, Shirley JA, Wood HC, Flewett TH |title=Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays based on polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies for rotavirus detection |journal=J. Clin. Microbiol. |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=248–54 |date=1 February 1984|pmid=6321549 |url=http://jcm.asm.org/cgi/reprint/19/2/248 |format=PDF |pmc=271031 }}</ref>。 |

|||

VP7はウイルス粒子の外殻を形成する糖タンパク質である<ref name="stmicrobiol"/>。構造に関わる他、VP7はG型を決定し、VP4と共にロタウイルス感染に対する[[免疫系|免疫]]に関係する<ref name="pmid16913048"/>。 |

|||

====非構造タンパク質==== |

|||

NSP1は第5分節に由来する遺伝子産物で、非構造性のRNA結合タンパク質である<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hua J, Mansell EA, Patton JT |title=Comparative analysis of the rotavirus NS53 gene: conservation of basic and cysteine-rich regions in the protein and possible stem-loop structures in the RNA |journal=Virology |volume=196 |issue=1 |pages=372–8 |year=1993 |pmid=8395125 |doi=10.1006/viro.1993.1492}}</ref>。また、NSP1は[[インターフェロン]]に誘導される応答を阻害し、ウイルスの感染から細胞を守る[[自然免疫|自然免疫系]]の反応を抑える。NSP1は、感染細胞におけるインターフェロン産生の増強と、隣接細胞によって分泌されたインターフェロンに対する応答に必要な重要なシグナル分子を、[[プロテアソーム|プロテオソーム]]によって分解してしまう。分解の標的となる分子としては、インターフェロン遺伝子の転写に必要な[[IRF]]転写因子などがある<ref name=Arnold2016>{{cite journal |vauthors=Arnold MM |title=The Rotavirus Interferon Antagonist NSP1: Many Targets, Many Questions |journal=Journal of Virology |volume=90 |issue=11 |pages=5212–5 |year=2016 |pmid=27009959 |doi=10.1128/JVI.03068-15 |url=}}</ref>。 |

|||

NSP2は細胞質内封入体に蓄積するRNA結合タンパク質で、ゲノム複製に必要な分子である<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kattoura MD, Chen X, Patton JT |title=The rotavirus RNA-binding protein NS35 (NSP2) forms 10S multimers and interacts with the viral RNA polymerase |journal=Virology |volume=202 |issue=2 |pages=803–13 |year=1994 |pmid=8030243 |doi=10.1006/viro.1994.1402}}</ref><ref name="pmid15010217">{{cite journal |vauthors=Taraporewala ZF, Patton JT |title=Nonstructural proteins involved in genome packaging and replication of rotaviruses and other members of the Reoviridae |journal=Virus Res. |volume=101 |issue=1 |pages=57–66 |year=2004 |pmid=15010217 |doi=10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.006}}</ref>。 |

|||

NSP3は感染細胞内でウイルスmRNAに結合しており、細胞のタンパク質合成を遮断する役割を持つ<ref>{{cite journal |title=Rotavirus protein NSP3 (NS34) is bound to the 3' end consensus sequence of viral mRNAs in infected cells |

|||

|journal=J. Virol. |volume=67 |issue=6 |pages=3159–65 |date=1 June 1993|pmid=8388495 |url=http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/reprint/67/6/3159 |format=PDF |pmc=237654 |author = Poncet D, Aponte C, [[Jean Cohen|Cohen J]] }}</ref>。NSP3は宿主のmRNAからタンパク質を合成するために必要な2つの翻訳開始因子を不活化する。NSP3はまず、転写開始因子elF4FからポリA結合タンパク質 (PABP) を外してしまう。PABPは3' ポリA尾部を持つ転写産物からの効率的な翻訳に必要な因子で、宿主細胞の転写産物のほとんどに結合している。次にNSP3はelf2のリン酸化を促進することで、これを不活化する。ロタウイルスのmRNAはポリA尾部を欠いており、上記の2つの因子のいずれも翻訳に必要ではない<ref name="Lopez2012">{{cite journal|last1=López|first1=S|last2=Arias|first2=CF|title=Rotavirus-host cell interactions: an arms race.|journal=Current Opinion in Virology|date=August 2012|volume=2|issue=4|pages=389–98|doi=10.1016/j.coviro.2012.05.001|pmid=22658208}}</ref>。 |

|||

NSP4は下痢を引き起こすウイルス性の[[エンテロトキシン]]で、ウイルス性のエンテロトキシンとしては初めて発見されたものである<ref name="pmid19114772">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hyser JM, Estes MK |title=Rotavirus vaccines and pathogenesis: 2008 |journal=Current Opinion in Gastroenterology |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=36–43 |date=January 2009 |pmid=19114772 |pmc=2673536 |doi=10.1097/MOG.0b013e328317c897 |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0267-1379&volume=25&issue=1&spage=36}}</ref>。 |

|||

NSP5はA群ロタウイルスの第11分節にコードされる。感染細胞においてNSP5はヴィロプラズムに蓄積している<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Afrikanova I, Miozzo MC, Giambiagi S, Burrone O |title=Phosphorylation generates different forms of rotavirus NSP5 |journal=J. Gen. Virol. |volume=77 |pages=2059–65 |year=1996 |pmid=8811003 |url=http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/reprint/77/9/2059 |doi=10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2059 |issue=9}}</ref>。 |

|||

NSP6は核酸結合タンパク質で<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Rainsford EW, McCrae MA |title=Characterization of the NSP6 protein product of rotavirus gene 11 |journal=Virus Res. |volume=130 |issue=1–2 |pages=193–201 |year=2007 |pmid=17658646 |doi=10.1016/j.virusres.2007.06.011}}</ref>第11分節にコードされており、位相の異なる (out-of-phase) [[オープンリーディングフレーム]]から転写される<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Mohan KV, Atreya CD |title=Nucleotide sequence analysis of rotavirus gene 11 from two tissue culture-adapted ATCC strains, RRV and Wa |journal=Virus Genes |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=321–9 |year=2001 |pmid=11778700 |doi=10.1023/A:1012577407824}}</ref>。 |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" style="text-align:center" |

|||

|+ ロタウイルスの遺伝子とタンパク質 |

|||

! RNA分節 (遺伝子) !! 大きさ (塩基対) !! タンパク質 !! 分子量 [[Atomic mass unit|kDa]] !! 局在!!粒子あたりのコピー数 !!機能 |

|||

|- |

|||

! 1 |

|||

| 3302 || VP1 || 125 ||コアの頂点||<25 ||RNA依存性RNAポリメラーゼ |

|||

|- |

|||

! 2 |

|||

| 2690 || VP2 ||102||コアの内貼り||120 || RNA複製酵素の活性化 |

|||

|- |

|||

! 3 |

|||

| 2591 || VP3 ||88||コアの頂点||<25 || メチルトランスフェラーゼ、mRNAキャッピング酵素 |

|||

|- |

|||

! 4 |

|||

| 2362 || VP4 ||87||表面のスパイク||120 || 細胞への吸着、病原性 |

|||

|- |

|||

!5 |

|||

|1611||[[NSP1]]||59||非構造||0||5'RNAに結合、インターフェロン競合阻害 |

|||

|- |

|||

!6 |

|||

|1356||VP6||45||カプシドの内殻||780||構造タンパク質で種特異的抗原 |

|||

|- |

|||

!7 |

|||

|1104||[[NSP3]]||37||非構造||0||ウイルスmRNAの活性を増強し、細胞性のタンパク質合成を遮断 |

|||

|- |

|||

!8 |

|||

|1059||[[NSP2]]||35||非構造||0||RNAのパッケージングに関わるNTPase |

|||

|- |

|||

!9 |

|||

|1062||VP7<sup>1</sup> VP7<sup>2</sup>||38および34||表面||780||構造タンパク質、中和タンパク質 |

|||

|- |

|||

!10 |

|||

|751||[[NSP4]]||20||非構造||0 ||エンテロトキシン |

|||

|- |

|||

!11 |

|||

|667||[[NSP5]] [[NSP6]]||22||非構造||0|| ssRNAおよびdsRNAとの結合を担う、リン酸化を受ける |

|||

|} |

|||

この表はサルロタウイルスSA11株を許にしている<ref>Desselberger U. Rotavirus: basic facts. In ''Rotaviruses Methods and Protocols''. Ed. Gray, J. and Desselberger U. Humana Press, 2000, pp. 1–8. ISBN 0-89603-736-3</ref><ref>Patton JT. Rotavirus RNA replication and gene expression. In Novartis Foundation. ''Gastroenteritis Viruses'', Humana Press, 2001, pp. 64–81. ISBN 0-471-49663-4</ref><ref name="isbn0-12-249951-4">{{cite book |author1=Claude M. Fauquet |author2=J. Maniloff |author3=Desselberger, U. |title=Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses: 8th report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses |publisher=Elsevier/Academic Press |location=Amsterdam |year=2005 |pages= 489 |isbn=0-12-249951-4}}</ref>。RNAとタンパク質の割り当ては一部の株で異なる。 |

|||

===複製=== |

|||

[[Image:Rotavirus replication.png|thumb|ロタウイルスの複製過程|alt=A cartoon illustrating how a single rotavirus particle infects a cell, replicates in the cytoplasm and produces many progeny particles, which burst out from the host cell.]] |

|||

ロタウイルスの複製は主に腸で行われ<ref name="pmid19457420">{{cite journal |vauthors=Greenberg HB, Estes MK |title=Rotaviruses: from pathogenesis to vaccination |journal=Gastroenterology |volume=136 |issue=6 |pages=1939–51 |date=May 2009 |pmid=19457420 |doi=10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.076 |pmc=3690811 }}</ref>、[[小腸]]の腸細胞の[[絨毛]]に感染、[[上皮細胞|上皮]]に構造的、機能的変化をもたらす<ref name="pmid8050281">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Greenberg HB, Clark HF, Offit PA |title=Rotavirus pathology and pathophysiology |

|||

|journal=Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. |

|||

|volume=185 |

|||

|pages=255–83 |

|||

|year=1994 |

|||

|pmid=8050281 |

|||

}}</ref>。三重のタンパク質の被膜により胃の[[PH|酸性]]環境や腸管の消化酵素に耐えることができる。 |

|||

ロタウイルスは細胞へ受容体性エンドサイトーシスによって侵入、[[エンドソーム]]と呼ばれる小胞を形成する。最外層のタンパク質(VP7とVP4)はエンドソームの膜を破壊し、[[カルシウム]]濃度に変化をさせる。これがVP7三量体の崩壊を起こし、VP2とVP6によってなるdsRNAを包む殻を露出させた二重膜粒子の形成につながる<ref name="pmid20397068">{{cite journal |vauthors=Baker M, Prasad BV |title=Rotavirus cell entry |journal=Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology |volume=343|pages=121–48 |year=2010 |pmid=20397068 |doi=10.1007/82_2010_34 |series=Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology |isbn=978-3-642-13331-2}}</ref>。 |

|||

11の二本鎖RNA分節が二層のタンパク質の殻に囲まれたまま、ウイルス性の[[RNA依存性RNAポリメラーゼ]]によってウイルスのゲノムからmRNAが転写される。コアによって囲まれているため、ウイルスのRNAは、二本鎖RNAによって活性化する自然免疫反応である[[RNA干渉]]を回避することができる。 |

|||

感染時にロタウイルスはタンパク質の合成およびゲノム複製の両者のためにmRNAの合成を行う。ロタウイルスのタンパク質のほとんどはヴィロプラズムに集積し、RNAの複製と二重膜粒子の組み立てがこの場で行われる。ヴィロプラズムは核の周縁に感染後二時間で形成され始め、2つの非構造タンパク質、NSP5とNSP2によって構成されると考えられているウイルス工場である。RNA干渉によってNSP5を阻害するとロタウイルスの複製効率は急激に低下する。二重膜粒子は[[小胞体]]へ輸送され、VP7とVP4によって構成される三番目の殻、外膜を獲得する。娘ウイルスは細胞溶解を伴って放出される<ref name="pmid15010218" /><ref name="pmid15579070">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Patton JT, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Spencer E |title=Replication and transcription of the rotavirus genome |

|||

|journal=Curr. Pharm. Des. |

|||

|volume=10 |

|||

|issue=30 |

|||

|pages=3769–77 |

|||

|year=2004 |

|||

|pmid=15579070 |

|||

|doi=10.2174/1381612043382620 |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="pmid20024520">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ruiz MC, Leon T, Diaz Y, Michelangeli F |title=Molecular biology of rotavirus entry and replication |journal=TheScientificWorldJournal |volume=9|pages=1476–97 |year=2009 |pmid=20024520 |doi=10.1100/tsw.2009.158}}</ref>。 |

|||

==感染経路== |

|||

[[Image:Multiple rotavirus particles.jpg|right|thumb|Rotaviruses in the [[faeces]] of an infected child|alt=Many rotavirus particles packed together, which all look similar]] |

|||

ロタウイルスは汚染された手や物との接触を通じて[[糞口経路]]によって伝播するが<ref name="pmid8393172">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Butz AM, Fosarelli P, Dick J, Cusack T, Yolken R |title=Prevalence of rotavirus on high-risk fomites in day-care facilities |

|||

|journal=Pediatrics |

|||

|volume=92 |

|||

|issue=2 |

|||

|pages=202–5 |

|||

|year=1993 |

|||

|pmid=8393172 |

|||

}}</ref>、さらに空気感染の可能性もある<ref name="pmid11052397">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Dennehy PH |

|||

|title=Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home |

|||

|journal=Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. |

|||

|volume=19 |

|||

|issue=10 Suppl |

|||

|pages=S103–5 |

|||

|year=2000 |

|||

|pmid=11052397 |

|||

|doi=10.1097/00006454-200010001-00003 |

|||

}}</ref>。ウイルス性の下痢は感染性が非常に高い。感染者の糞便は1グラムあたりで最大10兆以上のウイルス粒子を含み<ref name="pmid9015109"/>、100以下のウイルス粒子でも感染が成立する<ref name="pmid18838873">{{cite journal |vauthors=Grimwood K, Lambert SB |title=Rotavirus vaccines: opportunities and challenges |journal=Human Vaccines |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=57–69 |date=February 2009 |pmid=18838873 |doi=10.4161/hv.5.2.6924 |url=http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/hv/abstract.php?id=6924}}</ref>。 |

|||

ロタウイルスは環境中でも安定である<ref name=NIID>{{Cite web|title=ロタウイルス感染性胃腸炎とは|url = http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/ja/kansennohanashi/3377-rota-intro.html|publisher= [[国立感染症研究所]]|accessdate=2017-02-02}}</ref>。<!--Rotaviruses are stable in the environment and have been found in [[estuary]] samples at levels up to 1–5 infectious particles per US gallon, the viruses survive between 9 and 19 days.<ref name="pmid6091548">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rao VC, Seidel KM, Goyal SM, Metcalf TG, Melnick JL |title=Isolation of enteroviruses from water, suspended solids, and sediments from Galveston Bay: survival of poliovirus and rotavirus adsorbed to sediments |journal=Appl. Environ. Microbiol. |volume=48 |issue=2 |pages=404–9 |date=1 August 1984|pmid=6091548 |url=http://aem.asm.org/cgi/reprint/48/2/404 |format=PDF |pmc=241526 }}</ref>-->[[真正細菌|細菌]]や[[寄生虫]]の除去に十分なほど衛生状態が良好でもロタウイルスの感染を抑えるには不十分なようであり、衛生状態の高い国と低い国でもロタウイルス感染症の罹患率はほとんど等しい<ref name="pmid11052397"/>。 |

|||

==発病機構== |

|||

[[Image:Rotavirus infected gut.jpg|thumb|ロタウイルスに感染した腸細胞(上)と非感染細胞(下)の電子顕微鏡像。スケールバー = 約500 nm|alt=The micrograph at the top shows a damaged cell with a destroyed surface. The micrograph at the bottom shows a healthy cell with its surface intact.]] |

|||

下痢はウイルスの活動によって発生する。[[吸収不良]]は[[腸細胞]](小腸吸収上皮細胞とも)と呼ばれる腸管の細胞の破壊による。ロタウイルスの産生するタンパク質、[[NSP4]]は[[エンテロトキシン]]であり、このタンパク質は年齢や[[カルシウム]]イオン依存的に塩化物イオンの分泌を促進、[[ナトリウム-グルコース共輸送タンパク質]]による水の再吸収を阻害、刷子縁の[[ジサッカリダーゼ]]を阻害する効果を持ち、さらに[[腸神経系]]のカルシウム依存性<!--(水?)-->分泌[[反射]]を活性化する可能性がある<ref name="pmid19114772">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hyser JM, Estes MK |title=Rotavirus vaccines and pathogenesis: 2008 |journal=Current Opinion in Gastroenterology |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=36–43 |date=January 2009 |pmid=19114772 |pmc=2673536 |doi=10.1097/MOG.0b013e328317c897 |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0267-1379&volume=25&issue=1&spage=36}}</ref>。腸細胞は小腸に[[ラクターゼ]]を分泌する役割を持ち、ラクターゼの喪失による牛乳不耐性はロタウイルス感染の症状の1つであるが<ref name="pmid18492865">{{cite journal |author=Farnworth ER |title=The evidence to support health claims for probiotics |journal=The Journal of Nutrition |volume=138 |issue=6 |pages=1250S–4S |date=June 2008 |pmid=18492865 |url=http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18492865}}</ref>、この症状は数週間に渡って継続する事がある<ref name="pmid12811680">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Ouwehand A, Vesterlund S |title=Health aspects of probiotics |

|||

|journal=IDrugs |

|||

|volume=6 |

|||

|issue=6 |

|||

|pages=573–80 |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

|pmid=12811680 |

|||

}}</ref>。牛乳をしばらく子どもの食事から除いた後、再び食事に加えるとしばしば軽度の下痢が再発する。これは腸管の細菌による[[二糖]]([[ラクトース]])の発酵が原因である<ref name="pmid6436397">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Arya SC |

|||

|title=Rotaviral infection and intestinal lactase level |

|||

|journal=J. Infect. Dis. |

|||

|volume=150 |

|||

|issue=5 |

|||

|page=791 |

|||

|year=1984 |

|||

|pmid=6436397 |

|||

|doi=10.1093/infdis/150.5.791 |

|||

}}</ref>。 |

|||

==診断と検出== |

|||

ロタウイルスの感染を診断するには通常重篤な下痢の原因となる[[胃腸炎]]の診断に続く。小児が胃腸炎によって病院で診察を受ける場合はほとんどの場合A群ロタウイルスの検査が行われる<ref name="pmid17901797">{{cite journal |vauthors=Patel MM, Tate JE, Selvarangan R, Daskalaki I, Jackson MA, Curns AT, Coffin S, Watson B, Hodinka R, Glass RI, Parashar UD |title=Routine laboratory testing data for surveillance of rotavirus hospitalizations to evaluate the impact of vaccination |journal=The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal |volume=26 |issue=10 |pages=914–9 |date=October 2007 |pmid=17901797 |doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52fd}}</ref><ref name="pmid16650331">{{cite journal |author=The Pediatric ROTavirus European CommitTee (PROTECT) |title=The paediatric burden of rotavirus disease in Europe |journal=Epidemiol. Infect. |volume=134 |issue=5 |pages=908–16 |year=2006 |pmid=16650331 |pmc=2870494 |doi=10.1017/S0950268806006091}}</ref>。A群ロタウイルスの特異的[[診断]]は小児の[[人糞|便]]を試料とした[[ELISA|ELISA法]]によるウイルスの検出によってなされる。感度、特異性が高い、A群ロタウイルスの全血清型を検出できる認可済みの診断キットは複数の製品が市場に流通している<ref name="isbn0-12-375147-0"/>。他の検出法としては、[[電子顕微鏡]]によるウイルス粒子の確認や、[[ポリメラーゼ連鎖反応|PCR]]による検出が研究目的の実験室で用いられる<ref name="isbn0-471-49663-4">{{cite book |author1=Goode, Jamie |author2=Chadwick, Derek |title=Gastroenteritis viruses |publisher=Wiley |location=New York |year=2001 |page=14 |isbn=0-471-49663-4}}</ref>。また、[[逆転写ポリメラーゼ連鎖反応|逆転写PCR]] (RT-PCR) 法を用いる事でヒトのロタウイルスの全ての種の全ての血清型を診断、同定できる<ref name="pmid15027000">{{cite journal |vauthors=Fischer TK, Gentsch JR |title=Rotavirus typing methods and algorithms |journal=Reviews in Medical Virology |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=71–82 |year=2004 |pmid=15027000 |doi=10.1002/rmv.411}}</ref>。 |

|||

==治療と予後== |

|||

ロタウイルスの急性感染における治療は非特異的な対症療法であり、脱水の対策が最も重要となる<ref name="pmid18026034">{{cite journal|author=Diggle L|title=Rotavirus diarrhea and future prospects for prevention|journal=Br. J. Nurs.|volume=16|issue=16|pages=970–4|year=2007|pmid=18026034}}</ref>。無治療の場合、小児は重度の脱水を起こすと死に至る事もある<ref name="pmid12608880">{{cite journal|vauthors=Alam NH, Ashraf H |title=Treatment of infectious diarrhea in children|journal=Paediatr. Drugs|volume=5|issue=3|pages=151–65|year=2003|pmid=12608880|doi=10.2165/00128072-200305030-00002}}</ref>。下痢の重篤度に応じて経口補液を行い、補液時においては少量の塩分と糖分を含む十分な量の水を飲ませる<ref name="pmid8855579">{{cite journal |author=Sachdev HP |title=Oral rehydration therapy |journal=Journal of the Indian Medical Association |volume=94 |issue=8 |pages=298–305 |year=1996 |pmid=8855579}}</ref>。2004年にはWHOとUNICEFが急性下痢の治療用に低浸透圧の[[経口補水液]]と亜鉛サプリメントの併用を推奨している<ref name="WHO UNICEF">{{cite web|last=World Health Organization, UNICEF|title=Joint Statement: Clinical Management of Acute Diarrhoea|url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_FCH_CAH_04.7.pdf|accessdate=3 May 2012}}</ref>。感染した小児のおよそ50%が受診、そのうち約10%が脱水を理由に入院が必要となり<ref name="stmicrobiol">{{Cite book|和書|editor=平松啓一・中込治|title=標準微生物学|edition=第10版|year=2009|publisher=医学書院|page=426-434|isbn=978-4-260-00638-5}}</ref>、[[点滴静脈注射|点滴]]や[[経鼻胃管]]による補液、[[電解質]]や[[血糖値]]のモニタリングが行われる<ref name="pmid17901797">{{cite journal |vauthors=Patel MM, Tate JE, Selvarangan R, Daskalaki I, Jackson MA, Curns AT, Coffin S, Watson B, Hodinka R, Glass RI, Parashar UD |title=Routine laboratory testing data for surveillance of rotavirus hospitalizations to evaluate the impact of vaccination |journal=The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal |volume=26 |issue=10 |pages=914–9 |date=October 2007 |pmid=17901797 |doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52fd}}</ref>。また、[[プロバイオティクス]]はロタウイルスによる下痢の持続期間を減少させることが示されており<ref name="pmid26644891">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ahmadi E, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Rezai MS |title=Efficacy of probiotic use in acute rotavirus diarrhea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=Caspian J Intern Med |volume=6 |issue=4 |pages=187–95 |date=2015}}</ref>、ヨーロッパ小児消化器病学会は「効果的な介入として[[ラクトバチルス・ラムノサス]]や[[サッカロマイセス・ブラウディ]]などのプロバイオティクス、[[ジオスメクタイト]]、[[ラセカドトリル]]の投与がある<ref name="pmid24739189">{{cite journal |author=Guarino A1, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, Lo Vecchio A, Shamir R, Szajewska H |title=European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: update 2014. |journal=J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=132–52 |date=2014 |doi=10.1097/mpg.0000000000000375}}</ref>」としている。ロタウイルスが他の合併症を招く事は稀であり、先進国では適切に治療されれば小児の予後は良好であるが<ref name="pmid17678424">{{cite journal |author=Ramig RF |title=Systemic rotavirus infection |journal=Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy |volume=5 |issue=4 |pages=591–612 |date=August 2007 |pmid=17678424 |doi=10.1586/14787210.5.4.591}}</ref>、発展途上国では年間数十万人がロタウイルス感染による下痢症で死亡し<ref name="stmicrobiol"/>、また、腸重積、肝炎、胆道閉鎖症、1型糖尿病、腎後性腎不全、[[脳炎]]、[[髄膜炎]]、[[脳症]]などさまざまな病態との関連が疑われる事もある<ref name=NIID/><ref name="stmicrobiol"/><ref>[http://dx.doi.org/10.4264/numa.67.304 ロタウイルス感染に関連した急性脳症の 1例] 日大医学雑誌 Vol.67 (2008) No.5 P304-308</ref>。 |

|||

==疫学== |

|||

[[Image:Rotavirus seasonal distribution.png|left|thumb|イングランドのある地域におけるA群ロタウイルス感染の季節変動。冬期に感染者数がピークとなる。|alt=A line graph with the months and years on the x-axis and the number of infections on the y-axis. The peaks in the line correspond to the winter months of the northern hemisphere.]] |

|||

A群ロタウイルスはヒトのロタウイルス性胃腸炎の原因の90%を占め、世界的に常在している<ref name="pmid16418157">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Leung AK, Kellner JD, Davies HD |title=Rotavirus gastroenteritis |

|||

|journal=Adv. Ther. |

|||

|volume=22 |

|||

|issue=5 |

|||

|pages=476–87 |

|||

|year=2005 |

|||

|pmid=16418157 |

|||

|doi=10.1007/BF02849868 |

|||

}}</ref>。発展途上国では一年間にロタウイルスが数百万件の下痢症を引き起こしており、このうちのほぼ200万件の患者が入院する<ref name="pmid17919334">{{cite journal|year=2007|title=Use of formative research in developing a knowledge translation approach to rotavirus vaccine introduction in developing countries|url=http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/7/281|journal=BMC Public Health|volume=7|issue=|page=281|doi=10.1186/1471-2458-7-281|pmc=2173895|pmid=17919334|vauthors=Simpson E, Wittet S, Bonilla J, Gamazina K, Cooley L, Winkler JL}}</ref>。2013年には5歳未満の幼児、215,000人がロタウイルスにより死亡しており、その90%は発展途上国における死である<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Tate|first=Jacqueline E.|last2=Burton|first2=Anthony H.|last3=Boschi-Pinto|first3=Cynthia|last4=Parashar|first4=Umesh D.|date=2016|title=Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000–2013|url=http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/62/suppl_2/S96.full|journal=Clinical Infectious Diseases|volume=62|issue=Suppl 2|pages=S96-S105|doi=|pmid=|access-date=|via=}}</ref>。5歳までにほぼ全ての幼児がロタウイルスに感染する<ref name="pmid16494759">{{cite journal |

|||

|vauthors=Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, Glass RI |title=Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea |

|||

|journal=Emerging Infect. Dis. |

|||

|volume=12 |

|||

|issue=2 |

|||

|pages=304–6 |

|||

|year=2006 |

|||

|pmid=16494759 |

|||

|doi=10.3201/eid1202.050006 |

|||

|pmc=3373114 |

|||

}}</ref>。ロタウイルスは乳幼児の重篤な下痢の主因であり、入院の原因の3分の1を占め<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Leshem|first=Eyal|last2=Moritz|first2=Rebecca E.|last3=Curns|first3=Aaron T.|last4=et al.|date=2014|title=Rotavirus Vaccines and Health Care Utilization for Diarrhea in the United States (2007–2011)|url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/1/15|journal=Pediatrics|volume=134|issue=1|pages=15–23|doi=|pmid=|access-date=|via=}}</ref>、5歳未満の乳幼児において下痢に起因する死の37%、全死因の5%をそれぞれ占める<ref name="pmid22030330">{{cite journal|date=February 2012|title=2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis|journal=Lancet Infect Dis|volume=12|issue=2|pages=136–141|doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5|pmid=22030330|vauthors=Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD}}</ref>。男児は女児に比べ、ロタウイルスにより入院する事が多いようである<ref name="pmid16397429">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rheingans RD, Heylen J, Giaquinto C |title=Economics of rotavirus gastroenteritis and vaccination in Europe: what makes sense? |journal=Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. |volume=25 |issue=1 Suppl |pages=S48–55 |year=2006 |pmid=16397429 |doi=10.1097/01.inf.0000197566.47750.3d}}</ref><ref name="pmid8752285">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ryan MJ, Ramsay M, Brown D, Gay NJ, Farrington CP, Wall PG |title=Hospital admissions attributable to rotavirus infection in England and Wales |journal=J. Infect. Dis. |volume=174 |issue=Suppl 1 |pages=S12–8 |year=1996 |pmid=8752285 |doi=10.1093/infdis/174.Supplement_1.S12}}</ref>。 |

|||

ロタウイルスの感染は主に冷涼で乾燥した季節に発生する<ref name="pmid19939844">{{cite journal |vauthors=Atchison CJ, Tam CC, Hajat S, van Pelt W, Cowden JM, Lopman BA |title=Temperature-dependent transmission of rotavirus in Great Britain and The Netherlands |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=277 |issue=1683 |pages=933–42 |date=March 2010 |pmid=19939844 |pmc=2842727 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2009.1755 |url=http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19939844}}</ref><ref name="pmid19056806">{{cite journal |vauthors=Levy K, Hubbard AE, Eisenberg JN |title=Seasonality of rotavirus disease in the tropics: a systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=International Journal of Epidemiology |volume=38 |issue=6 |pages=1487–96 |date=December 2009 |pmid=19056806 |pmc=2800782 |doi=10.1093/ije/dyn260 |url=http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19056806}}</ref>。汚染食料に起因する感染事例数は定かでない<ref name="pmid10088906">{{cite journal |vauthors=Koopmans M, Brown D |title=Seasonality and diversity of Group A rotaviruses in Europe |journal=Acta Paediatrica Supplement |volume=88 |issue=426 |pages=14–9 |year=1999 |pmid=10088906 |doi=10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14320.x}}</ref>。 |

|||

A群ロタウイルスによる下痢症は病院にいる乳児、デイケアセンターを利用する幼児、老人ホームに住む高齢者等の間で流行する<ref name="pmid14871633">{{cite journal |vauthors=Anderson EJ, Weber SG |title=Rotavirus infection in adults |journal=The Lancet Infectious Diseases |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=91–9 |date=February 2004 |pmid=14871633 |doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00928-4 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309904009284}}</ref>。また、コロラドでは1981年に汚染された水道水が原因になって流行したこともある<ref name="pmid6320684">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hopkins RS, Gaspard GB, Williams FP, Karlin RJ, Cukor G, Blacklow NR |title=A community waterborne gastroenteritis outbreak: evidence for rotavirus as the agent |journal=American Journal of Public Health |volume=74 |issue=3 |pages=263–5 |year=1984 |pmid=6320684 |pmc=1651463 |doi=10.2105/AJPH.74.3.263}}</ref>。 |

|||

2005年にはニカラグアで記録に残る上では最大級の流行が発生した。この前例のない大規模な流行はA群ロタウイルスのゲノムに生じた変異と関連しており、ウイルスは変異を起こす事で住民の間で共有されていた免疫を回避する事ができた可能性がある<ref name="pmid17229854">{{cite journal |vauthors=Bucardo F, Karlsson B, Nordgren J, etal |title=Mutated G4P[8] rotavirus associated with a nationwide outbreak of gastroenteritis in Nicaragua in 2005 |journal=J. Clin. Microbiol. |volume=45 |issue=3 |pages=990–7 |year=2007 |pmid=17229854 |doi=10.1128/JCM.01992-06 |url=http://jcm.asm.org/cgi/content/full/45/3/990 |pmc=1829148}}</ref>。同等の大流行は1977年にブラジルでも発生している<ref name="pmid6263087">{{cite journal |vauthors=Linhares AC, Pinheiro FP, Freitas RB, Gabbay YB, Shirley JA, Beards GM |title=An outbreak of rotavirus diarrhea among a non-immune, isolated South American Indian community |journal=Am. J. Epidemiol. |volume=113 |issue=6 |pages=703–10 |year=1981 |pmid=6263087}}</ref>。 |

|||

成人下痢症ウイルス(ADRV株)とも呼ばれるB群ロタウイルスは中国で感染者が全世代に渡る、数千人規模の大流行を起こしてきた。この一連の流行は飲料用の水が下水によって汚染されたために発生している<ref name="pmid6144874">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hung T, Chen GM, Wang CG, etal |title=Waterborne outbreak of rotavirus diarrhea in adults in China caused by a novel rotavirus |journal=Lancet |volume=1 |issue=8387 |pages=1139–42 |year=1984 |pmid=6144874 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91391-6}}</ref><ref name="pmid2555422">{{cite journal |vauthors=Fang ZY, Ye Q, Ho MS, etal |title=Investigation of an outbreak of adult diarrhea rotavirus in China |journal=J. Infect. Dis. |volume=160 |issue=6 |pages=948–53 |year=1989 |pmid=2555422 |doi=10.1093/infdis/160.6.948}}</ref>。1998年にはインドでもB群ロタウイルス感染症が発生しており、病原ウイルスの株名がCAL株と命名された。流行を起こしてきたADRV株と異なり、CAL株は常在性であるようである<!--地方病性の方がいいかもしれないが要出典確認--><ref name="pmid15310177">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kelkar SD, Zade JK |title=Group B rotaviruses similar to strain CAL-1, have been circulating in Western India since 1993 |journal=Epidemiol. Infect. |volume=132 |issue=4 |pages=745–9 |year=2004 |pmid=15310177 |pmc=2870156 |doi=10.1017/S0950268804002171}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Ahmed MU, Kobayashi N, Wakuda M, Sanekata T, Taniguchi K, Kader A, Naik TN, Ishino M, Alam MM, Kojima K, Mise K, Sumi A |title=Genetic analysis of group B human rotaviruses detected in Bangladesh in 2000 and 2001 |journal=J. Med. Virol. |volume=72 |issue=1 |pages=149–55 |year=2004 |pmid=14635024 |doi=10.1002/jmv.10546}}</ref>。これまでのB群ロタウイルスの流行は特定の地域に限局にしており、例えばアメリカ人はB群ロタウイルスに対して免疫を持たないことが血清調査から示されている<ref name="pmid2479654">{{cite journal |vauthors=Penaranda ME, Ho MS, Fang ZY, etal |title=Seroepidemiology of adult diarrhea rotavirus in China, 1977 to 1987 |journal=J. Clin. Microbiol. |volume=27 |issue=10 |pages=2180–3 |date=1 October 1989|pmid=2479654 |url=http://jcm.asm.org/cgi/reprint/27/10/2180 |format=PDF |pmc=266989}}</ref>。 |

|||

C群ロタウイルスは散発的に小児の下痢を引き起こしており、小規模の流行が家庭内で生じた事もある<ref>{{cite book |author=Desselberger U, Iturriza-Gomera, Gray JJ|title=Gastroenteritis viruses |publisher=Wiley |location=New York |year=2001 |pages=127–128 |isbn=0-471-49663-4}}</ref>。 |

|||

== 予防 == |

== 予防 == |

||

{{main article|ロタウイルスワクチン}} |

|||

手洗い、充分な加熱。吐物・糞便の始末の後、適切な消毒を要する。アルコールは無効なため、次亜塩素酸ナトリウム液などで消毒すべきである。[[ノロウイルス]]ほど感染力は強くはないが、ほぼ同様の予防策を講じるべきであろう。 |

|||

ロタウイルスは感染性が強く、また抗生物質やその他の治療薬は効果がない。衛生状態の改善ではロタウイルス感染症の蔓延を防ぐことができず、一方で経口補水を行なってもなお入院率が高いため、ロタウイルスへの主な医療介入には予防接種が行われる<ref name="pmid19252423">{{cite journal |author=Bernstein DI |title=Rotavirus overview |journal=The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal |volume=28 |issue=3 Suppl |pages=S50–3 |date=March 2009 |pmid=19252423 |doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967bee |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0891-3668&volume=28&issue=3&spage=S50}}</ref>。世界的に認可されているA群ロタウイルスに対してのワクチンとして、ロタリックス(Rotarix; [[グラクソ・スミスクライン]])<ref>{{cite journal |author=O'Ryan M |title=Rotarix (RIX4414): an oral human rotavirus vaccine |journal=Expert review of vaccines |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=11–9 |year=2007 |pmid=17280473 |doi=10.1586/14760584.6.1.11}}</ref>およびロタテック (RotaTeq; [[メルク・アンド・カンパニー|MSD]]) <ref name="pmid17055370">{{cite journal |author=Matson DO |title=The pentavalent rotavirus vaccine, RotaTeq |journal=Seminars in paediatric infectious diseases |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=195–9 |year=2006 |pmid=17055370 |doi=10.1053/j.spid.2006.08.005}}</ref>が存在し、いずれも小児に対して安全で効果的である<ref name="pmid20622508">{{cite journal |vauthors=Jiang V, Jiang B, Tate J, Parashar UD, Patel MM |title=Performance of rotavirus vaccines in developed and developing countries |journal=Human Vaccines |volume=6 |issue=7 |pages=532–42 |date=July 2010 |pmid=20622508 |doi=10.4161/hv.6.7.11278 |url=http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/hv/abstract.php?id=11278 |pmc=3322519}}</ref>。重症ロタウイルス下痢症乳児の大幅な減少成果を認め<ref>[http://dx.doi.org/10.2222/jsv.62.87 谷口 孝喜:ヒトロタウイルスワクチン] ウイルス Vol.62 (2012) No.1 p.87-96</ref>、共に[[コクラン共同計画|コクラン]]のレビューで発症阻止能が認められている<ref name="CD008521">{{cite journal |author=Soares-Weiser K, Maclehose H, Bergman H, ''et al.'' |editor1-last=Soares-Weiser |editor1-first=Karla |title=Vaccines for preventing rotavirus diarrhoea: vaccines in use |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=11 |issue= |pages=CD008521 |year=2012 |pmid=23152260 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008521.pub3}}</ref>。1990年代に使用されていたワクチン (RotaShield) の副反応として腸重積が多発したことが報告されていたが<ref name="moden_m" />、2006年頃以降市場に出ているワクチンと腸重積との関連性は認められていない。いずれも経口ワクチンで弱毒生ウイルスを含む<ref name="pmid20622508" />。2014年にインドで認可されたROTAVAC、2007年にベトナムで認可されたMotavin-M1、2000年に中国で認可されたLanzhou Lambの3つは特定の国の市場においてのみ認可されている<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://rotacouncil.org/resources/White-paper-FINAL-v2.pdf|title=Rotavirus: Common, Severe, Devastating, Preventable|last=Rota Council|first=|publisher=|year=2016|isbn=|location=|pages=|via=}}</ref>。2017年現在、二つの有効なワクチンの保存は冷蔵できる環境が必要である。このことは、コストが大きくなるとともに接種可能な場所や対象は制約を受ける。このため、新たなワクチンの開発も試みられている<ref>[http://www.afpbb.com/articles/-/3122457 ロタウイルス最新ワクチンに高い有効性、アフリカの子どもに希望の光] AFP(2017年3月23日)2017年3月27日閲覧</ref>。また、他にも複数のロタウイルスワクチンが開発中である<ref name="pmid20684721">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ward RL, Clark HF, Offit PA |title=Influence of potential protective mechanisms on the development of live rotavirus vaccines |journal=The Journal of Infectious Diseases |volume=202 |issue=Suppl |pages=S72–9 |date=September 2010 |pmid=20684721 |doi=10.1086/653549 |url=http://www.jid.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20684721}}</ref>。 |

|||

2009年に[[世界保健機関|世界保健機構]](WHO)は各国における予防接種プログラムへのロタウイルスワクチン導入を推奨した<ref name="pmid20370550">{{cite journal |vauthors=Tate JE, Patel MM, Steele AD, Gentsch JR, Payne DC, Cortese MM, Nakagomi O, Cunliffe NA, Jiang B, Neuzil KM, de Oliveira LH, Glass RI, Parashar UD |title=Global impact of rotavirus vaccines |journal=Expert Review of Vaccines |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=395–407 |date=April 2010 |pmid=20370550 |doi=10.1586/erv.10.17}}</ref>。この推奨策を実施した国ではロタウイルス感染症の発生率と重症度が明らかに減衰している<ref name="pmid21734466">{{cite journal |vauthors=Giaquinto C, Dominiak-Felden G, Van Damme P, Myint TT, Maldonado YA, Spoulou V, Mast TC, Staat MA |title=Summary of effectiveness and impact of rotavirus vaccination with the oral pentavalent rotavirus vaccine: a systematic review of the experience in industrialized countries |journal=Human Vaccines |volume=7 |issue=7 |pages=734–48 |date=July 2011 |pmid=21734466 |doi=10.4161/hv.7.7.15511 |url=http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/hv/abstract.php?id=15511}}</ref><ref name="pmid20622508" /><ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|first=|date=2016|editor-last=Parashar|editor-first=Umesh D.|editor2-last=Tate|editor2-first=Jacqueline E.|title=Health Benefits of Rotavirus Vaccination in Developing Countries|url=http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/62/suppl_2.toc|journal=Clinical Infectious Diseases|volume=62|issue=Suppl 2|pages=S91-S228|doi=|pmid=|access-date=|via=}}</ref>。予防接種プログラムにロタウイルスワクチンを導入した国において行われた臨床治験のデータをまとめた2014年のレビューはロタウイルスワクチンがロタウイルスに起因する入院を49-92%減少させ、さらに全下痢症の入院患者数を17-55%減少させることを明らかにした<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Tate|first=Jacqueline E.|last2=Parashar|first2=Umesh D.|date=2014|title=Rotavirus Vaccines in Routine Use|url=http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/59/9/1291|journal=Clinical Infectious Diseases|volume=59|issue=9|pages=1291–1301|doi=|pmid=|access-date=|via=}}</ref>。 2006年にロタウイルスワクチンを世界で初めて導入した国の1つであるメキシコでは、ロタウイルス性の下痢症による2歳以下の死亡率が2009年のシーズンには65%以上減少した<ref>{{cite journal|last=Richardson|first=V|author2=Hernandez-Pichardo J |author3=Quintanar-Solares M |author4=et al. |title=Effect of Rotavirus Vaccination on Death From Childhood Diarrhea in Mexico|journal=The New England Journal of Medicine|year=2010|volume=362|issue=4|pages=299–305|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0905211|pmid=20107215|displayauthors=2}}</ref>。ニカラグアは2006年に発展途上国として初めてロタウイルスワクチンを導入し、ロタウイルスの感染を40%まで減少させ、救急救命室の利用を半減させた<ref name="pmid22753550">{{cite journal |vauthors=Patel M, Pedreira C, De Oliveira LH, etal |title=Duration of protection of pentavalent rotavirus vaccination in Nicaragua |journal=Pediatrics |volume=130 |issue=2 |pages=e365–72 |date=August 2012 |pmid=22753550 |doi=10.1542/peds.2011-3478}}</ref>。アメリカ合衆国ではロタウイルスワクチンの接種が2006年に開始され、ロタウイルスの検出数が86%低下している<ref>{{cite journal|authors=Tate JE, Mutuc JD, Panozzo CA, Payne DC, Cortese MM, Cortes JE, Yen C, Esposito DH, Lopman BA, Patel MM, Parashar UD|title=Sustained decline in rotavirus detections in the United States following the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in 2006.|journal=Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal|date=January 2011|volume=30|issue=1 Supplement|accessdate=10 Apr 2017|doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ffe3eb.|pages=S30-4|pmid=21183838}}</ref>。ワクチンは市中の感染数を減少させることで、免疫を受けていない小児の疾患をも予防するかもしれない<ref>{{cite journal|authors=Patel MM, Parashar UD, eds.|title=Real World Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination|journal=Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal|date=January 2011|volume=30|issue=Supplement|url=http://journals.lww.com/pidj/toc/2011/01001|accessdate=8 May 2012|doi=10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefa1f|pages=S1|pmid=21183833}}</ref>。ロタウイルスによる死はほとんどがアフリカやアジアの発展途上国で発生するが、これらの国々ではRotarixとRotaTeqに関する多数の臨床試験が行われた他、近年はワクチン導入後の影響を評価する調査が実施され、ワクチンの導入によって乳児の重症例が劇的に減少することが示された<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=2010|editor-last=Steele|editor-first=A. Duncan|editor2-last=Armah|editor2-first=George E.|editor3-last=Page|editor3-first=Nicola A.|editor4-last=Cunliffe|editor4-first=Nigel A.|title=Rotavirus Infection in Africa: Epidemiology, Burden of Disease, and Strain Diversity|url=http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/202/Supplement_1.toc|journal=Journal of Infectious Diseases|volume=202|issue=Suppl 1|pages=S1-S265|doi=|pmid=|access-date=|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=2009|editor-last=Nelson|editor-first=E. Anthony S.|editor2-last=Widdowson|editor2-first=Marc-Alain|editor3-last=Kilgore|editor3-first=Paul E.|editor4-last=Steele|editor4-first=Duncan|editor5-last=Parashar|editor5-first=Umesh D.|title=Rotavirus in Asia: Updates on Disease Burden, Genotypes and Vaccine Introduction|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/0264410X/27/supp/S5|journal=Vaccine|volume=27|issue=Suppl 5|pages=F1-F138|doi=|pmid=|access-date=|via=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=World Health Organization|title=Rotavirus vaccines: an update|journal=Weekly Epidemiological Record|date=December 2009|volume=51–52|issue=84|pages=533–540|url=http://www.who.int/wer/2009/wer8451_52.pdf|accessdate=8 May 2012}}</ref>。2013年にはイギリスで2-3ヶ月の全ての乳児に対しワクチンが提供された。これはロタウイルス感染の重症例を半減させ、入院例を70%減少させることを期待して行われている<ref>[http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/11/rotavirus/ UK Department of Health: New vaccine to help protect babies against rotavirus. Retrieved on 10 November, 2012]</ref>。ヨーロッパではワクチンの導入によってロタウイルス感染による入院例が65%から84%減少した<ref name="pmid25795258">{{cite journal |vauthors=Karafillakis E, Hassounah S, Atchison C |title=Effectiveness and impact of rotavirus vaccines in Europe, 2006-2014 |journal=Vaccine |volume=33 |issue=18 |pages=2097–107 |year=2015 |pmid=25795258 |doi=10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.016 |url=}}</ref>。 |

|||

ワクチンとして、ロタリックス(Rotarix; [[グラクソ・スミスクライン]])およびロタテック (RotaTeq; [[メルク・アンド・カンパニー|MSD]]) が存在し、重症ロタウイルス下痢症乳児の大幅な減少成果を認め<ref>[http://dx.doi.org/10.2222/jsv.62.87 谷口 孝喜:ヒトロタウイルスワクチン] ウイルス Vol.62 (2012) No.1 p.87-96</ref>、共に[[コクラン共同計画|コクラン]]のレビューで発症阻止能が認められている<ref name="CD008521">{{cite journal |author=Soares-Weiser K, Maclehose H, Bergman H, ''et al.'' |editor1-last=Soares-Weiser |editor1-first=Karla |title=Vaccines for preventing rotavirus diarrhoea: vaccines in use |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=11 |issue= |pages=CD008521 |year=2012 |pmid=23152260 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008521.pub3}}</ref>。1990年代に使用されていたワクチン (RotaShield) の副反応として腸重積が多発したことが報告されていたが<ref name="moden_m"/>、2006年頃以降市場に出ているワクチンと腸重積との関連性は認められていない。しかし、腸重積の既往のある子どもの場合、再発することがあるので、注意は必要である。ワクチンは生後2, 4, 6ヶ月に経口接種となる。生後6週から接種可能で、接種間隔は4~8週。3回目の接種を生後8ヶ月までに完了させる。ロタウイルス・ワクチン接種前後の接触制限はない。 |

|||

ロタウイルスワクチンは100カ国以上の国で認可されており、さらに80カ国以上の国が予防接種プログラムに組み入れている。また、そのうちおよそ半数の国は[[GAVIアライアンス]]による援助を受けている<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://rotacouncil.org/toolkit/rotavirus-burden-vaccine-introduction-map/|title=Rotavirus Deaths & Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction Maps – ROTA Council|website=rotacouncil.org|access-date=2016-07-29}}</ref>。ロタウイルスワクチンを全ての国(特にロタウイルスによる死のほとんどが発生するアフリカやアジアの低所得ないし中所得国)に導入させるため、PATH、WHO、[[アメリカ疾病予防管理センター]]および[[GAVIアライアンス]]は研究機関や政府と協力し、普及活動に努めている<ref name="pmid21957215">{{cite journal |author=Moszynski P |title=GAVI rolls out vaccines against child killers to more countries |journal=BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) |volume=343 |pages=d6217 |year=2011 |pmid=21957215 |doi=10.1136/bmj.d6217 |url=http://www.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21957215}}</ref>。 |

|||

==動物のロタウイルス感染== |

|||

== 関連 == |

|||

ロタウイルスは多くの種の動物の幼齢個体に感染し、野生動物にとっても飼育動物にとってもロタウイルスは世界的に下痢の主要な病原体である<ref name="isbn0-12-375158-6">{{cite book |author1=Edward J Dubovi |author2=Nigel James MacLachlan |title=Fenner's Veterinary Virology, Fourth Edition |publisher=Academic Press |location=Boston |year=2010 |page=288 |isbn=0-12-375158-6}}</ref>。仔牛や仔豚をはじめとした家畜の病原体として、高い罹患率と致死率を持つロタウイルスは治療に係る経費によって農場経営者に対し経済的損失を生じさせる<ref name="pmid19781872">{{cite journal |vauthors=Martella V, Bányai K, Matthijnssens J, Buonavoglia C, Ciarlet M |title=Zoonotic aspects of rotaviruses |journal=Veterinary Microbiology |volume=140 |issue=3–4 |pages=246–55 |date=January 2010 |pmid=19781872 |doi=10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.028}}</ref>。また、動物のロタウイルスはヒトのロタウイルスと遺伝子を交換することができる<ref name="pmid19781872" />。動物のロタウイルスがヒトに感染することがあり、これは直接動物のウイルスがヒトに感染する場合と、動物のロタウイルスのRNA分節の一部が[[遺伝子再集合]]を経てヒトの株に取り込まれる場合とがある<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Müller H, Johne R |title=Rotaviruses: diversity and zoonotic potential—a brief review |journal=Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. |volume=120 |issue=3–4 |pages=108–12 |year=2007 |pmid=17416132}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Cook N, Bridger J, Kendall K, Gomara MI, El-Attar L, Gray J |title=The zoonotic potential of rotavirus |journal=J. Infect. |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=289–302 |year=2004 |pmid=15066329 |doi=10.1016/j.jinf.2004.01.018}}</ref>。 |

|||

* [[感染症]] |

|||

== 脚注 == |

== 脚注 == |

||

2017年7月16日 (日) 15:32時点における版

| ロタウイルス | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

電子顕微鏡によるロタウイルス(スケールバー100nm)

| ||||||||||||

| 分類 | ||||||||||||

|

ロタウイルス (Rotavirus) は、レオウイルス科の一種のウイルス。1973年に見つかった。2層のタンパク質の殻に覆われた2本鎖RNA (double-strand RNA) ウイルス。

一般に乳児下痢症・嘔吐下痢症の原因としても知られている。アメリカ合衆国では年間50万人以上が主に下痢症状で受診し、特に小児は重篤な下痢を起こし易く、罹患患者の10%は入院となる。地域差があると考えられるが世界で毎年約70万人程度が亡くなっていると考えられている[1]。

徴候と症状

ロタウイルス性腸炎は軽度から重度の至る疾患で、吐き気、嘔吐、水様性の下痢、軽い発熱を特徴とする。幼児がロタウイルスに感染した場合、症状が現れるまでの潜伏期 (incubation period) は約2日程度である[2]。腸炎は急性経過をとり、発症後しばしば最初に嘔吐が認められ、その後4日から8日程度の重篤な下痢が続く。脱水症状が他の細菌性下痢症に比べ発生しやすく、これはロタウイルス感染症の主要な死因でもある[3]。

A群ロタウイルスの感染は生涯を通じて起こりうるが、初感染時に通常認められる症状は、2回目以降では軽微、あるいは不顕性である[4][5]。2回目以降の感染時の症状の減弱は免疫系による防御に由来する引用エラー: <ref> タグ内の引数が無効です[6]。そのため顕性感染は2歳以下の乳幼児で多く、45歳まで年齢を重ねるにつれて減少する引用エラー: <ref> タグ内の引数が無効です。新生児の感染はよくみられるが、軽微か不顕性である事が比較的多く[7]、最も重症化しやすいのは6ヶ月から10歳の乳幼児・小児や高齢者、あるいは免疫不全症患者である。幼少期に獲得する免疫により、ほとんどの成人はロタウイルスに抵抗性である。成人の胃腸炎は通常他の病原体によるが、一方で成人の不顕性感染が集団における感染経路の維持に寄与している可能性がある[8]。

ウイルス学

ロタウイルスの型

ロタウイルスはAからH群までの8つの種に分かれる[9]。ヒトは主にA群、B群、C群に感染し、特にA群への感染が一般的である[10]。E群やH群はブタに、D群、E群、F群は鳥類に感染する[11][12]。A群ロタウイルスはさらに複数の株に分かれ、これを血清型と呼ぶ[13]。血清型はインフルエンザウイルスと同様に2つの表面タンパク質の組み合わせによって命名される。糖タンパク質VP7がG血清型を、プロテアーゼ感受性タンパク質VP4がP血清型を決定する[14]。G型を定義する遺伝子とP型を定義する遺伝子は別々に子孫ウイルスへ継がれるため、様々な組み合わせが生じる[15]。

構造

ロタウイルスのゲノムは11分節に分かれる計18,555塩基対の二本鎖RNAである。各分節は一つの遺伝子であり、大きいものから順に1から11の番号が割り当てられている。各遺伝子は1種類のタンパク質をコードしているが、第9遺伝子分節は例外的に2つのタンパク質をコードする[16]。RNAは外殻、内殻からなる二層のカプシドと、その内層に存在するコアの合わせて三層からなるタンパク質に包まれ[17]、コアを包むカプシドタンパク質の形状は正二十面体である。ウイルス粒子の粒子径は最大で76.4 nmであり[18][19]、エンベロープを持たない。

タンパク質

6つのウイルスタンパク質 (VP) がウイルスの粒子を構成する。この構造タンパク質群はそれぞれVP1、VP2、VP3、VP4、VP6およびVP7と呼ばれる。構造タンパク質であるVPに加え、ロタウイルスは感染細胞の細胞内ではさらに非構造タンパク質 (NSP) を合成する。この非構造タンパク質はそれぞれNSP1、NSP2、NSP3、NSP4、NSP6およびNSP7と呼ばれる[20]。

ロタウイルスゲノムにコードされる12の遺伝子のうち、6つはRNA結合性タンパク質である[21]。ロタウイルスの複製におけるこれらのタンパク質の役割は完全には理解されていないが、RNAの合成とウイルス粒子へのパッケージング、ゲノム複製の場へのmRNA輸送、mRNAの翻訳と遺伝子発現調節に関与すると考えられている[22]。

構造タンパク質

VP1はウイルス粒子のコア内に存在するRNAポリメラーゼである[23]。感染細胞内でVP1はウイルスタンパク質の合成や新しく合成されたウイルス粒子のゲノムとなるRNA分節の複製に用いられるmRNAを合成する。

VP2はウイルス粒子のコアを形成し、RNAと結合する[24]。

VP3はコアの成分の1つで、グアニリルトランスフェラーゼと呼ばれる酵素である。VP3はキャップ形成酵素であり、mRNAの転写後修飾として生じる5'キャップの付加反応を触媒する[25]。キャップ構造は核酸を分解する酵素であるヌクレアーゼからウイルスmRNAを保護することで、mRNAの安定化に寄与する[26]。

VP4はスパイク状の突起としてウイルス粒子の表面に存在する外殻タンパク質である[17][27]。VP4は細胞表面の受容体と呼ばれる分子に結合し、ウイルスの細胞への侵入を引き起こす[28]。VP4は腸管に発現しているプロテアーゼであるトリプシンによって処理を受け、VP5*とVP8*に開裂する[29]。VP4はウイルスの病原性を決定する因子であり、またロタウイルスのP型を決定する因子でもある[30]。

VP6はカプシドの主成分で内殻を構成する[17]。抗原性が高く、ロタウイルスの種の同定に用いられる[5]。また、VP6はA群ロタウイルス感染における検査に使用される[31]。

VP7はウイルス粒子の外殻を形成する糖タンパク質である[17]。構造に関わる他、VP7はG型を決定し、VP4と共にロタウイルス感染に対する免疫に関係する[18]。

非構造タンパク質

NSP1は第5分節に由来する遺伝子産物で、非構造性のRNA結合タンパク質である[32]。また、NSP1はインターフェロンに誘導される応答を阻害し、ウイルスの感染から細胞を守る自然免疫系の反応を抑える。NSP1は、感染細胞におけるインターフェロン産生の増強と、隣接細胞によって分泌されたインターフェロンに対する応答に必要な重要なシグナル分子を、プロテオソームによって分解してしまう。分解の標的となる分子としては、インターフェロン遺伝子の転写に必要なIRF転写因子などがある[33]。

NSP2は細胞質内封入体に蓄積するRNA結合タンパク質で、ゲノム複製に必要な分子である[34][35]。

NSP3は感染細胞内でウイルスmRNAに結合しており、細胞のタンパク質合成を遮断する役割を持つ[36]。NSP3は宿主のmRNAからタンパク質を合成するために必要な2つの翻訳開始因子を不活化する。NSP3はまず、転写開始因子elF4FからポリA結合タンパク質 (PABP) を外してしまう。PABPは3' ポリA尾部を持つ転写産物からの効率的な翻訳に必要な因子で、宿主細胞の転写産物のほとんどに結合している。次にNSP3はelf2のリン酸化を促進することで、これを不活化する。ロタウイルスのmRNAはポリA尾部を欠いており、上記の2つの因子のいずれも翻訳に必要ではない[37]。

NSP4は下痢を引き起こすウイルス性のエンテロトキシンで、ウイルス性のエンテロトキシンとしては初めて発見されたものである[38]。

NSP5はA群ロタウイルスの第11分節にコードされる。感染細胞においてNSP5はヴィロプラズムに蓄積している[39]。

NSP6は核酸結合タンパク質で[40]第11分節にコードされており、位相の異なる (out-of-phase) オープンリーディングフレームから転写される[41]。

| RNA分節 (遺伝子) | 大きさ (塩基対) | タンパク質 | 分子量 kDa | 局在 | 粒子あたりのコピー数 | 機能 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3302 | VP1 | 125 | コアの頂点 | <25 | RNA依存性RNAポリメラーゼ |

| 2 | 2690 | VP2 | 102 | コアの内貼り | 120 | RNA複製酵素の活性化 |

| 3 | 2591 | VP3 | 88 | コアの頂点 | <25 | メチルトランスフェラーゼ、mRNAキャッピング酵素 |

| 4 | 2362 | VP4 | 87 | 表面のスパイク | 120 | 細胞への吸着、病原性 |

| 5 | 1611 | NSP1 | 59 | 非構造 | 0 | 5'RNAに結合、インターフェロン競合阻害 |

| 6 | 1356 | VP6 | 45 | カプシドの内殻 | 780 | 構造タンパク質で種特異的抗原 |

| 7 | 1104 | NSP3 | 37 | 非構造 | 0 | ウイルスmRNAの活性を増強し、細胞性のタンパク質合成を遮断 |

| 8 | 1059 | NSP2 | 35 | 非構造 | 0 | RNAのパッケージングに関わるNTPase |

| 9 | 1062 | VP71 VP72 | 38および34 | 表面 | 780 | 構造タンパク質、中和タンパク質 |

| 10 | 751 | NSP4 | 20 | 非構造 | 0 | エンテロトキシン |

| 11 | 667 | NSP5 NSP6 | 22 | 非構造 | 0 | ssRNAおよびdsRNAとの結合を担う、リン酸化を受ける |

この表はサルロタウイルスSA11株を許にしている[42][43][44]。RNAとタンパク質の割り当ては一部の株で異なる。

複製

ロタウイルスの複製は主に腸で行われ[45]、小腸の腸細胞の絨毛に感染、上皮に構造的、機能的変化をもたらす[46]。三重のタンパク質の被膜により胃の酸性環境や腸管の消化酵素に耐えることができる。

ロタウイルスは細胞へ受容体性エンドサイトーシスによって侵入、エンドソームと呼ばれる小胞を形成する。最外層のタンパク質(VP7とVP4)はエンドソームの膜を破壊し、カルシウム濃度に変化をさせる。これがVP7三量体の崩壊を起こし、VP2とVP6によってなるdsRNAを包む殻を露出させた二重膜粒子の形成につながる[47]。

11の二本鎖RNA分節が二層のタンパク質の殻に囲まれたまま、ウイルス性のRNA依存性RNAポリメラーゼによってウイルスのゲノムからmRNAが転写される。コアによって囲まれているため、ウイルスのRNAは、二本鎖RNAによって活性化する自然免疫反応であるRNA干渉を回避することができる。

感染時にロタウイルスはタンパク質の合成およびゲノム複製の両者のためにmRNAの合成を行う。ロタウイルスのタンパク質のほとんどはヴィロプラズムに集積し、RNAの複製と二重膜粒子の組み立てがこの場で行われる。ヴィロプラズムは核の周縁に感染後二時間で形成され始め、2つの非構造タンパク質、NSP5とNSP2によって構成されると考えられているウイルス工場である。RNA干渉によってNSP5を阻害するとロタウイルスの複製効率は急激に低下する。二重膜粒子は小胞体へ輸送され、VP7とVP4によって構成される三番目の殻、外膜を獲得する。娘ウイルスは細胞溶解を伴って放出される[29][48][49]。

感染経路

ロタウイルスは汚染された手や物との接触を通じて糞口経路によって伝播するが[50]、さらに空気感染の可能性もある[51]。ウイルス性の下痢は感染性が非常に高い。感染者の糞便は1グラムあたりで最大10兆以上のウイルス粒子を含み[5]、100以下のウイルス粒子でも感染が成立する[7]。

ロタウイルスは環境中でも安定である[10]。細菌や寄生虫の除去に十分なほど衛生状態が良好でもロタウイルスの感染を抑えるには不十分なようであり、衛生状態の高い国と低い国でもロタウイルス感染症の罹患率はほとんど等しい[51]。

発病機構

下痢はウイルスの活動によって発生する。吸収不良は腸細胞(小腸吸収上皮細胞とも)と呼ばれる腸管の細胞の破壊による。ロタウイルスの産生するタンパク質、NSP4はエンテロトキシンであり、このタンパク質は年齢やカルシウムイオン依存的に塩化物イオンの分泌を促進、ナトリウム-グルコース共輸送タンパク質による水の再吸収を阻害、刷子縁のジサッカリダーゼを阻害する効果を持ち、さらに腸神経系のカルシウム依存性分泌反射を活性化する可能性がある[38]。腸細胞は小腸にラクターゼを分泌する役割を持ち、ラクターゼの喪失による牛乳不耐性はロタウイルス感染の症状の1つであるが[52]、この症状は数週間に渡って継続する事がある[53]。牛乳をしばらく子どもの食事から除いた後、再び食事に加えるとしばしば軽度の下痢が再発する。これは腸管の細菌による二糖(ラクトース)の発酵が原因である[54]。

診断と検出

ロタウイルスの感染を診断するには通常重篤な下痢の原因となる胃腸炎の診断に続く。小児が胃腸炎によって病院で診察を受ける場合はほとんどの場合A群ロタウイルスの検査が行われる[55][56]。A群ロタウイルスの特異的診断は小児の便を試料としたELISA法によるウイルスの検出によってなされる。感度、特異性が高い、A群ロタウイルスの全血清型を検出できる認可済みの診断キットは複数の製品が市場に流通している[25]。他の検出法としては、電子顕微鏡によるウイルス粒子の確認や、PCRによる検出が研究目的の実験室で用いられる[57]。また、逆転写PCR (RT-PCR) 法を用いる事でヒトのロタウイルスの全ての種の全ての血清型を診断、同定できる[58]。

治療と予後

ロタウイルスの急性感染における治療は非特異的な対症療法であり、脱水の対策が最も重要となる[59]。無治療の場合、小児は重度の脱水を起こすと死に至る事もある[60]。下痢の重篤度に応じて経口補液を行い、補液時においては少量の塩分と糖分を含む十分な量の水を飲ませる[61]。2004年にはWHOとUNICEFが急性下痢の治療用に低浸透圧の経口補水液と亜鉛サプリメントの併用を推奨している[62]。感染した小児のおよそ50%が受診、そのうち約10%が脱水を理由に入院が必要となり[17]、点滴や経鼻胃管による補液、電解質や血糖値のモニタリングが行われる[55]。また、プロバイオティクスはロタウイルスによる下痢の持続期間を減少させることが示されており[63]、ヨーロッパ小児消化器病学会は「効果的な介入としてラクトバチルス・ラムノサスやサッカロマイセス・ブラウディなどのプロバイオティクス、ジオスメクタイト、ラセカドトリルの投与がある[64]」としている。ロタウイルスが他の合併症を招く事は稀であり、先進国では適切に治療されれば小児の予後は良好であるが[65]、発展途上国では年間数十万人がロタウイルス感染による下痢症で死亡し[17]、また、腸重積、肝炎、胆道閉鎖症、1型糖尿病、腎後性腎不全、脳炎、髄膜炎、脳症などさまざまな病態との関連が疑われる事もある[10][17][66]。

疫学

A群ロタウイルスはヒトのロタウイルス性胃腸炎の原因の90%を占め、世界的に常在している[67]。発展途上国では一年間にロタウイルスが数百万件の下痢症を引き起こしており、このうちのほぼ200万件の患者が入院する[68]。2013年には5歳未満の幼児、215,000人がロタウイルスにより死亡しており、その90%は発展途上国における死である[69]。5歳までにほぼ全ての幼児がロタウイルスに感染する[70]。ロタウイルスは乳幼児の重篤な下痢の主因であり、入院の原因の3分の1を占め[71]、5歳未満の乳幼児において下痢に起因する死の37%、全死因の5%をそれぞれ占める[72]。男児は女児に比べ、ロタウイルスにより入院する事が多いようである[73][74]。 ロタウイルスの感染は主に冷涼で乾燥した季節に発生する[75][76]。汚染食料に起因する感染事例数は定かでない[77]。

A群ロタウイルスによる下痢症は病院にいる乳児、デイケアセンターを利用する幼児、老人ホームに住む高齢者等の間で流行する[78]。また、コロラドでは1981年に汚染された水道水が原因になって流行したこともある[79]。 2005年にはニカラグアで記録に残る上では最大級の流行が発生した。この前例のない大規模な流行はA群ロタウイルスのゲノムに生じた変異と関連しており、ウイルスは変異を起こす事で住民の間で共有されていた免疫を回避する事ができた可能性がある[80]。同等の大流行は1977年にブラジルでも発生している[81]。

成人下痢症ウイルス(ADRV株)とも呼ばれるB群ロタウイルスは中国で感染者が全世代に渡る、数千人規模の大流行を起こしてきた。この一連の流行は飲料用の水が下水によって汚染されたために発生している[82][83]。1998年にはインドでもB群ロタウイルス感染症が発生しており、病原ウイルスの株名がCAL株と命名された。流行を起こしてきたADRV株と異なり、CAL株は常在性であるようである[84][85]。これまでのB群ロタウイルスの流行は特定の地域に限局にしており、例えばアメリカ人はB群ロタウイルスに対して免疫を持たないことが血清調査から示されている[86]。

C群ロタウイルスは散発的に小児の下痢を引き起こしており、小規模の流行が家庭内で生じた事もある[87]。

予防

ロタウイルスは感染性が強く、また抗生物質やその他の治療薬は効果がない。衛生状態の改善ではロタウイルス感染症の蔓延を防ぐことができず、一方で経口補水を行なってもなお入院率が高いため、ロタウイルスへの主な医療介入には予防接種が行われる[88]。世界的に認可されているA群ロタウイルスに対してのワクチンとして、ロタリックス(Rotarix; グラクソ・スミスクライン)[89]およびロタテック (RotaTeq; MSD) [90]が存在し、いずれも小児に対して安全で効果的である[91]。重症ロタウイルス下痢症乳児の大幅な減少成果を認め[92]、共にコクランのレビューで発症阻止能が認められている[93]。1990年代に使用されていたワクチン (RotaShield) の副反応として腸重積が多発したことが報告されていたが[1]、2006年頃以降市場に出ているワクチンと腸重積との関連性は認められていない。いずれも経口ワクチンで弱毒生ウイルスを含む[91]。2014年にインドで認可されたROTAVAC、2007年にベトナムで認可されたMotavin-M1、2000年に中国で認可されたLanzhou Lambの3つは特定の国の市場においてのみ認可されている[94]。2017年現在、二つの有効なワクチンの保存は冷蔵できる環境が必要である。このことは、コストが大きくなるとともに接種可能な場所や対象は制約を受ける。このため、新たなワクチンの開発も試みられている[95]。また、他にも複数のロタウイルスワクチンが開発中である[96]。

2009年に世界保健機構(WHO)は各国における予防接種プログラムへのロタウイルスワクチン導入を推奨した[97]。この推奨策を実施した国ではロタウイルス感染症の発生率と重症度が明らかに減衰している[98][91][99]。予防接種プログラムにロタウイルスワクチンを導入した国において行われた臨床治験のデータをまとめた2014年のレビューはロタウイルスワクチンがロタウイルスに起因する入院を49-92%減少させ、さらに全下痢症の入院患者数を17-55%減少させることを明らかにした[100]。 2006年にロタウイルスワクチンを世界で初めて導入した国の1つであるメキシコでは、ロタウイルス性の下痢症による2歳以下の死亡率が2009年のシーズンには65%以上減少した[101]。ニカラグアは2006年に発展途上国として初めてロタウイルスワクチンを導入し、ロタウイルスの感染を40%まで減少させ、救急救命室の利用を半減させた[102]。アメリカ合衆国ではロタウイルスワクチンの接種が2006年に開始され、ロタウイルスの検出数が86%低下している[103]。ワクチンは市中の感染数を減少させることで、免疫を受けていない小児の疾患をも予防するかもしれない[104]。ロタウイルスによる死はほとんどがアフリカやアジアの発展途上国で発生するが、これらの国々ではRotarixとRotaTeqに関する多数の臨床試験が行われた他、近年はワクチン導入後の影響を評価する調査が実施され、ワクチンの導入によって乳児の重症例が劇的に減少することが示された[99][105][106][107]。2013年にはイギリスで2-3ヶ月の全ての乳児に対しワクチンが提供された。これはロタウイルス感染の重症例を半減させ、入院例を70%減少させることを期待して行われている[108]。ヨーロッパではワクチンの導入によってロタウイルス感染による入院例が65%から84%減少した[109]。 ロタウイルスワクチンは100カ国以上の国で認可されており、さらに80カ国以上の国が予防接種プログラムに組み入れている。また、そのうちおよそ半数の国はGAVIアライアンスによる援助を受けている[110]。ロタウイルスワクチンを全ての国(特にロタウイルスによる死のほとんどが発生するアフリカやアジアの低所得ないし中所得国)に導入させるため、PATH、WHO、アメリカ疾病予防管理センターおよびGAVIアライアンスは研究機関や政府と協力し、普及活動に努めている[111]。

動物のロタウイルス感染

ロタウイルスは多くの種の動物の幼齢個体に感染し、野生動物にとっても飼育動物にとってもロタウイルスは世界的に下痢の主要な病原体である[112]。仔牛や仔豚をはじめとした家畜の病原体として、高い罹患率と致死率を持つロタウイルスは治療に係る経費によって農場経営者に対し経済的損失を生じさせる[113]。また、動物のロタウイルスはヒトのロタウイルスと遺伝子を交換することができる[113]。動物のロタウイルスがヒトに感染することがあり、これは直接動物のウイルスがヒトに感染する場合と、動物のロタウイルスのRNA分節の一部が遺伝子再集合を経てヒトの株に取り込まれる場合とがある[114][115]。

脚注

- ^ a b ロタウイルスの最近の話題 モダンメディア 2006年12月号(第52巻12号)

- ^ “Rotavirus vaccine, live, oral, tetravalent (RotaShield)”. Pediatr. Nurs. 25 (2): 203–4, 207. (1999). PMID 10532018.

- ^ “Rotavirus”. Baillieres Clin. Gastroenterol. 4 (3): 609–25. (1990). doi:10.1016/0950-3528(90)90052-I. PMID 1962726.

- ^ “Rotavirus vaccines: current prospects and future challenges”. Lancet 368 (9532): 323–32. (July 2006). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68815-6. PMID 16860702.

- ^ a b c Bishop RF (1996). “Natural history of human rotavirus infection”. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 12: 119–28. PMID 9015109.

- ^ Ward R (March 2009). “Mechanisms of protection against rotavirus infection and disease”. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 28 (3 Suppl): S57–9. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967c16. PMID 19252425.

- ^ a b “Rotavirus vaccines: opportunities and challenges”. Human Vaccines 5 (2): 57–69. (February 2009). doi:10.4161/hv.5.2.6924. PMID 18838873.

- ^ Hrdy DB (1987). “Epidemiology of rotaviral infection in adults”. Rev. Infect. Dis. 9 (3): 461–9. doi:10.1093/clinids/9.3.461. PMID 3037675.

- ^ Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV)

- ^ a b c “ロタウイルス感染性胃腸炎とは”. 国立感染症研究所. 2017年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Porcine rotavirus closely related to novel group of human rotaviruses”. Emerging Infectious Diseases 17 (8): 1491–3. (2011). doi:10.3201/eid1708.101466. PMC 3381553. PMID 21801631.

- ^ “Widespread rotavirus H in commercially raised pigs, United States”. Emerging Infectious Diseases 20 (7): 1195–8. (2014). doi:10.3201/eid2007.140034. PMC 4073875. PMID 24960190.

- ^ O'Ryan M (March 2009). “The ever-changing landscape of rotavirus serotypes”. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 28 (3 Suppl): S60–2. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967c29. PMID 19252426.

- ^ Patton JT (January 2012). “Rotavirus diversity and evolution in the post-vaccine world”. Discovery Medicine 13 (68): 85–97. PMC 3738915. PMID 22284787.

- ^ “Rotavirus types in Europe and their significance for vaccination”. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25 (1 Suppl.): S30–41. (2006). doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000197707.70835.f3. PMID 16397427.

- ^ Desselberger, U.; Gray, James (2000). Desselberger, U.; Gray, James. eds. Rotaviruses: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-89603-736-3

- ^ a b c d e f g 平松啓一・中込治 編『標準微生物学』(第10版)医学書院、2009年、426-434頁。ISBN 978-4-260-00638-5。

- ^ a b “Rotavirus proteins: structure and assembly”. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol.. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 309: 189–219. (2006). doi:10.1007/3-540-30773-7_7. ISBN 978-3-540-30772-3. PMID 16913048.

- ^ “Structure of rotavirus”. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 185: 9–29. (1994). PMID 8050286.

- ^ Kirkwood CD (September 2010). “Genetic and antigenic diversity of human rotaviruses: potential impact on vaccination programs”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 202 (Suppl): S43–8. doi:10.1086/653548. PMID 20684716.

- ^ Patton JT (1995). “Structure and function of the rotavirus RNA-binding proteins” (PDF). J. Gen. Virol. 76 (11): 2633–44. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-76-11-2633. PMID 7595370.

- ^ Patton JT (2001). “Rotavirus RNA replication and gene expression”. Novartis Found. Symp.. Novartis Foundation Symposia 238: 64–77; discussion 77–81. doi:10.1002/0470846534.ch5. ISBN 9780470846537. PMID 11444036.

- ^ “Bioinformatic prediction of polymerase elements in the rotavirus VP1 protein”. Biol. Res. 39 (4): 649–59. (2006). doi:10.4067/S0716-97602006000500008. PMID 17657346.

- ^ “Interaction of rotavirus polymerase VP1 with nonstructural protein NSP5 is stronger than that with NSP2”. J. Virol. 81 (5): 2128–37. (2007). doi:10.1128/JVI.01494-06. PMC 1865955. PMID 17182692.

- ^ a b Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology. Boston: Academic Press. (2009). p. 277. ISBN 0-12-375147-0

- ^ Cowling VH (January 2010). “Regulation of mRNA cap methylation”. Biochem. J. 425 (2): 295–302. doi:10.1042/BJ20091352. PMC 2825737. PMID 20025612.

- ^ “Rotavirus spike protein VP4 binds to and remodels actin bundles of the epithelial brush border into actin bodies”. J. Virol. 80 (8): 3947–56. (2006). doi:10.1128/JVI.80.8.3947-3956.2006. PMC 1440440. PMID 16571811.

- ^ “Molecular biology of rotavirus cell entry”. Arch. Med. Res. 33 (4): 356–61. (2002). doi:10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00374-0. PMID 12234525.

- ^ a b “Emerging themes in rotavirus cell entry, genome organization, transcription and replication”. Virus Research 101 (1): 67–81. (April 2004). doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.007. PMID 15010218.

- ^ “Characterization of neutralization specificities of outer capsid spike protein VP4 of selected murine, lapine, and human rotavirus strains”. Virology 299 (1): 64–71. (2002). doi:10.1006/viro.2002.1474. PMID 12167342.

- ^ “Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays based on polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies for rotavirus detection” (PDF). J. Clin. Microbiol. 19 (2): 248–54. (1 February 1984). PMC 271031. PMID 6321549.

- ^ “Comparative analysis of the rotavirus NS53 gene: conservation of basic and cysteine-rich regions in the protein and possible stem-loop structures in the RNA”. Virology 196 (1): 372–8. (1993). doi:10.1006/viro.1993.1492. PMID 8395125.

- ^ “The Rotavirus Interferon Antagonist NSP1: Many Targets, Many Questions”. Journal of Virology 90 (11): 5212–5. (2016). doi:10.1128/JVI.03068-15. PMID 27009959.

- ^ “The rotavirus RNA-binding protein NS35 (NSP2) forms 10S multimers and interacts with the viral RNA polymerase”. Virology 202 (2): 803–13. (1994). doi:10.1006/viro.1994.1402. PMID 8030243.

- ^ “Nonstructural proteins involved in genome packaging and replication of rotaviruses and other members of the Reoviridae”. Virus Res. 101 (1): 57–66. (2004). doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.006. PMID 15010217.

- ^ Poncet D, Aponte C, Cohen J (1 June 1993). “Rotavirus protein NSP3 (NS34) is bound to the 3' end consensus sequence of viral mRNAs in infected cells” (PDF). J. Virol. 67 (6): 3159–65. PMC 237654. PMID 8388495.

- ^ López, S; Arias, CF (August 2012). “Rotavirus-host cell interactions: an arms race.”. Current Opinion in Virology 2 (4): 389–98. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2012.05.001. PMID 22658208.

- ^ a b “Rotavirus vaccines and pathogenesis: 2008”. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 25 (1): 36–43. (January 2009). doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328317c897. PMC 2673536. PMID 19114772.

- ^ “Phosphorylation generates different forms of rotavirus NSP5”. J. Gen. Virol. 77 (9): 2059–65. (1996). doi:10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2059. PMID 8811003.

- ^ “Characterization of the NSP6 protein product of rotavirus gene 11”. Virus Res. 130 (1–2): 193–201. (2007). doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.06.011. PMID 17658646.

- ^ “Nucleotide sequence analysis of rotavirus gene 11 from two tissue culture-adapted ATCC strains, RRV and Wa”. Virus Genes 23 (3): 321–9. (2001). doi:10.1023/A:1012577407824. PMID 11778700.

- ^ Desselberger U. Rotavirus: basic facts. In Rotaviruses Methods and Protocols. Ed. Gray, J. and Desselberger U. Humana Press, 2000, pp. 1–8. ISBN 0-89603-736-3

- ^ Patton JT. Rotavirus RNA replication and gene expression. In Novartis Foundation. Gastroenteritis Viruses, Humana Press, 2001, pp. 64–81. ISBN 0-471-49663-4

- ^ Claude M. Fauquet; J. Maniloff; Desselberger, U. (2005). Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses: 8th report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 489. ISBN 0-12-249951-4

- ^ “Rotaviruses: from pathogenesis to vaccination”. Gastroenterology 136 (6): 1939–51. (May 2009). doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.076. PMC 3690811. PMID 19457420.

- ^ “Rotavirus pathology and pathophysiology”. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 185: 255–83. (1994). PMID 8050281.

- ^ “Rotavirus cell entry”. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 343: 121–48. (2010). doi:10.1007/82_2010_34. ISBN 978-3-642-13331-2. PMID 20397068.

- ^ “Replication and transcription of the rotavirus genome”. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10 (30): 3769–77. (2004). doi:10.2174/1381612043382620. PMID 15579070.

- ^ “Molecular biology of rotavirus entry and replication”. TheScientificWorldJournal 9: 1476–97. (2009). doi:10.1100/tsw.2009.158. PMID 20024520.

- ^ “Prevalence of rotavirus on high-risk fomites in day-care facilities”. Pediatrics 92 (2): 202–5. (1993). PMID 8393172.

- ^ a b Dennehy PH (2000). “Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home”. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19 (10 Suppl): S103–5. doi:10.1097/00006454-200010001-00003. PMID 11052397.

- ^ Farnworth ER (June 2008). “The evidence to support health claims for probiotics”. The Journal of Nutrition 138 (6): 1250S–4S. PMID 18492865.

- ^ “Health aspects of probiotics”. IDrugs 6 (6): 573–80. (2003). PMID 12811680.

- ^ Arya SC (1984). “Rotaviral infection and intestinal lactase level”. J. Infect. Dis. 150 (5): 791. doi:10.1093/infdis/150.5.791. PMID 6436397.

- ^ a b “Routine laboratory testing data for surveillance of rotavirus hospitalizations to evaluate the impact of vaccination”. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 26 (10): 914–9. (October 2007). doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52fd. PMID 17901797.

- ^ The Pediatric ROTavirus European CommitTee (PROTECT) (2006). “The paediatric burden of rotavirus disease in Europe”. Epidemiol. Infect. 134 (5): 908–16. doi:10.1017/S0950268806006091. PMC 2870494. PMID 16650331.

- ^ Goode, Jamie; Chadwick, Derek (2001). Gastroenteritis viruses. New York: Wiley. p. 14. ISBN 0-471-49663-4

- ^ “Rotavirus typing methods and algorithms”. Reviews in Medical Virology 14 (2): 71–82. (2004). doi:10.1002/rmv.411. PMID 15027000.

- ^ Diggle L (2007). “Rotavirus diarrhea and future prospects for prevention”. Br. J. Nurs. 16 (16): 970–4. PMID 18026034.

- ^ “Treatment of infectious diarrhea in children”. Paediatr. Drugs 5 (3): 151–65. (2003). doi:10.2165/00128072-200305030-00002. PMID 12608880.

- ^ Sachdev HP (1996). “Oral rehydration therapy”. Journal of the Indian Medical Association 94 (8): 298–305. PMID 8855579.

- ^ World Health Organization, UNICEF. “Joint Statement: Clinical Management of Acute Diarrhoea”. 2012年5月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Efficacy of probiotic use in acute rotavirus diarrhea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. Caspian J Intern Med 6 (4): 187–95. (2015).

- ^ Guarino A1, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, Lo Vecchio A, Shamir R, Szajewska H (2014). “European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: update 2014.”. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 59 (1): 132–52. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000000375.

- ^ Ramig RF (August 2007). “Systemic rotavirus infection”. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 5 (4): 591–612. doi:10.1586/14787210.5.4.591. PMID 17678424.

- ^ ロタウイルス感染に関連した急性脳症の 1例 日大医学雑誌 Vol.67 (2008) No.5 P304-308

- ^ “Rotavirus gastroenteritis”. Adv. Ther. 22 (5): 476–87. (2005). doi:10.1007/BF02849868. PMID 16418157.

- ^ “Use of formative research in developing a knowledge translation approach to rotavirus vaccine introduction in developing countries”. BMC Public Health 7: 281. (2007). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-281. PMC 2173895. PMID 17919334.

- ^ Tate, Jacqueline E.; Burton, Anthony H.; Boschi-Pinto, Cynthia; Parashar, Umesh D. (2016). “Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000–2013”. Clinical Infectious Diseases 62 (Suppl 2): S96-S105.

- ^ “Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea”. Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (2): 304–6. (2006). doi:10.3201/eid1202.050006. PMC 3373114. PMID 16494759.

- ^ Leshem, Eyal; Moritz, Rebecca E.; Curns, Aaron T.; et al. (2014). “Rotavirus Vaccines and Health Care Utilization for Diarrhea in the United States (2007–2011)”. Pediatrics 134 (1): 15–23.

- ^ “2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. Lancet Infect Dis 12 (2): 136–141. (February 2012). doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5. PMID 22030330.

- ^ “Economics of rotavirus gastroenteritis and vaccination in Europe: what makes sense?”. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25 (1 Suppl): S48–55. (2006). doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000197566.47750.3d. PMID 16397429.

- ^ “Hospital admissions attributable to rotavirus infection in England and Wales”. J. Infect. Dis. 174 (Suppl 1): S12–8. (1996). doi:10.1093/infdis/174.Supplement_1.S12. PMID 8752285.

- ^ “Temperature-dependent transmission of rotavirus in Great Britain and The Netherlands”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277 (1683): 933–42. (March 2010). doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1755. PMC 2842727. PMID 19939844.

- ^ “Seasonality of rotavirus disease in the tropics: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. International Journal of Epidemiology 38 (6): 1487–96. (December 2009). doi:10.1093/ije/dyn260. PMC 2800782. PMID 19056806.

- ^ “Seasonality and diversity of Group A rotaviruses in Europe”. Acta Paediatrica Supplement 88 (426): 14–9. (1999). doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14320.x. PMID 10088906.

- ^ “Rotavirus infection in adults”. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 4 (2): 91–9. (February 2004). doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00928-4. PMID 14871633.

- ^ “A community waterborne gastroenteritis outbreak: evidence for rotavirus as the agent”. American Journal of Public Health 74 (3): 263–5. (1984). doi:10.2105/AJPH.74.3.263. PMC 1651463. PMID 6320684.

- ^ “Mutated G4P[8 rotavirus associated with a nationwide outbreak of gastroenteritis in Nicaragua in 2005”]. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 (3): 990–7. (2007). doi:10.1128/JCM.01992-06. PMC 1829148. PMID 17229854.

- ^ “An outbreak of rotavirus diarrhea among a non-immune, isolated South American Indian community”. Am. J. Epidemiol. 113 (6): 703–10. (1981). PMID 6263087.

- ^ “Waterborne outbreak of rotavirus diarrhea in adults in China caused by a novel rotavirus”. Lancet 1 (8387): 1139–42. (1984). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91391-6. PMID 6144874.

- ^ “Investigation of an outbreak of adult diarrhea rotavirus in China”. J. Infect. Dis. 160 (6): 948–53. (1989). doi:10.1093/infdis/160.6.948. PMID 2555422.

- ^ “Group B rotaviruses similar to strain CAL-1, have been circulating in Western India since 1993”. Epidemiol. Infect. 132 (4): 745–9. (2004). doi:10.1017/S0950268804002171. PMC 2870156. PMID 15310177.

- ^ “Genetic analysis of group B human rotaviruses detected in Bangladesh in 2000 and 2001”. J. Med. Virol. 72 (1): 149–55. (2004). doi:10.1002/jmv.10546. PMID 14635024.